Mihai Eminescu

Mihai Eminescu | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Mihai Eminescu. Photograph taken by Jan Tomas in Prague, 1869. | |

| Born | Mihail Eminovici 15 January 1850 Botoșani, Principality of Moldavia |

| Died | 15 June 1889 (aged 39) Bucharest, Kingdom of Romania |

| Resting place | Bellu Cemetery, Bucharest |

| Occupation | |

| Language | Romanian |

| Citizenship | |

| Education | |

| Genres | Poetry, short story |

| Subjects | Condition of genius, death, love, history, nature |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Years active | 1866–1889 |

| Notable works | Luceafărul, Scrisoarea I |

| Partner | Veronica Micle |

| Relatives | Gheorghe Eminovici (father) Raluca Iurașcu (mother)[1] Six brothers

Four sisters

|

| Signature | |

| |

Mihai Eminescu (Romanian pronunciation: [miˈhaj emiˈnesku] ; born Mihail Eminovici; 15 January 1850 – 15 June 1889) was a Romanian Romantic poet from Moldavia, novelist, and journalist, generally regarded as the most famous and influential Romanian poet. Eminescu was an active member of the Junimea literary society and worked as an editor for the newspaper Timpul ("The Time"), the official newspaper of the Conservative Party (1880–1918).[2] His poetry was first published when he was 16 and he went to Vienna, Austria to study when he was 19. The poet's manuscripts, containing 46 volumes and approximately 14,000 pages, were offered by Titu Maiorescu as a gift to the Romanian Academy during the meeting that was held on 25 January 1902.[3] Notable works include Luceafărul (The Vesper/The Evening Star/The Lucifer/The Daystar), Odă în metru antic (Ode in Ancient Meter), and the five Letters (Epistles/Satires). In his poems, he frequently used metaphysical, mythological and historical subjects.

His father was Gheorghe Eminovici, an aristocrat from Bukovina, which was then part of the Austrian Empire (while his grandfather came from Banat). He crossed the border into Moldavia, settling in Ipotești, near the town of Botoșani. He married Raluca Iurașcu, an heiress of an old noble family. In a Junimea register, Eminescu wrote down his birth date as 22 December 1849, while in the documents of Cernăuți Gymnasium, where Eminescu studied, his birth date is 15 January 1850. Nevertheless, Titu Maiorescu, in his work Eminescu and His Poems (1889), quoted N. D. Giurescu's research and adopted his conclusion regarding the date and place of Mihai Eminescu's birth, as being 15 January 1850, in Botoșani. This date resulted from several sources, among which there was a file of notes on christenings from the archives of the Uspenia (Princely) Church of Botoșani; inside this file, the date of birth was "15 January 1850" and the date of christening was the 21st of the same month. The date of his birth was confirmed by the poet's elder sister, Aglae Drogli, who affirmed that the place of birth was the village of Ipotești, Botoșani County.[4]

Life

Family

The most accepted theory is that Mihail's paternal ancestors came from a Romanian family from Banat. In 1675, a child was born with the name Iminul.[5] The son of Iminul was Iovul lui Iminul, born in 1705, who was ordained a priest under the Serbianized name of Iovul Iminovici, in accordance with the use of Church Slavonic of the Metropolitanate of Karlovci.[6][7]

The priest Iovul Iminovici left Banat for Blaj between 1738-1740, attracted by civil liberties, agricultural land for a fee and free education in the Romanian language for his children, but on the condition of becoming an Eastern-Rite Catholic. Iovul Iminovici had two sons, Iosif and Petrea Iminovici. Petrea Eminovici, the poet's great-grandfather, was probably born in 1735 and from his marriage with Agafia Şerban (born in 1736), several descendants appeared, known with certainty being only the existence of their middle child, Vasile, the grandfather of the poet.[8] Vasile Iminovici, born in 1778, attended the normal school in Blaj and married Ioana Sărghei. After a while, the spouses Petrea and Agafia divorced. Petrea died in Blaj in 1811, and Agafia accompanied the family of her son, Vasile, to Bukovina. Agafia died in 1818 in Călinești, Suceava.[9]

Vasile Iminovici, attracted by the economic and social conditions settled in Bukovina, moved with his family to Călinești in 1804, where he received a position as a church teacher as well as land. He had four daughters and three sons. Vasile Iminovici died in 1844. The eldest of his sons, Gheorghe, born in 1812 was the father of Mihai Eminescu. [10][11][12] Gheorghe Eminovici was in the service of the boyar Ioan Ienacaki Cârstea from Costâna, Suceava, then - writer for baron Jean Mustață from Bukovina, and later in the service of the boyar Alexandru Balș from Moldova. After the death of Alexandru Balș, his son, Costache, appointed Gheorghe Eminovici as administrator of the Dumbrăveni estate. Later, Gheorghe Eminovici obtained the title of sluger from Costache Balș.[13]

Another theory from the historian George Călinescu says that Mihai's paternal great-grandfather might have been a cavalry officer from the army of Charles XII of Sweden, who settled in Moldavia after the battle of Poltava (1709).[14]

The ancestors from the mother's side, the Jurăscești family, came from Hotin (present day Ukraine, near the border with Romania). The boyar Vasile Jurașcu from Joldești, Botoșani married Paraschiva, the daughter of Donțu, a Cossack, who had settled on the banks of the Siret, not far from the village of Sarafinești, Botoșani. Donțu married the daughter of the peasant Ion Brehuescu, Catrina. [15] Raluca, the poet's mother, was the fourth daughter of Vasile and Paraschiva Jurașcu. [16]

Gheorghe Eminovici married Raluca Jurașcu in 1840, receiving a substantial dowry, [17][18] and in 1841 he received the title of căminar (a type of boyar) from the voivode Mihail Grigore Sturza.[19]

Early years

Mihail (as he appears in baptismal records) or Mihai (the more common form of the name that he used) was born in Botoșani, Moldavia. Mihai Eminescu was the seventh of the eleven children of Gheorghe Eminovici and Raluca Jurașcu.[20] He spent his early childhood in Botoșani and Ipotești, in his parents family home. From 1858 to 1866 he attended school in Cernăuți. He finished 4th grade as the 5th of 82 students, after which he attended two years of gymnasium.

The first evidence of Eminescu as a writer is in 1866. In January of that year Romanian teacher Aron Pumnul died and his students in Cernăuţi published a pamphlet, Lăcrămioarele învățăceilor gimnaziaști (The Tears of the Gymnasium Students) in which a poem entitled La mormântul lui Aron Pumnul (At the Grave of Aron Pumnul) appears, signed "M. Eminovici". On 25 February his poem De-aș avea (If I Had) was published in Iosif Vulcan's literary magazine Familia in Pest. This began a steady series of published poems (and the occasional translation from German). Also, it was Iosif Vulcan, who disliked the Slavic source suffix "-ici" of the young poet's last name, that chose for him the more apparent Romanian "nom de plume" Mihai Eminescu.

In 1867, he joined Iorgu Caragiale's troupe as a clerk and prompter; the next year he transferred to Mihai Pascaly's troupe. Both of these were among the leading Romanian theatrical troupes of their day, the latter including Matei Millo and Fanny Tardini-Vlădicescu. He soon settled in Bucharest, where at the end of November he became a clerk and copyist for the National Theater. Throughout this period, he continued to write and publish poems. He also paid his rent by translating hundreds of pages of a book by Heinrich Theodor Rötscher, although this never resulted in a completed work. Also at this time he began his novel Geniu pustiu (Wasted Genius), published posthumously in 1904 in an unfinished form.

On 1 April 1869, he was one of the co-founders of the "Orient" literary circle, whose interests included the gathering of Romanian folklore and documents relating to Romanian literary history. On 29 June, various members of the "Orient" group were commissioned to go to different provinces. Eminescu was assigned Moldavia. That summer, he quite by chance ran into his brother Iorgu, a military officer, in Cișmigiu Gardens, but firmly rebuffed Iorgu's attempt to get him to renew his ties to his family.

Still in the summer of 1869, he left Pascaly's troupe and traveled to Cernăuţi and Iaşi. He renewed ties to his family; his father promised him a regular allowance to pursue studies in Vienna in the fall. As always, he continued to write and publish poetry; notably, on the occasion of the death of the former ruler of Wallachia, Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei, he published a leaflet, La moartea principelui Știrbei ("On the Death of Prince Știrbei").

1870s

From October 1869 to 1872 Eminescu studied at the University of Vienna. Not fulfilling the requirements to become a university student (as he did not have a baccalaureate degree), he attended lectures as a so-called "extraordinary auditor" at the Faculty of Philosophy and Law. He was active in student life, befriended Ioan Slavici, and came to know Vienna through Veronica Micle; he became a contributor to Convorbiri Literare (Literary Conversations), edited by Junimea (The Youth). The leaders of this cultural organisation, Petre P. Carp, Vasile Pogor, Theodor Rosetti, Iacob Negruzzi and Titu Maiorescu, exercised their political and cultural influence over Eminescu for the rest of his life. Impressed by one of Eminescu's poems, Venere şi Madonă (Venus and Madonna), Iacob Negruzzi, the editor of Convorbiri Literare, traveled to Vienna to meet him. Negruzzi would later write how he could pick Eminescu out of a crowd of young people in a Viennese café by his "romantic" appearance: long hair and gaze lost in thoughts.

In 1870 Eminescu wrote three articles under the pseudonym "Varro" in Federaţiunea in Pest, on the situation of Romanians and other minorities in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He then became a journalist for the newspaper Albina (The Bee) in Pest. From 1872 to 1874 he continued as a student in Berlin, thanks to a stipend offered by Junimea.

From 1874 to 1877, he worked as director of the Central Library in Iași, substitute teacher, school inspector for the counties of Iași and Vaslui, and editor of the newspaper Curierul de Iași (The Courier of Iaşi), all thanks to his friendship with Titu Maiorescu, the leader of Junimea and rector of the University of Iași. He continued to publish in Convorbiri Literare. He also was a good friend of Ion Creangă, a writer, whom he convinced to become a writer and introduced to the Junimea literary club.

In 1877 he moved to Bucharest, where until 1883 he was first journalist, then (1880) editor-in-chief of the newspaper Timpul (The Time). During this time he wrote Scrisorile, Luceafărul, Odă în metru antic etc. Most of his notable editorial pieces belong to this period, when Romania was fighting the Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 and throughout the diplomatic race that eventually brought about the international recognition of Romanian independence, but under the condition of bestowing Romanian citizenship to all subjects of Jewish faith. Eminescu opposed this and another clause of the Treaty of Berlin: Romania's having to give southern Bessarabia to Russia in exchange for Northern Dobruja, a former Ottoman province on the Black Sea.

Later life and death

The 1880s were a time of crisis and deterioration in the poet's life, culminating with his death in 1889. The details of this are still debated.

From 1883 – when Eminescu's personal crisis and his more problematic health issues became evident – until 1886, the poet was treated in Austria and Italy, by specialists that managed to get him on his feet, as testified by his good friend, writer Ioan Slavici.[21] In 1886, Eminescu suffered a nervous breakdown and was treated by Romanian doctors, in particular Julian Bogdan and Panait Zosin. Immediately diagnosed with syphilis, after being hospitalized in a nervous diseases hospice within the Neamț Monastery,[22] the poet was treated with mercury. Firstly, massages in Botoșani, applied by Dr. Itszak, and then in Bucharest at Dr. Alexandru A. Suțu's sanatorium, where between February–June 1889 he was injected with mercuric chloride.[23] Professor Doctor Irinel Popescu, corresponding member of the Romanian Academy and president of the Academy of Medical Sciences of Romania, states that Eminescu died because of mercury poisoning. He also says that the poet was "treated" by a group of incompetent doctors and held in misery, which also shortened his life.[24] Mercury was prohibited as treatment of syphilis in Western Europe in the 19th century, because of its adverse effects.

Mihai Eminescu died at 4 am, on 15 June 1889 at the Caritas Institute, a sanatorium run by Dr. Suțu and located on Plantelor Street Sector 2, Bucharest.[23] Eminescu's last wish was a glass of milk, which the attending doctor slipped through the metallic peephole of the "cell" where he spent the last hours of his life. In response to this favor he was said to have whispered, "I'm crumbled". The next day, on 16 June 1889 he was officially declared deceased and legal papers to that effect were prepared by doctors Suțu and Petrescu, who submitted the official report. This paperwork is seen as ambiguous, because the poet's cause of death is not clearly stated and there was no indication of any other underlying condition that may have so suddenly resulted in his death.[25] In fact both the poet's medical file and autopsy report indicate symptoms of a mental and not physical disorder. Moreover, at the autopsy performed by Dr. Tomescu and then by Dr. Marinescu from the laboratory at Babeș-Bolyai University, the brain could not be studied, because a nurse inadvertently forgot it on an open window, where it quickly decomposed.[25]

One of the first hypotheses that disagreed with the post mortem findings for Eminescu's cause of death was printed on 28 June 1926 in an article from the newspaper Universul. This article forwards the hypothesis that Eminescu died after another patient, Petre Poenaru, former headmaster in Craiova,[23] hit him in the head with a board.[26]

Dr. Vineș, the physician assigned to Eminescu at Caritas argued at that time that the poet's death was the result of an infection secondary to his head injury. Specifically, he says that the head wound was infected, turning into an erysipelas, which then spread to the face, neck, upper limbs, thorax, and abdomen.[25] In the same report, cited by Nicolae Georgescu in his work, Eminescu târziu, Vineș states that "Eminescu's death was not due to head trauma occurred 25 days earlier and which had healed completely, but was the consequence of an older endocarditis (diagnosed by late professor N. Tomescu)".[27]

Contemporary specialists, primarily physicians who have dealt with the Eminescu case, reject both hypotheses on the cause of death of the poet. According to them, the poet died of cardio-respiratory arrest caused by mercury poisoning.[28] Eminescu was wrongly diagnosed and treated, aiming his removal from public life, as some eminescologists claim.[22] Eminescu was diagnosed since 1886 by Dr. Julian Bogdan from Iași as syphilitic, paralytic and on the verge of dementia due to alcohol abuse and syphilitic gummas emerged on the brain. The same diagnosis is given by Dr. Panait Zosin, who consulted Eminescu on 6 November 1886 and wrote that patient Eminescu suffered from a "mental alienation", caused by the emergence of syphilis and worsened by alcoholism. Further research showed that the poet was not suffering from syphilis.[21]

Works

Nicolae Iorga, the Romanian historian, considers Eminescu the godfather of the modern Romanian language, in the same way that Shakespeare is seen to have directly influenced the English language. He is unanimously celebrated as the greatest and most representative Romanian poet.

Poems and Prose of Mihai Eminescu (editor: Kurt W. Treptow, publisher: The Center for Romanian Studies, Iași, Oxford, and Portland, 2000, ISBN 973-9432-10-7) contains a selection of English-language renditions of Eminescu's poems and prose.

Poetry

His poems span a large range of themes, from nature and love to hate and social commentary. His childhood years were evoked in his later poetry with deep nostalgia.

Eminescu's poems have been translated in over 60 languages. His life, work and poetry strongly influenced the Romanian culture and his poems are widely studied in Romanian public schools.

His most notable poems are:[29]

- De-aș avea, first poem of Mihai Eminescu

- Ce-ți doresc eu ție, dulce Românie

- Somnoroase păsărele

- Pe lângă plopii fără soț

- Doina (the name is a traditional type of Romanian song), 1884

- Lacul (The Lake), 1876

- Luceafărul (The Vesper), 1883

- Floare albastră (Blue Flower), 1884

- Dorința (Desire), 1884

- Sara pe deal (Evening on the Hill), 1885

- O, rămai (Oh, Linger On), 1884

- Epigonii (Epigones), 1884

- Scrisori (Letters or "Epistles-Satires")

- Și dacă (And if...), 1883

- Odă în metru antic (Ode in Ancient Meter), 1883

- Mai am un singur dor (I Have Yet One Desire), 1883

- Glossă (Gloss), 1883

- La Steaua (To The Star), 1886

- Memento mori, 1872

- Povestea magului călător în stele

Prose

- Sarmanul Dionis (Poor Dionis), 1872

- Cezara, 1876

- Avatarii Faraonului Tla, postum

- Geniu pustiu (Deserted genius), novel, posthumous

Presence in English language anthologies

- Testament – Anthology of Modern Romanian Verse / Testament – Antologie de Poezie Română Modernă – Bilingual Edition English & Romanian – Daniel Ioniță (editor and translator) with Eva Foster and Daniel Reynaud – Minerva Publishing 2012 and 2015 (second edition) – ISBN 978-973-21-1006-5

- Testament – Anthology of Romanian Verse – American Edition - monolingual English language edition – Daniel Ioniță (editor and principal translator) with Eva Foster, Daniel Reynaud and Rochelle Bews – Australian-Romanian Academy for Culture – 2017 – ISBN 978-0-9953502-0-5

- The Bessarabia of My Soul / Basarabia Sufletului Meu - a collection of poetry from the Republic of Moldova – bilingual English/Romanian – Daniel Ioniță and Maria Tonu (editors), with Eva Foster, Daniel Reynaud and Rochelle Bews – MediaTon, Toronto, Canada – 2018 – ISBN 978-1-7751837-9-2

- Testament – 400 Years of Romanian Poetry – 400 de ani de poezie românească – bilingual edition – Daniel Ioniță (editor and principal translator) with Daniel Reynaud, Adriana Paul & Eva Foster – Editura Minerva, 2019 – ISBN 978-973-21-1070-6

- Romanian Poetry from its Origins to the Present – bilingual edition English/Romanian – Daniel Ioniță (editor and principal translator) with Daniel Reynaud, Adriana Paul and Eva Foster – Australian-Romanian Academy Publishing – 2020 – ISBN 978-0-9953502-8-1 ; LCCN 2020-907831

Romanian culture

Eminescu was only 20 when Titu Maiorescu, the top literary critic in Romania, dubbed him "a real poet", in an essay where only a handful of the Romanian poets of the time were spared Maiorescu's harsh criticism. In the following decade, Eminescu's notability as a poet grew continually thanks to (1) the way he managed to enrich the literary language with words and phrases from all Romanian regions, from old texts, and with new words that he coined from his wide philosophical readings; (2) the use of bold metaphors, much too rare in earlier Romanian poetry; (3) last but not least, he was arguably the first Romanian writer who published in all Romanian provinces and was constantly interested in the problems of Romanians everywhere. He defined himself as a Romantic, in a poem addressed To My Critics (Criticilor mei), and this designation, his untimely death as well as his bohemian lifestyle (he never pursued a degree, a position, a wife or fortune) had him associated with the Romantic figure of the genius. As early as the late 1880s, Eminescu had a group of faithful followers. His 1883 poem Luceafărul was so notable that a new literary review took its name after it.

The most realistic psychological analysis of Eminescu was written by I. L. Caragiale, who, after the poet's death published three short articles on this subject: In Nirvana, Irony and Two notes. Caragiale stated that Eminescu's characteristic feature was the fact that "he had an excessively unique nature".[30] Eminescu's life was a continuous oscillation between introvert and extrovert attitudes.[31]

That's how I knew him back then, and that is how he remained until his last moments of well-being: cheerful and sad; sociable and crabbed; gentle and abrupt; he was thankful for everything and unhappy about some things; here he was as abstemious as a hermit, there he was ambitious to the pleasures of life; sometimes he ran away from people and then he looked for them; he was carefree as a Stoic and choleric as an edgy girl. Strange medley! – happy for an artist, unhappy for a man!

The portrait that Titu Maiorescu made in the study Eminescu and poems emphasizes Eminescu's introvert dominant traits. Titu Maiorescu promoted the image of a dreamer who was far away from reality, who did not suffer because of the material conditions that he lived in, regardless of all the ironies and eulogies of his neighbour, his main characteristic was "abstract serenity".[32]

In reality, just as one can discover from his poems and letters and just as Caragiale remembered, Eminescu was seldom influenced by boisterous subconscious motivations. Eminescu's life was but an overlap of different-sized cycles, made of sudden bursts that were nurtured by dreams and crises due to the impact with reality. The cycles could last from a few hours or days to weeks or months, depending on the importance of events, or could even last longer, when they were linked to the events that significantly marked his life, such as his relation with Veronica, his political activity during his years as a student, or the fact that he attended the gatherings at the Junimea society or the articles he published in the newspaper Timpul. He used to have a unique manner of describing his own crisis of jealousy.[33]

You must know, Veronica, that as much as I love you, I sometimes hate you; I hate you without a reason, without a word, only because I imagine you laughing with someone else, and your laughter doesn't mean to him what it means to me and I feel I grow mad at the thought of somebody else touching you, when your body is exclusively and without impartasion to anyone. I sometimes hate you because I know you own all these allures that you charmed me with, I hate you when I suspect you might give away my fortune, my only fortune. I could only be happy beside you if we were far away from all the other people, somewhere, so that I didn't have to show you to anybody and I could be relaxed only if I could keep you locked up in a bird house in which only I could enter.

National poet

Eminescu was soon proclaimed Romania's national poet, not because he wrote in an age of national revival, but rather because he was received as an author of paramount significance by Romanians in all provinces. Even today, he is considered the national poet of Romania, Moldova, and of the Romanians who live in Bukovina (Romanian: Bucovina).[citation needed]

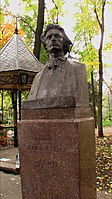

Iconography

Eminescu is omnipresent in today's Romania. His statues are everywhere;[34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41] his face was on the 1000-lei banknotes issued in 1991, 1992, and 1998, and is on the 500-lei banknote issued in 2005 as the highest-denominated Romanian banknote (see Romanian leu); Eminescu's Linden Tree is one of the country's most famous natural landmarks, while many schools and other institutions are named after him. The anniversaries of his birth and death are celebrated each year in many Romanian cities, and they became national celebrations in 1989 (the centennial of his death) and 2000 (150 years after his birth, proclaimed Eminescu's Year in Romania).

Several young Romanian writers provoked a huge scandal when they wrote about their demystified idea of Eminescu and went so far as to reject the "official" interpretation of his work.[42]

International legacy

Romanian composer Didia Saint Georges (1888-1979) used Eminescu’s text for her songs.[43]

A monument jointly dedicated to Eminescu and Allama Iqbal was erected in Islamabad, Pakistan on 15 January 2004, commemorating Pakistani-Romanian ties, as well as the dialogue between civilizations which is possible through the cross-cultural appreciation of their poetic legacies.

Composer Rodica Sutzu used Eminescu's text for her song “Gazel, opus 15.”

In 2004, the Mihai Eminescu Statue was erected in Montreal, Quebec, Canada.[44]

On 8 April 2008, a crater on the planet Mercury was named for him.[45]

A boulevard passing by the Romanian embassy in Sofia, Bulgaria is named after Eminescu.

Academia Internationala presents "Mihai Eminescu" Academy Awards. In 2012, one of the winners, the Japanese artist Shogoro Shogoro hosted a tea ceremony to honor Mihai. [46]

In 2021, the Dutch artist Kasper Peters performs a theater show entitled "Eminescu", dedicated to the poet.

On 15 January 2023, the first monument in Spain in honor of Mihai Eminescu was erected in the city of Rivas-Vaciamadrid. A memorial bench is located in front of the library. Federico Garcia Lorca at the city's Constitution Square.[47]

In May 2024, the first Eminescu sculpture was opened in Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan.[48][49]

In Romania, there are at least 133 monuments (statues and busts) dedicated to Mihai Eminescu. Most of these are located in the region of Moldova (42), followed by Transylvania (32). In Muntenia, there are 21 such monuments, while in Oltenia Eminescu is commemorated through 11 busts. The remaining monuments are placed in Crișana (8), Maramureș (7), and Dobrogea (3).[50]

- Monuments to Mihai Eminescu (selection)

-

Mihai Eminescu statue, Iași

-

Eminescu's Linden Tree, Copou Park, Iași

-

Mihai Eminescu statue, Chișinău, Moldova

-

Mihai Eminescu, monument by Tudor Cataraga, Chișinău, Moldova

-

Mihai Eminescu plaque, Recanati, Italy

Political views

Due to his conservative nationalistic views, Eminescu was easily adopted as an icon by the Romanian right.

After a decade when Eminescu's works were criticized as "mystic" and "bourgeois", Romanian Communists ended by adopting Eminescu as the major Romanian poet. What opened the door for this thaw was the poem Împărat și proletar (Emperor and proletarian) that Eminescu wrote under the influence of the 1870–1871 events in France, and which ended in a Schopenhauerian critique of human life. An expurgated version only showed the stanzas that could present Eminescu as a poet interested in the fate of proletarians.

It has also been revealed that Eminescu demanded strong anti-Jewish legislation on the German model, saying, among other things, that "the Jew does not deserve any rights anywhere in Europe because he is not working".[51] This was a fairly usual stance in the cultural and literary milieu of his age.[52]

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ "Părinții, frații, surorile lui Mihai Eminescu". Tribuna (in Romanian). 15 January 2013.

- ^ Mircea Mâciu dr., Nicolae C. Nicolescu, Valeriu Șuteu dr., Mic dicționar enciclopedic, Ed. Stiinţifică şi enciclopedică, București, 1986

- ^ Biblioteca Academiei – Program de accesare digitala a manuscriselor Archived 21 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine – Mihai Eminescu

- ^ Titu Maiorescu, Eminescu şi poeziile lui (1889) (secţiunea "Notă asupra zilei şi locului naşterii lui Eminescu")

- ^ Ion Roșu, Legend and truth in the biography of M. Eminescu, Cartea romaneasca, 1989, p. 201

- ^ Mihai Eminescu, Luceafărul, International Litera Publishing House, Bucharest, 2001, p. 7

- ^ Dan Stănescu. "Neamul și numele lui Eminescu. Originile, Confluențe literare, 10 ianuarie 2014".

- ^ Dan Stănescu. "Neamul și numele lui Eminescu. Originile, Confluențe literare, 10 ianuarie 2014".

- ^ Dan Stănescu. "Neamul și numele lui Eminescu. Originile, Confluențe literare, 10 ianuarie 2014".

- ^ Călinescu, The Life of Mihai Eminescu, p. 16

- ^ Eminescu commemorative, Artistic-literary album, compiled by Octav Minar, Iasi, 1909

- ^ Dictionary of literature..., p. 321

- ^ Călinescu, Viata lui Mihai Eminescu, p. 30

- ^ Călinescu, George (1989). Viaţa lui Mihai Eminescu [The Life of Mihai Eminescu] (in Romanian). Literatura Artistică. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-973-21-0096-7.

După unii, deci, Eminescu este, prin origine, suedez. El ar fi fost nepot de fiu al unui ofiţer de cavalerie invalid din oastea lui Carol al XII lea, stabilit după bătălia de la Poltava la Suceava, pe lângă familia baronului Mustaţă [...] După mamă, Eminescu pare, însă, indiscutabil, rus.

- ^ Călinescu, Viata lui Mihai Eminescu, p. 31

- ^ Călinescu, "Mihai Eminescu's Life", p. 18-19

- ^ Dr. V. Branisce, "The dowry of Mihai Eminescu's parents", Convorbiri literare, LVIII, 1926, p. 44-48

- ^ Călinescu, "The Life of Mihai Eminescu", p. 20

- ^ Homage to Mihai Eminescu ', Commemoration Committee, Galați, Bucharest, 1909

- ^ Călinescu, Istoria literaturii..., p. 25

- ^ a b Constantinescu, Nicolae M. (September 2014). Bolile lui Eminescu – adevăr şi mistificare [Eminescu's illnesses – between truth and mystification] (in Romanian). Vol. 3. Science Policy and Scientometry Magazine.

- ^ a b "MIHAI EMINESCU a fost asasinat. Teoria conspiraţiei". România TV (in Romanian). 15 June 2014.

- ^ a b c Zamfirache, Cosmin (15 June 2015). "Adevărata cauză a morţii lui Mihai Eminescu. Dezvăluirile specialiștilor, la 126 de ani de la moartea poetului". Adevărul (in Romanian).

- ^ Roseti, Roxana (15 June 2014). "125 de ani de la moartea lui MIHAI EMINESCU. Au pus la cale serviciile SECRETE eliminarea Poetului Naţional?". Evenimentul Zilei (in Romanian).

- ^ a b c Simion, Eugen; Popescu, Irinel; Pop, Ioan-Aurel (15 January 2015). Maladia lui Eminescu și maladiile imaginare ale eminescologilor (in Romanian). Bucharest: National Foundation for Science and Art.

- ^ "Cum a murit Mihai Eminescu. 122 de ani de teorii si presupuneri". Știrile Pro TV (in Romanian). 15 June 2011.

- ^ Neghina, R.; Neghina, A. M. (26 March 2011). "Medical controversies and dilemmas in discussion about the illness and death of Mihai Eminescu (1850–1889), Romania's National Poet". Med. Probl. Performing Artists. 26 (1): 44–50. doi:10.21091/mppa.2011.1007. PMID 21442137.

- ^ "De ce a murit Mihai Eminescu? Răspunsul a 12 dintre cei mai importanți medici români". Digi24 (in Romanian). 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Autor:Mihai Eminescu". wikisource.org.

- ^ I.L. Caragiale, În Nirvana, în Ei l-au văzut pe Eminescu, Antologie de texte de Cristina Crăciun şi Victor Crăciun, Editura Dacia, Cluj-Napoca, 1989, p. 148

- ^ I.L. Caragiale,În Nirvana, în Ei l-au văzut pe Eminescu, Antologie de texte de Cristina Crăciun şi Victor Crăciun, Editura Dacia, Cluj-Napoca, 1989 p. 147

- ^ Titu Maiorescu, Critice, vol. II, Editura pentru literatură, București, 1967, p. 333

- ^ Dulcea mea Doamnă / Eminul meu iubit. Corespondență inedită Mihai Eminescu – Veronica Micle, Editura POLIROM, 2000 p. 157

- ^ Cum arată statuile lui Mihai Eminescu? Comparații la care nu te-ai gândit niciodată, ziaruldeiasi.ro

- ^ Al. Florin Țene / UZPR, Primele busturi şi statui ale lui Eminescu consemnate de ziarişti în presa vremii, uzp.org.ro

- ^ Eminescu – Place de la Roumanie – Montreal (in French)

- ^ Bustul lui Mihai Eminescu din Constanța

- ^ Prof. Victor Macarie – „Monumentul lui Eminescu de la Iași”. In Flacăra Iașului from 15 June 1985.

- ^ Șerban Caloianu și Paul Filip; Monumente Bucureștene, București 2009

- ^ Ministerul Culturii – Lista Monumentelor Istorice, Bustul lui Mihai Eminescu din Băile Herculane

- ^ Statuia lui Eminescu din Galați este păzită zi și noapte, după ce aproape în fiecare an, înainte de 15 ianuarie, se fură mâna muzei, digi24.ro

- ^ "Saitul George Pruteanu "Scandalul" Eminescu... şi replici". pruteanu.ro. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ Reissig, Elfriede; Stefanija, Leon (2 December 2022). Composing Women: 'Femininity' and Views on Cultures, Gender and Music of Southeastern Europe since 1918. Hollitzer Wissenschaftsverlag. ISBN 978-3-99012-997-5.

- ^ "Allama Iqbal and Mihai Eminescu: Dialogue between Civilizatioins(Surprising Resemblance)". pakpost.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 9 August 2009.

- ^ "Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature: Eminescu".

- ^ Rusan, Carmen (1 June 2012). "Premiile Academiei „Mihai Eminescu", la Craiova". Cuvântul Libertăţii (in Romanian). Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ "В Испании открыли первый памятник классику молдавско-румынской литературы". eadaily.com (in Russian). 16 January 2023.

- ^ "Mihai Eminescu". iirmfa.edu.tm. 26 May 2024. Retrieved 10 October 2024.

- ^ Chirtzova, Svetlana (29 May 2024). "Literary voyage through the Magtymguly Fragi cultural and park complex". turkmenistan.gov.tm. Retrieved 10 October 2024.

- ^ Rusu, Mihai S. (7 August 2023). "'Eminescu is everywhere:' charting the memorial spatialization of a national icon". Southeast European and Black Sea Studies: 1–19. doi:10.1080/14683857.2023.2243697. ISSN 1468-3857. S2CID 260728036.

- ^ Ioanid, Radu (1996). Wyman, David S. (ed.). The Worls Reacts to the Holocaust. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 228. ISBN 9780801849695.

- ^ Dietrich, D.J. (1988). "National renewal, anti-Semitism, and political continuity: A psychological assessment". Political Psychology. 9 (3): 385–411. doi:10.2307/3791721. JSTOR 3791721.

Bibliography

- George Călinescu, La vie d'Eminescu, Bucarest: Univers, 1989, 439 p.

- Marin Bucur (ed.), Caietele Mihai Eminescu, București, Editura Eminescu, 1972

- Murărașu, Dumitru (1983), Mihai Eminescu. Viața și Opera, Bucharest: Eminescu.

- Petrescu, Ioana Em. (1972), Eminescu. Modele cosmologice și viziune poetică, Bucharest: Minerva.

- Dumitrescu-Bușulenga, Zoe (1986), Eminescu și romantismul german, Bucharest: Eminescu.

- Bhose, Amita (1978), Eminescu şi India, Iași: Junimea.

- Ițu, Mircia (1995), Indianismul lui Eminescu, Brașov: Orientul Latin.

- Vianu, Tudor (1930), Poezia lui Eminescu, Bucharest: Cartea Românească.

- Negoițescu, Ion (1970), Poezia lui Eminescu, Iași: Junimea.

- Simion, Eugen (1964), Proza lui Eminescu, Bucharest: Editura pentru literatură.

External links

- "Mihai Eminescu". AudioCarti.eu.

- Gabriel's website – Works both in English and original

- Translated poems by Peter Mamara

- Mihai Eminescu. 10 poems in English translations by Octavian Cocoş (audio)

- Works by Mihai Eminescu at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Mihai Eminescu at the Internet Archive

- Works by Mihai Eminescu at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Romanian Poetry – Mihai Eminescu (English)

- Romanian Poetry – Mihai Eminescu (Romanian)

- Institute for Cultural Memory: Mihai Eminescu – Poetry

- Mihai Eminescu Poesii (bilingual pages English Romanian)

- Mihai Eminescu poetry (with English translations of some of his poems)

- MoldData Literature

- Year 2000: "Mihai Eminescu Year" (includes bio, poems, critiques, etc.)

- The Mihai Eminescu Trust

- The Nation's Poet[usurped]: A recent collection sparks debate over Romania's "national poet" by Emilia Stere

- Eminescu – a political victim : An interview with Nicolae Georgescu in Jurnalul National (in Romanian)

- Mihai Eminescu: Complete works (in Romanian)

- Mihai Eminescu : poezii biografie (in Romanian)