Philipp Otto Runge

Philipp Otto Runge | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait, ca. 1802, Hamburger Kunsthalle | |

| Born | 23 July 1777 |

| Died | 2 December 1810 (aged 33) |

| Resting place | Ohlsdorf Cemetery, Hamburg, Germany (moved from the Church of Saint Peter, Hamburg cemetery in 1935) |

| Known for | Artist: painter and draftsman |

| Notable work | The Hülsenbeck Children, Tageszeiten (Times of Day), The Morning |

| Movement | Romanticism |

Philipp Otto Runge (German: [ˈʁʊŋə]; 1777–1810) was a German artist, draftsman, painter, and color theorist. Runge and Caspar David Friedrich are often regarded as the leading painters of the German Romantic movement.[1]: 51 p. [2]: 443 pp. He is frequently compared with William Blake by art historians, although Runge's short ten-year career is not easy to equate to Blake's career.[3]: 38 pp. [2]: 343 pp. By all accounts he had a brilliant mind and was well versed in the literature and philosophy of his time. He was a prolific letter writer and maintained correspondences and friendships with contemporaries such as Carl Ludwig Heinrich Berger, Caspar David Friedrich, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe,[4] Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Henrik Steffens, and Ludwig Tieck. His paintings are often laden symbolism and allegories.[5][6]: 37 pp. For eight years he planned and refined his seminal project, Tageszeiten (Times of Day), four monumental paintings 50 square meters each, which in turn were only part of a larger collaborative Gesamtkunstwerk that was to include poetry, music, and architecture, but remained unrealized at the time of his death.[7]: 71 p. With it he aspired to abandon the traditional iconography of Christianity in European art and find a new expression for spiritual values through symbolism in landscapes.[1]: 98, 135 pp. One historian stated "In Runge's painting we are clearly dealing with the attempt to present contemporary philosophy in art."[2]: 450 pp. He wrote an influential volume on color theory in 1808, Sphere of Colors, that was published the same year he died.[8]

Runge was born in 1777 in Wolgast, a town in northeast Germany on the Baltic Sea (Swedish Pomerania at that time). He contracted pulmonary tuberculosis at an early age and was in frail health throughout his life. As a youth he attended a school headed by Ludwig Gotthard Kosegarten. His father was a successful merchant and ship owner and Philipp and his older brother Daniel were groomed to follow him in his business. Daniel moved to Hamburg to manage a branch of the family business and Philipp soon followed to serve as an apprentice (ca. 1793 – 96). There he began making contact with poets, publishers, and art collectors such as Matthias Claudius, Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock, Justus Perthes, and Johannes Michael Speckter who encouraged Runge in the arts, philosophy, and intellectual interests. He started taking drawing lessons in Hamburg in 1797 with Heinrich Joachim Herterich and Gerdt Hardorff the Elder and it was only after a several years in Hamburg, in his early twenties, that Runge decided on a career as an artist.[2][7][9][10]

Runge studied painting for three years at the Copenhagen Academy (now the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts), from 1798 to1801 with Jens Juel and Nicolai Abildgaard, where Caspar David Friedrich, three years his senior, had recently preceded him. Runge then attended the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts from 1801 to 1804 studying with Anton Graff and making contact with a broader circle of figures in the burgeoning Romantic movement. The poet and writer Ludwig Tieck was particularly influential in introducing Runge to new literature and the mystical ideas of Jakob Böhme and Novalis. Runge met Pauline Bassenge in Dresden in 1801 when she was 16 years old. They were married in Dresden on April 3, 1804, and soon moved back to Hamburg. They had four children, the youngest born after Runge's death. Runge died of consumption (tuberculosis) in 1810, at the age 33, his life's work spanning little more than ten years. Much of his surviving work was donated to the Hamburger Kunsthalle by his widow Pauline Runge née Bassenge in 1872.[2]: 435, 443–452 pp. [7]: 70–75, 80, & 88 pp. [9][10]

Life and work

Runge was born as the ninth of eleven children in Wolgast, Western Pomerania, then under Swedish rule, in a family of shipbuilders with ties to the Prussian nobility of Sypniewski / von Runge family. As a sickly child he often missed school and at an early age learned the art of scissor-cut silhouettes from his mother, practised by him throughout his life.[10] In 1795 he began a commercial apprenticeship at his older brother Daniel's firm in Hamburg. In 1799 Daniel supported Runge financially to begin study of painting under Jens Juel at the Copenhagen Academy. In 1801 he moved to Dresden to continue his studies, where he met Caspar David Friedrich, Ludwig Tieck, and his future wife Pauline Bassenge. He also began extensive study of the writings of the 17th century mystic Jakob Boehme. In 1803, on a visit to Weimar, Runge unexpectedly met Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and the two formed a friendship based on their common interests in color and art.

In 1804 he married and moved with his wife to Hamburg. Due to imminent war dangers (Napoleonic siege of Hamburg) they relocated in 1805 to his parental home in Wolgast where they remained until 1807. In 1805 Runge's correspondence with Goethe on the subject of his artistic work and color became more intensive. Returning to Hamburg in 1807, he and his brother Daniel formed a new company in which he remained active until the end of his life. In the same year he developed the concept of the color sphere.[11] In 1808 he intensified his work on color, including making disk color mixture experiments. He also published written versions of two local folk fairy tales The fisherman and his wife and The almond tree, later included among the tales of the brothers Grimm. In 1809 Runge completed his work on the manuscript of Farben-Kugel (Color sphere), published in 1810 in Hamburg.[12] In the same year, ill with tuberculosis, Runge painted another self-portrait as well as portraits of his family and brother Daniel. Runge died in Hamburg (annexed by Napoleon I to the First French Empire 1804–15), December 2, 1810. The last of his four children was born on the day after Runge's death.[13]

Runge was of a mystical, deeply Christian turn of mind, and in his artistic work he tried to express notions of the harmony of the universe through symbolism of colour, form, and numbers. He considered blue, yellow, and red to be symbolic of the Christian trinity and equated blue with God and the night, red with morning, evening, and Jesus, and yellow with the Holy Spirit (Runge 1841, I, p. 17).

As with some other romantic artists, Runge was interested in Gesamtkunstwerk, or total art work, which was an attempt to fuse all forms of art. He planned such a work surrounding a series of four paintings called The Times of the Day, designed to be seen in a special building, and viewed to the accompaniment of music and his own poetry. In 1803 Runge had large-format engravings made of the drawings of the Times of the Day series that became commercially successful and a set of which he presented to Goethe. He painted two versions of Morning (Kunsthalle, Hamburg), but the others did not advance beyond drawings. "Morning" was the start of a new type of landscape, one of religion and emotion.

Runge was also one of the best German portraitists of his period; several examples are in Hamburg. His style was rigid, sharp, and intense, at times almost naïve.

Runge and color

Runge's interest in color was the natural result of his work as a painter and of having an enquiring mind. Among his accepted tenets was that "as is known, there are only three colors, yellow, red, and blue" (letter to Goethe of July 3, 1806). His goal was to establish the complete world of colors resulting from mixture of the three, among themselves and together with white and black. In the same lengthy letter, Runge discussed in some detail his views on color order and included a sketch of a mixture circle, with the three primary colors forming an equilateral triangle and, together with their pair-wise mixtures, a hexagon.

He arrived at the concept of the color sphere sometime in 1807, as indicated in his letter to Goethe of November 21 of that year, by expanding the hue circle into a sphere, with white and black forming the two opposing poles. A color mixture solid of a double-triangular pyramid had been proposed by Tobias Mayer in 1758, a fact known to Runge. His expansion of that solid into a sphere appears to have had an idealistic basis rather than one of logical necessity. With his disk color mixture experiments of 1807, he hoped to provide scientific support for the sphere form. Encouraged by Goethe and other friends, he wrote in 1808 a manuscript describing the color sphere, published in Hamburg early in 1810. In addition to a description of the color sphere, it contains an illustrated essay on rules of color harmony and one on color in nature written by Runge's friend Henrik Steffens. An included hand-colored plate shows two different views of the surface of the sphere as well as horizontal and vertical slices showing the organization of its interior (see figure on left).

Runge's premature death limited the impact of this work. Goethe, who had read the manuscript before publication, mentioned it in his Farbenlehre of 1810 as "successfully concluding this kind of effort." It was soon overshadowed by Michel Eugène Chevreul's hemispherical system of 1839. A spherical color order system was patented in 1900 by Albert Henry Munsell, soon replaced with an irregular form of the solid.

Legacy

Runge has been included in numerous major retrospective exhibitions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art's, "German Masters of the Nineteenth Century" and the Hamburg Kunsthalle's, "Runge’s Cosmos". The art critic Robert Hughes has described Runge as "the closest equivalent to William Blake that Germany produced".[14] Runge's painting, The Morning, 1808, is considered to be his greatest work.[15] Morning, was intended to be installed as part of a series of religious murals titled Times of Day; the four paintings were to be installed in a Gothic chapel accompanied by music and poetry, which Runge hoped would be a nucleus for a new religion.[14][15] The series, except for Morning and Day, were never developed beyond a suit of monochrome drawings, four prints gifted by Runge, were displayed in Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's music room.[16] Runge's gestural use and contortions of amaryllises and lilies in Times of Day have been described as a predecessor to similar works produced during the Art Nouveau movement almost 100 years later.[14]

Gallery

All works are oil paintings in the collection of the Hamburger Kunsthalle unless noted otherwise.

-

The Nightingale’s Lesson (1804–05), 105 x 86 cm.

-

The Hülsenbeck Children (1805–06), 131.5 x 143.5 cm.

-

The Artist's Parents (1806), 196 x 131 cm.

-

Rest on the Flight to Egypt, unfinished (1806), 96.5 x 129.5 cm.

-

Peter on the Sea (1806), 116 x 157 cm.

-

Birth of the Human Soul (ca. 1806), 35.5 x 32.7 cm., private collection

Tageszeiten (Times of Day)

-

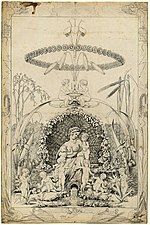

The Day (1803), pen & pencil, 95.1 x 63.1 cm.

-

The Evening (1803), pen & pencil, 95.2 x 64 cm.

-

The Night (1803), pen & pencil, 95.3 x 62.5 cm.

-

The Night (1803), pen & pencil, 71.4 x 48.2 cm.

-

The Morning, small version (1808), 106 x 81 cm.

-

The Great Morning (1809–10), 152 x 113 cm.

-

Detail, The Great Morning (1809–10)

-

Detail, The Great Morning (1809–10)

Portraits

-

Otto Sigismund Runge in a Folding Chair (1805), 40 x 35.5 cm.,

-

We Three, left to right, the artist's brother Daniel, artist's wife Pauline, and self portrait (1805), 100 x 122 cm., destroyed in fire 1931

-

Pauline Runge with Son, wife and son of the artist (1807), 97 x 73 cm., Alte Nationalgalerie

-

Wilhelmina Sophia Helwig (1807), 116 x 92 cm., Pomeranian State Museum

-

Friedrich August von Klinkowström (1808), 65 x 48 cm., Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

-

Portrait of a Young Man (undated), 44 x 35 cm., Österreichische Galerie Belvedere

-

Self-Portrait (1809–10), 48 x 47 cm.

Drawings

-

Self-portrait (ca. 1801–02), black & white chalk, 55.3 x 43.3 cm.

-

The Source and the Poet (1805), ink & pencil, 50.9 x 67.1 cm.

-

Head of a Dog (1805–06), chalk & lead, 29.5 x 35.9 cm.

-

Study for The Great Morning (1809), chalk & pencil, 40.6 x 53.4 cm.

-

Fall of the Fatherland, study (1809), ink & pencil 16.7 x 11 cm.

-

Sophia Sieveking on Her Deathbed (1810), black & white chalk, 43.5 x 51.2 cm.

References

- ^ a b Koerner, Joseph Leo. 1990. Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape. Yale University Press. New Haven, Connecticut. 256 pp. ISBN 0-300-04926-9

- ^ a b c d e Rauch, Alexander. 2000. Neoclassicism and the Romantic Movement: Painting in Europe between Two Revolutions 1789 – 1848. pages 318–479. in Tomam, Rolf, editor. Neoclassicism and Romanticism: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, Drawings, 1750-1848. Könemann, Verlagsgesellschaft. Cologne. 520 pp. ISBN 3-8290-1575-5

- ^ Connelly, Frances S. 1993. Poetic Monsters and Nature Hieroglyphics: The Precocious Primitivism of Philipp Otto Runge. Art Journal. 52(2): 31-39.

- ^ Hellmuth Freiherr von Maltzahn (Hrsg.). 1940. Phillip Otto Runges Briefwechsel mit Goethe. Schriften der Goethe-Gesellschaft (Band 51. Verlag der Goethe-Gesellschaft, Weimar, Deutschland. 120 pp. [Hellmuth Freiherr von Maltzahn (editor). 1940. Phillip Otto Runge's correspondence with Goethe: Volume 51 of Writings of the Goethe Society. Goethe Society. Weimar, Germany. 120 pp.]

- ^ Jaffé, Hans L. C. 1967. 20,000 Years of World Painting. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publication. New York. 418 pp. (page 295)

- ^ Miesel, Victor H. 1972. Philipp Otto Runge, Caspar David Friedrich and Romantic Nationalism. Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin. 33(3): 37-51.

- ^ a b c Bris, Le Michel.1981. Romantics and Romanticism. Editions d'Art Albert Skira. Geneve/Rizzoli International Publications, Inc. New York. 215 pp. ISBN 0-8478-0371-6

- ^ Clay, Jean. 1981. Romanticism. New Jersey: Chartwell Books, Inc. Secaucus. 320 pp. (page 297) ISBN 0-89009-588-4

- ^ a b Claudon, Francis. 1980. The Concise Encyclopedia of Romanticism. Secaucus, N.J.: Chartwell Books. 304 pp. (page 105) ISBN 0-89009-707-0

- ^ a b c Richter, Cornelia. 1981. Philipp Otto Runge, "Ich weiss eine schöne Blume" : Werkverzeichnis der Scherenschnitte [Philipp Otto Runge, "I know a beautiful flower": Catalog Raisonné of the Paper Cuts]. Schirmer-Mosel. Munich, Germany. 143 pp. ISBN 3921375657

- ^ Maltzahn, H. 1940, Philipp Otto Runge's Briefwechsel mit Goethe, Weimar: Verlag der Goethe-Gesellschaft.

- ^ Runge, P. O. 1810, Die Farben-Kugel, oder Construction des Verhaeltnisses aller Farben zueinander, Hamburg: Perthes.

- ^ Runge, P. O. 1840/41, Hinterlassene Schriften', 2. vols., D. Runge, ed., Hamburg: Perthes.'

- ^ a b c Hughes, Robert, 1938-2012. (1990). Nothing if not critical : selected essays on art and artists (1st ed.). New York: A.A. Knopf. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-307-80959-9. OCLC 707239996.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b German masters of the nineteenth century : paintings and drawings from the Federal Republic of Germany. Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), Art Gallery of Ontario. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1981. p. 190. ISBN 0-87099-263-5. OCLC 8052223.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Philipp Otto Runge's Times of Day". The Getty Research Institute.

External links

- P. O. Runge, the artist

- Works by Philipp Otto Runge at Open Library

- "Works by Philipp Otto Runge". Zeno.org (in German).

- Works in the Web Gallery of Art

- Downloadable text of P. F. Schmidt "Philipp Otto Runge; sein Leben und sein Werk", Leipzig: Insel Verlag 1923

- Runge-Haus in Wolgast

- Available English translation of "Farben-Kugel" and supporting materials

- German masters of the nineteenth century: paintings and drawings from the Federal Republic of Germany, a full text exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which contains material on Philipp Otto Runge (no. 70–73)