Mercury(II) chloride

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC names

Mercury(II) chloride

Mercury dichloride | |

| Other names

Mercury bichloride

Corrosive sublimate Abavit Mercuric chloride Sulema (Russia) TL-898 Agrosan Hydrargyri dichloridum (homeopathy) | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.454 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1624 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| HgCl2 | |

| Molar mass | 271.52 g/mol |

| Appearance | colorless or white solid |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 5.43 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 276 °C (529 °F; 549 K) |

| Boiling point | 304 °C (579 °F; 577 K) |

| 3.6 g/100 mL (0 °C) 7.4 g/100 mL (20 °C) 48 g/100 mL (100 °C) | |

| Solubility | 4 g/100 mL (ether) soluble in alcohol, acetone, ethyl acetate slightly soluble in benzene, CS2, pyridine |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.2 (0.2M solution) |

| −82.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.859 |

| Structure | |

| orthogonal | |

| linear | |

| linear | |

| zero | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

144 J·mol−1·K−1[1] |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−230 kJ·mol−1[1] |

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵)

|

-178.7 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| D08AK03 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Highly toxic, corrosive. |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H300+H310+H330, H301, H314, H341, H361f, H372, H410 | |

| P201, P202, P260, P264, P270, P273, P280, P281, P301+P310, P301+P330+P331, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P308+P313, P310, P314, P321, P330, P363, P391, P405, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

32 mg/kg (rats, orally) |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 0979 |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Mercury(II) fluoride Mercury(II) bromide Mercury(II) iodide |

Other cations

|

Zinc chloride Cadmium chloride Mercury(I) chloride |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Mercury(II) chloride (or mercury bichloride[citation needed], mercury dichloride), historically also known as sulema or corrosive sublimate,[2] is the inorganic chemical compound of mercury and chlorine with the formula HgCl2, used as a laboratory reagent. It is a white crystalline solid and a molecular compound that is very toxic to humans. Once used as a treatment for syphilis, it is no longer used for medicinal purposes because of mercury toxicity and the availability of superior treatments.

Synthesis

Mercuric chloride is obtained by the action of chlorine on mercury or on mercury(I) chloride. It can also be produced by the addition of hydrochloric acid to a hot, concentrated solution of mercury(I) compounds such as the nitrate:[2]

- Hg2(NO3)2 + 4 HCl → 2 HgCl2 + 2 H2O + 2 NO2

Heating a mixture of solid mercury(II) sulfate and sodium chloride also affords volatile HgCl2, which can be separated by sublimation.[2]

Properties

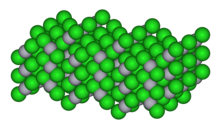

Mercuric chloride exists not as a salt composed of discrete ions, but rather is composed of linear triatomic molecules, hence its tendency to sublime. In the crystal, each mercury atom is bonded to two chloride ligands with Hg–Cl distance of 2.38 Å; six more chlorides are more distant at 3.38 Å.[3]

Its solubility increases from 6% at 20 °C (68 °F) to 36% at 100 °C (212 °F).

Applications

The main application of mercuric chloride is as a catalyst for the conversion of acetylene to vinyl chloride, the precursor to polyvinyl chloride:

- C2H2 + HCl → CH2=CHCl

For this application, the mercuric chloride is supported on carbon in concentrations of about 5 weight percent. This technology has been eclipsed by the thermal cracking of 1,2-dichloroethane. Other significant applications of mercuric chloride include its use as a depolarizer in batteries and as a reagent in organic synthesis and analytical chemistry (see below).[4] It is being used in plant tissue culture for surface sterilisation of explants such as leaf or stem nodes.

As a chemical reagent

Mercuric chloride is occasionally used to form an amalgam with metals, such as aluminium.[5] Upon treatment with an aqueous solution of mercuric chloride, aluminium strips quickly become covered by a thin layer of the amalgam. Normally, aluminium is protected by a thin layer of oxide, thus making it inert. Amalgamated aluminium exhibits a variety of reactions not observed for aluminium itself. For example, amalgamated aluminum reacts with water generating Al(OH)3 and hydrogen gas. Halocarbons react with amalgamated aluminium in the Barbier reaction. These alkylaluminium compounds are nucleophilic and can be used in a similar fashion to the Grignard reagent. Amalgamated aluminium is also used as a reducing agent in organic synthesis. Zinc is also commonly amalgamated using mercuric chloride.

Mercuric chloride is used to remove dithiane groups attached to a carbonyl in an umpolung reaction. This reaction exploits the high affinity of Hg2+ for anionic sulfur ligands.

Mercuric chloride may be used as a stabilising agent for chemicals and analytical samples. Care must be taken to ensure that detected mercuric chloride does not eclipse the signals of other components in the sample, such as is possible in gas chromatography.[6]

History

Discovery of the mineral acids

Around 900, the authors of the Arabic writings attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan (Latin: Geber) and the Persian physician and alchemist Abu Bakr al-Razi (Latin: Rhazes) were experimenting with sal ammoniac (ammonium chloride), which when it was distilled together with vitriol (hydrated sulfates of various metals) produced hydrogen chloride.[7] It is possible that in one of his experiments, al-Razi stumbled upon a primitive method to produce hydrochloric acid.[8] However, it appears that in most of these early experiments with chloride salts, the gaseous products were discarded, and hydrogen chloride may have been produced many times before it was discovered that it can be put to chemical use.[9]

One of the first such uses of hydrogen chloride was in the synthesis of mercury(II) chloride (corrosive sublimate), whose production from the heating of mercury either with alum and ammonium chloride or with vitriol and sodium chloride was first described in the De aluminibus et salibus ("On Alums and Salts").[10] This eleventh- or twelfth-century Arabic alchemical text is anonymous in most manuscripts, though some manuscripts attribute it to Hermes Trismegistus, and a few falsely attribute it to Abu Bakr al-Razi.[11] It was translated into Hebrew and two times into Latin, with one Latin translation by Gerard of Cremona (1144–1187).[12]

In the process described in the De aluminibus et salibus, hydrochloric acid started to form, but it immediately reacted with the mercury to produce mercury(II) chloride. Thirteenth-century Latin alchemists, for whom the De aluminibus et salibus was one of the main reference works, were fascinated by the chlorinating properties of mercury(II) chloride, and they eventually discovered that when the metals are eliminated from the process of heating vitriols, alums, and salts, strong mineral acids can directly be distilled.[13]

Historical use in photography

Mercury(II) chloride was used as a photographic intensifier to produce positive pictures in the collodion process of the 1800s. When applied to a negative, the mercury(II) chloride whitens and thickens the image, thereby increasing the opacity of the shadows and creating the illusion of a positive image.[14]

Historical use in preservation

For the preservation of anthropological and biological specimens during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, objects were dipped in or were painted with a "mercuric solution". This was done to prevent the specimens' destruction by moths, mites and mold. Objects in drawers were protected by scattering crystalline mercuric chloride over them.[15] It finds minor use in tanning, and wood was preserved by kyanizing (soaking in mercuric chloride).[16] Mercuric chloride was one of the three chemicals used for railroad tie wood treatment between 1830 and 1856 in Europe and the United States. Limited railroad ties were treated in the United States until there were concerns over lumber shortages in the 1890s.[17] The process was generally abandoned because mercuric chloride was water-soluble and not effective for the long term, as well as being highly poisonous. Furthermore, alternative treatment processes, such as copper sulfate, zinc chloride, and ultimately creosote; were found to be less toxic. Limited kyanizing was used for some railroad ties in the 1890s and early 1900s.[18]

Historic use in medicine

Mercuric chloride was a common over-the-counter disinfectant in the early twentieth century, recommended for everything from fighting measles germs[19] to protecting fur coats[20] and exterminating red ants.[21] A New York physician, Carlin Philips, wrote in 1913 that "it is one of our most popular and effective household antiseptics", but so corrosive and poisonous that it should only be available by prescription.[22] A group of physicians in Chicago made the same demand later the same month. The product frequently caused accidental poisonings and was used as a suicide method.[23]

It was used to disinfect wounds by Arab physicians in the Middle Ages.[24] It continued to be used by Arab physicians into the twentieth century, until modern medicine deemed it unsafe for use.

Syphilis was frequently treated with mercuric chloride before the advent of antibiotics. It was inhaled, ingested, injected, and applied topically. Both mercuric-chloride treatment for syphilis and poisoning during the course of treatment were so common that the latter's symptoms were often confused with those of syphilis. This use of "salts of white mercury" is referred to in the English-language folk song "The Unfortunate Rake".[25]

Yaws was treated with mercuric chloride (labeled as Corrosive Sublimate) before the advent of antibiotics. It was applied topically to alleviate ulcerative symptoms. Evidence of this is found in Jack London's book The Cruise of the Snark in the chapter entitled "The Amateur M.D."

Between 1901 and 1904 the US Marines Hospital Service quarantined and engaged in an extensive disinfection program of San Francisco's Chinatown, forcing the closure of over 14,000 rooms and eviction of thousands of Chinese whose dwellings were rendered toxic and uninhabitable from the disinfection program. Long-term mercury pollution is still a concern for construction workers in Chinatown to this day.[26]

Historic use in crime and accidental poisonings

- In 1613, whilst imprisoned in the Tower of London, Thomas Overbury was poisoned with an enema of mercury sublimate.[27] The following trial saw the downfall of the murderers, Robert Carr and his wife, Frances.

- In Volume V of Alexandre Dumas' Celebrated Crimes, he recounts the history of Antoine François Desrues, who killed noblewoman Madame de Lamotte with "corrosive sublimate."[28]

- In 1906 in New York, Richard Tilghman died after mistaking bichloride of mercury tablets for lithium citrate.[29]

- Actor Lon Chaney's estranged wife Cleva attempted suicide by swallowing mercuric chloride in 1913. Although the attempt failed, the toxic effects ruined her singing career.[30]

- In a highly publicized case in 1920, mercury bichloride was reported to have caused the death of 25-year-old American silent film star Olive Thomas. While vacationing in France, she accidentally (or perhaps intentionally) ingested the compound, which had been prescribed to her husband Jack Pickford in liquid topical form to treat his syphilis. Thomas died five days later.[31][32]

- Mercuric chloride was used by Madge Oberholtzer to commit suicide after she was kidnapped, raped and tortured by Ku Klux Klan leader D.C. Stephenson. She died from a combination of mercury poisoning and the staph infection that she suffered when Stephenson bit her during the assault.[33]

- Ana María Cires, a young wife of Uruguayan writer Horacio Quiroga, committed suicide by poison. After a violent fight with Quiroga, she ingested a fatal dose of "sublimado", or mercury chloride. She endured great agony for eight days before dying on December 14, 1915.[34]

- Ruth L. Truffant's death was called a suicide after she died from bichloride of mercury poisoning on 26 April 1914.[35][36]

Toxicity

Mercury dichloride is a highly toxic compound,[37] both acutely and as a cumulative poison. Its toxicity is due not just to its mercury content but also to its corrosive properties, which can cause serious internal damage, including ulcers to the stomach, mouth, and throat, and corrosive damage to the intestines. Mercuric chloride also tends to accumulate in the kidneys, causing severe corrosive damage which can lead to acute kidney failure. However, mercuric chloride, like all inorganic mercury salts, does not cross the blood–brain barrier as readily as organic mercury, although it is known to be a cumulative poison.

Common side effects of acute mercuric chloride poisoning include burning sensations in the mouth and throat, stomach pain, abdominal discomfort, lethargy, vomiting of blood, corrosive bronchitis, severe irritation to the gastrointestinal tract, and kidney failure. Chronic exposure can lead to symptoms more common with mercury poisoning, such as insomnia, delayed reflexes, excessive salivation, bleeding gums, fatigue, tremors, and dental problems.

Acute exposure to large amounts of mercuric chloride can cause death in as little as 24 hours, usually due to acute kidney failure or damage to the gastrointestinal tract. In other cases, victims of acute exposure have taken up to two weeks to die.[38]

References

- ^ a b Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A22. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ^ a b c Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 197.

- ^ Wells, A.F. (1984) Structural Inorganic Chemistry, Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-855370-6.

- ^ Matthias Simon, Peter Jönk, Gabriele Wühl-Couturier, Stefan Halbach "Mercury, Mercury Alloys, and Mercury Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2006: Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_269.pub2

- ^ Deng, James; Wang, Yu-Pu; Danheiser, Rick L. (2015). "Synthesis of 4,4-Dimethoxybut-1-yne". Organic Syntheses. 92: 13–25. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.092.0013.

- ^ Foreman, W. T.; Zaugg, S. D.; Faires, L. M.; Werner, M. G.; Leiker, T. J.; Rogerson, P. F. (1992). "Analytical interferences of mercuric chloride preservative in environmental water samples: Determination of organic compounds isolated by continuous liquid-liquid extraction or closed-loop stripping". Environmental Science & Technology. 26 (7): 1307. Bibcode:1992EnST...26.1307F. doi:10.1021/es00031a004.

- ^ Kraus, Paul (1942–1943). Jâbir ibn Hayyân: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque. Cairo: Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. ISBN 9783487091150. OCLC 468740510. vol. II, pp. 41–42; Multhauf, Robert P. (1966). The Origins of Chemistry. London: Oldbourne. OCLC 977570829. pp. 141-142.

- ^ Stapleton, Henry E.; Azo, R.F.; Hidayat Husain, M. (1927). "Chemistry in Iraq and Persia in the Tenth Century A.D." Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. VIII (6): 317–418. OCLC 706947607. p. 333. The relevant recipe reads as follows: "Take equal parts of sweet salt, Bitter salt, Ṭabarzad salt, Andarānī salt, Indian salt, salt of Al-Qilī, and salt of Urine. After adding an equal weight of good crystallised Sal-ammoniac, dissolve by moisture, and distil (the mixture). There will distil over a strong water, which will cleave stone (sakhr) instantly." (p. 333) For a glossary of the terms used in this recipe, see p. 322. German translation of the same passage in Ruska, Julius (1937). Al-Rāzī's Buch Geheimnis der Geheimnisse. Mit Einleitung und Erläuterungen in deutscher Übersetzung. Quellen und Studien zur Geschichte der Naturwissenschaften und der Medizin. Vol. VI. Berlin: Springer. p. 182, §5. An English translation of Ruska 1937's translation can be found in Taylor, Gail Marlow (2015). The Alchemy of Al-Razi: A Translation of the "Book of Secrets". CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 9781507778791. pp. 139–140.

- ^ Multhauf 1966, p. 142, note 79.

- ^ Multhauf 1966, pp. 160–163. On the De aluminibus et salibus, see further Ferrario, Gabriele (2004). "Il Libro degli allumi e dei sali: status quaestionis e prospettive di studio". Henoch. 26 (3): 275–296., Ferrario, Gabriele (2007). "Origins and Transmission of the Liber de aluminibus et salibus". In Principe, Lawrence (ed.). Chymists and Chymistry: Studies in the History of Alchemy and Early Modern Chemistry. Sagamore Beach: Science History Publications. pp. 137–148. See also more briefly Ferrario, Gabriele (2009). "An Arabic Dictionary of Technical Alchemical Terms: MS Sprenger 1908 of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (fols. 3r–6r)". Ambix. 56 (1): 36–48. doi:10.1179/174582309X405219. PMID 19831258. S2CID 41045827. pp. 40–43, and the sources cited in Ferrario 2009, p. 38, note 5. See also Moureau, Sébastien (2020). "Min al-kīmiyāʾ ad alchimiam. The Transmission of Alchemy from the Arab-Muslim World to the Latin West in the Middle Ages". Micrologus. 28: 87–141. hdl:2078.1/211340. pp. 106–107.

- ^ Moureau 2020, pp. 106–107. On the false attribution to al-Razi, see Ferrario 2009, pp. 42–43 and the sources cited there. Moureau 2020, p. 117 stresses that the only Latin work which in the current state of research is known to be a translation of an authentic Arabic work by al-Razi is the Liber secretorum Bubacaris, an interpolated paraphrase of al-Razi's Kitāb al-Asrār.

- ^ Moureau 2020, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Multhauf 1966, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Towler, J. (1864). Stereographic negatives and landscape photography. Chapter 28. In: The silver sunbeam: a practical and theoretical textbook of sun drawing and photographic printing. Retrieved on April 13, 2005.

- ^ Goldberg, Lisa (1996). "A History of Pest Control Measures in the Anthropology Collections, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution". JAIC. 35 (1): 23–43. Retrieved April 17, 2005.

- ^ Freeman, M.H. Shupe, T.F. Vlosky, R.P. Barnes, H.M. (2003). Past, present and future of the wood preservation industry Archived 2005-05-03 at the Wayback Machine. Forest Products Journal. 53(10) 8–15. Retrieved on April 17, 2005.

- ^ Pg. 19-75 "Date Nails and Railroad Tie Preservation" (3 vol.; 560 p.), published in 1999 by the Archeology and Forensics Laboratory, University of Indianapolis; Jeffrey A. Oaks

- ^ Oaks, Jeffrey A. "History of Railroad Tie Preservation" (PDF). p. 20-30; p. 64, Table I. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- ^ "Measles Kills Many Children". The Star and Sentinel. Gettysburg, PA. 1908-01-29. Retrieved 2021-09-25.

- ^ "Adventures of Mr. Mouse". The Day Book. Chicago, IL. 1914-05-05. p. 31. Retrieved 2021-09-25.

- ^ Child, Lydia Maria (832). The American Frugal Housewife (12th ed.). p. 21.

- ^ Philips, M.D., Carlin (1913-06-15). "To Keep Deadly Bichloride of Mercury from Family Medicine Shelves". The Times Dispatch. Richmond, VA. Retrieved 2021-09-25.

- ^ "Want Sale of Bichloride of Mercury Restricted". The Day Book. Chicago, IL. 1913-06-23. Retrieved 2021-09-25.

- ^ Maillard, Adam P. Fraise, Peter A. Lambert, Jean-Yves (2007). Principles and Practice of Disinfection, Preservation and Sterilization. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. p. 4. ISBN 978-0470755068.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pimple, K.D.; Pedroni, J.A.; Berdon, V. (2002, July 09). Syphilis in history Archived 2008-04-30 at the Wayback Machine. Poynter Center for the Study of Ethics and American Institutions at Indiana University-Bloomington. Retrieved on April 20, 2008.

- ^ Craddock, Susan (2000). City of Plagues. University of Minnesota Press. p. 138.

- ^ Somerset, Anne (1997). Unnatural Murder: Poison at the Court of James I. Orion Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0753801987.

- ^ Dumas, Alexandre (1895). Celebrated Crimes Volume V: The Cenci. Murat. Derues. G. Barrie & sons. p. 250. Retrieved 30 June 2015 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The times and democrat. [volume] (Orangeburg, S.C.) 1881-current, June 28, 1906, Image 1". 28 June 1906.

- ^ Mysteries and Scandals – Lon Chaney (Season 3, Episode 34). E!. 2000.

- ^ "Bichloride of Mercury Killed Olive Thomas". The Toronto World. September 15, 1920. p. 6. Retrieved August 27, 2018.

- ^ Foster, Charles (2000). Stardust and Shadows: Canadians in Early Hollywood, page 257. Toronto, Canada: Dundurn Press, 2000. ISBN 978-1550023480.

- ^ Daniel O. Linder, "D.C. Stephenson", Testimony, Famous Trials, hosted at University of Missouri Law School, Kansas City

- ^ Brignol, José (1939). Vida y Obra de Horacio Quiroga. Montevido: La Bolsa de los Libros. pp. 211–213.

- ^ "Actress Dies of Poisoning When Heart Balm is Denied". The Indianapolis Star. 27 April 1914. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ The American Library Annual: Including Index to Dates of 1914-1915. New York: R.R. Bowker Company. 1915. p. 155. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ Mercury (II) chloride, toxicity

- ^ "Mercuric chloride"[dead link] in ToxNet: Hazardous Substances data bank. National Institutes of Health (2002, October 31). Retrieved on April 17, 2005. See also the corresponding entry in ToxNet's successor, PubChem.

External links

- Agency for toxic substances and disease registry. (2001, May 25). Toxicological profile for Mercury. Retrieved on April 17, 2005.

- "Mercuric Chloride | HgCl2" in PubChem database. US National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 19 July 2022. Archived 20 July 2022.

- Young, R.(2004, October 6). Toxicity summary for mercury. The risk assessment information system. Retrieved on April 17, 2005.

- ATSDR - ToxFAQs: Mercury

- ATSDR - Public Health Statement: Mercury

- ATSDR - Medical Management Guidelines (MMGs) for Mercury (Hg)

- ATSDR - Toxicological Profile: Mercury

- International Chemical Safety Card 0979

- National Pollutant Inventory - Mercury and compounds Fact Sheet

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Mercury chloride toxicity - includes excerpts from research reports.