General Motors EV1

| General Motors EV1 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | General Motors |

| Production | 1996–1999 |

| Model years |

|

| Assembly | United States: Lansing, Michigan (Lansing Craft Center) |

| Body and chassis | |

| Class | Subcompact car |

| Body style | 2-door coupé |

| Layout | Transverse front-motor, front-wheel drive |

| Powertrain | |

| Electric motor | |

| Transmission | Single-speed reduction integrated with motor and differential |

| Battery |

|

| Electric range |

|

| Plug-in charging | 6.6 kW Magne Charge inductive converter |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 98.9 in (2,510 mm)[1] |

| Length | 169.7 in (4,310 mm)[1] |

| Width | 69.5 in (1,770 mm)[1] |

| Height | 50.5 in (1,280 mm)[1] |

| Curb weight |

|

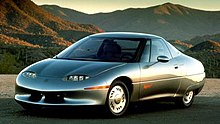

The General Motors EV1 is a battery electric car produced by the American automaker General Motors from 1996 until its demise in 1999.

A subcompact car, the EV1 marked the introduction of mass produced and purpose-built battery electric vehicles.[2][3] The conception of the EV1 dates back to 1990 when GM introduced the battery electric "Impact" prototype, upon which the design of the production EV1 was largely inspired. The California Air Resources Board enacted a mandate in 1990, stating that the seven leading automakers marketing vehicles in the United States must produce and sell zero-emissions vehicles to maintain access to the California market.

Mass production commenced in 1996. In its initial stages of production, most of them were leased to consumers in California, Arizona, and Georgia. Within a year of the EV1's release, leasing programs were also launched in various other American states. In 1998 GM unveiled a series of adaptations for the EV1, encompassing a series hybrid, a parallel hybrid, a compressed natural gas variant, as well as a four-door model, all of which served as prototypes for possible potential future models. Despite favorable customer reception, GM believed that electric cars occupied an unprofitable niche of the automobile market. The company ultimately crushed most of the cars, and in 2001 GM terminated the EV1 program, disregarding protests from customers.

Since its demise, the EV1's cancellation has remained a subject of dispute and controversy. Electric car enthusiasts, environmental interest groups, and former EV1 lessees have accused the company of self-sabotaging its electric car program to avoid potential losses in spare parts sales,[note 1] while also blaming the oil industry for conspiring to keep electric cars off the road.

History

In contrast to numerous electric vehicles of its time, the EV1 was a purpose-built electric vehicle, not a conversion of another car.[4][5] This factor contributed to its significant development cost of US$350 million, as well as its high production costs.[6][7] Kenneth Baker, a General Motors engineer, served as the lead engineer for the EV1 program, having previously served as such for the unsuccessful Chevrolet Electrovette program in the 1970s.[8][9][10]

Origins

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the automobile industry saw little progress in electric car development; over 80 percent of vehicles produced in the United States featured V8 engines.[7][11] But shifts in federal and state regulations began to influence this. The enactment of the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendment and the 1992 Energy Policy Act, alongside the introduction of new transportation emissions regulations by the California Air Resources Board, contributed to a revived interest in electric vehicles in the United States.[7]

In January 1990 GM chairman Roger Smith demonstrated the Impact, a battery electric concept car, at the 1990 Los Angeles Auto Show. GM aimed for a production rate of 100,000 cars per year, as opposed to the initially proposed 20,000.[12] Developed by the electric vehicle company AeroVironment, the Impact drew upon design insights acquired from GM's participation in the 1987 World Solar Challenge. This challenge was a trans-Australia race for solar vehicles, in which the company's Sunraycer was victorious.[13][14][15] Alan Cocconi of AC Propulsion designed and built the original drive system electronics for the Impact, and the design was later refined by Hughes Electronics.[16][17][18] The car was powered by 32 lead–acid rechargeable batteries.[19] On April 18, 1990 Smith announced that the Impact would become a production vehicle with a goal of 25,000 vehicles.[20][21] The Impact achieved a top speed of 183 mph (295 km/h).[22]

Impressed by the feasibility of the Impact and spurred by GM's commitment to produce a minimum of 5,000 units, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) initiated a significant environmental effort in 1990.[23] They mandated that each of the seven largest automakers in the U.S., with GM being the largest among them, must ensure that two percent of their fleet would be emission-free by 1998,[8] increasing to five percent by 2001 and ten percent by 2003, based on consumer demand.[24] The board clarified that the mandate aimed to address California's severe air pollution issue, which, at that time, exceeded the combined pollution levels of the other 49 states.[25] Other participants of the former American Automobile Manufacturers Association, including Toyota, Nissan, and Honda, also individually developed prototype zero-emissions vehicles in response to the new mandate.[26][27]

In 1994, GM initiated "PrEView", a program in which fifty handcrafted Impact electric cars would be loaned to drivers for durations of one to two weeks, with the stipulation that their feedback and experiences would be documented.[28][29] Volunteers were required to possess a garage suitable for the installation of a high-current charging unit by an electric company.[30] Driver response to the cars was favorable, as were reviews by the automotive press. According to Motor Trend, the Impact "is precisely one of those occasions where GM proves beyond any doubt that it knows how to build fantastic automobiles. This is the world's only electric vehicle that drives like a real car." Automobile called the car's ride and handling "amazing", praising its "smooth delivery of power".[31] That year, a modified Impact set a land speed record for production electric vehicles of 183 mph (295 km/h).[32] Despite the good reception, as highlighted in a front-page feature in The New York Times, GM appeared to be less than enthusiastic about the prospect of having created a thriving electric car:

General Motors is preparing to put its electric vehicle act on the road, and planning for a flop. With pride and pessimism, the company, the furthest along of the Big Three in designing a mass-market electric car, says that in the face of a California law that requires that [two] percent of new cars be "zero emission" vehicles beginning in 1997, it has done its best but that the vehicle has come up short. ... Now it hopes that lawmakers and regulators will agree with it and postpone or scrap the deadline.[30]

According to the report, GM viewed the PrEView program as a failure, leading them to believe that the electric car was not yet viable, and that the CARB regulations should be removed. Dennis Minano, GM's vice president for Energy and Environment, questioned whether consumers desired electric vehicles. Robert James Eaton, chairman of Chrysler, also doubted the readiness of mass produced for electric cars, stating in 1994 that "if the law is there, we'll meet it ... at this point of time, nobody can forecast that we can make an electric car". These automakers' skepticism was criticized by Thomas C. Jorling, the Commissioner of Environmental Conservation for New York State, which had adopted the California emission program. According to Jorling, consumers had shown significant interest in electric cars. Jorling suggested that automakers were hesitant to transition from internal combustion engine technology due to their massive investments.[30]

First generation

Following the PrEView initiative, work on the GM electric car program persisted. While the original fifty Impact cars were destroyed after testing was finished, the design had evolved into the GM EV1 by 1996.[19][33] The first generation, often referred to as the "Gen I", would be powered by lead–acid batteries and had a stated range of 70 to 100 miles.[34] A production run of 660 vehicles ensued,[35] with paint options including dark green, red, and silver.[36] The vehicles were offered through a leasing arrangement, explicitly prohibiting the option to buy under a contractual provision (with a suggested retail price listed at $34,000).[37] Saturn assumed responsibility for leasing and maintenance of the EV1.[38] Analysts projected a potential market ranging from 5,000 to 20,000 cars annually.[6]

Similar to the PrEView program, lessees were pre-screened by GM, with only residents of Southern California and Arizona initially eligible for participation.[39][40] Leasing rates for the EV1 ranged from $399 to $549 a month.[41] The car's debut was marked by a significant media event, featuring a US$8 million promotional campaign incorporating prime-time TV commercials, billboards, a dedicated website, and an appearance at the premiere of the Sylvester Stallone film Daylight. Among the initial lessees were notable figures such as celebrities, executives, and politicians. At the release event, 40 EV1 leases were signed, with GM anticipating leasing 100 cars by year's end. Deliveries began on December 5, 1996.[37] In the first year on the market, GM leased just 288 cars.[42] But in 1999 Ken Stewart, the brand manager for the EV1 program, characterized the feedback from the car's drivers as "wonderfully-maniacal loyalty".[43][44]

Joe Kennedy, Saturn's vice president of marketing at GM, acknowledged concerns regarding the EV1's price, the outdated lead–acid battery technology, and the car's restricted range, stating, "Let us not forget that technology starts small and grows slowly before technology improves and costs go down".[37] Some groups opposing taxation expressed disapproval of the exemptions and tax credits given to EV1 lessees, arguing it amounted to government-subsidized driving for affluent individuals.[37] Certain groups, such as the fake consumer organization "Californians Against Utility Company Abuse", which opposed the use of taxpayer funds for public EV charging stations, were accused of being funded by oil companies with interests in maintaining the dominance of gasoline cars.[45]

Marvin Rush, a cinematographer for the TV series Star Trek: Voyager, noticed that GM was not adequately promoting the EV1. Concerned, he personally invested $20,000 to create and broadcast four unofficial radio commercials for the car. Although GM initially opposed this initiative, their stance shifted later on. They decided to endorse the commercials and reimburse Rush for his expenses. In 1997 the company allocated US$10 million for EV1 advertising and pledged to raise this amount by an additional US$5 million the next year.[46]

Second generation

In 1998 for the 1999 model year GM released a second iteration of the EV1. Noteworthy improvements included lower production costs, quieter operation, extensive weight reduction, and the advent of a nickel–metal hydride battery (NiMH).[47] The Gen II models were released with a 60 amp-hour, 312-volt (18.7 kWh, 67.3 MJ) Panasonic lead–acid battery pack.[48] Subsequent models featured an Ovonics NiMH battery, rated at 77 Ah with 343 volts (26.4 kWh, 95.0 MJ).[49] Cars with the lead–acid pack had a range of 80 to 100 miles (130 to 160 km),[50] while the NiMH cars could travel 120 to 140 miles (190 to 230 km) between charges.[14] The second generation EV1 leasing program expanded to several other American cities, with monthly payments ranging from $349 to $574.[51] A total of 457 second generation GM EV1s were produced by the company and leased to customers.[52][53]

On March 2, 2000 GM issued a recall for 450 first generation EV1s. The automaker had determined that a faulty charge port cable could eventually build up enough heat to catch on fire.[54] Sixteen "thermal incidents" were reported, including at least one fire that resulted in the destruction of a charging vehicle.[55] The recall did not affect second generation EV1s.[56]

Costs

GM established lease payments for the EV1 based on an initial vehicle price of US$33,995.[57] Lease payments varied from approximately $299 to $574 per month.[58] An industry official suggested that each EV1 cost the company around US$80,000, including research, development and other associated costs;[59] other estimates placed the vehicle's actual cost as high as $100,000.[57] GM invested slightly less than $500 million into the EV1 and electric vehicle-related technologies,[60] and over $1 billion in total.[61][62]

Design

Construction and technology

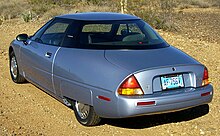

To enhance its efficiency, extensive wind-tunnel testing was conducted on the EV1, and GM additionally implemented partial fender skirts on the rear wheelhouses. The rear wheels are 9 inches (230 mm) closer together than the front wheels, thereby creating the "teardrop" shape. These factors resulted in a very low drag coefficient of Cd=0.19 and a drag area of CdA=3.95 sq ft (0.367 m2).[63][64][65][66] Its design incorporated super-light magnesium alloy wheels and self-sealing, low-rolling resistance tires developed by Michelin rounded out the EV1's good efficiency characteristics.[67][28] These tires, mounted on the lightest fourteen-inch wheels ever used, are inflated to 50 pounds per square inch (psi), compared to the standard 35 psi for normal tires. The special rubber compound utilized in these tires, along with their hardness, contributed to its low rolling resistance.[63]

Its recyclable aluminum structure was the world's lightest, weighing 290 pounds (130 kg).[68] Thus it constituted 10 percent of its overall weight, in comparison to the usual 20 percent. The EV1 features regenerative braking, a system in which applying the brakes turns the drive motor into a generator. This process not only slows down the vehicle but also captures its kinetic energy, returning it to the battery for reuse. To save weight and maximize performance, GM designed the EV1 as a subcompact two-seater vehicle.[69][70][71] Efforts to minimize weight extended to most of the components of the car, including the incorporation of magnesium in the frames of the seats.[71] In addition, the power-assisted anti-lock brakes are electrically activated. The front disc brakes operate on an electro-hydraulic system. The rear drums represent an industry first, being fully electric, which eliminates the requirement for hydraulic lines or parking brake cables.[63]

Traditionally vehicles use heat produced by the engine to heat the passenger compartment. But since electric vehicles generate minimal waste heat, an alternative solution had to be conceived. GM opted for a heat pump to regulate the temperature inside the EV1, consuming a third of the energy required by a traditional unit for both cooling and heating. Nevertheless the system effectively warmed passengers only when temperatures exceed 30 °F (−1 °C). To address colder climates, upcoming electric vehicles were anticipated to incorporate heat pumps alongside compact fuel-fired heaters.[63]

Drivetrain and battery

The electric motor in the EV1 operated on a 3-phase AC induction system, generating 137 brake horsepower (102 kW) at 7,000 revolutions per minute (RPMs).[69][72] The EV1 could maintain its full torque capacity across its entire power range, delivering 110 pound-feet (150 N⋅m) of torque from 0 to 7,000 RPMs.[73][74] Power was transmitted to the front wheels through an integrated single-speed reduction transmission.[75][76][77]

The first generation EV1 models featured lead–acid batteries weighing 1,175 pounds (533 kg).[78][79][80] These batteries, initially supplied by GM's Delco Remy Division, were rated at 53 amp-hours at 312 volts (16.5 kWh), offering an initial range of 60 miles (97 km) per charge.[81][82][36] In 1999 the second generation EV1 cars adopted a new set of lead–acid batteries from the Japanese electronics company Panasonic, increasing the weight to 1,310 pounds (590 kg).[83][84] The batteries were rated at 60 amp-hours at 312 volts (18.7 kWh), extending the EV1's range to 90 miles (145 km).[85] Shortly after the introduction of the second generation cars, the planned nickel–metal hydride (NiMH) "Ovonics" battery pack, developed under the Delco Remy organization, commenced production.[86][87][88] This pack made the car's curb weight 2,908 pounds (1,319 kg).[89] The NiMH batteries were rated at 77 amp-hours at 343 volts (26.4 kWh), providing a range of 160 miles (257 km) per charge, doubling the range of the original first generation cars.[88][90] Charging the NiMH-equipped cars to full capacity could take six to eight hours.[91]

The EV1 used the Magne Charge inductive charging paddle, manufactured by Delco Electronics, a subsidiary of GM.[92][93] This paddle was inserted into a slot located between the EV1's headlights.[84] The wireless charging technology ensured that no direct connection was required, although there were rare instances of fires starting at the charge port.[94][95] For fast recharging of the vehicle, a home charger provided by GM was necessary.[96] In addition to the fast charger, GM offered a 120-volt AC convenience charger for the lead–acid battery that could be utilized with any standard North American power socket for slower charging of the battery pack.[97]

Conversions

GM revealed a family of alternative fuel prototype models at the 1998 Detroit Auto Show.[98] Among these, the compressed natural gas variant was the only model in this family that was not electric, and it was a conversion of the standard two-seat EV1 platform. It featured a 1.0-liter turbocharged engine, and its advertised fuel efficiency was rated at 60 miles per US gallon (3.9 L/100 km; 72 mpg‑imp).[99] The series hybrid prototype featured a auxiliary power unit (APU) housing a gas turbine engine situated in the trunk.[100] Supplied by Williams International, an American manufacturing company founded by Sam B. Williams,[101] the unit comprised a lightweight gas turbine and a high-speed permanent magnet AC generator, the former of which primarily charged the vehicle's batteries.[99][102] The Williams APU had the capability to operate on either compressed natural gas or gasoline. According to GM's assertions, the vehicle could attain 60 miles per US gallon (3.9 L/100 km; 72 mpg‑imp) when running on the latter, offering a total range of 390 miles (630 km). Conversely when operating solely in electric mode, it was estimated to achieve a range of 40 miles (64 km).[103] The parallel hybrid variant featured a 1.3-liter Isuzu turbocharged, direct injection diesel engine, delivering 75 hp (56 kW).[104] GM also introduced a fuel cell variant; its system comprised a fuel processor, an expander/compressor, and a fuel cell stack.[104] Another noteworthy development was the unveiling of a four-passenger variant of the EV1, extended in length by 19 inches (480 mm).[105][106]

Demise

Despite favorable customer reception, GM believed that electric cars occupied an unprofitable niche of the automobile market.[107] The company ended production of the EV1 in 1999, after 1,117 examples were produced over its tenure of under three years.[108][109] On February 7, 2002, Ken Stewart, the brand manager of GM Advanced Technology Vehicles, informed lessees that GM would be recalling the cars from the road,[110] which contradicted a previous statement indicating that GM had no plans to withdraw cars from customers.[111] The EV1 program was terminated in late 2003 under the leadership of then-GM CEO Rick Wagoner.[112][113]

58 EV1 drivers submitted letters along with deposit checks to GM, seeking lease extensions with no financial burden on the automaker. These drivers indicated their willingness to cover maintenance and repair expenses for the EV1, while granting GM the authority to terminate the lease in case of costly repairs. Despite this proposal, in June 2002 GM declined the offer and returned the checks, totalling over US$22,000.[110][114] In November 2003 GM initiated the retrieval of the vehicles;[115] approximately forty units were donated to museums and educational establishments, albeit with deactivated power systems intended to prevent future operation.[116][117] However, most of the vehicles were dispatched to car crushing facilities for demolition.[118][119]

In 2003 Peter Horton, an actor reporting for the Los Angeles Times, sought to lease an EV1 from GM but was informed that he "was welcome to join their waiting list [of a few thousand] along with [an undisclosed number of] others for an indefinite period of time, but his chances of getting a car were slim".[24] In March 2005 GM spokesman Dave Barthmuss discussed the EV1 with The Washington Post, noting that "There [was] an extremely passionate, enthusiastic and loyal following for this particular vehicle [...] There simply [were not] enough of them at any given time to make a viable business proposition for GM to pursue long term".[120]

By the end of August 2004 GM had reclaimed all leased EV1s from their lessees, resulting in the absence of any EV1s on the road. However, one EV1 was showcased at the Main Street in Motion exhibit at Epcot in Walt Disney World, located in Lake Buena Vista, Florida.[118]

Five EV1s were reported to be donated to China in 1998, specifically to the National Electric Vehicle Experimental & Demonstration Area (NEVEDA), a government research institute in Shantou. By 2018, only two EV1s were seen at the facility, while the whereabouts of the three other EV1s were unknown.[121]

Reaction and image

Since its demise and destruction, GM's decision to cancel the EV1 has generated dispute and controversy.[122][123] The American Smithsonian Magazine described the EV1 as "not technically a failure",[124] whereas the Australian Financial Review newspaper contended that while "successful, [the EV1] was doomed to fail".[125] These opinions were due to the economic infeasibility of the EV1, and GM has been acknowledged for discontinuing the EV1, with the newspaper Automotive News asserting that this decision helped GM avoid decades of losses.[126] But despite this praise, many criticized GM's decision to phase out the EV1.[43][120][127] Electric car enthusiasts, environmental interest groups, and former EV1 lessees have accused the company of self-sabotaging its electric car program to avoid potential losses in spare parts sales, while also blaming the oil industry for conspiring to keep electric cars off the road.[128][129]

As car sales declined later in the decade amid the onset of global oil and financial crises, perspectives on the EV1 program underwent a shift. In 2006 Wagoner admitted that his decision to discontinue the EV1 electric-car program and neglect hybrid development was his biggest regret during his tenure at GM. He emphasized that while it didn't directly impact profitability, it did tarnish the company's image.[130] Wagoner reiterated this sentiment in a National Public Radio (NPR) interview following the December 2008 Senate hearings on the U.S. auto industry bailout request.[131] In the March 13, 2007 issue of Newsweek, "GM R&D chief Larry Burns ... now wishes GM hadn't killed the plug-in hybrid EV1 prototype his engineers had on the road a decade ago: 'If we could turn back the hands of time,' says Burns, 'we could have had the [Chevrolet] Volt ten years earlier'",[132] alluding to the Volt considered as the indirect successor to the EV1.[133]

Legacy and post-demise

The demise of the EV1 inspired the conception of the American battery electric carmaker Tesla Motors. Appalled by GM's decision to discontinue and destroy it, Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning established Tesla Motors in July 2003. Just half a year later, Elon Musk provided substantial funding and assumed the role of chairman.[136] Musk stated in a 2017 Twitter post that "Since big car companies were killing their EV programs, the only chance was to create an EV company, even though it was almost certain to fail". He stated in a subsequent tweet that it had "nothing to do with government incentives or making money. I thought there was a 90 probability of losing it all (almost did many times), but it was the only chance".[137][note 2]

Research showed that manufacturers were at least a decade behind in terms of electric vehicle adoption, technology, and infrastructure. While EV1 is considered ahead of its time, it could also be seen as a product of its era and the technologies available at that time. Lead–acid and NiMH batteries had been around for decades, aerodynamics were well understood, and electric motors were already in widespread use.[14]

As part of GM's vehicle electrification strategy,[138] and following the introduction of the Chevrolet Volt plug-in hybrid vehicle to the American market in late 2010, the Chevrolet Spark EV was launched in June 2013. It marked GM's first all-electric passenger car release in the United States since the discontinuation of the EV1 in 1999.[139] The Spark EV was phased out in December 2016, coinciding with the introduction of the Bolt by Chevrolet.[140]

In popular media

The EV1's demise is explored in the 2006 documentary film titled Who Killed the Electric Car?.[141][142] The film covers the history of the electric car, its modern development, and its commercialization. It addresses future concerns regarding air pollution, oil dependency, and climate change. The documentary explores various factors contributing to the EV1's cancellation, including the CARB's decision to reverse the mandate after pressure and lawsuits from automobile manufacturers, influence from the oil industry, anticipation surrounding a future hydrogen car, and the perfidy of the George W. Bush administration. The film extensively covers GM's efforts to convince California that there was no demand for their product, followed by their decision to repossess and dispose of nearly every EV1 manufactured.[143]

The news magazine Time named the EV1 as one of the "50 Worst Cars of All Time". The magazine lauded its design and engineering, stating that it "was a marvel of engineering [and was] absolutely the best electric vehicle anyone had ever seen", but criticized it for being very expensive to build, which led GM executives to terminating the program. They described GM as the company that "killed the electric car".[144]

See also

- Chevrolet Spark EV

- Chevrolet Bolt EV

- Chevrolet Volt

- Chevrolet S-10 EV

- Patent encumbrance of large automotive NiMH batteries

- Battery electric vehicle

- Plug-in electric vehicle

- List of production battery electric vehicles

Notes, citations and sources

Notes

Citations

- ^ a b c d "Automotive Engineering". Automotive Engineering. Vol. 104. United States: Society of Automotive Engineers. 1996. p. 69.

- ^ Adler, Alan L. (1996-09-29). "Electrifying Answers". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ "History of the electric car: from the first EV to the present day". Auto Express. 2020-05-04. Archived from the original on 2023-11-30. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ "Timeline: History of the Electric Car". United States Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 2024-03-22. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Davies, Alex (February 2016). "How GM Beat Tesla to the First True Mass-Market Electric Car". WIRED. Archived from the original on 2024-03-24. Retrieved 2024-03-29.

- ^ a b Fisher, Lawrence M. (1996-01-05). "G.M., in a First, Will Sell a Car Designed for Electric Power This Fall". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2024-03-24. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ a b c "The History of the Electric Car". United States Department of Energy. 2014-09-15. Archived from the original on 2024-03-19. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ a b Nauss, Donald W. (1996-12-05). "GM Rolls Dice With Roll-Out of Electric Car". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2023-02-06. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ Eisler 2022, p. 124.

- ^ Fletcher 2011, p. 226.

- ^ Standage, Tom (2021-08-03). "The lost history of the electric car – and what it tells us about the future of transport". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2024-03-25. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ Stevenson, Richard W. (1990-01-04). "G.M. Displays the Impact, An Advanced Electric Car". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2023-01-20.

General Motors had high hopes that the car could be the first to bridge the gap between limited-production electrical vehicles ... and mass-produced autos. 'It is producable'. most comfortable with 100,000 cars a year, not 20,000. 'It's a total system approach' said John S. Zwerner, a top engineer at General Motors. 'Every detail has been important.'

- ^ Squatriglia, Chuck (2009-02-27). "MIT Unveils 90 MPH Solar Race Car". WIRED. Archived from the original on 2024-03-19. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ a b c Jamieson, Craig. "GM could have led the electric revolution with the EV1". Top Gear. BBC. Archived from the original on 2023-09-30.

- ^ Hales, Linda (2006-04-08). "Coming to a Driveway (or Runway?) Near You". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2017-08-27. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ Fialka 2015, p. 40.

- ^ "Popular Science". Popular Science. Vol. 241, no. 1. Bonnier Corporation. July 1992. ISSN 0161-7370.

- ^ Quandt, Carlos Olavo (February 1995). "Manufacturing the Electric Vehicle: A Window of Technological Opportunity for Southern California". Research Papers in Economics. 27 (6): 835–862. doi:10.1068/a270835. Archived from the original on 2024-03-30. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ a b Wachenheim III 2022, p. 209.

- ^ Eisler 2012, p. 234.

- ^ Cowan & Hultén 2000, p. 108.

- ^ "Ward's Auto World". Ward's Auto World. Vol. 32. United States. 1996. p. 90.

- ^ "Popular Science". Popular Science. Vol. 238, no. 5. Bonnier Corporation. May 1991. p. 76. ISSN 0161-7370.

- ^ a b Horton, Peter (2003-06-08). "Peter Buys an Electric Car". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2023-08-13. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ Shnayerson 1996, p. 50.

- ^ Nilsson 2012, p. 166.

- ^ Graham 2021, p. 120.

- ^ a b Fialka 2015, p. 83.

- ^ United States General Accounting Office (1994). Electric Vehicles: Likely Consequences of U.S. and Other Nations' Programs and Policies: Report to the Chairman, Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, House of Representatives. United States: The Office. p. 54. Archived from the original on 2024-03-30. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ a b c Wald, Matthew L. (1994-01-28). "Expecting a Fizzle, G.M. Puts Electric Car to Test". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2023-08-13. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Shnayerson 1996, p. 183.

- ^ Power Electronics in Transportation. United States: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. 1983. p. 43.

- ^ "EV1: How an electric car dream was crushed". BBC. 2022-01-29. Archived from the original on 2023-12-04. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Florea, Ciprian (2020-08-17). "Nine Early Electric Cars From The 1990s That We Forgot About". Top Speed. Archived from the original on 2024-03-30. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Taylor 2022, p. 41.

- ^ a b Kimble 2015, p. 180.

- ^ a b c d Dean, Paul; Reed, Mack (1996-12-06). "An Electric Start – Media, Billboards, Web Site Herald Launch of the EV1". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2023-10-29. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Truett, Richard (1997-06-26). "GM'S EV1 Blazes the Trail to Tomorrow". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2018-07-20. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Adelson, Andrea (1997-05-07). "G.M. Is Trying to Make a Go Of Its Electric Car". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2023-01-20. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Nauss, Donald W. (1996-11-26). "GM's EV1 Gears Up Amid Charge of the Ad Brigade". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2022-12-05. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Naughton, Keith (1997-12-15). "Detroit: It Isn't Easy Going Green". Business Week. Archived from the original on 2011-06-28. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Thornton, Emily (1997-12-15). "Japan's Hybrid Cars". Business Week. Archived from the original on 2011-06-28. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ a b English, Andrew (2022-01-01). "The story of the first 'modern' electric vehicle". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2023-01-14. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Fletcher 2011, p. 82.

- ^ Parrish, Michael (1994-04-14). "Trying to Pull the Plug: Big Oil Companies Sponsor Efforts to Curtail Electric, Natural Gas Cars". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2020-01-31. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

big oil companies have been largely silent. But now the companies have found their voice—or, more accurately, the voice of others—by quietly bankrolling what on its face appears to be a grass-roots campaign against $600 million in proposed utility investments in alternative-vehicle support systems. A new group called Californians Against Utility Company Abuse—run by Woodward & McDowell, a high-powered Burlingame, Calif.-based public relations firm—gathered petitions and demonstrated Wednesday in front of a regional office of Southern California Gas Co. The group also recently mailed a letter to 200,000 utility ratepayers statewide. It does not mention oil industry support in its literature.

- ^ Gellene, Denise (1998-03-22). "Electric Car Owner Spots GM Some Ads". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Ernst, Kurt (2013-06-27). "Cars of Futures Past - GM EV1". Hemmings Motor News. Archived from the original on 2024-01-14. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Nedelea, Andrei (2012-07-06). "Take a Ride in the Brilliant EV1". Autoevolution. Archived from the original on 2022-07-18. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Katic, Vladimir A.; Dumnic, Boris; Corba, Zoltan; Milicevic, Dragan (June 2014). "Electrification of The Vehicle Propulsion System – An Overview". Electronics and Energetics. 27 (2): 299–316. doi:10.2298/FUEE1402299K.

- ^ Wilson 2023b, p. 109.

- ^ Carpenter, Susan (2011-11-10). "The man behind 'Who Killed the Electric Car?' is back with a sequel". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on 2019-12-18. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Taylor 2022, p. 42.

- ^ Strohl, Daniel (2022-12-05). "How many GM EV1s still exist, and do any of them still run". Hemmings Motor News. Archived from the original on 2024-03-17. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Brown, Warren (2000-03-02). "GM Recalls Hundreds Of Electric Cars, Pickups". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2017-08-28. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Burton 2013, § GM Pulls The Plug.

- ^ O'Dell, John (2000-03-03). "GM Will Tow 450 Original EV1s in Recall". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2023-03-14. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ a b Quiroga, Tony (August 2009). "Driving the Future". Car and Driver. Hachette Filipacchi Media U.S. p. 52.

- ^ Ohnsman, Alan (2006-07-14). "Documentary investigates death of the electric car". Times Colonist. p. 37 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Steele, Jeffrey (2008-08-07). "Who Really pulled the plug?". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on 2023-02-07. Retrieved 2024-04-04.

- ^ Neff, Natalie (1998-05-01). "EV Enthusiasm Needs Recharging - You might say we've been jolted back to reality". Ward's Auto. Archived from the original on 2023-10-04. Retrieved 2024-04-04.

- ^ Maynard, Micheline (2013-07-18). "GM, Which Killed The EV1, Plans To Study Elon Musk's Tesla". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2021-10-29. Retrieved 2024-04-04.

- ^ "GM launches the EV1 and learns a lesson". Automotive News. 2017-01-03. Retrieved 2024-04-04.

- ^ a b c d Nauss, Donald W. (1996-10-14). "GM's Power Move". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2024-03-30. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ Witzenburg, Gary (2021-06-16). "Mythbusting: The truth about the GM EV1". Hagerty. Archived from the original on 2024-03-08. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ Brooke 2011, p. 143.

- ^ Genta & Genta 2016, p. 182.

- ^ Dobrev 2020, p. 8.

- ^ MacKenzie, Angus (2023-02-07). "Ahead of Its Time: How GM's EV1 Lives On in Today's EVs". Motor Trend. Archived from the original on 2024-03-12. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ a b Nikowitz 2016, p. 5.

- ^ Wilson, Kevin A. (2023-04-01). "Worth the Watt: A Brief History of the Electric Car, 1830 to Present". Car and Driver. Archived from the original on 2024-02-05. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ a b Siry, Darryl (2009-12-03). "Dec. 4, 1996: GM Delivers EV1 Electric Car". WIRED. Archived from the original on 2023-01-31. Retrieved 2024-03-30.

- ^ "Car and Driver". Car and Driver. Vol. 42. United States: Ziff-Davis Publishing Company. 1997. p. 83.

- ^ "Road & Track". Road & Track. Vol. 48. United States: CBS Publications. 1997. p. 83.

- ^ Chan & Chau 2001, p. 22.

- ^ Chau 2015, p. 67.

- ^ Winfield, Barry. "Tested: 1997 General Motors EV1 Proves to Be the Start of Something Big". Car and Driver. No. March 1997. Archived from the original on 2024-04-01. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ "Electric Vehicle Progress". Vol. 21, no. 16. United States: Downtown/Urban Research Center. 1999.

- ^ Dorf 2001, p. 388.

- ^ Vance, Bill (2019-05-10). "Bill Vance: General Motors' EV1 was far ahead of its time". Times Colonist. Archived from the original on 2023-10-02. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ "Automotive Engineering International". Automotive Engineering. Vol. 116, no. 7–12. United States: Society of Automotive Engineers. 2008. p. 38.

- ^ Graham 2021, p. 121.

- ^ Strohl, Daniel (2023-02-14). "These nine EVs from the 1990s set the stage for every one of today's electric vehicles". Hemmings Motor News. Archived from the original on 2023-12-16. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Eisler 2022, p. 148.

- ^ a b "Automotive Engineering". Automotive Engineering. Vol. 105, no. 7–12. United States: Society of Automotive Engineers. 1997. p. 12.

- ^ Babu, p. 21.

- ^ Schreffler, Roger (2017-12-28). "Groundbreaking Prius Hybrid Evolves Over 20 Years". Ward's Auto. Archived from the original on 2024-04-01. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ "Scientific American". Scientific American. Vol. 301. United States: Munn & Company. 2009. p. 53. ISSN 0036-8733.

- ^ a b Burton 2013, § The Second Generation.

- ^ Burton 2013, § General Motors EV1 Specification Table.

- ^ Senecal & Leach 2021, p. 106.

- ^ Anderson & Anderson 2010, p. 207.

- ^ "Popular Mechanics". Popular Mechanics. Vol. 173, no. 5. Hearst Magazines. May 1996. p. 19. ISSN 0032-4558.

- ^ "Popular Science". Popular Science. Vol. 249, no. 5. November 1996. p. 82. ISSN 0161-7370.

- ^ Mi & Masrur 2017, p. 250.

- ^ Porter 2014, p. 42.

- ^ Graham 2021, p. 122.

- ^ "Road & Track". Road & Track. Vol. 47. CBS Publications. May 1996. p. 49.

- ^ Fisher, Angie (2013-01-17). "Looking Back: 1998 Detroit Auto Show: Automakers Start To Take Fuel Efficiency Seriously". Autoweek. Crain Communications Inc. ISSN 0192-9674. Archived from the original on 2024-04-02. Retrieved 2024-04-02.

- ^ a b "Popular Science". Popular Science. Vol. 252, no. 5. Bonnier Corporation. May 1998. p. 26. ISSN 0161-7370.

- ^ Un-Noor, Fuad; Padmanaban, Sanjeevikumar; Mihet-Popa, Lucian; Mollah, Mohammad Nurunnabi; Hossain, Eklas (2017-08-17). "A Comprehensive Study of Key Electric Vehicle (EV) Components, Technologies, Challenges, Impacts, and Future Direction of Development". Energies. 10 (8): 1217. doi:10.3390/en10081217. hdl:11250/2501252.

- ^ Lehto & Leno 2010, p. 181.

- ^ "Autocar". Autocar. Vol. 215. United Kingdom: Haymarket Motoring Publishing. 1998. p. 12. ISSN 1355-8293.

- ^ Day, Lewin (2024-01-02). "The World's First Look At The Secret EV1 Electric Convertible That GM Killed 10 Years Before The Tesla Roadster". The Autopian. Archived from the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2024-04-02.

- ^ a b Hydrogen & Fuel Cell Letter. Vol. 13–15. United States: Peter Hoffmann. 1998. p. 5.

- ^ "1998 Auto Show Detroit". Automotive News. 1998-01-05. ISSN 0005-1551. Archived from the original on 2024-04-02. Retrieved 2024-04-02.

- ^ "Sports Cars Illustrated". Sports Cars Illustrated. Vol. 43. United States: Hachette Magazines, Incorporated. March 1998. p. 46. ISSN 0008-6002.

- ^ Taylor, Michael (2005-04-24). "Owners charged up over electric cars, but manufacturers have pulled the plug". SFGate. Hearst Newspapers. Archived from the original on 2023-10-26. Retrieved 2024-04-02.

- ^ Wheeler 2007, p. 9.

- ^ Fialka 2015, p. 86.

- ^ a b Mieszkowski, Katharine (2002-09-04). "Steal this car!". Salon. Salon Media Group. Archived from the original on 2019-06-18. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- ^ "GM: Hybrids, Fuel Cells, and the Lawyers" (PDF). Convention and Tradeshow News. 2001-12-12. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-02-24.

'Nowhere in this plan am I going out and taking cars off the road from customers,' he says, 'without the customer requesting it first.'

- ^ "Letters to the Editor: GM, killer of its first electric car, now wants to spend billions on them?". Los Angeles Times. 2020-03-11. Archived from the original on 2024-04-02. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ "Pulling the plug on an electric dream". The Sunday Times. 2006-07-30. Archived from the original on 2024-04-02. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Guilford, Dave (2002-11-11). "EV1 lessees to GM: Don't take our cars". Automotive News. Archived from the original on 2021-05-17. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Voelker, John (2011-09-03). "GM riles electric car advocates over charger sharing". Reuters. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Kelly, Zachariah (2022-08-23). "The GM EV1 Is a Legendary Electric Car That Should Have Been a Holden". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 2023-11-15. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Fessler 2019, p. 124.

- ^ a b Stoklosa, Alexander (2019-12-06). "GM Supposedly Destroyed (Nearly) Every EV1 Ever Made—So Why Is One in an Atlanta Parking Garage?". Motor Trend. Archived from the original on 2024-03-30. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Hales, Linda (2006-06-16). "An Electric Car, Booted". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2017-08-27. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ a b Schneider, Greg; Edds, Kimberly (2005-03-10). "Fans of GM Electric Car Fight the Crusher". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2016-03-25. Retrieved 2016-06-11.

- ^ Faulkner, Sam (2018-10-16). "A brief history of the National Electric Vehicle Experimental & Demonstration Area". ChinaCarHistory. Retrieved 2024-08-27.

- ^ Morris, James (2021-02-20). "Why Nobody Will Kill The Electric Car This Time". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2024-04-03. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Woodard, Colin (2016-11-24). "Remember When GM Was America's Leading Electric Carmaker?". Road and Track. Archived from the original on 2023-09-27. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Edwards, Owen (June 2006). "The Death of the EV-1". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 2024-03-01. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Davis, Tony (2023-06-20). "GM had an electric car in 1998. Why did it fail?". Australian Financial Review. Archived from the original on 2023-06-28. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ "Despite demise, EV1 was a risk worth taking". Automotive News. 2021-04-19. Archived from the original on 2021-04-19. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Biederman, Patricia Ward (2005-03-12). "Vigil an Outlet for EV1 Fans". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2022-12-07. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Blazev 2021, p. 1171.

- ^ Williams 2010, p. 80.

- ^ "Motor Trend". Motor Trend. No. 5. United States. June 1996. p. 94. ISSN 0027-2094.

- ^ Norris, Michele (2008-12-04). "GM CEO Outlines Company's Plans". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 2008-12-21. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- ^ Caryl, Christian; Kashiwagi, Akiko (2008-07-12). "Toyota is on track to pass General Motors this year as the world's No. 1 auto company. How GM plans to fight back". Newsweek International. Archived from the original on 2008-12-23. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith (2011-09-20). "G.M. Plans to Develop Electric Cars With China". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2023-05-14. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ "A brief history of Tesla: inside the Petersen Museum retrospective". Car. 2022-11-29. Archived from the original on 2023-03-07. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Eisler 2022, p. 147.

- ^ Sherman, Don (2020-01-23). "The EV1 may have been first, but its demise launched Tesla". Hagerty. Archived from the original on 2023-07-30. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Thomas, Lauren (2017-06-09). "Elon Musk: We started Tesla after big auto companies tried to 'kill' the electric car". CNBC. Archived from the original on 2023-09-23. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Brinkman, Norman; Eberle, Ulrich; Formanski, Volker; Grebe, Uwe-Dieter; Matthe, Roland (2012-04-15). "Vehicle Electrification – Quo Vadis". VDI. Archived from the original on 2014-12-22. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- ^ Jerry Garrett (2012-11-28). "2014 Chevrolet Spark EV: Worth the Extra Charge?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2014-11-07. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ^ Burden, Melissa (2017-01-31). "Chevy axes Spark EV in favor of Bolt EV". The Detroit News. Archived from the original on 2021-10-08. Retrieved 2021-10-07.

- ^ Crothers, Brooke (2023-07-09). "GM Lost A 10-Year Battle With Tesla, Pulling The Plug On A Long Line Of EVs". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2024-04-03. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

- ^ Spencer 2010, p. 28.

- ^ Saad 2016, § 1. Topics Addressed.

- ^ Neil, Dan (2017-04-25). "The 50 Worst Cars of All Time". Time. Archived from the original on 2020-05-13. Retrieved 2024-04-03.

Sources

- Anderson, Curtis D.; Anderson, Judy (2010-03-30). Electric and Hybrid Cars. United States: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-5742-7.

- Babu, A. K. Electric & Hybrid Vehicles. India: Khanna Publishing House. ISBN 978-9-3861-7371-3.

- Blazev, Anco S. (2021) [2014]. Power Generation and the Environment. United Kingdom: River Publishers. ISBN 978-8-7702-2310-2.

- Brooke, Lindsay (2011). Chevrolet Volt: Development Story of the Pioneering Electrified Vehicle. United States: SAE International. ISBN 978-0-7680-5783-6.

- Burton, Nigel (2013). History of Electric Cars. United Kingdom: Crowood Press. ISBN 978-1-8479-7571-3.

- Chan, C. C.; Chau, K. T. (2001). Modern Electric Vehicle Technology. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1985-0416-0.

- Chau, K. T. (2015). Electric Vehicle Machines and Drives: Design, Analysis and Application. Germany: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-1187-5261-6.

- Cowan, Robin; Hultén, Staffan (2000). Electric Vehicles: Socio-economic Prospects and Technological Challenges. United Kingdom: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-1399-2.

- Dobrev, Ivelin (2020). Tesla's Current State and Brand Potential. How to Derive a Brand Meaning and Create a Future that Inspires. Germany: Science Factory. ISBN 978-3-9648-7261-6.

- Dorf, Richard C. (2001). Technology, Humans, and Society: Toward a Sustainable World. Ukraine: Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-0805-1865-7.

- Eisler, Matthew N. (2012). Overpotential: Fuel Cells, Futurism, and the Making of a Power Panacea. United States: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-5177-7.

- Eisler, Matthew N. (2022). Age of Auto Electric: Environment, Energy, and the Quest for the Sustainable Car. United Kingdom: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-2623-7203-9.

- Fessler, David C. (2019) [2018]. The Energy Disruption Triangle: Three Sectors That Will Change How We Generate, Use, and Store Energy. United Kingdom: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-1193-4711-8.

- Fialka, John J. (2015). Car Wars: The Rise, the Fall, and the Resurgence of the Electric Car. United States: St. Martin's Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4668-4960-0.

- Fletcher, Seth (2011). Bottled Lightning: Superbatteries, Electric Cars, and the New Lithium Economy. United States: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-1-4299-2291-3.

- Genta, Giancarlo; Genta, Alessandro (2016). Road Vehicle Dynamics: Fundamentals Of Modeling And Simulation. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-8008-8013-9.

- Graham, John D. (2021). The Global Rise of the Modern Plug-In Electric Vehicle: Public Policy, Innovation and Strategy. United Kingdom: Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-8008-8013-9.

- Hayes, John G.; Goodarzi, Gordon Abas (2018) [2017]. Electric Powertrain. United Kingdom: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-1190-6364-3.

- Kimble, David (2015). David Kimble's Cutaways: The Techniques and the Stories Behind the Art. United States: CarTech. ISBN 978-1-6132-5173-7.

- Lehto, Steve; Leno, Jay (2010). Chrysler's Turbine Car. United States: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-5697-6771-9.

- Mi, Chris; Masrur, M. Abul (2017) [2011]. Hybrid Electric Vehicles: Principles and Applications with Practical Perspectives. Germany: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-1189-7053-9.

- Nikowitz, Michael (2016). Advanced Hybrid and Electric Vehicles: System Optimization and Vehicle Integration. Germany: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-3192-6305-2.

- Nilsson, Måns (2012). Paving the Road to Sustainable Transport: Governance and Innovation in Low-carbon Vehicles. United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-4156-8360-9.

- Porter, Richard (2014). Top Gear; Epic Failures: 50 Great Motoring Cock-Ups. United Kingdom: BBC Books. ISBN 978-1-8499-0820-7.

- Saad, Fouad (2016). The Shock of Energy Transition. Singapore: Partridge Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4828-6495-3.

- Senecal, Peter Kelly; Leach, Felix (2021). Racing Toward Zero: The Untold Story of Driving Green. United States: SAE International. ISBN 978-1-4686-0146-6.

- Shnayerson, Michael (1996). The Car that Could: The Inside Story of GM's Revolutionary Electric Vehicle. United States: Random House. ISBN 978-0-6794-2105-4.

- Spencer, Zack (2010) [2009]. Motormouth: The Complete Canadian Car Guide. United Kingdom: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-4709-6415-6.

- Taylor, James (2022). Electric Cars. United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-7844-2494-7.

- Wachenheim III, Edgar (2022) [2016]. Common Stocks and Common Sense: The Strategies, Analyses, Decisions, and Emotions of a Particularly Successful Value Investor. United Kingdom: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-1199-1324-5.

- Wheeler, Jill C. (2007). Alternative Cars. United States: ABDO Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-6178-4807-0.

- Williams, Chris (2010). Ecology and Socialism. United States: Haymarket Books. ISBN 978-1-6084-6091-5.

- Wilson, Kevin A. (2023b). The Electric Vehicle Revolution: The Past, Present, and Future of EVs. United States: Motorbooks. ISBN 978-0-7603-7831-1.

External links

- Eulogy for the EV 1, EV World (archived through the Wayback Machine)

- Emissions-free car on trial, The Boston Globe (archived through the Wayback Machine)