Chicago

Chicago | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Etymology: Miami-Illinois: shikaakwa ('wild onion' or 'wild garlic') | |

| Nicknames: Windy City and others | |

| Mottoes: Latin: Urbs in Horto (City in a Garden); I Will | |

Interactive map of Chicago | |

| Coordinates: 41°52′55″N 87°37′40″W / 41.88194°N 87.62778°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| Counties | Cook (majority) and DuPage (minority) |

| Settled | c. 1780 |

| Incorporated (town) | August 12, 1833 |

| Incorporated (city) | March 4, 1837 |

| Founded by | Jean Baptiste Point du Sable |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Body | Chicago City Council |

| • Mayor | Brandon Johnson (D) |

| • City Clerk | Anna Valencia (D) |

| • City Treasurer | Melissa Conyears-Ervin (D) |

| Area | |

| • City | 234.53 sq mi (607.44 km2) |

| • Land | 227.73 sq mi (589.82 km2) |

| • Water | 6.80 sq mi (17.62 km2) |

| Elevation [1] (mean) | 597.18 ft (182.02 m) |

| Highest elevation – near Blue Island | 672 ft (205 m) |

| Lowest elevation – at Lake Michigan | 578 ft (176 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 2,746,388 |

| • Estimate (2022)[3] | 2,665,039 |

| • Rank | |

| • Density | 12,059.84/sq mi (4,656.33/km2) |

| • Urban | 8,671,746 (US: 3rd) |

| • Urban density | 3,709.2/sq mi (1,432.1/km2) |

| • Metro | 9,618,502 (US: 3rd) |

| Demonym | Chicagoan |

| GDP | |

| • Chicago (MSA) | $832.9 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−06:00 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−05:00 (CDT) |

| ZIP Code prefixes | 606xx, 607xx, 608xx |

| Area codes | 312, 773, 872 |

| FIPS code | 17-14000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0428803 |

| Website | chicago |

Chicago[a] is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 census,[9] it is the third-most populous city in the United States after New York City and Los Angeles. As the seat of Cook County, the second-most populous county in the U.S., Chicago is the center of the Chicago metropolitan area, often colloquially called "Chicagoland" and home to 9.6 million residents.

Located on the shore of Lake Michigan, Chicago was incorporated as a city in 1837 near a portage between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River watershed. It grew rapidly in the mid-19th century.[10][11] In 1871, the Great Chicago Fire destroyed several square miles and left more than 100,000 homeless,[12] but Chicago's population continued to grow.[11] Chicago made noted contributions to urban planning and architecture, such as the Chicago School, the development of the City Beautiful movement, and the steel-framed skyscraper.[13][14]

Chicago is an international hub for finance, culture, commerce, industry, education, technology, telecommunications, and transportation. It has the largest and most diverse derivatives market in the world, generating 20% of all volume in commodities and financial futures alone.[15] O'Hare International Airport is routinely ranked among the world's top six busiest airports by passenger traffic,[16] and the region is also the nation's railroad hub.[17] The Chicago area has one of the highest gross domestic products (GDP) of any urban region in the world, generating $689 billion in 2018.[18] Chicago's economy is diverse, with no single industry employing more than 14% of the workforce.[15]

Chicago is a major destination for tourism, including visitors to its cultural institutions, and Lake Michigan beaches. Chicago's culture has contributed much to the visual arts, literature, film, theater, comedy (especially improvisational comedy), food, dance, and music (particularly jazz, blues, soul, hip-hop, gospel,[19] and electronic dance music, including house music). Chicago is home to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the Lyric Opera of Chicago, while the Art Institute of Chicago provides an influential visual arts museum and art school. The Chicago area also hosts the University of Chicago, Northwestern University, and the University of Illinois Chicago, among other institutions of learning. Professional sports in Chicago include all major professional leagues, including two Major League Baseball teams.

Etymology and nicknames

The name Chicago is derived from a French rendering of the indigenous Miami-Illinois word shikaakwa for a wild relative of the onion; it is known to botanists as Allium tricoccum and known more commonly as "ramps". The first known reference to the site of the current city of Chicago as "Checagou" was by Robert de LaSalle around 1679 in a memoir.[20] Henri Joutel, in his journal of 1688, noted that the eponymous wild "garlic" grew profusely in the area.[21] According to his diary of late September 1687:

... when we arrived at the said place called "Chicagou" which, according to what we were able to learn of it, has taken this name because of the quantity of garlic which grows in the forests in this region.[21]

The city has had several nicknames throughout its history, such as the Windy City, Chi-Town, Second City, and City of the Big Shoulders.[22]

History

Beginnings

In the mid-18th century, the area was inhabited by the Potawatomi, an indigenous tribe who had succeeded the Miami, Sauk and Meskwaki peoples in this region.[23]

The first known permanent settler in Chicago was trader Jean Baptiste Point du Sable. Du Sable was of African descent, perhaps born in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (Haiti), and established the settlement in the 1780s. He is commonly known as the "Founder of Chicago".[24][25][26]

In 1795, following the victory of the new United States in the Northwest Indian War, an area that was to be part of Chicago was turned over to the U.S. for a military post by native tribes in accordance with the Treaty of Greenville. In 1803, the U.S. Army constructed Fort Dearborn, which was destroyed during the War of 1812 in the Battle of Fort Dearborn by the Potawatomi before being later rebuilt.[27]

After the War of 1812, the Ottawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi tribes ceded additional land to the United States in the 1816 Treaty of St. Louis. The Potawatomi were forcibly removed from their land after the 1833 Treaty of Chicago and sent west of the Mississippi River as part of the federal policy of Indian removal.[28][29][30]

19th century

On August 12, 1833, the Town of Chicago was organized with a population of about 200.[30] Within seven years it grew to more than 6,000 people. On June 15, 1835, the first public land sales began with Edmund Dick Taylor as Receiver of Public Monies. The City of Chicago was incorporated on Saturday, March 4, 1837,[31] and for several decades was the world's fastest-growing city.[32]

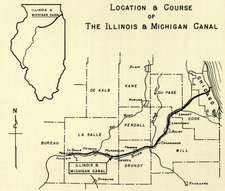

As the site of the Chicago Portage,[33] the city became an important transportation hub between the eastern and western United States. Chicago's first railway, Galena and Chicago Union Railroad, and the Illinois and Michigan Canal opened in 1848. The canal allowed steamboats and sailing ships on the Great Lakes to connect to the Mississippi River.[34][35][36][37]

A flourishing economy brought residents from rural communities and immigrants from abroad. Manufacturing and retail and finance sectors became dominant, influencing the American economy.[38] The Chicago Board of Trade (established 1848) listed the first-ever standardized "exchange-traded" forward contracts, which were called futures contracts.[39]

In the 1850s, Chicago gained national political prominence as the home of Senator Stephen Douglas, the champion of the Kansas–Nebraska Act and the "popular sovereignty" approach to the issue of the spread of slavery.[40] These issues also helped propel another Illinoisan, Abraham Lincoln, to the national stage. Lincoln was nominated in Chicago for U.S. president at the 1860 Republican National Convention, which was held in a purpose-built auditorium called the Wigwam. He defeated Douglas in the general election, and this set the stage for the American Civil War.

To accommodate rapid population growth and demand for better sanitation, the city improved its infrastructure. In February 1856, Chicago's Common Council approved Chesbrough's plan to build the United States' first comprehensive sewerage system.[41] The project raised much of central Chicago to a new grade with the use of jackscrews for raising buildings.[42] While elevating Chicago, and at first improving the city's health, the untreated sewage and industrial waste now flowed into the Chicago River, and subsequently into Lake Michigan, polluting the city's primary freshwater source.

The city responded by tunneling two miles (3.2 km) out into Lake Michigan to newly built water cribs. In 1900, the problem of sewage contamination was largely resolved when the city completed a major engineering feat. It reversed the flow of the Chicago River so that the water flowed away from Lake Michigan rather than into it. This project began with the construction and improvement of the Illinois and Michigan Canal, and was completed with the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal that connects to the Illinois River, which flows into the Mississippi River.[43][44][45]

In 1871, the Great Chicago Fire destroyed an area about 4 miles (6.4 km) long and 1-mile (1.6 km) wide, a large section of the city at the time.[46][47][48] Much of the city, including railroads and stockyards, survived intact,[49] and from the ruins of the previous wooden structures arose more modern constructions of steel and stone. These set a precedent for worldwide construction.[50][51] During its rebuilding period, Chicago constructed the world's first skyscraper in 1885, using steel-skeleton construction.[52][53]

The city grew significantly in size and population by incorporating many neighboring townships between 1851 and 1920, with the largest annexation happening in 1889, with five townships joining the city, including the Hyde Park Township, which now comprises most of the South Side of Chicago and the far southeast of Chicago, and the Jefferson Township, which now makes up most of Chicago's Northwest Side.[54] The desire to join the city was driven by municipal services that the city could provide its residents.

Chicago's flourishing economy attracted huge numbers of new immigrants from Europe and migrants from the Eastern United States. Of the total population in 1900, more than 77% were either foreign-born or born in the United States of foreign parentage. Germans, Irish, Poles, Swedes, and Czechs made up nearly two-thirds of the foreign-born population (by 1900, whites were 98.1% of the city's population).[55][56]

Labor conflicts followed the industrial boom and the rapid expansion of the labor pool, including the Haymarket affair on May 4, 1886, and in 1894 the Pullman Strike. Anarchist and socialist groups played prominent roles in creating very large and highly organized labor actions. Concern for social problems among Chicago's immigrant poor led Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr to found Hull House in 1889.[57] Programs that were developed there became a model for the new field of social work.[58]

During the 1870s and 1880s, Chicago attained national stature as the leader in the movement to improve public health. City laws and later, state laws that upgraded standards for the medical profession and fought urban epidemics of cholera, smallpox, and yellow fever were both passed and enforced. These laws became templates for public health reform in other cities and states.[59]

The city established many large, well-landscaped municipal parks, which also included public sanitation facilities. The chief advocate for improving public health in Chicago was John H. Rauch, M.D. Rauch established a plan for Chicago's park system in 1866. He created Lincoln Park by closing a cemetery filled with shallow graves, and in 1867, in response to an outbreak of cholera he helped establish a new Chicago Board of Health. Ten years later, he became the secretary and then the president of the first Illinois State Board of Health, which carried out most of its activities in Chicago.[60]

In the 1800s, Chicago became the nation's railroad hub, and by 1910 over 20 railroads operated passenger service out of six different downtown terminals.[61][62] In 1883, Chicago's railway managers needed a general time convention, so they developed the standardized system of North American time zones.[63] This system for telling time spread throughout the continent.

In 1893, Chicago hosted the World's Columbian Exposition on former marshland at the present location of Jackson Park. The Exposition drew 27.5 million visitors, and is considered the most influential world's fair in history.[64][65] The University of Chicago, formerly at another location, moved to the same South Side location in 1892. The term "midway" for a fair or carnival referred originally to the Midway Plaisance, a strip of park land that still runs through the University of Chicago campus and connects the Washington and Jackson Parks.[66][67]

20th and 21st centuries

1900 to 1939

During World War I and the 1920s there was a major expansion in industry. The availability of jobs attracted African Americans from the Southern United States. Between 1910 and 1930, the African American population of Chicago increased dramatically, from 44,103 to 233,903.[68] This Great Migration had an immense cultural impact, called the Chicago Black Renaissance, part of the New Negro Movement, in art, literature, and music.[69] Continuing racial tensions and violence, such as the Chicago race riot of 1919, also occurred.[70]

The ratification of the 18th amendment to the Constitution in 1919 made the production and sale (including exportation) of alcoholic beverages illegal in the United States. This ushered in the beginning of what is known as the gangster era, a time that roughly spans from 1919 until 1933 when Prohibition was repealed. The 1920s saw gangsters, including Al Capone, Dion O'Banion, Bugs Moran and Tony Accardo battle law enforcement and each other on the streets of Chicago during the Prohibition era.[71] Chicago was the location of the infamous St. Valentine's Day Massacre in 1929, when Al Capone sent men to gun down members of a rival gang, North Side, led by Bugs Moran.[72]

From 1920 to 1921, the city was affected by a series of tenant rent strikes in it. Which lead to the formation of the Chicago Tenants Protective association, passage of the Kessenger tenant laws, and of a heat ordinance that legally required flats to be kept above 68 °F during winter months by landlords.[73][74][75][76][77][78]

Chicago was the first American city to have a homosexual-rights organization. The organization, formed in 1924, was called the Society for Human Rights. It produced the first American publication for homosexuals, Friendship and Freedom. Police and political pressure caused the organization to disband.[79]

The Great Depression brought unprecedented suffering to Chicago, in no small part due to the city's heavy reliance on heavy industry. Notably, industrial areas on the south side and neighborhoods lining both branches of the Chicago River were devastated; by 1933 over 50% of industrial jobs in the city had been lost, and unemployment rates amongst blacks and Mexicans in the city were over 40%. The Republican political machine in Chicago was utterly destroyed by the economic crisis, and every mayor since 1931 has been a Democrat.[80]

From 1928 to 1933, the city witnessed a tax revolt, and the city was unable to meet payroll or provide relief efforts. The fiscal crisis was resolved by 1933, and at the same time, federal relief funding began to flow into Chicago.[80] Chicago was also a hotbed of labor activism, with Unemployed Councils contributing heavily in the early depression to create solidarity for the poor and demand relief; these organizations were created by socialist and communist groups. By 1935 the Workers Alliance of America begun organizing the poor, workers, the unemployed. In the spring of 1937 Republic Steel Works witnessed the Memorial Day massacre of 1937 in the neighborhood of East Side.

In 1933, Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak was fatally wounded in Miami, Florida, during a failed assassination attempt on President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1933 and 1934, the city celebrated its centennial by hosting the Century of Progress International Exposition World's Fair.[81] The theme of the fair was technological innovation over the century since Chicago's founding.[82]

1940 to 1979

During World War II, the city of Chicago alone produced more steel than the United Kingdom every year from 1939 – 1945, and more than Nazi Germany from 1943 – 1945.[83]

The Great Migration, which had been on pause due to the Depression, resumed at an even faster pace in the second wave, as hundreds of thousands of blacks from the South arrived in the city to work in the steel mills, railroads, and shipping yards.[84]

On December 2, 1942, physicist Enrico Fermi conducted the world's first controlled nuclear reaction at the University of Chicago as part of the top-secret Manhattan Project. This led to the creation of the atomic bomb by the United States, which it used in World War II in 1945.[85]

Mayor Richard J. Daley, a Democrat, was elected in 1955, in the era of machine politics. In 1956, the city conducted its last major expansion when it annexed the land under O'Hare airport, including a small portion of DuPage County.[86]

By the 1960s, white residents in several neighborhoods left the city for the suburban areas – in many American cities, a process known as white flight – as Blacks continued to move beyond the Black Belt.[87] While home loan discriminatory redlining against blacks continued, the real estate industry practiced what became known as blockbusting, completely changing the racial composition of whole neighborhoods.[88] Structural changes in industry, such as globalization and job outsourcing, caused heavy job losses for lower-skilled workers. At its peak during the 1960s, some 250,000 workers were employed in the steel industry in Chicago, but the steel crisis of the 1970s and 1980s reduced this number to just 28,000 in 2015. In 1966, Martin Luther King Jr. and Albert Raby led the Chicago Freedom Movement, which culminated in agreements between Mayor Richard J. Daley and the movement leaders.[89]

Two years later, the city hosted the tumultuous 1968 Democratic National Convention, which featured physical confrontations both inside and outside the convention hall, with anti-war protesters, journalists and bystanders being beaten by police.[90] Major construction projects, including the Sears Tower (now known as the Willis Tower, which in 1974 became the world's tallest building), University of Illinois at Chicago, McCormick Place, and O'Hare International Airport, were undertaken during Richard J. Daley's tenure.[91] In 1979, Jane Byrne, the city's first female mayor, was elected. She was notable for temporarily moving into the crime-ridden Cabrini-Green housing project and for leading Chicago's school system out of a financial crisis.[92]

1980 to present

In 1983, Harold Washington became the first black mayor of Chicago. Washington's first term in office directed attention to poor and previously neglected minority neighborhoods. He was re‑elected in 1987 but died of a heart attack soon after.[93] Washington was succeeded by 6th ward alderperson Eugene Sawyer, who was elected by the Chicago City Council and served until a special election.

Richard M. Daley, son of Richard J. Daley, was elected in 1989. His accomplishments included improvements to parks and creating incentives for sustainable development, as well as closing Meigs Field in the middle of the night and destroying the runways. After successfully running for re-election five times, and becoming Chicago's longest-serving mayor, Richard M. Daley declined to run for a seventh term.[94][95]

In 1992, a construction accident near the Kinzie Street Bridge produced a breach connecting the Chicago River to a tunnel below, which was part of an abandoned freight tunnel system extending throughout the downtown Loop district. The tunnels filled with 250 million US gallons (1,000,000 m3) of water, affecting buildings throughout the district and forcing a shutdown of electrical power.[96] The area was shut down for three days and some buildings did not reopen for weeks; losses were estimated at $1.95 billion.[96]

On February 23, 2011, Rahm Emanuel, a former White House Chief of Staff and member of the House of Representatives, won the mayoral election.[97] Emanuel was sworn in as mayor on May 16, 2011, and won re-election in 2015.[98] Lori Lightfoot, the city's first African American woman mayor and its first openly LGBTQ mayor, was elected to succeed Emanuel as mayor in 2019.[99] All three city-wide elective offices were held by women (and women of color) for the first time in Chicago history: in addition to Lightfoot, the city clerk was Anna Valencia and the city treasurer was Melissa Conyears-Ervin.[100]

On May 15, 2023, Brandon Johnson assumed office as the 57th mayor of Chicago.

Geography

Topography

Chicago is located in northeastern Illinois on the southwestern shores of freshwater Lake Michigan. It is the principal city in the Chicago Metropolitan Area, situated in both the Midwestern United States and the Great Lakes region. The city rests on a continental divide at the site of the Chicago Portage, connecting the Mississippi River and the Great Lakes watersheds. In addition to it lying beside Lake Michigan, two rivers—the Chicago River in downtown and the Calumet River in the industrial far South Side—flow either entirely or partially through the city.[101][102]

Chicago's history and economy are closely tied to its proximity to Lake Michigan. While the Chicago River historically handled much of the region's waterborne cargo, today's huge lake freighters use the city's Lake Calumet Harbor on the South Side. The lake also provides another positive effect: moderating Chicago's climate, making waterfront neighborhoods slightly warmer in winter and cooler in summer.[103]

When Chicago was founded in 1837, most of the early building was around the mouth of the Chicago River, as can be seen on a map of the city's original 58 blocks.[104] The overall grade of the city's central, built-up areas is relatively consistent with the natural flatness of its overall natural geography, generally exhibiting only slight differentiation otherwise. The average land elevation is 579 ft (176.5 m) above sea level. While measurements vary somewhat,[105] the lowest points are along the lake shore at 578 ft (176.2 m), while the highest point, at 672 ft (205 m), is the morainal ridge of Blue Island in the city's far south side.[106]

Lake Shore Drive runs adjacent to a large portion of Chicago's waterfront. Some of the parks along the waterfront include Lincoln Park, Grant Park, Burnham Park, and Jackson Park. There are 24 public beaches across 26 miles (42 km) of the waterfront.[107] Landfill extends into portions of the lake providing space for Navy Pier, Northerly Island, the Museum Campus, and large portions of the McCormick Place Convention Center. Most of the city's high-rise commercial and residential buildings are close to the waterfront.

An informal name for the entire Chicago metropolitan area is "Chicagoland", which generally means the city and all its suburbs, though different organizations have slightly different definitions.[108][109][110]

Communities

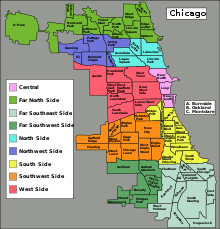

Major sections of the city include the central business district, called the Loop, and the North, South, and West Sides.[111] The three sides of the city are represented on the Flag of Chicago by three horizontal white stripes.[112] The North Side is the most-densely-populated residential section of the city, and many high-rises are located on this side of the city along the lakefront.[113] The South Side is the largest section of the city, encompassing roughly 60% of the city's land area. The South Side contains most of the facilities of the Port of Chicago.[114]

In the late-1920s, sociologists at the University of Chicago subdivided the city into 77 distinct community areas, which can further be subdivided into over 200 informally defined neighborhoods.[115][116]

Streetscape

Chicago's streets were laid out in a street grid that grew from the city's original townsite plot, which was bounded by Lake Michigan on the east, North Avenue on the north, Wood Street on the west, and 22nd Street on the south.[117] Streets following the Public Land Survey System section lines later became arterial streets in outlying sections. As new additions to the city were platted, city ordinance required them to be laid out with eight streets to the mile in one direction and sixteen in the other direction, about one street per 200 meters in one direction and one street per 100 meters in the other direction. The grid's regularity provided an efficient means of developing new real estate property. A scattering of diagonal streets, many of them originally Native American trails, also cross the city (Elston, Milwaukee, Ogden, Lincoln, etc.). Many additional diagonal streets were recommended in the Plan of Chicago, but only the extension of Ogden Avenue was ever constructed.[118]

In 2016, Chicago was ranked the sixth-most walkable large city in the United States.[119] Many of the city's residential streets have a wide patch of grass or trees between the street and the sidewalk itself. This helps to keep pedestrians on the sidewalk further away from the street traffic. Chicago's Western Avenue is the longest continuous urban street in the world.[120] Other notable streets include Michigan Avenue, State Street, 95th Street, Cicero Avenue, Clark Street, and Belmont Avenue. The City Beautiful movement inspired Chicago's boulevards and parkways.[121]

Architecture

The destruction caused by the Great Chicago Fire led to the largest building boom in the history of the nation. In 1885, the first steel-framed high-rise building, the Home Insurance Building, rose in the city as Chicago ushered in the skyscraper era,[53] which would then be followed by many other cities around the world.[122] Today, Chicago's skyline is among the world's tallest and densest.[123]

Some of the United States' tallest towers are located in Chicago; Willis Tower (formerly Sears Tower) is the second tallest building in the Western Hemisphere after One World Trade Center, and Trump International Hotel and Tower is the third tallest in the country.[124] The Loop's historic buildings include the Chicago Board of Trade Building, the Fine Arts Building, 35 East Wacker, and the Chicago Building, 860-880 Lake Shore Drive Apartments by Mies van der Rohe. Many other architects have left their impression on the Chicago skyline such as Daniel Burnham, Louis Sullivan, Charles B. Atwood, John Root, and Helmut Jahn.[125][126]

The Merchandise Mart, once first on the list of largest buildings in the world, currently listed as 44th-largest 2013 as September 9, 2013, had its own zip code until 2008, and stands near the junction of the North and South branches of the Chicago River.[127] Presently, the four tallest buildings in the city are Willis Tower (formerly the Sears Tower, also a building with its own zip code), Trump International Hotel and Tower, the Aon Center (previously the Standard Oil Building), and the John Hancock Center. Industrial districts, such as some areas on the South Side, the areas along the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, and the Northwest Indiana area are clustered.[128]

Chicago gave its name to the Chicago School and was home to the Prairie School, two movements in architecture.[129] Multiple kinds and scales of houses, townhouses, condominiums, and apartment buildings can be found throughout Chicago. Large swaths of the city's residential areas away from the lake are characterized by brick bungalows built from the early 20th century through the end of World War II. Chicago is also a prominent center of the Polish Cathedral style of church architecture. The Chicago suburb of Oak Park was home to famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright, who had designed The Robie House located near the University of Chicago.[130][131]

A popular tourist activity is to take an architecture boat tour along the Chicago River.[132]

Monuments and public art

Chicago is famous for its outdoor public art with donors establishing funding for such art as far back as Benjamin Ferguson's 1905 trust.[133] A number of Chicago's public art works are by modern figurative artists. Among these are Chagall's Four Seasons; the Chicago Picasso; Miro's Chicago; Calder's Flamingo; Oldenburg's Batcolumn; Moore's Large Interior Form, 1953-54, Man Enters the Cosmos and Nuclear Energy; Dubuffet's Monument with Standing Beast, Abakanowicz's Agora; and, Anish Kapoor's Cloud Gate which has become an icon of the city. Some events which shaped the city's history have also been memorialized by art works, including the Great Northern Migration (Saar) and the centennial of statehood for Illinois. Finally, two fountains near the Loop also function as monumental works of art: Plensa's Crown Fountain as well as Burnham and Bennett's Buckingham Fountain.[134][135]

Climate

The city lies within the typical hot-summer humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfa), and experiences four distinct seasons.[136][137][138] Summers are hot and humid, with frequent heat waves. The July daily average temperature is 75.4 °F (24.1 °C), with afternoon temperatures peaking at 84.5 °F (29.2 °C). In a normal summer, temperatures reach at least 90 °F (32 °C) on 17 days, with lakefront locations staying cooler when winds blow off the lake. Winters are relatively cold and snowy. Blizzards do occur, such as in winter 2011.[139] There are many sunny but cold days. The normal winter high from December through March is about 36 °F (2 °C). January and February are the coldest months. A polar vortex in January 2019 nearly broke the city's cold record of −27 °F (−33 °C), which was set on January 20, 1985.[140][141][142] Measurable snowfall can continue through the first or second week of April.[143]

Spring and autumn are mild, short seasons, typically with low humidity. Dew point temperatures in the summer range from an average of 55.8 °F (13.2 °C) in June to 61.7 °F (16.5 °C) in July.[144] They can reach nearly 80 °F (27 °C), such as during the July 2019 heat wave. The city lies within USDA plant hardiness zone 6a, transitioning to 5b in the suburbs.[145]

According to the National Weather Service, Chicago's highest official temperature reading of 105 °F (41 °C) was recorded on July 24, 1934.[146] Midway Airport reached 109 °F (43 °C) one day prior and recorded a heat index of 125 °F (52 °C) during the 1995 heatwave.[147] The lowest official temperature of −27 °F (−33 °C) was recorded on January 20, 1985, at O'Hare Airport.[144][147] Most of the city's rainfall is brought by thunderstorms, averaging 38 a year. The region is prone to severe thunderstorms during the spring and summer which can produce large hail, damaging winds, and occasionally tornadoes.[148]

Like other major cities, Chicago experiences an urban heat island, making the city and its suburbs milder than surrounding rural areas, especially at night and in winter. The proximity to Lake Michigan tends to keep the Chicago lakefront somewhat cooler in summer and less brutally cold in winter than inland parts of the city and suburbs away from the lake.[149] Northeast winds from wintertime cyclones departing south of the region sometimes bring the city lake-effect snow.[150]

| Climate data for Chicago (Midway International Airport), 1991–2020 normals,[b] extremes 1928–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

75 (24) |

86 (30) |

92 (33) |

102 (39) |

107 (42) |

109 (43) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

94 (34) |

81 (27) |

72 (22) |

109 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 53.4 (11.9) |

57.9 (14.4) |

72.0 (22.2) |

81.5 (27.5) |

89.2 (31.8) |

93.9 (34.4) |

96.0 (35.6) |

94.2 (34.6) |

90.8 (32.7) |

82.8 (28.2) |

68.0 (20.0) |

57.5 (14.2) |

97.1 (36.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 32.8 (0.4) |

36.8 (2.7) |

47.9 (8.8) |

60.0 (15.6) |

71.5 (21.9) |

81.2 (27.3) |

85.2 (29.6) |

83.1 (28.4) |

76.5 (24.7) |

63.7 (17.6) |

49.6 (9.8) |

37.7 (3.2) |

60.5 (15.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 26.2 (−3.2) |

29.9 (−1.2) |

39.9 (4.4) |

50.9 (10.5) |

61.9 (16.6) |

71.9 (22.2) |

76.7 (24.8) |

75.0 (23.9) |

67.8 (19.9) |

55.3 (12.9) |

42.4 (5.8) |

31.5 (−0.3) |

52.4 (11.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 19.5 (−6.9) |

22.9 (−5.1) |

32.0 (0.0) |

41.7 (5.4) |

52.4 (11.3) |

62.7 (17.1) |

68.1 (20.1) |

66.9 (19.4) |

59.2 (15.1) |

46.8 (8.2) |

35.2 (1.8) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

44.4 (6.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −3 (−19) |

3.4 (−15.9) |

14.1 (−9.9) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

39.1 (3.9) |

49.3 (9.6) |

58.6 (14.8) |

57.6 (14.2) |

45.0 (7.2) |

31.8 (−0.1) |

19.7 (−6.8) |

5.3 (−14.8) |

−6.5 (−21.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −25 (−32) |

−20 (−29) |

−7 (−22) |

10 (−12) |

28 (−2) |

35 (2) |

46 (8) |

43 (6) |

29 (−2) |

20 (−7) |

−3 (−19) |

−20 (−29) |

−25 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.30 (58) |

2.12 (54) |

2.66 (68) |

4.15 (105) |

4.75 (121) |

4.53 (115) |

4.02 (102) |

4.10 (104) |

3.33 (85) |

3.86 (98) |

2.73 (69) |

2.33 (59) |

40.88 (1,038) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 12.5 (32) |

10.1 (26) |

5.7 (14) |

1.0 (2.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

1.5 (3.8) |

7.9 (20) |

38.8 (99) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.5 | 9.4 | 11.1 | 12.0 | 12.4 | 11.1 | 10.0 | 9.3 | 8.4 | 10.8 | 10.2 | 10.8 | 127.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 8.9 | 6.4 | 3.9 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 6.3 | 28.2 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source 1: NOAA[151][144][147], WRCC[152] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV)[153] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Chicago (O'Hare Int'l Airport), 1991–2020 normals,[b] extremes 1871–present[c] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

75 (24) |

88 (31) |

91 (33) |

98 (37) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

102 (39) |

101 (38) |

94 (34) |

81 (27) |

71 (22) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 52.3 (11.3) |

56.8 (13.8) |

71.0 (21.7) |

80.9 (27.2) |

88.0 (31.1) |

93.1 (33.9) |

94.9 (34.9) |

93.2 (34.0) |

89.7 (32.1) |

81.7 (27.6) |

67.0 (19.4) |

56.4 (13.6) |

96.0 (35.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 31.6 (−0.2) |

35.7 (2.1) |

47.0 (8.3) |

59.0 (15.0) |

70.5 (21.4) |

80.4 (26.9) |

84.5 (29.2) |

82.5 (28.1) |

75.5 (24.2) |

62.7 (17.1) |

48.4 (9.1) |

36.6 (2.6) |

59.5 (15.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 25.2 (−3.8) |

28.8 (−1.8) |

39.0 (3.9) |

49.7 (9.8) |

60.6 (15.9) |

70.6 (21.4) |

75.4 (24.1) |

73.8 (23.2) |

66.3 (19.1) |

54.0 (12.2) |

41.3 (5.2) |

30.5 (−0.8) |

51.3 (10.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 18.8 (−7.3) |

21.8 (−5.7) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

40.3 (4.6) |

50.6 (10.3) |

60.8 (16.0) |

66.4 (19.1) |

65.1 (18.4) |

57.1 (13.9) |

45.4 (7.4) |

34.1 (1.2) |

24.4 (−4.2) |

43.0 (6.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −4.5 (−20.3) |

0.5 (−17.5) |

11.8 (−11.2) |

25.6 (−3.6) |

36.7 (2.6) |

46.0 (7.8) |

54.5 (12.5) |

54.3 (12.4) |

41.8 (5.4) |

29.7 (−1.3) |

17.3 (−8.2) |

3.2 (−16.0) |

−8.5 (−22.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −27 (−33) |

−21 (−29) |

−12 (−24) |

7 (−14) |

27 (−3) |

35 (2) |

45 (7) |

42 (6) |

29 (−2) |

14 (−10) |

−2 (−19) |

−25 (−32) |

−27 (−33) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.99 (51) |

1.97 (50) |

2.45 (62) |

3.75 (95) |

4.49 (114) |

4.10 (104) |

3.71 (94) |

4.25 (108) |

3.19 (81) |

3.43 (87) |

2.42 (61) |

2.11 (54) |

37.86 (962) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 11.3 (29) |

10.7 (27) |

5.5 (14) |

1.3 (3.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

1.8 (4.6) |

7.6 (19) |

38.4 (98) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 6.3 (16) |

6.3 (16) |

4.0 (10) |

0.6 (1.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.5 (3.8) |

3.9 (9.9) |

9.8 (25) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.0 | 9.4 | 10.8 | 12.3 | 12.5 | 11.1 | 9.7 | 9.4 | 8.5 | 10.5 | 10.0 | 10.6 | 125.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 8.5 | 6.4 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 6.1 | 27.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72.2 | 71.6 | 69.7 | 64.9 | 64.1 | 65.6 | 68.5 | 70.7 | 71.1 | 68.6 | 72.5 | 75.5 | 69.6 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 13.6 (−10.2) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

27.1 (−2.7) |

35.8 (2.1) |

45.7 (7.6) |

55.8 (13.2) |

61.7 (16.5) |

61.0 (16.1) |

53.8 (12.1) |

41.7 (5.4) |

31.6 (−0.2) |

20.1 (−6.6) |

38.8 (3.8) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 135.8 | 136.2 | 187.0 | 215.3 | 281.9 | 311.4 | 318.4 | 283.0 | 226.6 | 193.2 | 113.3 | 106.3 | 2,508.4 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 46 | 46 | 51 | 54 | 62 | 68 | 69 | 66 | 60 | 56 | 38 | 37 | 56 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point and sun 1961–1990)[144][156][157] | |||||||||||||

| Sunshine data for Chicago | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 12.2 |

| Source: Weather Atlas[158] | |||||||||||||

Time zone

As in the rest of the state of Illinois, Chicago forms part of the Central Time Zone. The border with the Eastern Time Zone is located a short distance to the east, used in Michigan and certain parts of Indiana.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 4,470 | — | |

| 1850 | 29,963 | 570.3% | |

| 1860 | 112,172 | 274.4% | |

| 1870 | 298,977 | 166.5% | |

| 1880 | 503,185 | 68.3% | |

| 1890 | 1,099,850 | 118.6% | |

| 1900 | 1,698,575 | 54.4% | |

| 1910 | 2,185,283 | 28.7% | |

| 1920 | 2,701,705 | 23.6% | |

| 1930 | 3,376,438 | 25.0% | |

| 1940 | 3,396,808 | 0.6% | |

| 1950 | 3,620,962 | 6.6% | |

| 1960 | 3,550,404 | −1.9% | |

| 1970 | 3,366,957 | −5.2% | |

| 1980 | 3,005,072 | −10.7% | |

| 1990 | 2,783,726 | −7.4% | |

| 2000 | 2,896,016 | 4.0% | |

| 2010 | 2,695,598 | −6.9% | |

| 2020 | 2,746,388 | 1.9% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 2,664,452 | [159] | −3.0% |

| United States Census Bureau[160] 2010–2020[9] | |||

During its first hundred years, Chicago was one of the fastest-growing cities in the world. When founded in 1833, fewer than 200 people had settled on what was then the American frontier. By the time of its first census, seven years later, the population had reached over 4,000. In the forty years from 1850 to 1890, the city's population grew from slightly under 30,000 to over 1 million. At the end of the 19th century, Chicago was the fifth-largest city in the world,[161] and the largest of the cities that did not exist at the dawn of the century. Within sixty years of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, the population went from about 300,000 to over 3 million,[162] and reached its highest ever recorded population of 3.6 million for the 1950 census.

From the last two decades of the 19th century, Chicago was the destination of waves of immigrants from Ireland, Southern, Central and Eastern Europe, including Italians, Jews, Russians, Poles, Greeks, Lithuanians, Bulgarians, Albanians, Romanians, Turkish, Croatians, Serbs, Bosnians, Montenegrins and Czechs.[163][164] To these ethnic groups, the basis of the city's industrial working class, were added an additional influx of African Americans from the American South—with Chicago's black population doubling between 1910 and 1920 and doubling again between 1920 and 1930.[163] Chicago has a significant Bosnian population, many of whom arrived in the 1990s and 2000s.[165]

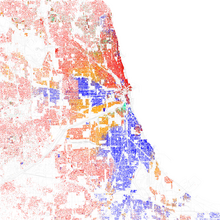

In the 1920s and 1930s, the great majority of African Americans moving to Chicago settled in a so‑called "Black Belt" on the city's South Side.[163] A large number of blacks also settled on the West Side. By 1930, two-thirds of Chicago's black population lived in sections of the city which were 90% black in racial composition.[163] Around that time, a lesser known fact about African Americans on the North Side is that the block of 4600 Winthrop Avenue in Uptown was the only block African Americans could live or open establishments.[166][167] Chicago's South Side emerged as United States second-largest urban black concentration, following New York's Harlem. In 1990, Chicago's South Side and the adjoining south suburbs constituted the largest black majority region in the entire United States.[163] Since the 1980s, Chicago has had a massive exodus of African Americans (primarily from the South and West sides) to its suburbs or outside its metropolitan area.[168] The above average crime and cost of living were leading reasons for the fast declining African American population in Chicago.[169][170][171]

Most of Chicago's foreign-born population were born in Mexico, Poland or India.[172]

Chicago's population declined in the latter half of the 20th century, from over 3.6 million in 1950 down to under 2.7 million by 2010. By the time of the official census count in 1990, it was overtaken by Los Angeles as the United States' second largest city.[173]

The city has seen a rise in population for the 2000 census and after a decrease in 2010, it rose again for the 2020 census.[174]

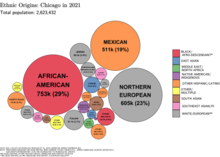

According to U.S. census estimates as of July 2019[update], Chicago's largest racial or ethnic group is non-Hispanic White at 32.8% of the population, Blacks at 30.1% and the Hispanic population at 29.0% of the population.[175][176][177][178]

| Racial composition | 2020[179] | 2010[180] | 1990[178] | 1970[178] | 1940[178] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 31.4% | 31.7% | 37.9% | 59.0%[d] | 91.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 29.8% | 28.9% | 19.6% | 7.4%[d] | 0.5% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 28.7% | 32.3% | 39.1% | 32.7% | 8.2% |

| Asian (non-Hispanic) | 6.9% | 5.4% | 3.7% | 0.9% | 0.1% |

| Two or more races (non-Hispanic) | 2.6% | 1.3% | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Race or Ethnicity |

Race Alone | Total [e] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 35.9% | 45.6% | ||

| Black or African American | 29.2% | 30.8% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino[f] | — | 29.8% | ||

| Asian | 7.0% | 8.0% | ||

| Native American | 1.3% | 2.6% | ||

| Mixed | 10.8% | — | ||

| Other | 15.8% | — | ||

Chicago has the third-largest LGBT population in the United States. In 2018, the Chicago Department of Health, estimated 7.5% of the adult population, approximately 146,000 Chicagoans, were LGBTQ.[183] In 2015, roughly 4% of the population identified as LGBT.[184][185] Since the 2013 legalization of same-sex marriage in Illinois, over 10,000 same-sex couples have wed in Cook County, a majority of them in Chicago.[186][187]

Chicago became a "de jure" sanctuary city in 2012 when Mayor Rahm Emanuel and the City Council passed the Welcoming City Ordinance.[188]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau's American Community Survey data estimates for 2022, the median income for a household in the city was $70,386,and the per capita income was $45,449. Male full-time workers had a median income of $68,870 versus $60,987 for females.[189] About 17.2% of the population lived below the poverty line.[190] In 2018, Chicago ranked seventh globally for the highest number of ultra-high-net-worth residents with roughly 3,300 residents worth more than $30 million.[191]

According to the 2022 American Community Survey, the specific ancestral groups having 10,000 or more persons in Chicago were:[192][193][194]

- Mexican (586,906)

- German (200,726)

- Irish (184,983)

- Polish (129,468)

- Italian (100,915)

- Puerto Rican (101,625)

- English (87,282)

- Chinese (67,951)

- Indian (48,535)

- Filipino (39,048)

- French (25,629)

- Russian (24,707)

- Swedish (21,795)

- Arab (19,432)

- West Indian (18,636)

- Guatemalan (18,205)

- Scottish (17,121)

- Korean (16,224)

- Ecuadorian (15,935)

- Nigerian (15,064)

- Greek (14,946)

- Norwegian (13,391)

- Colombian (13,785)

- Ukrainian (12,956)

- Vietnamese (12,280)

- Cuban (11,765)

- Czech (11,313)

- Romanian (11,237)

- Lithuanian (11,235)

- Dutch (11,196)

Persons who did not report or classify an ancestry were 548,790.

Religion

Religion in Chicago (2014)[195][196]

According to a 2014 study by the Pew Research Center, Christianity is the most prevalently practiced religion in Chicago (71%),[196] with the city being the fourth-most religious metropolis in the United States after Dallas, Atlanta and Houston.[196] Roman Catholicism and Protestantism are the largest branches (34% and 35% respectively), followed by Eastern Orthodoxy and Jehovah's Witnesses with 1% each.[195] Chicago also has a sizable non-Christian population. Non-Christian groups include Irreligious (22%), Judaism (3%), Islam (2%), Buddhism (1%) and Hinduism (1%).[195]

Chicago is the headquarters of several religious denominations, including the Evangelical Covenant Church and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. It is the seat of several dioceses. The Fourth Presbyterian Church is one of the largest Presbyterian congregations in the United States based on memberships.[197] Since the 20th century Chicago has also been the headquarters of the Assyrian Church of the East.[198] In 2014 the Catholic Church was the largest individual Christian denomination (34%), with the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago being the largest Catholic jurisdiction. Evangelical Protestantism form the largest theological Protestant branch (16%), followed by Mainline Protestants (11%), and historically Black churches (8%). Among denominational Protestant branches, Baptists formed the largest group in Chicago (10%); followed by Nondenominational (5%); Lutherans (4%); and Pentecostals (3%).[195]

Non-Christian faiths accounted for 7% of the religious population in 2014. Judaism has at least 261,000 adherents which is 3% of the population, making it the second largest religion.[199][195] A 2020 study estimated the total Jewish population of the Chicago metropolitan area, both religious and irreligious, at 319,500.[200]

The first two Parliament of the World's Religions in 1893 and 1993 were held in Chicago.[201] Many international religious leaders have visited Chicago, including Mother Teresa, the Dalai Lama[202] and Pope John Paul II in 1979.[203]

Economy

Chicago has the third-largest gross metropolitan product in the United States—about $670.5 billion according to September 2017 estimates.[204] The city has also been rated as having the most balanced economy in the United States, due to its high level of diversification.[205] The Chicago metropolitan area has the third-largest science and engineering work force of any metropolitan area in the nation.[206] Chicago was the base of commercial operations for industrialists John Crerar, John Whitfield Bunn, Richard Teller Crane, Marshall Field, John Farwell, Julius Rosenwald, and many other commercial visionaries who laid the foundation for Midwestern and global industry.

Chicago is a major world financial center, with the second-largest central business district in the United States, following Midtown Manhattan.[207] The city is the seat of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, the Bank's Seventh District. The city has major financial and futures exchanges, including the Chicago Stock Exchange, the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE), and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (the "Merc"), which is owned, along with the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT), by Chicago's CME Group. In 2017, Chicago exchanges traded 4.7 billion in derivatives.[citation needed] Chase Bank has its commercial and retail banking headquarters in Chicago's Chase Tower.[208] Academically, Chicago has been influential through the Chicago school of economics, which fielded 12 Nobel Prize winners.

The city and its surrounding metropolitan area contain the third-largest labor pool in the United States with about 4.63 million workers.[209] Illinois is home to 66 Fortune 1000 companies, including those in Chicago.[210] The city of Chicago also hosts 12 Fortune Global 500 companies and 17 Financial Times 500 companies. The city claims three Dow 30 companies: aerospace giant Boeing, which moved its headquarters from Seattle to the Chicago Loop in 2001;[211] McDonald's; and Walgreens Boots Alliance.[212] For six consecutive years from 2013 through 2018, Chicago was ranked the nation's top metropolitan area for corporate relocations.[213] However, three Fortune 500 companies left Chicago in 2022, leaving the city with 35, still second to New York City.[214]

Manufacturing, printing, publishing, and food processing also play major roles in the city's economy. Several medical products and services companies are headquartered in the Chicago area, including Baxter International, Boeing, Abbott Laboratories, and the Healthcare division of General Electric. Prominent food companies based in Chicago include the world headquarters of Conagra, Ferrara Candy Company, Kraft Heinz, McDonald's, Mondelez International, and Quaker Oats.[citation needed] Chicago has been a hub of the retail sector since its early development, with Montgomery Ward, Sears, and Marshall Field's. Today the Chicago metropolitan area is the headquarters of several retailers, including Walgreens, Sears, Ace Hardware, Claire's, ULTA Beauty, and Crate & Barrel.[citation needed]

Late in the 19th century, Chicago was part of the bicycle craze, with the Western Wheel Company, which introduced stamping to the production process and significantly reduced costs,[215] while early in the 20th century, the city was part of the automobile revolution, hosting the Brass Era car builder Bugmobile, which was founded there in 1907.[216] Chicago was also the site of the Schwinn Bicycle Company.

Chicago is a major world convention destination. The city's main convention center is McCormick Place. With its four interconnected buildings, it is the largest convention center in the nation and third-largest in the world.[217] Chicago also ranks third in the U.S. (behind Las Vegas and Orlando) in number of conventions hosted annually.[218]

Chicago's minimum wage for non-tipped employees is one of the highest in the nation and reached $15 in 2021.[219][220]

Culture and contemporary life

The city's waterfront location and nightlife attracts residents and tourists alike. Over a third of the city population is concentrated in the lakefront neighborhoods from Rogers Park in the north to South Shore in the south.[221] The city has many upscale dining establishments as well as many ethnic restaurant districts. These districts include the Mexican American neighborhoods, such as Pilsen along 18th street, and La Villita along 26th Street; the Puerto Rican enclave of Paseo Boricua in the Humboldt Park neighborhood; Greektown, along South Halsted Street, immediately west of downtown;[222] Little Italy, along Taylor Street; Chinatown in Armour Square; Polish Patches in West Town; Little Seoul in Albany Park around Lawrence Avenue; Little Vietnam near Broadway in Uptown; and the Desi area, along Devon Avenue in West Ridge.[223]

Downtown is the center of Chicago's financial, cultural, governmental, and commercial institutions and the site of Grant Park and many of the city's skyscrapers. Many of the city's financial institutions, such as the CBOT and the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, are located within a section of downtown called "The Loop", which is an eight-block by five-block area of city streets that is encircled by elevated rail tracks. The term "The Loop" is largely used by locals to refer to the entire downtown area as well. The central area includes the Near North Side, the Near South Side, and the Near West Side, as well as the Loop. These areas contribute famous skyscrapers, abundant restaurants, shopping, museums, Soldier Field, convention facilities, parkland, and beaches.[citation needed]

Lincoln Park contains the Lincoln Park Zoo and the Lincoln Park Conservatory. The River North Gallery District features the nation's largest concentration of contemporary art galleries outside of New York City.[citation needed] Lake View is home to Boystown, the city's large LGBT nightlife and culture center. The Chicago Pride Parade, held the last Sunday in June, is one of the world's largest with over a million people in attendance.[224] North Halsted Street is the main thoroughfare of Boystown.[225]

The South Side neighborhood of Hyde Park is the home of former U.S. President Barack Obama. It also contains the University of Chicago, ranked one of the world's top ten universities,[226] and the Museum of Science and Industry. The 6-mile (9.7 km) long Burnham Park stretches along the waterfront of the South Side. Two of the city's largest parks are also located on this side of the city: Jackson Park, bordering the waterfront, hosted the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893, and is the site of the aforementioned museum; and slightly west sits Washington Park. The two parks themselves are connected by a wide strip of parkland called the Midway Plaisance, running adjacent to the University of Chicago. The South Side hosts one of the city's largest parades, the annual African American Bud Billiken Parade and Picnic, which travels through Bronzeville to Washington Park. Ford Motor Company has an automobile assembly plant on the South Side in Hegewisch, and most of the facilities of the Port of Chicago are also on the South Side.[citation needed]

The West Side holds the Garfield Park Conservatory, one of the largest collections of tropical plants in any U.S. city. Prominent Latino cultural attractions found here include Humboldt Park's Institute of Puerto Rican Arts and Culture and the annual Puerto Rican People's Parade, as well as the National Museum of Mexican Art and St. Adalbert's Church in Pilsen. The Near West Side holds the University of Illinois at Chicago and was once home to Oprah Winfrey's Harpo Studios, the site of which has been rebuilt as the global headquarters of McDonald's.[citation needed]

The city's distinctive accent, made famous by its use in classic films like The Blues Brothers and television programs like the Saturday Night Live skit "Bill Swerski's Superfans", is an advanced form of Inland Northern American English. This dialect can also be found in other cities bordering the Great Lakes such as Cleveland, Milwaukee, Detroit, and Rochester, New York, and most prominently features a rearrangement of certain vowel sounds, such as the short 'a' sound as in "cat," which can sound more like "kyet" to outsiders. The accent remains well associated with the city.[227]

Entertainment and the arts

Renowned Chicago theater companies include the Goodman Theatre in the Loop; the Steppenwolf Theatre Company and Victory Gardens Theater in Lincoln Park; and the Chicago Shakespeare Theater at Navy Pier. Broadway In Chicago offers Broadway-style entertainment at five theaters: the Nederlander Theatre, CIBC Theatre, Cadillac Palace Theatre, Auditorium Building of Roosevelt University, and Broadway Playhouse at Water Tower Place. Polish language productions for Chicago's large Polish speaking population can be seen at the historic Gateway Theatre in Jefferson Park. Since 1968, the Joseph Jefferson Awards are given annually to acknowledge excellence in theater in the Chicago area. Chicago's theater community spawned modern improvisational theater, and includes the prominent groups The Second City and I.O. (formerly ImprovOlympic).[citation needed]

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) performs at Symphony Center, and is recognized as one of the best orchestras in the world.[228] Also performing regularly at Symphony Center is the Chicago Sinfonietta, a more diverse and multicultural counterpart to the CSO. In the summer, many outdoor concerts are given in Grant Park and Millennium Park. Ravinia Festival, located 25 miles (40 km) north of Chicago, is the summer home of the CSO, and is a favorite destination for many Chicagoans. The Civic Opera House is home to the Lyric Opera of Chicago.[229] The Lithuanian Opera Company of Chicago was founded by Lithuanian Chicagoans in 1956,[230] and presents operas in Lithuanian.

The Joffrey Ballet and Chicago Festival Ballet perform in various venues, including the Harris Theater in Millennium Park. Chicago has several other contemporary and jazz dance troupes, such as the Hubbard Street Dance Chicago and Chicago Dance Crash.[citation needed]

Other live-music genre which are part of the city's cultural heritage include Chicago blues, Chicago soul, jazz, and gospel. The city is the birthplace of house music (a popular form of electronic dance music) and industrial music, and is the site of an influential hip hop scene. In the 1980s and 90s, the city was the global center for house and industrial music, two forms of music created in Chicago, as well as being popular for alternative rock, punk, and new wave. The city has been a center for rave culture, since the 1980s. A flourishing independent rock music culture brought forth Chicago indie. Annual festivals feature various acts, such as Lollapalooza and the Pitchfork Music Festival.[citation needed] Lollapalooza originated in Chicago in 1991 and at first travelled to many cities, but as of 2005 its home has been Chicago.[231] A 2007 report on the Chicago music industry by the University of Chicago Cultural Policy Center ranked Chicago third among metropolitan U.S. areas in "size of music industry" and fourth among all U.S. cities in "number of concerts and performances".[232]

Chicago has a distinctive fine art tradition. For much of the twentieth century, it nurtured a strong style of figurative surrealism, as in the works of Ivan Albright and Ed Paschke. In 1968 and 1969, members of the Chicago Imagists, such as Roger Brown, Leon Golub, Robert Lostutter, Jim Nutt, and Barbara Rossi produced bizarre representational paintings. Henry Darger is one of the most celebrated figures of outsider art.[233]

Tourism

In 2014[update], Chicago attracted 50.17 million domestic leisure travelers, 11.09 million domestic business travelers and 1.308 million overseas visitors.[234] These visitors contributed more than US$13.7 billion to Chicago's economy.[234] Upscale shopping along the Magnificent Mile and State Street, thousands of restaurants, as well as Chicago's eminent architecture, continue to draw tourists. The city is the United States' third-largest convention destination. A 2017 study by Walk Score ranked Chicago the sixth-most walkable of fifty largest cities in the United States.[235] Most conventions are held at McCormick Place, just south of Soldier Field. Navy Pier, located just east of Streeterville, is 3,000 ft (910 m) long and houses retail stores, restaurants, museums, exhibition halls and auditoriums. Chicago was the first city in the world to ever erect a Ferris wheel. The Willis Tower (formerly named Sears Tower) is a popular destination for tourists.[236]

Museums

Among the city's museums are the Adler Planetarium & Astronomy Museum, the Field Museum of Natural History, and the Shedd Aquarium. The Museum Campus joins the southern section of Grant Park, which includes the renowned Art Institute of Chicago. Buckingham Fountain anchors the downtown park along the lakefront. The University of Chicago's Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, West Asia & North Africa has an extensive collection of ancient Egyptian and Near Eastern archaeological artifacts. Other museums and galleries in Chicago include the Chicago History Museum, the Driehaus Museum, the DuSable Museum of African American History, the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum, the Polish Museum of America, the Museum of Broadcast Communications, the Pritzker Military Library, the Chicago Architecture Foundation, and the Museum of Science and Industry.[citation needed]

Cuisine

Chicago lays claim to a large number of regional specialties that reflect the city's ethnic and working-class roots. Included among these are its nationally renowned deep-dish pizza; this style is said to have originated at Pizzeria Uno.[237] The Chicago-style thin crust is also popular in the city.[238] Certain Chicago pizza favorites include Lou Malnati's and Giordano's.[239]

The Chicago-style hot dog, typically an all-beef hot dog, is loaded with an array of toppings that often includes pickle relish, yellow mustard, pickled sport peppers, tomato wedges, dill pickle spear and topped off with celery salt on a poppy seed bun.[240] Enthusiasts of the Chicago-style hot dog frown upon the use of ketchup as a garnish, but may prefer to add giardiniera.[241][242][243]

A distinctly Chicago sandwich, the Italian beef sandwich is thinly sliced beef simmered in au jus and served on an Italian roll with sweet peppers or spicy giardiniera. A popular modification is the Combo—an Italian beef sandwich with the addition of an Italian sausage. The Maxwell Street Polish is a grilled or deep-fried kielbasa—on a hot dog roll, topped with grilled onions, yellow mustard, and hot sport peppers.[244]

Chicken Vesuvio is roasted bone-in chicken cooked in oil and garlic next to garlicky oven-roasted potato wedges and a sprinkling of green peas. The Puerto Rican-influenced jibarito is a sandwich made with flattened, fried green plantains instead of bread. The mother-in-law is a tamale topped with chili and served on a hot dog bun.[245] The tradition of serving the Greek dish saganaki while aflame has its origins in Chicago's Greek community.[246] The appetizer, which consists of a square of fried cheese, is doused with Metaxa and flambéed table-side.[247] Chicago-style barbecue features hardwood smoked rib tips and hot links which were traditionally cooked in an aquarium smoker, a Chicago invention.[248] Annual festivals feature various Chicago signature dishes, such as Taste of Chicago and the Chicago Food Truck Festival.[249]

One of the world's most decorated restaurants and a recipient of three Michelin stars, Alinea is located in Chicago. Well-known chefs who have had restaurants in Chicago include: Charlie Trotter, Rick Tramonto, Grant Achatz, and Rick Bayless. In 2003, Robb Report named Chicago the country's "most exceptional dining destination".[250]

Literature

Chicago literature finds its roots in the city's tradition of lucid, direct journalism, lending to a strong tradition of social realism. In the Encyclopedia of Chicago, Northwestern University Professor Bill Savage describes Chicago fiction as prose which tries to "capture the essence of the city, its spaces and its people." The challenge for early writers was that Chicago was a frontier outpost that transformed into a global metropolis in the span of two generations. Narrative fiction of that time, much of it in the style of "high-flown romance" and "genteel realism", needed a new approach to describe the urban social, political, and economic conditions of Chicago.[251] Nonetheless, Chicagoans worked hard to create a literary tradition that would stand the test of time,[252] and create a "city of feeling" out of concrete, steel, vast lake, and open prairie.[253] Much notable Chicago fiction focuses on the city itself, with social criticism keeping exultation in check.

At least three short periods in the history of Chicago have had a lasting influence on American literature.[254] These include from the time of the Great Chicago Fire to about 1900, what became known as the Chicago Literary Renaissance in the 1910s and early 1920s, and the period of the Great Depression through the 1940s.

What would become the influential Poetry magazine was founded in 1912 by Harriet Monroe, who was working as an art critic for the Chicago Tribune. The magazine discovered such poets as Gwendolyn Brooks, James Merrill, and John Ashbery.[255] T. S. Eliot's first professionally published poem, "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock", was first published by Poetry. Contributors have included Ezra Pound, William Butler Yeats, William Carlos Williams, Langston Hughes, and Carl Sandburg, among others. The magazine was instrumental in launching the Imagist and Objectivist poetic movements. From the 1950s through 1970s, American poetry continued to evolve in Chicago.[256] In the 1980s, a modern form of poetry performance began in Chicago, the poetry slam.[257]

Sports

The city has two Major League Baseball (MLB) teams: the Chicago Cubs of the National League play in Wrigley Field on the North Side; and the Chicago White Sox of the American League play in Guaranteed Rate Field on the South Side. The two teams have faced each other in a World Series only once, in 1906.[258]

The Cubs are the oldest Major League Baseball team to have never changed their city;[259] they have played in Chicago since 1871.[260] They had the dubious honor of having the longest championship drought in American professional sports, failing to win a World Series between 1908 and 2016. The White Sox have played on the South Side continuously since 1901. They have won three World Series titles (1906, 1917, 2005) and six American League pennants, including the first in 1901.

The Chicago Bears, one of the last two remaining charter members of the National Football League (NFL), have won nine NFL Championships, including the 1985 Super Bowl XX. The Bears play their home games at Soldier Field.

The Chicago Bulls of the National Basketball Association (NBA) is one of the most recognized basketball teams in the world.[261] During the 1990s, with Michael Jordan leading them, the Bulls won six NBA championships in eight seasons.[262][263]

The Chicago Blackhawks of the National Hockey League (NHL) began play in 1926, and are one of the "Original Six" teams of the NHL. The Blackhawks have won six Stanley Cups, including in 2010, 2013, and 2015. Both the Bulls and the Blackhawks play at the United Center.[264]

| Club | League | Sport | Venue | Attendance | Founded | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicago Bears | NFL | Football | Soldier Field | 61,142 | 1919 | 9 Championships (1 Super Bowl) |

| Chicago Cubs | MLB | Baseball | Wrigley Field | 41,649 | 1870 | 3 World Series |

| Chicago White Sox | MLB | Baseball | Guaranteed Rate Field | 40,615 | 1900 | 3 World Series |

| Chicago Blackhawks | NHL | Ice hockey | United Center | 21,653 | 1926 | 6 Stanley Cups |

| Chicago Bulls | NBA | Basketball | 20,776 | 1966 | 6 NBA Championships | |

| Chicago Fire | MLS | Soccer | Soldier Field | 17,383 | 1997 | 1 MLS Cup, 1 Supporters Shield |

| Chicago Sky | WNBA | Basketball | Wintrust Arena | 10,387 | 2006 | 1 WNBA Championships |

| Chicago Red Stars | NWSL | Soccer | SeatGeek Stadium | 5,863 | 2013 | 1 WPSL Elite championship |

Chicago Fire FC is a member of Major League Soccer (MLS) and plays at Soldier Field. The Fire have won one league title and four U.S. Open Cups, since their founding in 1997. In 1994, the United States hosted a successful FIFA World Cup with games played at Soldier Field.[265]

The Chicago Red Stars are a team in the National Women's Soccer League (NWSL). They previously played in Women's Professional Soccer (WPS), of which they were a founding member, before joining the NWSL in 2013. They play at SeatGeek Stadium in Bridgeview, Illinois.

The Chicago Sky is a professional basketball team playing in the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA). They play home games at the Wintrust Arena. The team was founded before the 2006 WNBA season began.[266]

The Chicago Marathon has been held each year since 1977 except for 1987, when a half marathon was run in its place. The Chicago Marathon is one of six World Marathon Majors.[267]

Five area colleges play in Division I conferences: two from major conferences—the DePaul Blue Demons (Big East Conference) and the Northwestern Wildcats (Big Ten Conference)—and three from other D1 conferences—the Chicago State Cougars (Northeast Conference); the Loyola Ramblers (Atlantic 10 Conference); and the UIC Flames (Missouri Valley Conference).[268]

Chicago has also entered into esports with the creation of the Chicago Huntsmen, a professional Call of Duty team that participates within the CDL.[citation needed]

Parks and greenspace

When Chicago was incorporated in 1837, it chose the motto Urbs in Horto, a Latin phrase which means "City in a Garden". Today, the Chicago Park District consists of more than 570 parks with over 8,000 acres (3,200 ha) of municipal parkland. There are 31 sand beaches, a plethora of museums, two world-class conservatories, and 50 nature areas.[269] Lincoln Park, the largest of the city's parks, covers 1,200 acres (490 ha) and has over 20 million visitors each year, making it third in the number of visitors after Central Park in New York City, and the National Mall and Memorial Parks in Washington, D.C.[270]

There is a historic boulevard system,[271] a network of wide, tree-lined boulevards which connect a number of Chicago parks.[272] The boulevards and the parks were authorized by the Illinois legislature in 1869.[273] A number of Chicago neighborhoods emerged along these roadways in the 19th century.[272] The building of the boulevard system continued intermittently until 1942. It includes nineteen boulevards, eight parks, and six squares, along twenty-six miles of interconnected streets.[274] The Chicago Park Boulevard System Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2018.[275][276]

With berths for more than 6,000 boats, the Chicago Park District operates the nation's largest municipal harbor system.[277] In addition to ongoing beautification and renewal projects for the existing parks, a number of new parks have been added in recent years, such as the Ping Tom Memorial Park in Chinatown, DuSable Park on the Near North Side, and most notably, Millennium Park, which is in the northwestern corner of one of Chicago's oldest parks, Grant Park in the Chicago Loop.[citation needed]

The wealth of greenspace afforded by Chicago's parks is further augmented by the Cook County Forest Preserves, a network of open spaces containing forest, prairie, wetland, streams, and lakes that are set aside as natural areas which lie along the city's outskirts,[278] including both the Chicago Botanic Garden in Glencoe and the Brookfield Zoo in Brookfield.[279] Washington Park is also one of the city's biggest parks; covering nearly 400 acres (160 ha). The park is listed on the National Register of Historic Places listings in South Side Chicago.[280]

Law and government

Government

The government of the City of Chicago is divided into executive and legislative branches. The mayor of Chicago is the chief executive, elected by general election for a term of four years, with no term limits. The current mayor is Brandon Johnson. The mayor appoints commissioners and other officials who oversee the various departments. As well as the mayor, Chicago's clerk and treasurer are also elected citywide. The City Council is the legislative branch and is made up of 50 alderpersons, one elected from each ward in the city.[281] The council takes official action through the passage of ordinances and resolutions and approves the city budget.[282]

The Chicago Police Department provides law enforcement and the Chicago Fire Department provides fire suppression and emergency medical services for the city and its residents. Civil and criminal law cases are heard in the Cook County Circuit Court of the State of Illinois court system, or in the Northern District of Illinois, in the federal system. In the state court, the public prosecutor is the Illinois state's attorney; in the Federal court it is the United States attorney.

Politics

| Year | Democratic | Republican | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 82.5% 944,735 | 15.8% 181,234 | 1.6% 18,772 |

| 2016 | 82.9% 912,945 | 12.3% 135,320 | 4.8% 53,262 |

During much of the last half of the 19th century, Chicago's politics were dominated by a growing Democratic Party organization. During the 1880s and 1890s, Chicago had a powerful radical tradition with large and highly organized socialist, anarchist and labor organizations.[284] For much of the 20th century, Chicago has been among the largest and most reliable Democratic strongholds in the United States; with Chicago's Democratic vote the state of Illinois has been "solid blue" in presidential elections since 1992. Even before then, it was not unheard of for Republican presidential candidates to win handily in downstate Illinois, only to lose statewide due to large Democratic margins in Chicago. The citizens of Chicago have not elected a Republican mayor since 1927, when William Thompson was voted into office. The strength of the party in the city is partly a consequence of Illinois state politics, where the Republicans have come to represent rural and farm concerns while the Democrats support urban issues such as Chicago's public school funding.[citation needed]

Chicago contains less than 25% of the state's population, but it is split between eight of Illinois' 17 districts in the United States House of Representatives. All eight of the city's representatives are Democrats; only two Republicans have represented a significant portion of the city since 1973, for one term each: Robert P. Hanrahan from 1973 to 1975, and Michael Patrick Flanagan from 1995 to 1997.[citation needed]

Machine politics persisted in Chicago after the decline of similar machines in other large U.S. cities.[285] During much of that time, the city administration found opposition mainly from a liberal "independent" faction of the Democratic Party. The independents finally gained control of city government in 1983 with the election of Harold Washington (in office 1983–1987). From 1989 until May 16, 2011, Chicago was under the leadership of its longest-serving mayor, Richard M. Daley, the son of Richard J. Daley. Because of the dominance of the Democratic Party in Chicago, the Democratic primary vote held in the spring is generally more significant than the general elections in November for U.S. House and Illinois State seats. The aldermanic, mayoral, and other city offices are filled through nonpartisan elections with runoffs as needed.[286]

The city is home of former United States President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama; Barack Obama was formerly a state legislator representing Chicago and later a U.S. senator. The Obamas' residence is located near the University of Chicago in Kenwood on the city's south side.[287]

Crime

Chicago's crime rate in 2020 was 3,926 per 100,000 people.[288] Chicago experienced major rises in violent crime in the 1920s, in the late 1960s, and in the 2020s.[289][290] Chicago's biggest criminal justice challenges have changed little over the last 50 years, and statistically reside with homicide, armed robbery, gang violence, and aggravated battery. Chicago has a higher murder rate than the larger cities of New York and Los Angeles. However, while it has a large absolute number of crimes due to its size, Chicago is not among the top-25 most violent cities in the United States.[291][292]

Murder rates in Chicago vary greatly depending on the neighborhood in question.[293] The neighborhoods of Englewood on the South Side, and Austin on the West side, for example, have homicide rates that are ten times higher than other parts of the city.[294] Chicago has an estimated population of over 100,000 active gang members from nearly 60 factions.[295][296] According to reports in 2013, "most of Chicago's violent crime comes from gangs trying to maintain control of drug-selling territories,"[297] and is specifically related to the activities of the Sinaloa Cartel, which is active in several American cities.[298] Violent crime rates vary significantly by area of the city, with more economically developed areas having low rates, but other sections have much higher rates of crime.[297] In 2013, the violent crime rate was 910 per 100,000 people;[299] the murder rate was 10.4 per 100,000 – while high crime districts saw 38.9 murders, low crime districts saw 2.5 murders per 100,000.[300]