Summit, Illinois

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2010) |

Summit, Illinois | |

|---|---|

| Village of Summit | |

Cement silos in Summit | |

| Motto(s): Strength, Unity, Progress | |

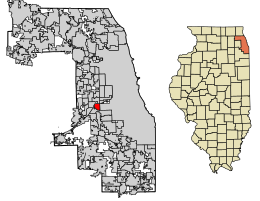

Location of Summit in Cook County, Illinois. | |

Location of Illinois in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 41°47′N 87°49′W / 41.783°N 87.817°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Cook |

| Founded | 1890 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Sergio Rodriguez |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.26 sq mi (5.85 km2) |

| • Land | 2.12 sq mi (5.49 km2) |

| • Water | 0.14 sq mi (0.36 km2) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 11,161 |

| • Density | 5,267.11/sq mi (2,033.86/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Code(s) | 60501 |

| Area code | 708 |

| FIPS code | 17-73638 |

| Wikimedia Commons | Summit, Illinois |

| Website | www |

Summit is a city in Cook County, Illinois, United States. The population was 11,161 at the 2020 census.[2] The name Summit, in use since 1836, refers to the highest point on the Chicago Portage between the northeast-flowing Chicago River and the southwest-flowing Des Plaines River located just north of the city.

Argo is a subdivision annexed by Summit in 1911 when it was new. Named for the nearby cornstarch and baking powder manufacturing plant, it developed separately from the older part of the city. The name "Argo" is still widely used but is not part of the name of the city itself.

Geography

According to the 2010 census, Summit has a total area of 2.257 square miles (5.85 km2), of which 2.12 square miles (5.49 km2) (or 93.93%) is land and 0.137 square miles (0.35 km2) (or 6.07%) is water.[3] Most of Summit is in the floodplain of the Des Plaines River.[4]

History

The area around Summit has been hunted and traveled through for 12,000 years but only continuously occupied since 900CE. When Europeans first arrived the area was inhabited or used by the Meskwaki, Illini, Miami, Sauk, and Chippewa-Ottawa-Potawatomi tribes.[5][6]

In 1673 the Marquette-Joliet expedition arrived at the portage north of the city and went on to the location of Chicago. At that time the importance of a portage was noted. A local trading network developed from that time until the Native Americans were removed beginning in 1816.[7][8]

Surveyed in 1821, in 1830 land was for sale by the Illinois and Michigan Canal Commission. There may have been a tavern at "Summit Ford" in 1832, by 1835 there was a sub-divided settlement with a tavern, blacksmith shop, and stagecoach stop. "Summit Corners" was where westbound Archer Ave. turned south and Lyons-Summit Rd. (now approximately Lawndale Ave.) went west. Chicago politician "Long John" Wentworth bought much of the surrounding area and used it for farming.[9][10]

Between 1836 and 1848 the Illinois and Michigan Canal was built through the subdivision. Most of the canal workers were Irish laborers and many were able to buy property with their canal script pay.[11]

In 1850 gravel and clay pits were opened in the area for local use. After 1865 limestone quarries north of the canal provided jobs into the 1920s, when they were closed, often used as garbage dumps, then covered over. Today's Hanover Park is a filled gravel and clay pit.[12]

In 1856 the Joliet and Chicago Railroad (Chicago and Alton Railroad in 1862) built a line along the south bank of the canal. Today this is Metra's Heritage Corridor commuter line.[13][14]

In 1890 Summit was incorporated as a city. When John Wentworth, and his political influence, died in 1888 his heirs and the settlement residents feared being annexed by Chicago. The settlement was re-platted much as it is today, with Center St. going north from Archer Ave. and Lincoln St./Lawndale Ave. going northwest from Center St. over the canal. This area was changed with the construction of Interstate 55, which effectively replaced Lawndale Ave. with the Illinois Route 171 ramp. A housing complex was at the site of the 1836 settlement.[15]

Between 1892 and 1900 the Chicago Sanitary Canal was built. It was just north of the Illinois and Michigan Canal but was much larger. In 1899 a large center-pier swing steel bridge was built for Lawndale Ave., the only crossing for miles in either direction until the 1920s. In 1900 the Chicago Sanitary Canal opened and replaced the Illinois and Michigan Canal, which was abandoned. In Summit the old canal was filled in 1974.[16][17]

In 1901 the Chicago and Joliet Electric Railway Interurban was operating a double-track line down Archer Ave. To the east it connected with Chicago streetcars at Cicero Ave. (then the city limits), to the southwest it went past Argo and on to Joliet. A branch went north on Lawndale Ave to Ogden Ave. in Lyons. In 1933 the rail-cars were replaced with buses.[18][19]

In 1907 Corn Products Corp. (now Ingredion) began construction of the world's largest corn-processing plant south of Summit (Bedford Park today) in 1907. At the same time two properties, north and south of 63rd St., were sub-divided as a "company town" type neighborhood called "Argo" after the factory. In 1911 Summit annexed Argo but its separation by the Indiana Harbor Belt Railroad tracks at 59th St., dependence on the factory, and separate business district along 63rd St. with Chicago streetcar (later bus) service made it develop as a separate community. The name "Argo" is still in widespread use in both the public and private sectors.[20]

Between 1910 and 1920 the population of Summit more than tripled, from 949 to 4,019, and increased again to 6,548 in 1930. The nature of the city changed from rural to industrial, largely because of the Corn Products plant. Farms in the old section were sub-divided and the new Argo area was annexed into the city. In addition to Corn Products other industries went up west of Archer Rd. and the large rail yard south of the city created a large number of jobs.[21][22]

The city was overwhelmed with the increase and public services were not able to keep up. Water supply was a major problem, and schools were severely over-crowded. Between 1910 and 1930 three elementary, one high, and two Catholic schools were opened.[23]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 272 | — | |

| 1900 | 547 | — | |

| 1910 | 949 | 73.5% | |

| 1920 | 4,019 | 323.5% | |

| 1930 | 6,548 | 62.9% | |

| 1940 | 7,043 | 7.6% | |

| 1950 | 8,957 | 27.2% | |

| 1960 | 10,374 | 15.8% | |

| 1970 | 11,569 | 11.5% | |

| 1980 | 10,110 | −12.6% | |

| 1990 | 9,971 | −1.4% | |

| 2000 | 10,637 | 6.7% | |

| 2010 | 11,054 | 3.9% | |

| 2020 | 11,161 | 1.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[22] | |||

As of the 2020 census[24] there were 11,161 people, 3,269 households, and 2,536 families residing in the city. The population density was 4,945.06 inhabitants per square mile (1,909.30/km2). There were 3,789 housing units at an average density of 1,678.78 per square mile (648.18/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 26.83% White, 7.88% African American, 2.48% Native American, 2.02% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 37.32% from other races, and 23.44% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 72.75% of the population.

There were 3,269 households, out of which 48.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.03% were married couples living together, 22.15% had a female householder with no husband present, and 22.42% were non-families. 20.71% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.37% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.92 and the average family size was 3.41.

The city's age distribution consisted of 30.3% under the age of 18, 9.3% from 18 to 24, 28% from 25 to 44, 20% from 45 to 64, and 12.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32.3 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 106.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $46,972, and the median income for a family was $53,000. Males had a median income of $33,532 versus $26,804 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,911. About 15.9% of families and 17.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 26.2% of those under age 18 and 8.0% of those age 65 or over.

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2010[25] | Pop 2020[26] | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 2,662 | 1,791 | 24.1% | 16.0% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 1,011 | 852 | 9.1% | 7.6% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 28 | 21 | 0.3% | 0.2% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 199 | 222 | 1.8% | 2.0% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 0 | 3 | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 3 | 37 | 0.0% | 0.3% |

| Mixed Race/Multi-Racial (NH) | 109 | 115 | 1.0% | 1.0% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 7,042 | 8,120 | 63.7% | 72.8% |

| Total | 11,054 | 11,161 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Public education

Elementary and middle school students attend Cook County School District 104 schools, and then move on to Argo Community High School District 217.

Business and industry

Ingredion operates a corn milling and processing plant at 65th Street and Archer Avenue, in an area known as Argo. This facility is one of the largest of its kind in the world.[27]

ACH Food Companies operates a manufacturing and processing plant here for Mazola corn oil, Karo corn syrup and Argo Baking Powder and Corn Starch.

The Institute for Food Safety and Health (formerly the National Center for Food Safety and Technology) is in Bedford Park, adjacent to the Ingredion facility. It is affiliated with the Illinois Institute of Technology and the Food and Drug Administration's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition.[28]

Frito-Lay has a zone office in Summit. Summit has also been the home of the Desplaines Valley News newspaper since 1913.

Transportation

Summit's multimodal transportation network encompasses the following:

- The Stevenson Expressway (Interstate 55) runs through the northwest side of the city.

- The Tri-State Tollway (Interstate 294) is 3 miles (5 km) to the southwest.

- Chicago Midway International Airport is approximately three miles to the east.

- Argo Crossing Rail Junction - Indiana Harbor Belt Railroad/CSX and Canadian National Railway/Union Pacific Railroad – is located along the southwest boundary of the city.

- Summit (Amtrak station) and Metra Heritage Corridor

- Chicago Transit Authority and Pace buses

- Illinois and Michigan Canal

Notable people

- John Garklāvs, archbishop of the Orthodox Church in America, keeper of the Tchvin Icon of the Mother of Our God.[29]

- Fred Hampton, Black Panther Party

- Ted Kluszewski, first baseman, member of the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame[30]

- Clayton Lambert, pitcher for the Reds

- Sheldon Mallory, outfielder for the Oakland Athletics

- Emmett Till, lived in Argo with his mother until he was nine, when they moved to Detroit.[31]

- "Long John" Wentworth, former mayor of Chicago, retired to a farm on land part of which later became part of Summit

References

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Summit village, Illinois". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ "G001 - Geographic Identifiers - 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

- ^ Summit, Illinois. City-Data.com. Accessed April 15, 2012.

- ^ Genzen, Jonathan (2007). The Chicago River, A History in Photographs. Westcliffe. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-56579-553-2.

- ^ Kott, Robert (2009). Summit. Arcadia. pp. 8–9, 17. ISBN 978-0-7385-5248-4.

- ^ Genzen (2007), pp. 12–13.

- ^ Kott (2009), pp. 9, 12.

- ^ Genzen (2007), pp. 24–25.

- ^ Kott (2009), pp. 9, 31, 33–35, 38, 58.

- ^ Kott (2009), pp. 7, 33, 36, 60.

- ^ Kott (2009), pp. 17, 21–22, 33, 34, 60.

- ^ Kott (2009), pp. 36, 62.

- ^ "Heritage Corridor (HC) line map". Metra. 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ Kott (2009), pp. 35, 39, 58, 118.

- ^ Genzen (2007), pp. 38–43, 59.

- ^ Kott (2009), pp. 57, 59, 61.

- ^ Central Electric Railfans' Association Bulletin 99. C.E.R.A. 1956. pp. 11–12, 23.

- ^ Kott (2009), pp. 64, 98.

- ^ Kott (2009), pp. 69–72.

- ^ Kott (2009), p. 69.

- ^ a b "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ Kott (2009), pp. 83–87.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data – Summit village, Illinois". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data – Summit village, Illinois". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "News Release - Investors - Ingredion Incorporated". Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ "About". IIT IFSH. Illinois Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on June 28, 2013. Retrieved March 21, 2014.

- ^ "John Garklavs". The New York Times. April 14, 1982.

- ^ "Reds Hall of Fame and Museum". Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ "How Emmett Till's Death and Open Casket Spurred Civil Rights Activism". Retrieved November 7, 2016.