Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt

Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1189 BC–1077 BC | |||||||||

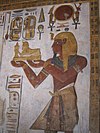

Portrait of Ramesses IX from his tomb KV6. | |||||||||

| Capital | Pi-Ramesses | ||||||||

| Common languages | Egyptian language | ||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Egyptian Religion | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||

| Historical era | New Kingdom of Egypt | ||||||||

• Established | 1189 BC | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1077 BC | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Periods and dynasties of ancient Egypt |

|---|

|

All years are BC |

The Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XX, alternatively 20th Dynasty or Dynasty 20) is the third and last dynasty of the Ancient Egyptian New Kingdom period, lasting from 1189 BC to 1077 BC. The 19th and 20th Dynasties together constitute an era known as the Ramesside period owing to the predominance of rulers with the given name "Ramesses". This dynasty is generally considered to mark the beginning of the decline of Ancient Egypt at the transition from the Late Bronze to Iron Age. During the period of the Twentieth Dynasty, Ancient Egypt faced the crisis of invasions by Sea Peoples. The dynasty successfully defended Egypt, while sustaining heavy damage.

History

After the death of the last pharaoh of the 19th Dynasty, Queen Twosret, Egypt entered into a period of civil war. Because of lost historical records, the cause of the civil war is unknown. The war was ended with the accession to the throne by Setnakhte, who founded the 20th Dynasty of Egypt.

From the reign of Setnakhte and his son Ramesses III, Egypt faced the crisis caused by the invading of the Sea Peoples. These invasions formed part of a series of linked crises in numerous Mediterranean civilizations. Together, these crises are often referred to as the Late Bronze Age collapse.

The Sea Peoples caused considerable damage to the people of Egypt, visible in the historical record. One inscription reads:

"All at once the lands were removed and scattered in the fray. No land could resist their arms, from Hatti, Kode, Carchemish, Arzawa, and Alashiya on – being cut off at one time. A camp was set up in Amurru. They desolated its people and its land was like that which had never existed. They were coming forward toward Egypt, while the flame was prepared for them."

Not only Egypt was affected by the Sea People invasions. The empire of the Hittites, a long-standing rival to Egypt, collapsed, never to rise again. (In the inscription quoted above, the Hittites are called "Hatti".)

With the victory in the Battle of Djahy and the Battle of the Delta during Year 8 of Ramesses III's reign, Egypt successfully repelled the invading Sea Peoples, protecting Egypt from ruin like other Bronze Age civilizations. During the Twentieth Dynasty, many of the temples were built to display the power of Egypt. However, they also indicate the political ascendancy of the priesthood over the pharaoh.

The Twentieth Dynasty declined because of drastic climate change, infighting in the royal family, and growing power of the priesthood and nobility. Following the death of Ramesses XI, the last pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty, a period of chaos ensued. This was ended by Smendes, a member of the Egyptian nobility, who became the first Pharaoh of the 21st Dynasty.

Background

Upon the death of the last pharaoh of the 19th Dynasty, Queen Twosret, Egypt descended into a period of civil war, as attested by the Elephantine stela built by Setnakhte. The circumstances of Twosret's demise are uncertain, as she may have died peacefully during her reign or been overthrown by Setnakhte, who was likely already middle aged at the time.[2]

20th Dynasty

A consistent theme of this dynasty was the loss of pharaonic power to the High Priests of Amun. Horemheb, a pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty, had restored the traditional Ancient Egyptian religion and the priesthood of Amun after their abandonment by Akhenaten. With the High Priests now acting as intermediaries between the gods and the people, rather than the pharaoh, the position of pharaoh no longer commanded the same kind of power as it had in the past.[3]

Setnakhte

Setnakhte stabilized the situation in Egypt, and may have driven off an attempted invasion by the Sea Peoples. He ruled for about 3-4 years before being succeeded by his son Ramesses III.

Ramesses III

In Year 5 of his reign, Ramesses defeated a Libyan invasion of Egypt by the Libu, Meshwesh and Seped people through Marmarica, who had previously unsuccessfully invaded during the reign of Merneptah.[4]

Ramesses III is most famous for decisively defeating a confederacy of the Sea Peoples, including the Denyen, Tjekker, Peleset, Shardana and Weshesh in the Battle of Djahy and the Battle of the Delta during Year 8 of his reign. Within the Papyrus Harris I, which attests these events in detail, Ramesses is said to have settled the defeated Sea Peoples in "strongholds", most likely located in Canaan, as his subjects.[3][5]

In Year 11 of Ramesses' reign, another coalition of Libyan invaders was defeated in Egypt.

Between regnal Year 12 and Year 29, a systematic program of reorganization of the varied cults of the Ancient Egyptian religion was undertaken, by creating and funding new cults and restoring temples.

In Year 29 of Ramesses' reign, the first recorded labor strike in human history took place, after food rations for the favored and elite royal tomb builders and artisans in the village of Set Maat (now known as Deir el-Medina), could not be provisioned.[6]

The reign of Ramesses III is also known for a harem conspiracy in which Queen Tiye, one of his lesser wives, was implicated in an assassination attempt against the king, with the goal of putting her son Pentawer on the throne. The coup was unsuccessful. The king died from the attempt on his life; however, it was his legitimate heir and son Ramesses IV who succeeded him to the throne, who thereafter arrested and put approximately 30 conspirators to death.[7][8]

Ramesses IV

At the start of his reign Ramesses IV started an enormous building program on the scale of Ramesses the Great's own projects. He doubled the number of work gangs at Set Maat to a total of 120 men and dispatched numerous expeditions to the stone quarries of Wadi Hammamat and the turquoise mines of the Sinai. One of the largest expeditions included 8,368 men, of which some 2,000 were soldiers.[9] Ramesses expanded his father's Temple of Khonsu at Karnak and possibly began his own mortuary temple at a site near the Temple of Hatshepsut. Another smaller temple is associated with Ramesses north of Medinet Habu.

Ramesses IV saw issues with the provision of food rations to his workmen, similar to the situation under his father. Ramessesnakht, the High Priest of Amun at the time, began to accompany state officials as they went to pay the workmen their rations, suggesting that, at least in part, it was the Temple of Amun and not the Egyptian state that was responsible for their wages.[citation needed]

He also produced the Papyrus Harris I, the longest known papyrus from Ancient Egypt, measuring in at 41 meters long with 1,500 lines of text to celebrate the achievements of his father.

Ramesses V

Ramesses V reigned for no more than 4 years, dying of smallpox in 1143 BC. The Turin Papyrus Cat. 2044 attests that during his reign the workmen of Set Maat were forced to periodically stop working on Ramesses' KV9 tomb out of "fear of the enemy", suggesting increasing instability in Egypt and an inability to defend the country from what are presumed to be Libyan raiding parties.[10]

The Wilbour Papyrus is thought to date from Ramesses V's reign. The document reveals that most of the land in Egypt by that point was controlled by the Temple of Amun, and that the Temple had complete control over Egypt's finances.[11]

Ramesses VI

Ramesses VI is best known for his tomb which, when built, inadvertently buried the tomb of pharaoh Tutankhamun underneath, keeping it safe from grave robbing until its discovery by Howard Carter in 1922.

Ramesses VII

Ramesses VII's only monument is his tomb, KV1.[citation needed]

Ramesses VIII

Almost nothing is known about Ramesses VIII's reign, which lasted for a single year. He is only attested at Medinet Habu and through a few plaques. The only monument from his reign is his modest tomb, which was used for Mentuherkhepeshef, son of Ramesses IX, rather than Ramesses VIII himself.[citation needed]

Ramesses IX

During Year 16 and Year 17 of Ramesses IX's reign famous tomb robbery trials took place, as attested by the Abbott Papyrus. A careful examination by a vizierial commission was undertaken of ten royal tombs, four tombs of the Chantresses of the Estate of the Divine Adoratrix, and finally the tombs of the citizens of Thebes. Many of these were found to have been broken into, like the tomb of Pharaoh Sobekemsaf II, whose mummy had been stolen.[12]

Ramesses IX's cartouche has been found at Gezer in Canaan, suggesting that Egypt at this time still had some degree of influence in the region.[13]

Most of the building projects during Ramesses IX's reign were at Heliopolis.[14]

Ramesses X

Ramesses X's reign is poorly documented. The Necropolis Journal of Set Maat records the general idleness of the workmen at this time, due, at least in part, to the danger of Libyan raiders.[15]

Ramesses XI

Ramesses XI was the last pharaoh of the 20th Dynasty. During his reign the position grew so weak that in the south the High Priests of Amun at Thebes became the de facto rulers of Upper Egypt, while Smendes controlled Lower Egypt even before Ramesses XI's death. Smendes would eventually found the Twenty-First dynasty at Tanis.[16]

Decline

As happened under the earlier Nineteenth Dynasty, this dynasty struggled under the effects of the bickering between the heirs of Ramesses III. For instance, three different sons of Ramesses III are known to have assumed power as Ramesses IV, Ramesses VI and Ramesses VIII respectively. However, at this time Egypt was also increasingly beset by a series of droughts, below-normal flooding levels of the Nile, famine, civil unrest and official corruption – all of which would limit the managerial abilities of any king.

Sea Peoples in Egypt

The late 13th century BC was a time of uncertainty and conflict for peoples and polities of the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean due to the invasion by Sea Peoples, which caused the Late Bronze Age collapse.[17][18] While there is not much information left to show us why the Sea Peoples began the large scale invasion, the written evidence shows the weakening of central administrations, erosion of political powers, and food shortage might be the reasons.[19]

From Ramses III's mortuary temple at Medinet Habou depicting a chaotic scene of boats and warriors entwined in battle in the Nile delta, it showing that Sea Peoples were seaborne foes from different origins.[20] They launched a combined land-sea invasion that destabilized the already weakened power base of empires and kingdoms of the old world, and attempted to enter or control the Egyptian territory.[17]

While with the victory in the Battle of Djahy and the Battle of the Delta during Year 8 of Ramesses III's reign, Egypt successfully repelled the invading forces of Sea Peoples, the damage that caused the collapse of the Eastern Mediterranean world also damaged the trade routes of Egypt, as most of their trading partners had been destroyed by Sea Peoples.

Pharaohs of the 20th Dynasty

The pharaohs of the 20th Dynasty ruled for approximately 120 years: from c. 1187 to 1064 BC. The dates and names in the table are mostly taken from "Chronological Table for the Dynastic Period" in Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss & David Warburton (editors), Ancient Egyptian Chronology (Handbook of Oriental Studies), Brill, 2006. Many of the pharaohs were buried in the Valley of the Kings in Thebes (designated KV). More information can be found on the Theban Mapping Project website.[21]

| Pharaoh | Image | Prenomen (Throne Name) | Horus-name | Reign | Burial | Consort(s) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setnakhte |  |

Userkhaure-setepenre | Kanakhtwerpehty | 1189 – 1186 BC | KV14 | Tiy-merenese | May have usurped the throne from his predecessor, Twosret. |

| Ramesses III |  |

Usermaatre-Meryamun | Kanakhtaanesyt | 1186 – 1155 BC | KV11 | Iset Ta-Hemdjert Tyti Tiye |

|

| Ramesses IV |  |

Usermaatre Setepenamun, later Heqamaatre Setepenamun | Kanakhtankhemmaat | 1155 – 1149 BC | KV2 | Duatentopet | |

| Ramesses V / Amenhirkhepeshef I |  |

Usermaatre Sekheperenre | Kanakhtmenmaat | 1149 – 1145 BC | KV9 | Henutwati Tawerettenru |

|

| Ramesses VI / Amenhirkhepeshef II |  |

Nebmaatre Meryamun | Kanakhtaanakhtu | 1145 – 1137 BC | KV9 | Nubkhesbed | |

| Ramesses VII / Itamun |  |

Usermaatre Setepenre Meryamun | Kanakhtanemnesu | 1136 – 1129 BC | KV1 | ||

| Ramesses VIII / Sethhirkhepeshef |  |

Usermaatre-Akhenamun | (unknown) | 1130 – 1129 BC | |||

| Ramesses IX / Khaemwaset I |  |

Neferkare Setepenre | Kanakhtkhaemwaset | 1129 – 1111 BC | KV6 | Baketwernel | |

| Ramesses X / Amenhirkhepeshef III |  |

Khepermaatre Setepenre | Kanakhtsekhaenre | 1111 – 1107 BC | KV18 | ||

| Ramesses XI / Khaemwaset II |  |

Menmaatre Setpenptah | Kanakhtmeryre | 1107 – 1077 BC | KV4 | Tentamun |

Timeline

Pharaonic Family tree

The Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt was the last of the New Kingdom of Egypt. The familial relationships are unclear, especially towards the end of the dynasty.

Gallery

-

Ramesses III was the son of Sethnakht. During his reign, he fought off the invasions of the Sea Peoples in Egypt and tolerated their settlement in Canaan. A conspiracy was hatched to kill him, but it failed. He was later murdered. His mummy, long an inspiration for the scary Hollywood films, showed his throat was slit.

-

Ramesses IV was the fifth son of Ramesses III. He assumed the throne after his four older brothers had died.

-

Ramesses V was the son of Ramesses IV and Queen Duatentopet. During his reign Libyan raiders attacked the country and attempted to conquer Thebes, forcing the workers of Deir el-Medina to halt work in the Valley of the Kings. He died of smallpox.

-

Ramesses VI was an uncle of Ramesses V. He usurped his predecessor's throne and later his tomb, KV9.

-

Ramesses VII was the son of Ramesses VI. During his reign, prices of grain soared to the highest levels. His mummy has never been found but cups bearing his name were found in the royal cache at Deir el-Bahri. He was buried in KV1.

-

Ramesses VIII, born Sethherkhepeshef, was a brother of Ramesses VI and a surviving son of Ramesses III. He may have ruled for a year or two. His tomb has never been identified.

-

Ramesses IX was the grandson of Ramesses III, nephew of Ramesses IV and VI, and a son of Mentuherkhepeshef, who never became a pharaoh.

-

Ramesses X, born Amunherkhepeshef, took the throne after Ramesses IX. He is a poorly documented king, with few monuments to his name. His tomb, KV18, was left unfinished.

-

Ramesses XI was the last pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty. As Egypt weakened, Ramesses XI was forced to share power in a triumvirate with Herihor, the high priest of Amun, and Smendes, governor of Lower Egypt. Ramesses XI was buried in Lower Egypt by Smendes, who later took the throne himself.

See also

Pharaoh is a historical novel by Bolesław Prus, set in Egypt at the end of the Twentieth Dynasty, which adds two fictional rulers: Ramesses XII and Ramesses XIII. It has been adapted into a film of the same title.

References

- ^ "The Mystery of the Sea Peoples | Classical Wisdom Weekly". classicalwisdom.com. Retrieved 2024-03-18.

- ^ Hartwig Altenmüller, "The Tomb of Tausert and Setnakht," in Valley of the Kings, ed. Kent R. Weeks (New York: Friedman/Fairfax Publishers, 2001), pp.222-31

- ^ a b "New Kingdom of Egypt". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- ^ Grandet, Pierre (2014-10-30). "Early–mid 20th dynasty". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. 1 (1): 4.

- ^ Lorenz, Megaera. "The Papyrus Harris". fontes.lstc.edu. Archived from the original on 2017-01-15. Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- ^ William F. Edgerton, The Strikes in Ramses III's Twenty-Ninth Year, JNES 10, No. 3 (July 1951), pp. 137-145

- ^ Dodson and Hilton, pg 184

- ^ Grandet, Pierre (2014-10-30). "Early–mid 20th dynasty". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. 1 (1): 5–8.

- ^ Jacobus Van Dijk, 'The Amarna Period and the later New Kingdom' in The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, ed. Ian Shaw, Oxford University Press paperback, (2002), pp.306-307

- ^ A.J. Peden, The Reign of Ramesses IV, (Aris & Phillips Ltd: 1994), p.21 Peden's source on these recorded disturbances is KRI, VI, 340-343

- ^ Alan H. Gardiner, R. O. Faulkner: The Wilbour Papyrus. 4 Bände, Oxford University Press, Oxford 1941-52.

- ^ Une enquête judiciaire à Thèbes au temps de la XXe dynastie : ...Maspero, G. (Gaston), 1846-1916.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel (January 2007). "Is the Philistine Paradigm Still Viable?": 517.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Nicolas Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt, Blackwell Books, 1992. p.289

- ^ E.F. Wente & C.C. Van Siclen, "A Chronology of the New Kingdom" in Studies in Honor of George R. Hughes, (SAOC 39) 1976, p.261

- ^ Dodson and Hilton, pg 185-186

- ^ a b Kaniewski, David; Van Campo, Elise; Van Lerberghe, Karel; Boiy, Tom; Vansteenhuyse, Klaas; Jans, Greta; Nys, Karin; Weiss, Harvey; Morhange, Christophe; Otto, Thierry; Bretschneider, Joachim (8 June 2011). "The Sea Peoples, from Cuneiform Tablets to Carbon Dating". PLOS ONE. 6 (6): e20232. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...620232K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020232. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3110627. PMID 21687714.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ Ward WA, Sharp Joukowsky M. (1992). The Crisis years: the 12th century BC: from beyond the Danube to the Tigris.

- ^ Kaniewski D. (2010). "Late Second-Early First Millennium BC abrupt climate changes in coastal Syria and their possible significance for the history of the Eastern Mediterranean". Quaternary Research. 74 (2): 207. Bibcode:2010QuRes..74..207K. doi:10.1016/j.yqres.2010.07.010.

- ^ Roberts RG. Identity, choice, and the Year 8 reliefs of Ramesses III at Medinet Habou.

- ^ Sites in the Valley of the Kings