Battle of Djahy

| Battle of Djahy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Egyptian-Sea People wars | |||||||

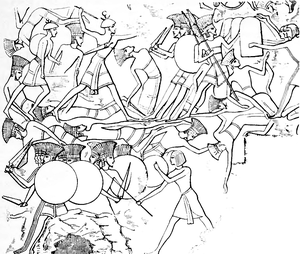

Sea Peoples in conflict with the Egyptians in the battle of Djahy | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| New Kingdom of Egypt | Sea Peoples | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Ramesses III | Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Many killed, and captured | ||||||

The Battle of Djahy was a major land battle between the forces of Pharaoh Ramesses III and the Sea Peoples who intended to invade and conquer Egypt. The conflict occurred on the Egyptian Empire's easternmost frontier in Djahy, or modern-day southern Lebanon, in the eighth year of Ramesses III or about c. 1178 BC.

In this battle the Egyptians, led by Ramesses III, defeated the Sea Peoples, who were attempting to invade Egypt by land and sea. Almost all that is known about the battle comes from the mortuary temple of Ramesses III in Medinet Habu. The description of the battle and prisoners is documented in detail on the temple's walls, which also contain the longest hieroglyphic inscription known. Temple reliefs feature many bound prisoners defeated in battle.

Historical background

The battle occurred during the Bronze Age collapse, a prolonged period of region-wide droughts, crop failures, depopulation, invasions, and collapse of urban centers. It is likely that the Nile-irrigated lands remained fruitful and would have been highly desirable to Egypt's neighbors. During this chaotic time, a new group of people from the north, the Sea Peoples, attacked and plundered various Near Eastern powers.

Ramesses III had previously defeated an attack by the Libyans on the Egyptian Empire's western frontier, in his fifth year (1181 B.C.E.). Many 12th century BC civilizations were destroyed by the Sea Peoples and other migrating nations. The Hittite Empire fell, as did the Mycenaean civilization, the kingdom of Alashiya (which consisted of part or all of Cyprus) and Ugarit, and other cultures.

The Sea Peoples moved around the eastern Mediterranean, attacking the coasts of Anatolia, Cyprus, Syria and Canaan, before attempting an invasion of Egypt in the 1180s. They were described as great warriors, and some evidence suggests they had a high level of organization and military strategy. Egypt was in particular danger because the invaders did not merely want the spoils and goods of the land, but the land itself; and Egypt had good soils and access to gold. The Egyptians say that no other country had withstood their attacks, as these inscriptions from the mortuary temple of Ramesses III in Medinet Habu attest:

The foreign countries (i.e. Sea Peoples) made a conspiracy in their islands. All at once the lands were removed and scattered in the fray. No land could stand before their arms: from Hatti, Qode, Carchemish, Arzawa and Alashiya on, being cut off (i.e. destroyed) at one time. A camp was set up in Amurru. They desolated its people, and its land was like that which has never come into being. They were coming forward toward Egypt, while the flame was prepared before them. Their confederation was the Peleset, Tjeker, Shekelesh, Denyen and Weshesh, lands united. They laid their hands upon the land as far as the circuit of the earth, their hearts confident and trusting: 'Our plans will succeed![2]

Battle

Prior to the battle, the Sea Peoples had sacked the Hittite vassal state of Amurru which was located close to the border of the Egyptian Empire. This gave Ramesses III time to prepare for the expected invasion. As he states in an inscription from his mortuary temple at Medinet Habu: "I equipped my frontier in Zahi (Djahy) prepared before them."[3] The Hittitologist Trevor Bryce writes that the Sea Peoples' "land forces were moving south along the Levantine coast and through Palestine when they were confronted and stopped by Ramesses' forces at the Egyptian frontier in Djahy in the region of later Phoenicia".[4]

Ramesses III refers to his battle with the Sea Peoples in stark, uncompromising terms:

The [Egyptian] charioteers were warriors [...], and all good officers, ready of hand. Their horses were quivering in their every limb, ready to crush the [foreign] countries under their feet...Those who reached my boundary, their seed is not; their heart and soul are finished forever and ever.[5]

Aftermath

While the battle ended with an Egyptian victory, Egypt's war with the Sea Peoples was not yet over. The Sea Peoples would attack Egypt proper with their naval fleet, around the mouth of the Nile river. These invaders were defeated in the Battle of the Delta during which many were either killed by Egyptian archers, or dragged from their boats and killed on the banks of the Nile river by Ramesses III's army.

Despite the military victories, Egypt could not ultimately prevent them from settling in the eastern parts of their empire decades later. With this conflict, and a subsequent second battle with invading Libyan tribes in Year 11 of Ramesses III, Egypt's treasury was depleted and the empire would never fully recover. The Egyptian Empire over Asia and Nubia would be permanently lost less than 80 years after Ramesses III's reign under Ramesses XI, the last king of Egypt's New Kingdom.

Reliefs depicting the battle

Egyptian reliefs depicting the battle in the mortuary temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu provide much of the information regarding the battle. Featured are Egyptian troops, chariots and auxiliaries fighting an enemy that also employed chariots, very similar in design to Egyptian ones.

References

- ^ Gary Beckman, "Hittite Chronology", Akkadica, 120 (2000). p.23 The exact date of the battle is unknown and depends on whether Amenmesse had an independent reign over all Egypt or if it was subsumed within the reign of Seti II. However, a difference of 3 years is minor.

- ^ Medinet Habu inscription of Ramesses III's 8th year (1178 B.C.E.), lines 16-17, trans. by John A. Wilson in Pritchard, J.B. (ed.) Ancient Near Eastern Texts relating to the Old Testament, 3rd edition, Princeton 1969., p.262

- ^ Extracts from Medinet Habu inscription, trans. James H. Breasted 1906, iv.§§ 65-66

- ^ Trevor R. Bryce, The Kingdom of the Hittites, sub-chapter 'The Fall of the Kingdom and its Aftermath', Oxford University Press, 1998. p.371

- ^ Breasted, op. cit., pp.65-66