J. K. Rowling

J. K. Rowling | |

|---|---|

Rowling in 2010 | |

| Born | Joanne Rowling 31 July 1965 Yate, Gloucestershire, England |

| Pen name |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Alma mater | University of Exeter Moray House |

| Period | 1997–present |

| Genre | |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Signature | |

| |

| Website | |

| jkrowling | |

Joanne Rowling, CH, OBE, HonFRSE, FRCPE, FRSL (/ˈroʊlɪŋ/ ROH-ling;[1] born 31 July 1965), known by her pen name J. K. Rowling, is a British author, philanthropist, film producer, and screenwriter. She is the author of the Harry Potter series, which has won multiple awards and sold more than 500 million copies as of 2018,[2] and became the best-selling book children's series in history in 2008.[3] The books are the basis of a popular film series. She also writes crime fiction under the pen name Robert Galbraith.

Born in Yate, Gloucestershire, Rowling was working as a researcher and bilingual secretary for Amnesty International in 1990 when she conceived the idea for the Harry Potter series while on a delayed train from Manchester to London. The seven-year period that followed saw the death of her mother, birth of her first child, divorce from her first husband, and relative poverty until the first novel in the series, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, was published in 1997. There were six sequels, of which the last was released in 2007. Since then, Rowling has written several books for adult readers: The Casual Vacancy (2012) and—under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith—the crime fiction Cormoran Strike series. In 2020, her "political fairytale" for children, The Ickabog, was released in instalments in an online version.[4]

Rowling has progressed from living on benefits to being named the world's first billionaire author by Forbes.[5] Rowling disputed the assertion, saying she was not a billionaire.[6] Forbes reported that she lost her billionaire status after giving away much of her earnings to charity.[7] Her UK sales total in excess of £238 million, making her the best-selling living author in Britain.[8] The 2021 Sunday Times Rich List estimated Rowling's fortune at £820 million, ranking her as the 196th richest person in the UK.[9] Rowling was appointed a member of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH) in the 2017 Birthday Honours for services to literature and philanthropy. She established the Volant Charitable Trust to support at-risk women, children and young people and has supported multiple charities, including Comic Relief, Gingerbread, and multiple sclerosis (MS) and coronavirus disease 2019 causes as well as launching her own charity, Lumos.

Time named her a runner-up for its 2007 Person of the Year, noting the social, moral, and political inspiration she has given her fans.[10] In October 2010, she was named the "Most Influential Woman in Britain" by leading magazine editors.[11] Rowling has voiced views on UK politics, especially in opposition to Scottish independence and Brexit, and has been critical of her relationship with the press. Since late 2019, she has publicly expressed her opinions on transgender people and related civil rights. These have been criticised as transphobic by LGBT rights organisations and some feminists, but have received support from other feminists and individuals.

Name

Although she writes under the pen name J. K. Rowling, before her remarriage her name was Joanne Rowling,[12] or Jo.[13][14] Staff at Bloomsbury Publishing asked that she use two initials rather than her full name, anticipating that young boys—their target audience—would not want to read a book written by a woman.[12][15] As she had no middle name, she chose K (for Kathleen) as the second initial of her pen name, from her paternal grandmother.[12] Following her 2001 remarriage,[16] she has sometimes used the name Joanne Murray when conducting personal business.[17][18] During the Leveson Inquiry into the practices and ethics of the British press, she gave evidence under the name of Joanne Kathleen Rowling[19] and her entry in Who's Who lists her name also as Joanne Kathleen Rowling.[20]

Life and career

Early life and education

Joanne Rowling was born on 31 July 1965 at Cottage Hospital in Yate.[21][22][a] At birth, she had no middle name.[25][26] Joanne's parents were Anne (née Volant), a science technician, and Peter James Rowling, a Rolls-Royce engineer.[27][28] They first met on a train departing from King's Cross Station bound for Arbroath in 1964.[29] They married on 14 March 1965.[29] Rowling's sister Dianne was born two years after Joanne.[29]

The family moved to the nearby village of Winterbourne on the northern fringe of Bristol when Rowling was four.[30] Rowling enrolled at St Michael's Primary School in Winterbourne when she was five.[31][32][b] The family moved again, to the Gloucestershire village of Tutshill, close to Chepstow, Wales, when she was about nine,[35] where they purchased the historic Church Cottage,[c] which was next door to St. Luke's Church, and 20 yards (18 m) from the Church of England school Rowling would attend beginning in 1974.[37] Parker writes in The New Yorker that the other Rowling family members were not regular churchgoers, but that "Rowling regularly attended services in the church next door".[27] Biographer Smith writes that the Rowling sisters "never attended Sunday school or services" despite the church's proximity.[38]

When she was a young teenager, Rowling's great-aunt gave her Hons and Rebels, the autobiography of civil rights activist Jessica Mitford.[39] Mitford became Rowling's heroine, and she read all her books.[40] Rowling has said that her teenage years were unhappy.[27] Her home life was complicated by her mother's diagnosis with multiple sclerosis (MS)[41] and a strained relationship with her father, with whom she is not on speaking terms.[27] She stated in 2020 that her father would have preferred a son, and described herself as having severe obsessive–compulsive disorder in her teens.[42] She later said that Hermione Granger was a "caricature" of herself when she was eleven.[43]

Her secondary school was Wyedean School and College, where her mother worked in the science department.[44] Sean Harris, her best friend in the Upper Sixth, owned a turquoise Ford Anglia which she says inspired a flying version that appeared in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.[45] Like many teenagers, she became interested in rock music, listening to the Clash,[46] the Smiths, and Siouxsie Sioux, adopting the look of the latter with back-combed hair and black eyeliner, a look that she still sported when beginning university.[29] Steve Eddy, her first secondary school English teacher, remembers her as "not exceptional" but "one of a group of girls who were bright, and quite good at English".[27] Rowling took A-levels in English, French and German, achieving two As and a B[29] and was head girl.[27]

Rowling earned a BA in French and classics at the University of Exeter.[47][48] Martin Sorrell, a French professor at Exeter, remembers "a quietly competent student, with a denim jacket and dark hair, who, in academic terms, gave the appearance of doing what was necessary".[27] Rowling recalls doing little work, preferring to read Dickens and Tolkien.[27] After a year of study in Paris, she graduated from Exeter in 1986.[27]

Inspiration and single parenthood

Rowling worked as a researcher and bilingual secretary in London for Amnesty International,[49] then moved with her boyfriend to Manchester[50] where she worked at the Chamber of Commerce.[29] In 1990, she was on a four-hour delayed train trip from Manchester to London when the characters Harry Potter, Ron Weasley, and Hermione Granger "came fully formed" into her mind.[21][51] When she reached her Clapham Junction flat, she began to write.[52]

In December[citation needed] 1990, Rowling's mother Anne died after suffering from MS for ten years.[21] Rowling was writing Harry Potter at the time and had never told her mother about it.[18] Her mother's death heavily affected Rowling's writing.[18]

An advertisement in The Guardian led Rowling to move to Porto, Portugal, to teach English as a foreign language.[29][40] As she taught in the evenings, she wrote during the day, initially while listening to Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto.[27] After 18 months in Porto, she met the Portuguese television journalist Jorge Arantes in a bar and found that they shared an interest in Jane Austen.[29] They married on 16 October 1992, and their daughter Jessica Isabel Rowling Arantes was born on 27 July 1993 in Portugal.[29][d] Rowling had miscarried in the past.[29]

Rowling and Arantes separated on 17 November 1993.[29] Biographers have suggested that Rowling suffered domestic abuse during her marriage,[29][54] which she later confirmed.[55] Arantes stated in an article for The Sun in June 2020 that he had slapped her and did not regret it.[56]

In December[citation needed] 1993, with three chapters of Harry Potter in her suitcase,[27] Rowling and her daughter moved to Edinburgh, Scotland, to be near her sister.[21]

Seven years after graduating from university, Rowling saw herself as a failure.[57] Her marriage had failed, and she was jobless with a dependent child, but she described her failure as "liberating" and allowing her to focus on writing.[57] In her 20s, she contemplated suicide.[58] A depression she experienced shortly after her daughter's birth inspired the Dementors, soul-sucking creatures introduced in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban.[59] She signed up for welfare benefits, describing her economic status as being "poor as it is possible to be in modern Britain, without being homeless".[27][57]

Arantes arrived in Scotland in March 1994 seeking both Rowling and their daughter.[29] She obtained an order of restraint against him and filed for divorce in August; Arantes later returned to Portugal.[29] She began a teacher training course in August 1995 at Moray House School of Education, part of the University of Edinburgh,[60] after completing her first novel while living on benefits.[61] She often wrote in cafés, including one owned by her brother-in-law.[62][63]

Harry Potter

Synopsis

Harry Potter is a wizard who lives with the Dursleys, his aunt and uncle. The Dursleys are not wizards—they are Muggles, the wizards' term for non-wizards[64]—but they know magic exists and are opposed to it. On Harry's eleventh birthday, Rubeus Hagrid brings him a letter inviting him to attend Hogwarts.[65] The seven-book series chronicles Harry's seven years at Hogwarts and his adventures with friends Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley.[64] The series begins with Philosopher's Stone, in which Harry foils Lord Voldemort's plan to acquire an elixir of life. Voldemort is Harry's nemesis; his failed attempt to kill Harry as a baby gave Harry his lightning-shaped scar.[66][64] It ends with Deathly Hallows, in which Voldemort is finally killed after Harry destroys his horcruxes: magical objects that preserve a person's life by storing a portion of their soul.[64]

The Harry Potter novels portray two distinct worlds: the Muggle world and the wizards' world. Although they sometimes intermingle, these worlds are separate. Wizards use magic instead of technology and inhabit a world populated with legendary creatures and characterized by motifs drawn from British history. Muggles live in a world like the contemporary world.[67][68] The literary scholar Suman Gupta adds a third world: the reader's world.[69]

Publication history

Rowling finished the manuscript for Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, which she wrote on a typewriter, by June 1995.[70] Following an enthusiastic report from Bryony Evans, an early reader,[71] Christopher Little Literary Agency agreed to represent Rowling. Philosopher's Stone was submitted to twelve publishers, all of which rejected the manuscript.[29] Barry Cunningham, who ran the children's literature department at Bloomsbury Publishing, eventually bought the manuscript and gave Rowling a £1,500 advance.[29][72][73] Nigel Newton, who headed Bloomsbury at the time, decided to go ahead with the manuscript after his eight-year-old daughter finished one chapter and wanted to keep reading.[74] Although Bloomsbury agreed to publish the book, Cunningham says that he advised Rowling to get a day job, since she had little chance of making money in children's books.[75] In June 1997, Bloomsbury published Philosopher's Stone with an initial print run of 500 copies.[76][77] Rowling received grants in 1996 and 1997 from the Scottish Arts Council to support writing Philosopher's Stone and Chamber of Secrets, respectively.[78][79]

Scholastic Corporation bought the American rights to Philosopher's Stone for US$105,000 at the Bologna Children's Book Fair in April 1997.[80] Arthur A. Levine, who ran the imprint at Scholastic that published the first book, pushed for a name change. He argued for Harry Potter and the School of Magic and Rowling suggested Sorcerer's Stone as a "compromise".[81] She bought an apartment in Edinburgh using money from the sale to Scholastic.[82]

Scholastic published Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone in September 1998.[83] It was not widely reviewed, but publications that did review Sorcerer's Stone spoke well of it.[84] Sorcerer's Stone became a New York Times bestseller by December.[85] Chamber of Secrets followed in July 1998. In December 1999, the third novel, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, won the Nestlé Smarties Book Prize, making Rowling the first person to win the award three times running.[86]

The last four Harry Potter books—Goblet of Fire, Order of the Phoenix, Half-Blood Prince, and Deathly Hallows—each set records as the fastest-selling books in history.[87][88][89][additional citation(s) needed] The series, totalling 4,195 pages,[90] has been translated, in whole or in part, into 65 languages.[91] As of February 2018[update], it had sold more than 500 million copies.[2]

Harry Potter films

Around October 1998, Warner Bros. purchased film rights to the first two novels for a "seven-figure sum".[92] David Heyman managed the sale.[93] Rowling turned down Warner Bros.'s original offer, mainly because it did not prevent Warner Bros. from making Harry Potter films that were not based on her novels.[94] The studio eventually agreed to include such a clause and Rowling sold Warner Bros. an 18-month option to produce films based on the books.[95]

Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, an adaptation of the first Harry Potter book, was released in November 2001.[96] The film series concluded with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, which was adapted in two parts; part one was released on 19 November 2010 and part two followed on 15 July 2011.[97][98] At the 2011 British Academy Film Awards, Rowling, producers David Heyman and David Barron, along with directors David Yates, Mike Newell, and Alfonso Cuarón, collected the Michael Balcon Award for Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema for the Harry Potter film franchise.[99]

Steve Kloves wrote the screenplays for all but the fifth film.[100] Rowling assisted him in the writing process, ensuring that his scripts did not contradict future Harry Potter novels.[101] She also reviewed all the scripts[102][additional citation(s) needed] and was a producer on the final two-part instalment, Deathly Hallows.[103][additional citation(s) needed] She stipulated that cast members should come only from the UK or Ireland;[104] the films have adhered to that rule.[105] She also requested that Coca-Cola, which won rights to tie in its products to the film series, donate to charity and run ads celebrating reading.[106][107]

In September 2013, Warner Bros. announced an "expanded creative partnership" with Rowling, based on a planned series of films about her character Newt Scamander, author of Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them. The first film, set roughly 70 years before the original series, was released in November 2016.[108] In 2016, it was announced that the series would consist of five films. The second, Crimes of Grindelwald, was released in November 2018.[109] The third, Secrets of Dumbledore, is scheduled to be released on 15 April 2022.[110]

Remarriage and wealth

Rowling acquired the courtesy title of laird of Killiechassie in 2001 when she bought Killiechassie House and its surrounding estate in Perthshire, Scotland.[111][112] She married Neil Murray, a doctor and friend of her sister's,[27] in a private ceremony at Killiechassie House on 26 December 2001.[16][113] Their son, David Gordon Rowling Murray, was born in 2003,[114] and their daughter Mackenzie Jean Rowling Murray, to whom she dedicated Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, was born in 2005.[115] As of 2020, she also owns a £4.5 million Georgian house in Kensington, and a £2 milllion home in Edinburgh.[116]

In 2004, Forbes named Rowling as the first person to become a US-dollar billionaire by writing books;[117] the 2004 list included 587 billionaires, with Rohling debuting near the bottom of the list[118][119] at number 552.[120] Rowling denied that she was a billionaire.[6] By 2012, Forbes concluded that Rowling was no longer a billionaire due to high taxes in Britain and having donated an estimated $150 million as of 2012 to charities.[116][121] The 2021 Sunday Times Rich List estimated Rowling's fortune at £820 million, ranking her as the 196th-richest person in the UK.[9]

Rowling has consistently been ranked among the highest earning authors in the world.[122] She was named the world's highest paid author in 2017 and 2019 by Forbes with net earnings of £72 million ($95 million) and $92 million respectively.[123][124] Among a Forbes list of the 100 highest paid celebrities in 2018, she was number thirteen.[116]

The Casual Vacancy

In mid-2011, Rowling left Christopher Little Literary Agency, following her agent Neil Blair to the Blair Partnership. He represented her for the publication of The Casual Vacancy,[125] published on 27 September 2012 by Little, Brown and Company. It is the first book she wrote for adult readers and the first published since the end of the Harry Potter series,[126][127] Despite mixed reviews,[128] it became a bestseller in the UK within weeks of its release.[129] Casual Vacancy was made into a miniseries of three one-hour episodes, adapted by Sarah Phelps and co-created by the BBC and HBO.[130]

Cormoran Strike

In April 2013, Little Brown published The Cuckoo's Calling, the purported début novel of author Robert Galbraith.[131] The novel, a detective story in which private investigator Cormoran Strike unravels the supposed suicide of a supermodel, initially sold 1,500 copies in hardback.[132] On Twitter, a user called Jude Callegari told India Knight that "Robert Galbraith" was Rowling.[133] Richard Brooks, arts editor of The Sunday Times, eventually contacted Rowling's agent, who confirmed Galbraith was Rowling's pseudonym.[134] Rowling later said she enjoyed working as Robert Galbraith.[135] She took the name from Robert F. Kennedy, a personal hero, and Ella Galbraith, a name she had invented for herself in childhood.[136]

Within days of the revelation, sales of Cuckoo's Calling rose by 4,000%,[133] and Little Brown printed another 140,000 copies to meet demand.[137] It turned out that Judith "Jude" Callegari was the best friend of the wife of Chris Gossage, a partner at Russells Solicitors, Rowling's law firm.[138][139] Russells apologised for the leak, confirming it was not part of a marketing stunt,[137] and agreed to make a substantial charitable donation to a veteran's group, ending legal action.[140] The Silkworm, the second Cormoran Strike novel, was released in 2014.[141] Career of Evil (October 2015);[142] Lethal White (18 September 2018);[143] and Troubled Blood (September 2020) followed.[144]

In 2017, the BBC released a Cormoran Strike television series, starring Tom Burke as Cormoran Strike. The series was picked up by HBO for distribution in the United States and Canada.[145]

Later Harry Potter publications

Although Rowling stated in 2007 that she planned to write an encyclopaedia of Harry Potter's wizarding world consisting of unpublished material and notes,[146] she later said, "... I haven't started writing it. I never said it was the next thing I'd do."[147]

Rowling launched a website called Pottermore in 2011 to host Harry Potter projects and electronic downloads.[148] The site includes information on characters, places and objects in the Harry Potter universe.[149]

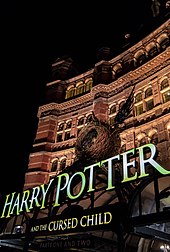

In October 2015, Rowling announced that a two-part play she had co-authored with playwrights Jack Thorne and John Tiffany, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, was the "eighth Harry Potter story" and that it would focus on the life of Harry Potter's youngest son Albus after the epilogue of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.[150] The first round of tickets sold out in several hours.[151] At Cursed Child's premiere in London, Rowling confirmed that she would not write any more Harry Potter books.[152]

Children's stories

Between 26 May 2020 and 10 July 2020, Rowling published an online children's story, The Ickabog. Rowling shelved the story that she had planned to release in 2007, previously referred to as a "political fairytale", and published it instead in daily online installments for children[4] as a response to the lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic.[153][154] Royalties from the book were donated to charities helping groups strongly impacted by COVID-19.[153][155]

Rowling's 2021 children's novel, The Christmas Pig, is unconnected to any of Rowling's previous works.[156] It received generally positive reviews and became a bestseller.[157][158][159]

Influences

Rowling describes Jane Austen as her "favourite author of all time",[160] and acknowledges Homer, Geoffrey Chaucer, and William Shakespeare as literary influences.[161] According to the critic Beatrice Groves, Harry Potter is "rooted in the Western literary tradition", including the classics.[162] Scholars agree that Harry Potter is heavily influenced by the juvenile fantasy of writers such as C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Elizabeth Goudge, Ursula K. Le Guin, Dianna Wynne Jones, and E. Nesbit.[163] As a child, Rowling read Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia, Goudge's The Little White Horse, Manxmouse by Paul Gallico, and books by E. Nesbit and Noel Streatfeild.[164] She expresses admiration for Lewis, in whose writing battles between good and evil are also prominent.[165]

Characters learn to use magic in earlier works including Le Guin's Earthsea series, which features a school of wizardry, and the Chrestomanci books by Jones.[166][167] Rowling's setting of a "school of witchcraft and wizardry" departs from the still older tradition of protagonists as apprentices to accomplished magicians, famously exemplified by The Sorcerer's Apprentice: yet this trope does appear in Harry Potter, when Harry receives individual instruction from Remus Lupin and other teachers.[168] Rowling also draws on the tradition of stories set in boarding schools, the most prominent example of which is Thomas Hughes's 1857 volume Tom Brown's School Days.[169]

Rowling has named Jessica Mitford as her greatest influence. She said "Jessica Mitford has been my heroine since I was 14 years old, when I overheard my formidable great-aunt discussing how Mitford had run away at the age of 19 to fight with the Reds in the Spanish Civil War", and claims what inspired her about Mitford was that she was "incurably and instinctively rebellious, brave, adventurous, funny and irreverent, she liked nothing better than a good fight, preferably against a pompous and hypocritical target".[39]

Critical analysis

Harry Potter series

Harry Potter has been defined as a fairy tale, a Bildungsroman, and a work about the characters' education.[170] Its overarching theme is death. Rowling admits "death and bereavement" to be "one of the central themes in all seven books".[171] Characters in Harry's life die and he must confront his own death in Deathly Hallows.[172] In Harry's world, death is not binary but mutable, a state that exists in degrees.[173] The series is fundamentally about existentialism – Harry must learn and grow into the maturity necessary to accept death. Unlike Voldemort who chose to evade death, separating and hiding his soul in seven parts, Harry's soul is whole and undamaged, nourished by friendship and love.[174]

Like death, truth is mutable in Harry's world.[175] Although he seeks truth about his family, Harry lies to others. Truth is revealed in pieces hiding greater truths within, which Harry must uncover.[176] Each book follows a similar structure in which Harry unravels increasingly painful truths.[177]

Harry Potter is a fantasy about good vs. evil.[178] It derives from the European tradition of the lost prince with intrinsic character, leadership and heroism.[178] Farah Mendlesohn writes that Harry Potter takes place in a conventional political world, reflecting liberalism in the United Kingdom,[178] which is juxtaposed with anachronisms and aristocratic traditions. Harry escapesthe loathsome suburbs for a public school, attended by aristocrats and children descended from the oldest magical families in the land,[179] where social order is imposed by the "sorting hat". The choice Harry receives from the sorting hat is extraordinary, its confusion caused by his contamination from Voldemort: he is given the choice of two destinies rather than a manifestation of free will.[180] Michiko Kakutani writes that the series is an epic about personal independence and free will.[181]

The series has been viewed as a Christian moral fable evoking the psychomachia tradition, in which stand-ins for good and evil fight for supremacy over a person's soul.[182] Like C. S. Lewis's The Chronicles of Narnia, it contains Christian symbolism and allegory. Children's literature critic Joy Farmer sees parallels between Harry and Jesus Christ,[183] writing that "magic is both authors' way of talking about spiritual reality".[171] There are numerous connections between Harry's story and that of Jesus: Harry is hidden at birth; Professor McGonagall says of him "every child in our world will know his name";[171] Dumbledore tells Harry "your father ... shows himself most plainly when you have need of him"; and Dobby says "Harry Potter shone like a beacon of hope for those of us who thought the Dark days would never end".[183] Harry carries the protection of his mother's sacrifice in his blood; Voldemort, who wants Harry's blood and the protection it carries, lacks the understanding that love vanquishes evil just as Christ's love for humanity vanquishes death.[183] Voldemort succumbed to temptation, as did Satan, and is beyond redemption.[184] Harry has divine characteristics whereas Voldemort "has quite literally risen from the dead to become a malevolent figure who seems larger than life". [185] Despite the similarities between C. S. Lewis and Rowling's work, the latter received scathing criticism, has been called "Satanic", and thought to advocate witchcraft, which Farmer believes to be a profound misreading.[186]

Rowling excels at characterizations, with simple descriptive writing.[187] The characters seldom consider the philosophical or ethical implications of their actions directly, even the intellectual Hermione Granger.[188] Moral questions are addressed through emotions rather than intellectual consideration. The critic Lakshmi Chaudhry sees this as an aspect of the series's "moral fuzziness", whereas Mary Pharr writes that the absence of moral clarity derives from Harry Potter's postmodernism – in the postmodern world, there are no moral absolutes.[189] She explains that Harry as an "epic hero for the postmodern world" fails to adhere to a moral code or religious doctrine.[175] Harry typically acts through empathy towards others despite personal risk, differentiating him from Tom Riddle who became Voldemort.[181] The same group of characters friends and enemies appear throughout the series with new characters introduced in each book, such as the new Defense of the Dark Arts teacher each year who appears in each book.[187] Snape is the antihero; Malfoy is the rival throughout the series, Ron and Hermione are Harry's best friends from the beginning.[190][e]

Harry's heroism is imbued with modern attributes such as courage and valiance and based on "sympathy and compassion".[194] Love is a dividing line between Harry and Voldemort: Harry is a hero because he loves others; Voldemort is a villain because he does not.[188] Harry reflects the archetype of the returning prince denied his heritage. In modern fantasy the hero's attributes and birthright "are played out, bit by bit, as the journey unfolds" according to Mendlesohn. The hero is shaped during the journey, but Rowling has imbued Harry with a heroic birthright and innate characteristics such as his niceness. The hero's companions possess qualities that Harry lacks; Hermione's intelligence, Ron's faithfulness, and Hagrid's kind strength.[195]

Magic enhances the ordinary, and renders everyday objects as extraordinary.[192] Eva Oppermann believes that Michel Foucault's concept of heterotopia (alternate spaces) applies to Hogwarts.[196] The magical and real worlds are parallel yet separate. Rowling lavishes attention to the smallest detail in the magical world: there are a myriad of spells and charms, owls deliver letters, photographs and paintings present live images, places such as Diagon alley, Hogwarts, Hagrid's cottage, objects such as the sorting hat and fancy wands, to give it veracity.[197] John Pennington disagrees, writing Rowling breaks the fundamental rules of fantasy by adhering too closely to the reality.[198]

Contemporary fiction

With the publication of The Casual Vacancy in 2012, Rowling showed that she cannot be identified as exclusively an author of children's books. The Casual Vacancy and the subsequent crime series published under the pen-name Robert Galbraith reflects a firm grasp of a range of genres.[199] The Casual Vacancy is a tragicomedy, promoted as a black comedy. The literary critic Ian Parker writing in The New Yorker describes it as a "rural comedy of manners".[27][200] The critic Tison Pugh and Rowling herself describe it as a contemporary version of 19th-century British fiction examining village life such as in Austen's novels and George Eliot's Middlemarch.[27][201] The five Cormoran Strike detective novels are written under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith. In the first of which was released in 2013,[202] Strike and his assistant investigate grisly murders. The killers are truly depraved according to Pugh.[203] Although an example of hardboiled detective fiction, Strike deviates from the unattached loner, as Rowling begins to build romance in the series.[204]

Reception

The Harry Potter series, particularly following the release of Prisoner of Azkaban in September 1999 and Goblet of Fire on 8 July 2000, has enjoyed enormous commercial success and attention from academic critics.[205] It was adapted into the Harry Potter film series, whose first instalment was released in 2001;[206] and its books have been translated into at least 60 languages.[207] Neither of Rowling's later works, The Casual Vacancy (2012) and the Cormoran Strike series, have been as well received as Harry Potter, though reception was positive overall.[208]

The Harry Potter series have been described as including complex and varied representations of female characters,[209] but nonetheless ultimately conforming to stereotypical and patriarchal depictions of gender.[209][210][211] The ostensible absence of gender divides in the books obscures the typecasting of female characters and traditional depictions of gender.[210] According to scholars Elizabeth Heilman and Trevor Donaldson, the subordination of female characters goes further early in the series. The final three books "showcase richer roles and more powerful females": for instance, the series' "most matriarchal character", Molly Weasley, engages substantially in the final battle of Deathly Hallows, while a number of other women are shown in positions of leadership.[209] Yet, even particularly capable female characters such as Hermione Granger and Minerva McGonagall are ultimately placed in supporting roles.[212] More generally, girls and women are more frequently depicted as emotional; more often defined by their appearance; and less often given agency in familial settings.[210][213]

Some Christian critics, particularly Evangelical Christians, have claimed that Harry Potter promotes witchcraft and are harmful to children.[214][215][216] Such criticism has taken two main forms: allegations that Harry Potter is a pagan text; and claims that it encourages children to oppose authority, derived mainly from Harry's rejection of the Dursleys, his adoptive parents.[217] In the late 1990s and early 2000s, parents in several US cities launched protests against teaching Harry Potter in schools.[218] Novels in the series, particularly Philosopher's Stone, were often banned in the US.[218] Harry Potter has had several vocal religious defenders in the US and elsewhere; Christian supporters have claimed that the books espouse Christian values or that the Bible does not prohibit the forms of magic described in the series.[219]

One current of Rowling criticism focusses on her perceived conventionalism. Harold Bloom, William Safire, and Philip Hensher have all regarded Rowling's prose as poor and her plots as conventional.[220][221] According to A. S. Byatt, Harry Potter is a simplistic work that reflects a dumbed-down culture dominated by soap operas and reality television.[170][222] Jack Zipes notes that earlier novels in the series have the same general plot. Harry begins the book with the Dursleys and escapes to begin his year at Hogwarts. There, he confronts a challenge related to Lord Voldemort, his nemesis. He succeeds by the end of the book and heads back to the Dursleys' house. According to Zipes, this repetition is "tedious and grating".[66] These critics argue that the Harry Potter books do not innovate on established literary forms, either in their language or narrative, or challenge readers' preconceived ideas.[170][223] Philip Nel rejects these criticisms as "snobbery" that reacts mainly to the novels' popularity,[220] whereas Mary Pharr argues that Harry Potter's conventionalism is the point: by amalgamating pre-existing literary forms familiar to her readers, Rowling invites them to "ponder their own ideas".[224] While acknowledging that the overarching narrative and themes in Harry Potter are not original, Julia Eccleshare suggests that Rowling's deft plot development and storytelling make the books compelling.[225]

Legacy

Harry Potter has been credited with transforming the landscape of children's literature.[226][227] Beginning in the 1970s, children's books on the market were generally realistic as opposed to fantastic;[228] in parallel, adult fantasy emerged as a popular genre due to the influence of The Lord of the Rings.[229] The next decade saw an increasing interest in grim, realist themes, with an outflow of fantasy readers and writers to adult works.[230][231] The commercial success of Harry Potter in 1997 reversed this trend.[232] The scale of its growth had no precedent in the children's market: within four years, it occupied 28% of that field by revenue.[233] Children's literature rose in cultural status,[234] and fantasy became a dominant genre therein.[235] Older works in the genre, including Diana Wynne Jones's Chrestomanci series and Diane Duane's Young Wizards, were reprinted and rose in popularity; some authors re-established their careers.[236] In the following decades, many Harry Potter imitators and subversions grew popular.[237] Harry Potter's success even led the New York Times, in June 2000, to create a separate children's bestseller list.[238] According to Levy and Mendlesohn, the list's purpose was to save adult novels from "the embarrassment of being outdone by a children's book".[239]

Rowling has described Harry Potter fandom as a "global phenomenon".[170] Critics have attributed this success to a number of factors: the nostalgia evoked by the boarding-school story, the endearing nature of Rowling's characters and the accessibility of her books to non-readers.[240][241] In Eccleshare's view, the books are "neither too literary nor too popular, too difficult nor too easy, neither too young nor too old", and hence span a broad range of readers.[242] Mendlesohn and James state that the crucial comparison is to author Enid Blyton, who also wrote in simple language about groups of children, and held a long-term sway over the British children's market. In their view, Rowling has filled Blyton's gap.[243] Some critics view this, along with the concurrent success of Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials, as part of a broader shift in reading tastes: a rejection of literary fiction in favour of plot and adventure.[244] This is reflected in the BBC's 2003 "Big Read" survey of the UK's favourite books, where Pullman and Rowling ranked at number 3 and 5, respectively, with very few British literary classics in the top 10.[245]

Harry Potter's popularity led its publishers to plan elaborate releases and spawned a textual afterlife among fans and forgers. Beginning with the release of Prisoner of Azkaban on 8 July 1999 at 3:45 pm,[246] its publishers coordinated to begin selling the books at a single time globally, introduced security protocols to prevent premature purchases, and required booksellers to sign contracts promising not to sell copies before the appointed time.[247] At the same time, knockoff Harry Potter books, copycats, and parodies emerged to capitalize on its commercial success.[248] Driven by the growth of internet access and use around its initial publication, fan fiction about the series proliferated and has spawned a diverse community of readers and writers.[249][250] While Rowling has supported fan fiction, her statements about characters – for instance, that Harry and Hermione could have been a couple, and that Dumbledore is gay – have complicated her relationship with readers.[251] According to the scholar Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, this shows that modern readers feel a sense of ownership over the text, independent of, and sometimes contradicting, authorial intent.[252]

The Harry Potter books gained recognition for the unproven assertion[253] of their potential to improve literacy by motivating children to read much more than they otherwise would.[254] Research by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) found no increase in reading among children coinciding with the Harry Potter publishing phenomenon, nor was the broader downward trend in reading among Americans arrested during the rise in the popularity of the Harry Potter books.[253][255]

Legal disputes

In the 1990s and 2000s, Rowling was both a plaintiff and defendant in lawsuits alleging copyright infringement. Nancy Stouffer sued Rowling in 1999, alleging that Harry Potter was based on stories she published in 1984.[256][257] Rowling won in September 2002.[258] Richard Posner describes Stouffer's suit as deeply flawed and notes that the court, finding she had used "forged and altered documents", assessed a $50,000 penalty against her.[259]

With her literary agents and Warner Bros., Rowling has brought legal action against publishers and writers of Harry Potter knockoffs in several countries.[260][261][262] In the mid-2000s, Rowling and her publishers obtained a series of injunctions prohibiting public readings of her books before their release dates,[263] which civil liberties and free speech campaigners criticised, claiming the "right to read".[264][265]

Beginning in 2001, after Rowling sold film rights to Warner Bros., the studio began actions to take Harry Potter fan sites offline unless it determined that they were made by "authentic" fans for innocuous purposes.[266] The Harry Potter fandom was upset and some fans created a group called Defense Against the Dark Arts to help one another respond to the studio.[267] In 2007, with Warner Bros., Rowling started proceedings to prevent a Michigan-based publisher from releasing a book based on content from a fan site called The Harry Potter Lexicon.[268][256] Rowling had named Lexicon a favourite fan site in 2004.[269] She said at trial that she had already written a Harry Potter encyclopedia.[270] The court held that the Lexicon was not a fair use of Rowling's material and did not constitute a derivative work.[271] The judgment did not close the door completely on publishing the Lexicon, however, and it eventually came out in 2009.[272]

Philanthropy

In 2000, Rowling established the Volant Charitable Trust to "work to alleviate social deprivation, with a particular emphasis on supporting women, children and young people at risk".[273] Rowling and MEP Emma Nicholson founded Lumos in 2005 (then known as the Children's High Level Group, CHLG).[274] Rowling was named president of the charity Gingerbread (originally One Parent Families) in 2004, after becoming its first ambassador in 2000.[275] Rowling was the second most generous UK donor in 2015 (following singer Elton John), giving about US$14 million through the Volant Charitable Trust and the Lumos Foundation.[276]

In social welfare, Rowling collaborated with Sarah Brown to write a book of children's stories to benefit One Parent Families.[277] To support the CHLG, in 2007 Rowling auctioned a handwritten and illustrated copy of The Tales of Beedle the Bard that sold for almost £2 million.[278][279] Rowling later published the book to benefit Lumos,[280] and in 2013, donated the proceeds of nearly £19 million (then about US$30 million) to the organisation.[281] Profits from Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them and Quidditch Through the Ages, both published in 2001, went to Comic Relief.[282]

Rowling has contributed to support research and treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS), and those affected by COVID-19. Initially a contributor to the Scottish affiliate of the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Great Britain, she withdrew her support in 2009 after drawing attention to internal disputes in the organisation.[283] In 2010, she donated £10 million to found a MS research centre at the University of Edinburgh, named in honour of her mother Anne, who died of MS.[284][285] She donated six-figure sums from The Ickabog royalites to both Khalsa Aid and the British Asian Trust for coronavirus relief.[154] An inflatable representation of Lord Voldemort and other children's literary characters[286] accompanied Rowling reading from J. M. Barrie's Peter Pan as part of a tribute to Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children during the 2012 Summer Olympics opening ceremony in London.[287]

In May 2008, bookseller Waterstones asked Rowling and 12 other writers to compose a short piece on a single A5 postcard, which would then be sold at auction in aid of the charities Dyslexia Action and English PEN. Rowling's contribution was an 800-word Harry Potter prequel[288] that became part of the What's Your Story Postcard Collection.[289] The original manuscript was stolen in 2017.[290]

After her exposure as the true author of The Cuckoo's Calling led to a massive increase in sales, Rowling donated her royalties to the Army Benevolent Fund, saying she had always intended to but never expected the book to be a best-seller.[140][291]

Views

Politics

Rowling has centre-left political views.[292] In 2008, she donated £1 million to the Labour Party and publicly endorsed Labour Prime Minister Gordon Brown over Conservative challenger David Cameron, praising Labour's policies on child poverty.[293] That same year, in an interview with the Spanish-language newspaper El País, when asked about the 2008 United States presidential election, she said that the outcome would have a "profound effect on the rest of the world".[294] Regarding who she wanted to see elected, she stated that "it is a pity that Clinton and Obama have to be rivals because both are extraordinary".[294] In the same interview, she identified Robert F. Kennedy as her hero.[294]

In Rowling's "Single mother's manifesto", published in The Times in April 2010, she criticised then–Conservative Prime Minister Cameron's plan to encourage married couples to stay together by offering them a £150 annual tax credit.[295][non-primary source needed]

Rowling stated in 2012 that she is "pro-Union" and would vote 'No' on the 2014 Scottish independence referendum;[296] she donated £1 million to the Better Together anti-independence campaign.[297] She compared some Scottish Nationalists with the Death Eaters, characters from Harry Potter who are scornful of those without pure blood.[298] In June 2016, she campaigned for the United Kingdom to stay in the European Union in the run-up to the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum, stating, "I'm the mongrel product of this European continent and I'm an internationalist."[299] She expressed concern that "racists and bigots" were directing parts of the Leave campaign. In a blog post, she added: "How can a retreat into selfish and insecure individualism be the right response when Europe faces genuine threats, when the bonds that tie us are so powerful, when we have come so far together?"[300]

In 2015, Rowling joined 150 others in signing a letter published in The Guardian espousing cultural engagement with Israel.[301] Rowling expanded on her position, stating that although she opposed most of Benjamin Netanyahu's actions, depriving Israelis of shared culture would not dislodge Netanyahu,[302] and that "sharing of art and literature across borders constitutes an immense power for good".[303]

Religion

Rowling identifies as a Christian, stating that "I believe in God, not magic."[304] She began attending a Church of Scotland congregation around the time she was writing Harry Potter,[305] and her eldest daughter, Jessica, was baptised there.[214][305] She has said that she has struggled with doubt, that she believes in an afterlife,[306] and that her struggles about her faith play a part in her books.[294][307] In a 2012 radio interview, Rowling stated that she was a member of the Scottish Episcopal Church, a province of the Anglican Communion.[308]

Press

By 2011, Rowling had taken more than 50 actions against the press.[309] In a 2003 interview, she described herself as "too thin-skinned" with regard to the press.[310] Rowling has expressed dislike of the British tabloid Daily Mail.[311] In 2014, she successfully sued the Mail for libel over an article about her time as a single mother.[312]

In September 2011, Rowling was named as a "core participant" in the Leveson Inquiry into the culture, practices and ethics of the British press, as one of dozens of celebrities who may have been the victim of phone hacking.[313] In November 2012, Rowling wrote an op-ed for The Guardian in response to David Cameron's decision not to implement the full recommendations of the Leveson inquiry, stating that she felt "duped and angry".[314] In 2014, Rowling reaffirmed her support for "Hacked Off", a campaign supporting the self-regulation of the press, by co-signing a declaration to "[safeguard] the press from political interference while also giving vital protection to the vulnerable" with other British celebrities.[315]

Transgender people

In December 2019, Rowling tweeted her support for Maya Forstater, a British woman who initially lost her employment tribunal case (Maya Forstater v Centre for Global Development) but won on appeal against her former employer, the Center for Global Development, after her contract was not renewed due to her comments about transgender people.[316][317][318] She defended a British researcher :"Dress however you please," Rowling wrote on Twitter at the time. "Call yourself whatever you like. Sleep with any consenting adult who'll have you. Live your best life in peace and security. But force women out of their jobs for stating that sex is real?"[319]

On 6 June 2020, Rowling tweeted criticism of the phrase "people who menstruate",[320] and stated "If sex isn't real, the lived reality of women globally is erased. I know and love trans people, but erasing the concept of sex removes the ability of many to meaningfully discuss their lives."[321] Rowling's tweets were criticised by GLAAD, who called them "cruel" and "anti-trans".[322][323] Some members of the cast of the Harry Potter film series criticised Rowling's views or spoke out in support of trans rights, including Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson, Rupert Grint, Bonnie Wright, and Katie Leung, as did Fantastic Beasts lead actor Eddie Redmayne and the fansites MuggleNet and The Leaky Cauldron.[324][325][326] The actress Noma Dumezweni (who played Hermione Granger in Harry Potter and the Cursed Child) initially expressed support for Rowling but backtracked following criticism.[327]

On 10 June 2020, Rowling published a 3,600-word essay on her website in response to the criticism.[42][328] She again wrote that many women consider terms like "people who menstruate" to be demeaning. She said that she was a survivor of domestic abuse and sexual assault, and stated that "When you throw open the doors of bathrooms and changing rooms to any man who believes or feels he's a woman ... then you open the door to any and all men who wish to come inside", while stating that most trans people were vulnerable and deserved protection.[329] Reuters reported that, in the United States, women's rights groups said in 2016 that 200 municipalities which allowed trans people to use women's shelters reported no rise in any violence as a result; they also said that excluding transgender people from facilities consistent with their gender makes them vulnerable to assault.[330] Rowling's essay was criticised by, among others, the children's charity Mermaids (which supports transgender and gender non-conforming children and their parents), Stonewall, GLAAD and the feminist gender theorist Judith Butler.[331][332][333][334][335][336] Rowling has been referred to as a trans-exclusionary radical feminist (TERF) on multiple occasions, though she rejects the label.[337] Rowling has received support from actors Robbie Coltrane[338] and Eddie Izzard,[339] and some feminists[340] such as activist Ayaan Hirsi Ali[341] and the radical feminist Julie Bindel.[340] The essay was nominated by the BBC for their annual Russell Prize for best writing.[342][343]

In August 2020, Rowling returned her Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Ripple of Hope Award after Kerry Kennedy released a statement expressing her "profound disappointment" in Rowling's "attacks upon the transgender community", which Kennedy called "inconsistent with the fundamental beliefs and values of RFK Human Rights and ... a repudiation of my father's vision".[344][345][346] Rowling stated that she was "deeply saddened" by Kennedy's statement, but maintained that no award would encourage her to "forfeit the right to follow the dictates" of her conscience.[344]

Awards and honours

Rowling has won numerous accolades for the Harry Potter series, including general literature prizes, honours in children's literature and speculative fiction awards. Some scholars feel that its reception exposed a literary prejudice against children's books: for instance, Prisoner of Azkaban was nominated for the Whitbread Book of the Year, but the award body gave it the children's prize instead (worth half the cash amount).[347] The series has won multiple British Book Awards, beginning with the Children's Book of the Year for Philosopher's Stone[348] and Chamber of Secrets,[349] followed by a shift to the more general Book of the Year for Half-Blood Prince.[350] It received speculative fiction awards such as the Hugo Award for Best Novel for Goblet of Fire.[351]

Rowling's early career awards include the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for services to children's literature in 2000,[352] and three years later, the Spanish Prince of Asturias Award for Concord.[353] She won the British Book Awards' Author of the Year and Outstanding Achievement prizes over the span of the Harry Potter series.[354][355] Following the publication of Deathly Hallows, Time named Rowling a runner-up for its 2007 Person of the Year, citing the social, moral, and political inspiration she gave her fans.[356] Two years later, she was recognized as a Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur by French President Nicolas Sarkozy;[357] leading magazine editors then named her the "Most Influential Woman in Britain" the following October.[11] Later awards include the Freedom of the City of London in 2012,[358] and for her services to literature and philanthropy, the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH) in 2017.[359]

Academic bodies have bestowed multiple honours on Rowling. She has received honorary degrees from the University of Aberdeen, University of St Andrews,[360] Dartmouth University,[361] University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh Napier University,[360] University of Exeter (which she attended)[362] and Harvard University, where she spoke at the 2008 commencement ceremony.[363] The same year, Rowling also won the University College Dublin's James Joyce Award.[361] Her other honours include fellowship of the Royal Society of Literature (FRSL),[364] Royal Society of Edinburgh (HonFRSE),[365] and Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (FRCPE).[366]

Rowling's other works have also received recognition. The fifth volume of the Cormoran Strike series won the British Book Awards' Crime and Thriller category in 2021.[367] At the 2011 British Academy Film Awards, the Harry Potter film series was named an Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema; Rowling shared this honour with producer David Heyman and members of the cast and crew.[368]

Bibliography

| Target/ Type |

Series/ Description |

Title | Date | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young adult fiction |

Harry Potter series | 1. Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone | 1997-06-26 | [76][77] |

| 2. Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets | 1998-07-02 | [76][369] | ||

| 3. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban | 1999-07-08 | [76][370] | ||

| 4. Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire | 2000-07-08 | [76][371] | ||

| 5. Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix | 2003-06-21 | [76][372] | ||

| 6. Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince | 2005-07-16 | [76][373] | ||

| 7. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows | 2007-07-21 | [87][374] | ||

| Harry Potter- related books |

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (supplement to the Harry Potter series) | 2001-03-12 | [375] | |

| Quidditch Through the Ages (supplement to the Harry Potter series) | 2001-03-12 | [376] | ||

| Harry Potter prequel (short story published in What's Your Story Postcard Collection) | 2008-07-01 | [289][290] | ||

| The Tales of Beedle the Bard (supplement to the Harry Potter series) | 2008-12-04 | [377] | ||

| Harry Potter and the Cursed Child (story concept for play) | 2016-07-30 premier |

[378][379] | ||

| Short Stories from Hogwarts of Power, Politics and Pesky Poltergeists | 2016-09-06 | [380] | ||

| Short Stories from Hogwarts of Heroism, Hardship and Dangerous Hobbies | 2016-09-06 | [381] | ||

| Hogwarts: An Incomplete and Unreliable Guide | 2016-09-06 | [382] | ||

| Harry Potter- related original screenplays |

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them | 2016-11-18 | [383] | |

| Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald | 2018-11-16 premier |

[384] | ||

| Adult fiction |

The Casual Vacancy | 2012-09-27 | [385] | |

| Cormoran Strike series (as Robert Galbraith) |

1. The Cuckoo's Calling | 2013-04-18 | [386] | |

| 2. The Silkworm | 2014-06-19 | [387] | ||

| 3. Career of Evil | 2015-10-20 | [388] | ||

| 4. Lethal White | 2018-09-18 | [389] | ||

| 5. Troubled Blood | 2020-09-15 | [390] | ||

| Children fiction |

The Ickabog | 2020-11-10 | [391][392] | |

| The Christmas Pig | 2021-10-12 | [393] | ||

| Non-fiction | Books | Very Good Lives: The Fringe Benefits of Failure and Importance of Imagination, illustrated by Joel Holland, Sphere. ISBN 978-1408706787. | 2015-04-14 | [394] |

| A love letter to Europe : an outpouring of love and sadness from our writers, thinkers and artists, Coronet (contributor). ISBN 978-1529381108 | 2019-10-31 | [395] | ||

| Articles | "The First It Girl: J. K. Rowling reviews Decca: the Letters by Jessica Mitford". Sussman, Peter Y., editor. The Daily Telegraph. | 2006-11-26 | [27][396] | |

| "The Fringe Benefits of Failure, and the Importance of Imagination". Harvard Magazine. | 2008-06-05 | [397] | ||

| "Gordon Brown – The 2009 Time 100". Time magazine. | 2009-04-30 | [398] | ||

| "The Single Mother's Manifesto". The Times. | 2010-04-14 | [295] | ||

| "I feel duped and angry at David Cameron's reaction to Leveson". The Guardian. | 2012-11-30 | [314] | ||

| "Isn't it time we left orphanages to fairytales?" The Guardian. | 2014-12-17 | [399] | ||

| Book | Foreword/ Introduction |

McNeil, Gil and Brown, Sarah, editors. Magic. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0747557463 | 2002-06-03 | [400] |

| Brown, Gordon. "Ending Child Poverty" in Moving Britain Forward. Selected Speeches 1997–2006. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0747588382 | 2006-09-25 | [27][401] | ||

| Anelli, Melissa. Harry, A History. Pocket Books. ISBN 978-1416554950 | 2008-11-04 | [402] |

Filmography

| Year | Title | Credited as | Notes | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actress | Screenwriter | Producer | Executive producer | ||||

| 2003 | The Simpsons | Yes | Voice cameo in "The Regina Monologues" | [403] | |||

| 2010 | Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1 | Yes | Film based on Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows | [103] | |||

| 2011 | Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 | Yes | |||||

| 2015 | The Casual Vacancy | Yes | Television miniseries based on The Casual Vacancy | [404] | |||

| 2016 | Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them | Yes | Yes | Film inspired by the Harry Potter supplementary book Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them | [108] | ||

| 2017–present | Strike | Yes | Television series based on Cormoran Strike novels | [405] | |||

| 2018 | Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald | Yes | Yes | Film inspired by Harry Potter supplementary book Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them | [406] | ||

Notes

- ^ Some sources differ on Rowling's precise place of birth. As of January 2022[update], Rowling's personal website said she was born at "Yate General Hospital near Bristol".[21] In interviews, Rowling has sometimes said she was born in Chipping Sodbury, which is near Yate.[23] Philip Nel says she was born in Chipping Sodbury General Hospital in Gloucestershire.[24]

- ^ St Michael's Primary School headmaster, Alfred Dunn, has been suggested as the inspiration for the Harry Potter headmaster Albus Dumbledore;[33] biographer Smith writes that Rowling's father, and other figures in her education, provide more likely examples.[34]

- ^ In 2020, it was reported that a company listing Rowling's husband, Neil Murray, as director had purchased Church Cottage and renovations were underway.[36]

- ^ Rowling says Jessica was named after Jessica Mitford and a boy would have been named Harry; according to biographer Smith (2002), Arantes says Jessica was named after Jezebel from the Bible.[53]

- ^ The Great Snape Debate, a book-length collection of essays assessing the character Severus Snape, appeared in 2007. The book is divided into two sections, written by the same authors, in which Snape is alternately praised and critiqued.[191] Alison Lurie, among other critics, has noted how the names of Rowling's characters typically evoke their personalities.[192][193]

References

- ^ Brannon, Julie (2009). "Rowling, J. K.". In Hamilton, Geoff; Jones, Brian (eds.). Encyclopedia of American Popular Fiction. New York: Facts on File. pp. 301–304. ISBN 978-0-8160-7157-9. OCLC 230801883.

- ^ a b Eyre, Charlotte (1 February 2018). "Harry Potter book sales top 500 million worldwide". The Bookseller. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018.

- ^ "Record for best-selling book series". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ a b "JK Rowling unveils The Ickabog, her first non-Harry Potter children's book". BBC News. 26 May 2020. Archived from the original on 30 May 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ^ a b Couric, Katie (18 July 2005). J.K. Rowling, the author with the magic touch Archived 28 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine. MSN. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Weisman, Aly (12 March 2012). "J.K. Rowling Is No Longer A Billionaire, Booted Off Forbes List". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Farr, Emma-Victoria (3 October 2012). "J.K. Rowling: Casual Vacancy tops fiction charts". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ a b "JK Rowling net worth — Sunday Times Rich List 2021". The Sunday Times. 21 May 2021. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Gibbs, Nancy (19 December 2007). Person of the Year 2007: Runners-Up: J.K. Rowling Archived 21 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Time magazine. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ^ a b Pearse, Damien (11 October 2010). "Harry Potter creator J.K. Rowling named Most Influential Woman in the UK". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 25 October 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ a b c "Harry Potter and the mystery of J K's lost initial". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 49.

- ^ Weldon, Michele (8 November 2000). "A not-so-typical mum, J.K. Rowling can still relate". Chicago Tribune. p. 8.1. ProQuest 419156071.

- ^ Anelli 2008, p. 49.

- ^ a b "Christmas wedding for Rowling". BBC News. 30 December 2001. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "Judge rules against JK Rowling in privacy case". The Guardian. Press Association. 7 August 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Greig, Geordie (10 January 2006). "'There would be so much to tell her...'". The Daily Telegraph. p. 25. ProQuest 321301864.

- ^ "Witness statement of Joanne Kathleen Rowling" (PDF). The Leveson Inquiry. November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- ^ Rowling. "Rowling, Joanne Kathleen". Who's Who. Vol. 2015 (online Oxford University Press ed.). A & C Black.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Unknown parameter|othernames=ignored (help) (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required) - ^ a b c d e "About". J.K. Rowling. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Kirk 2003, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Nel 2001, p. 7.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 10.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 175.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Parker, Ian (24 September 2012). "Mugglemarch: J.K. Rowling writes a realist novel for adults". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 30 July 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 72.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "The JK Rowling story". The Scotsman. 16 June 2003. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ Sexton, Colleen A. (2008). J. K. Rowling. Brookfield, Conn: Twenty-First Century Books. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8225-7949-6. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 17.

- ^ "Happy birthday J.K. Rowling – here are 10 magical facts about the 'Harry Potter' author [Updated]". Los Angeles Times. 31 July 2010. Archived from the original on 5 August 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 28.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 19, 27–32, 51–52.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 24–27, 39, 88.

- ^ "Harry Potter: JK Rowling secretly buys childhood home". BBC News. 14 April 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 76.

- ^ a b J. K. Rowling (26 November 2006). "The first It Girl". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ a b Fraser, Lindsay (9 November 2002). "Harry and me". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. xii.

- ^ a b "J.K. Rowling Writes about Her Reasons for Speaking out on Sex and Gender Issues". J.K. Rowling. 10 June 2020. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Feldman, Roxanne (September 1999). "The truth about Harry". School Library Journal. 45 (9): 136–139. ProQuest 211722214.

- ^ Smith 2002, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 29.

- ^ Fraser 2001, p. 34.

- ^ Farr, Emma-Victoria (27 September 2012). "JK Rowling: 10 facts about the writer". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Norman-Culp, Sheila (19 December 1998). "Up the charts on a wizard's tale". Windsor Star. Associated Press. p. 80. Retrieved 5 January 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Biography". JK Rowling. Archived from the original on 26 December 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ Loer, Stephanie (18 October 1999). "All about Harry Potter from quidditch to the future of the Sorting Hat". The Boston Globe. p. C7. ProQuest 405306485.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 67.

- ^ Smith 2002, p. 132.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 57: "Soon, by many eyewitness accounts and even some versions of Jorge's own story, domestic violence became a painful reality in Jo's life.".

- ^ "J.K. Rowling Writes about Her Reasons for Speaking out on Sex and Gender Issues". J.K. Rowling. 10 June 2020. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

I've [...] never talked publicly about being a domestic abuse and sexual assault survivor. This isn't because I'm ashamed those things happened to me, but because they're traumatic to revisit and remember. I also feel protective of my daughter from my first marriage. I didn't want to claim sole ownership of a story that belongs to her, too. [...] I managed to escape my first violent marriage with some difficulty [...]

- ^ "JK Rowling: Sun newspaper criticised by abuse charities for article on ex-husband". BBC. 12 June 2020. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ a b c Rowling, JK (June 2008). "JK Rowling: The fringe benefits of failure". TED. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

Failure & imagination

- ^ "J.K. Rowling pondered suicide". Toronto Star. 24 March 2008. ISSN 0319-0781. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Chaundy, Bob (18 February 2003). "Harry Potter's magician". BBC News. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "JK Rowling awarded honorary degree". The Daily Telegraph. London. 8 July 2004. Archived from the original on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Anelli 2008, p. 44.

- ^ Dunn, Elisabeth (30 June 2007). "From the dole to Hollywood". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 23 April 2010. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Kirk 2003, pp. 55, 60.

- ^ a b c d Hahn, Daniel (2015). The Oxford Companion to Children's Literature (2d ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 264–266. ISBN 978-0-19-174437-2. OCLC 921452204.

- ^ Mamary, Anne J. M., ed. (22 December 2020). "Introduction". The Alchemical Harry Potter: Essays on Transfiguration in J. K. Rowling's Novels. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-1-4766-8134-4. OCLC 1155570319.

- ^ a b Zipes 2013, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Abravanel, Genevieve (2012). Americanizing Britain: The Rise of Modernism in the Age of the Entertainment Empire. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 161–163. ISBN 978-0-19-975445-8. OCLC 747530801.

- ^ Clark 2003, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Gupta 2009, p. 85.

- ^ Anelli 2008, pp. 41, 47.

- ^ Anelli 2008, p. 43.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 75.

- ^ Lawless, John (3 July 2005). "Revealed: The eight-year-old girl who saved Harry Potter". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ Blais, Jacqueline (9 July 2005). Harry Potter has been very good to JK Rowling. USA Today. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g "A Potter timeline for muggles". Toronto Star. 14 July 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ a b Errington 2017, p. 2.

- ^ McDougall, Liam (30 November 2003). "Arts Council: pay us back if you succeed". Sunday Herald. p. 8. ProQuest 331402052.

- ^ Anelli 2008, pp. 50, 58–59.

- ^ Kirk 2003, p. 79.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone". Kirkus Reviews. 1 September 1998. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ^ Anelli 2008, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Anelli 2008, p. 63.

- ^ "Potter's award hat-trick". BBC News. 1 December 1999. Archived from the original on 26 May 2004. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ a b "Harry Potter finale sales hit 11m". BBC News. 23 July 2007. Archived from the original on 28 November 2008. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ Pauli, Michelle (15 January 2003). "June date for Harry Potter 5". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "Potter 'is fastest-selling book ever'". BBC News. 22 June 2003. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Sawyer, Jenny (25 July 2007). "Missing from 'Harry Potter" – a real moral struggle". The Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ "Final Harry Potter is expected to set record". The Boston Globe. Associated Press. 29 June 2007. Archived from the original on 6 August 2009. 29 June 2007. Retrieved 29 June 2007.

- ^ Walker, Andrew (9 October 1998). "Harry Potter is off to Hollywood – making writer a millionairess". The Scotsman. p. 9. ProQuest 326708687.

- ^ Anelli 2008, p. 66.

- ^ Anelli 2008, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Anelli 2008, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (28 October 2021). "Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone review – 20 years on, it's a nostalgic spectacular". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Boucher, Jeff (13 March 2008). "Final 'Harry Potter' book will be split into two movies". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ^ "WB Sets Lots of New Release Dates!". Comingsoon.net. 24 February 2009. Archived from the original on 12 December 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ "Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema in 2011 – The Harry Potter Films". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. 2011. Archived from the original on 6 February 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (12 November 2010). "A Screenwriter's Hogwarts Decade". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ Sragow, Michael (15 November 2001). "The wizard behind 'Harry'". The Baltimore Sun. p. 1E. ProQuest 406491574.

- ^ Billington, Alex. Exclusive Video Interview: 'Harry Potter' Producer David Heyman Archived 14 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine. firstshowing.net. 9 December 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ^ a b Warner Bros. Pictures mentions J. K. Rowling as producer. Archived 27 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine Business Wire. 22 September 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ^ Treneman, Ann (30 June 2000). "Harry and me". The Times. pp. 43–46. ProQuest 318301486; Gale IF0501372629.

- ^ Fordy, Tom (3 January 2022). "JK Rowling's battle to make the Harry Potter films '100 per cent British'". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Coke backs Harry Potter literacy drive". BBC News. 9 October 2001. Archived from the original on 20 June 2006. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ Bettig, Ronald V.; Hall, Jeanne Lynn (2003). Big Media, Big Money: Cultural Texts and Political Economics. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 57. ISBN 0-7425-1129-4. OCLC 50003972.

- ^ a b "Warner Bros. Announces Expanded Creative Partnership with J.K. Rowling". Warner Bros. Pictures. Business Wire. 22 September 2010. Archived from the original on 15 September 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ "JK Rowling plans five Fantastic Beasts films". BBC. 27 November 2016. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016.

- ^ Crouch, Aaron (22 September 2021). ""Fantastic Beasts: The Secrets of Dumbledore' Sets New 2022 Release Date". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ "Scottish homes market view 2008: Perthshire". The Times UK. 28 September 2008. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

Their best-known owner, JK Rowling, "The Laird of Killiechassie", purchased her strip of premium Perthshire from Jackson for about £600,000 in 2001 – a bargain by today's standards.

- ^ "Hogwarts hideaway for Potter author". The Scotsman. 22 November 2001. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ "JK Rowling weds doctor lover in secret Boxing Day ceremony". The Scotsman. 30 December 2001. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ "Baby joy for JK Rowling". BBC News. London. 24 March 2003. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ J.K. Rowling's Official Site, "JKR gives Birth to Baby Girl". Retrieved 25 January 2005. Archived at Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c Hills, Megan C. (7 May 2020). "JK Rowling net worth 2020: How much the Harry Potter author earns and donates to charity". Evening Standard. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ Watson, Julie; Kellner, Tomas (26 February 2004). "J.K. Rowling and the Billion-Dollar Empire". Forbes. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ "Google Founders Join Forbes' Growing List of Billionaires". Los Angeles Times. 27 February 2004. p. C.3. ProQuest 421875391.

- ^ "Can't Buy Me Love". New York Times. 28 February 2004. p. A14. ProQuest 432672248.

- ^ "Financial wizardry". St. Louis Post – Dispatch. 29 February 2004. p. B.2. ProQuest 402371511.

- ^ "J.K. Rowling: Billionaire to millionaire". The New Zealand Herald. 12 March 2012. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ "The 25 Authors Who've Made The Most Money in The Last Decade". lithub.com. 13 March 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ "JK Rowling named world's highest-earning author by Forbes". BBC News. 4 August 2017. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "Worlds Highest-paid Authors 2019: J.K. Rowling Back on Top With $92 Million". Forbes. 20 December 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ "Review: 'The Casual Vacancy'". Publishers Weekly. 27 September 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "JK Rowling announces The Casual Vacancy as title of first book for adults". The Guardian. Press Association. 12 April 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ Battersby, Matilda (4 October 2012). "JK Rowling's 'The Casual Vacancy' tops book charts". The Independent. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Pugh 2020, p. 115.

- ^ Stone, Philip (9 October 2012). "Casual Vacancy keeps pole position". The Bookseller. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Frost, Vicky (28 January 2015). "Could the BBC/HBO adaptation of JK Rowling's The Casual Vacancy be an improvement on the book?". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ Brooks, Richard (14 July 2013). "Whodunnit? J. K. Rowling's Secret Life As A Wizard Crime Writer Revealed". The Sunday Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Hern, Alex (14 July 2013). "Sales of The Cuckoo's Calling" surge by 150". New Statesman. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ a b Frith, Maxine (16 July 2013). "Harry Plotter?". London Evening Standard. pp. 20–21.

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (14 July 2013). "This Detective Novel's Story Doesn't Add Up". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Watts, Robert (13 July 2013). "JK Rowling unmasked as author of acclaimed detective novel". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Pugh 2020, p. 116.

- ^ a b Meikle, James (18 July 2013). "JK Rowling directs anger at lawyers after secret identity revealed". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ^ Goldsmith, Belinda. "Real-life mystery of JK Rowling's 'secret' novel uncovered". trust.org. Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ Meikle, James (18 July 2013). "JK Rowling directs anger at lawyers after secret identity revealed". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ a b Schonfeld, Zach (31 July 2013). "J.K. Rowling Is Donating Her 'Cuckoo's Calling' Royalties to Charity". The Atlantic. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Chatterjee, Lopamudra (6 March 2014). "Robert Galbraith's novel 'The Silkworm' to be released in June". News 18. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Wilken, Selina (11 June 2015). "J.K. Rowling helps out Robert Galbraith, unveils 'Career of Evil' cover and publication date". Hypable. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "Lethal White: JK Rowling reveals Strike release date". BBC News. 10 July 2018. Archived from the original on 27 October 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ^ Rodger, James (19 February 2020). "JK Rowling announces fifth Cormoran Strike novel Troubled Blood under pseudonym Robert Galbraith". Birmingham Mail. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (26 October 2016). "HBO Picks Up 'Cormoran Strike' Drama Based on J.K. Rowling's Crime Novels". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017.

- ^ Brown, Jen. Stop your sobbing! More Potter to come . MSNBC. 24 July 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ^ Ulin, David L. "J.K. Rowling brings magic touch to U.S." Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 19 October 2007. 16 October 2007. Retrieved 30 October 2007.