Palestinian refugees: Difference between revisions

Enthusiast01 (talk | contribs) →Right of return: tidy up |

Enthusiast01 (talk | contribs) →Right of return: ref to voting on UN Res 194 |

||

| Line 71: | Line 71: | ||

{{main|Palestinian right of return}} |

{{main|Palestinian right of return}} |

||

Palestinian leaders claim a [[Palestinian right of return|right of return]] for Palestinian refugees. Their claim is based on Article 13 of the [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]] (UDHR), which declares that "Everyone has the right to leave any country including his own, and to return to his country." |

Palestinian leaders claim a [[Palestinian right of return|right of return]] for Palestinian refugees. Their claim is based on Article 13 of the [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]] (UDHR), which declares that "Everyone has the right to leave any country including his own, and to return to his country." Overlooking the fact that all [[Arab League]] members at the time - [[Egypt]], [[Iraq]], [[Lebanon]], [[Saudi Arabia]], [[Syria]], and [[Yemen]] - voted against the resolution [http://domino.un.org/UNISPAL.NSF/9a798adbf322aff38525617b006d88d7/2dac0ed54bcd6af68525629f00718b98!OpenDocument], they also cite [[United Nations General Assembly]] [[UN General Assembly Resolution 194|Resolution 194]], which "Resolves that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return [...]."<ref name="k">{{cite news|author=|year=1948|url=http://daccessdds.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/043/65/IMG/NR004365.pdf?OpenElement|title=[[United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194]]|format=PDF|publisher=United Nations|accessdate=2007-11-20|accessyear=2007}}</ref> |

||

The [[Palestinian National Authority]] supports this claim, although it has been prepared to negotiate its implementation at the various peace talks. Both Fatah and Hamas hold a strong position for a right of return; with Fatah being prepared to discuss the issue while Hamas is not.<ref>R. Brynen, 'Addressing the Palestinian Refugee Issue: A Brief Overview' (McGill University, background paper for the Refugee Coordination Forum, Berlin, April 2007), p.15, available at http://www.arts.mcgill.ca/mepp/new_prrn/research/papers/brynen-070514.pdf (11/03/08)</ref> |

The [[Palestinian National Authority]] supports this claim, although it has been prepared to negotiate its implementation at the various peace talks. Both Fatah and Hamas hold a strong position for a right of return; with Fatah being prepared to discuss the issue while Hamas is not.<ref>R. Brynen, 'Addressing the Palestinian Refugee Issue: A Brief Overview' (McGill University, background paper for the Refugee Coordination Forum, Berlin, April 2007), p.15, available at http://www.arts.mcgill.ca/mepp/new_prrn/research/papers/brynen-070514.pdf (11/03/08)</ref> |

||

Revision as of 21:55, 11 October 2008

| Total population: | 4.25 million[1] |

|---|---|

| Regions with significant populations: | Gaza Strip, Jordan, West Bank, Lebanon, Syria |

| Languages: | Arabic |

| Religions: | Sunni Islam, Greek Orthodoxy, Greek Catholicism, Other forms of Christianity |

Palestinian refugees are individuals, predominantly Arabs, who fled or were expelled during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War from their homes within that part of the British Mandate of Palestine that became the territory of the State of Israel. The term originated during the first Palestinian Exodus (Arabic: النكبة, Nakba, "catastrophe"), the beginning of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) defines a Palestinian refugee as a person "whose normal place of residence was Palestine between June 1946 and May 1948, who lost both their homes and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 Arab-Israeli conflict". They should not be confused with Jewish refugees from Arab states who were forced to leave their homes in 1948. UNRWA's definition of a refugee also covers the descendants of persons who became refugees in 1948[2] regardless of whether they reside in areas designated as refugee camps or in established, permanent communities.[3] Based on this definition the number of Palestinian refugees has grown from 711,000 in 1950[4] to over four million registered with the UN in 2002. This is a major exception to the normal definition of refugee. Descendants of Palestinian refugees under the authority of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) are the only group to be granted refugee status on that basis alone.[5]

Some displaced Palestinians resettled in other countries where their situation is often precarious. Many remained refugees and continue to reside in refugee camps.

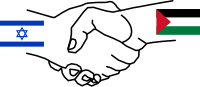

The issue of Palestinian refugees is often cited as a potential 'deal breaker' to the Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations.[2]

Reasons for the exodus

Palestinian Arabs fled from their homes during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War for several reasons, including the fear generated by the war, forcible expulsions by Jewish militias, destruction of Arab homes and settlements, and actual or claimed atrocities. Benny Morris puts the main causes for the Palestinian exodus as:-

"Above all let me reiterate, the refugee problem was caused by attacks by Jewish forces on Arab villages and towns and by the inhabitants' fear of such attacks, compounded by expulsions, atrocities, and rumour of atrocities - and by the crucial Israeli Cabinet decision in June 1948 to bar a refugee return."[6]

Immediately after the Arab-Israeli conflict, Israel started a process of nation building. General elections were held in January 1949. Chaim Weizmann was elected Israel's first president and Ben-Gurion as head of the Mapai party became prime minister, a position that he held in the Provisional Government.

The Israeli government adopted the position in June 1948, and reiterated in a letter to the United Nations on 2 August 1949, that a solution to the Palestinian refugee problem must be sought, not through the return of the refugees to Israel, but through the resettlement of the Palestinian Arab refugee population in other states.[7]

Scale

The number of Palestinians who fled or were expelled from their homes in the former Mandate territory of Palestine during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War is disputed. Estimates of how many refugees were displaced range from 367,000 to over 950,000. Most remained within the Palestinian territories of Gaza and the West Bank, within the Mandate territory, but a large number fled to neighboring countries. The final United Nations estimate of people displaced was 711,000,[4] but according to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), the number of registered refugees was 914,000 by 1950.[2] The UNRWA definition of who it regards as a refugee includes descendants of the Palestinian refugees born after the Palestinian exodus. The UN Conciliation Commission attributed this discrepancy to, among other things, "duplication of ration cards, addition of persons who have been displaced from area other than Israeli-held areas and of persons who, although not displaced, are destitute", and the UNRWA additionally attributed it to the fact that "all births are eagerly announced, the deaths wherever possible are passed over in silence," as well as the fact that "the birthrate is high in any case, a net addition of 30,000 names a year". By June 1951, the UNRWA had reduced the number of registered refugees to 876,000 after "many false and duplicate registrations [were] weeded out".[5]

Between 1948 and 1953 between 30,000 and 90,000 refugees, according to Benny Morris, made their way from their countries of exile to resettle in their former villages or in other parts of Israel, despite Israeli legal and military efforts to stop them (see Palestinian immigration (Israel)). At the Lausanne Conference of 1949, Israel offered to let in up to 75,000 more as part of a wider proposed deal with the surrounding Arab countries. The Arab countries rejected the offer, and Israel withdrew the proposal in 1950. Others emigrated to other countries, such as the United States and Canada. Most, however, remained in refugee camps in neighboring countries.

The number of Palestinian refugees by country as of 2005 were as follows:

- Jordan 1,827,877 refugees

- Gaza 986,034 refugees

- West Bank 699,817 refugees

- Syria 432,048 refugees

- Lebanon 404,170 refugees

- Saudi Arabia 240,000 refugees

- Egypt 70,245 refugees[1]

The Israeli government passed the Absentee Property Law, which allowed for the confiscation of the property of refugees. The government demolished many of the refugees' villages and settled Jewish refugees in urban Arab communities.[citation needed]

| Part of a series on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict |

| Israeli–Palestinian peace process |

|---|

|

UNRWA definition

Whereas most refugees are the concern of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), most Palestinian refugees - those in the West Bank, Gaza Strip, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan - come under the older body UNRWA. On 11 December 1948, UN Resolution 194 was passed. It called, among other things, for the return of refugees from Arab-Israeli hostilities then ongoing, although it did not specify only Arab refugees. Resolution 302 (IV) of 8 December 1949, set up UNRWA specifically to deal with the Palestinian refugee problem. Palestinian refugees outside of UNRWA's area of operations do fall under UNHCR's mandate, however.

The United Nations never formally defined the term Palestinian refugee. The definition used in practice evolved independently of the UNHCR definition, established by the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. The UNRWA definition of a refugee is as a person "whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948 and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict,"[8] This definition has generally only been applied to those who living in one of the countries where UNRWA provides relief. The UNRWA also registers as refugees descendants in the male line of Palestinian refugees, and persons in need of support who first became refugees as a result of the 1967 conflict. The UNRWA definition in practice is thus both more restrictive and more inclusive than the 1951 definition. For example, the definition excludes persons taking refuge in countries other than Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, but includes descendants of refugees as well as the refugees themselves. In many cases UNHCR provides support for the children of refugees too.

Persons receiving relief support from UNRWA are explicitly excluded from the 1951 Convention, depriving them of some of the benefits of that convention such as some legal protections. However, a 2002 decision of UNHCR made it clear that the 1951 Convention applies at least to Palestinian refugees who need support but fail to fit the UNRWA working definition.[9] UNRWA records show about 5% "False and duplicate registration"[9] Today, about 30% of those registering with the UNRWA as Palestinian refugees are living in areas designated as refugee camps.[10]

Critics of UNRWA say that the present definition give Palestinian refugees a favored status when compared with other refugee groups, which the UNHCR defines in terms of nationality as opposed to a relatively short number of years of residency.[11] Defenders of UNRWA respond that it is precisely the stateless status of the Palestinians under British mandate in 1948 that made it necessary to create a definition of refugee based on other criteria than nationality. Historians, such as Martha Gellhorn and Dr. Walter Pinner have also blamed UNRWA for distortion of statistics and even of sheer fraud. Pinner wrote in 1959 that the actual number of refugees then was only 367,000.[12]

Right of return

Palestinian leaders claim a right of return for Palestinian refugees. Their claim is based on Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which declares that "Everyone has the right to leave any country including his own, and to return to his country." Overlooking the fact that all Arab League members at the time - Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Yemen - voted against the resolution [3], they also cite United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194, which "Resolves that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return [...]."[13]

The Palestinian National Authority supports this claim, although it has been prepared to negotiate its implementation at the various peace talks. Both Fatah and Hamas hold a strong position for a right of return; with Fatah being prepared to discuss the issue while Hamas is not.[14]

The Israeli government, with minor variations over time, has generally opposed a Palestinian right of return and negotiations. There have been several reasons for this rejection, partly relating to the very origin of the Palestinian refugee problem. One of these is the view that Israel is not fully responsible for the 1948 refugees, and this is often linked to the argument that the refugees were instructed by Palestinian leaders to leave the country themselves. This account is squarely at odds with Arab assertions that the Palestinians were 'forcibly expelled' by Israel.[15]

Three other main factors explaining Israel’s opposition to the right of return principle relate to what has been called the ‘population transfer’ argument, and also to the nature of the demography of Israel. Firstly, it has been argued that when the state of Israel was created there was a tacit assumption of a ‘population transfer’ between the new Israeli state and the Arab countries, so that along with the exodus of Palestinian Arabs from Palestine there was also an influx of Jewish refugees from surrounding Arab states. But as Jordan had no Jewish population and Lebanon had a very small Jewish Population and Syria had a very small Jewish population and the bulk of the Egyptian Jewish population did not emigrate until long after the Palestinian Arabs had been made refugees the argument is disingenuous. This has been frequently cited by Israeli officials as negating the Palestinian right of return. Secondly, it is seen that such a right of return would also undermine one of the most significant characteristics of Israel, which was at the core of its establishment – namely that it is a Jewish state. Thirdly, racial tensions between the two groups would most likely lead to increased conflict, and that increased conflict would not suit the purposes of either ethnic group.[16]

Ruth Lapidoth of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs notes that Resolution 194, as a General Assembly resolution, is non-binding, and further outlines a recommendation that refugees be allowed to return, and not a right of return. She adds that the 1951-1967 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees does not explicitly mention descendants in its definition of refugees, and that "humanitarian law conventions (such as the 1949 Geneva Conventions for the Protection of Victims of War) do not recognize a right of return." Lapidoth does maintain, however, that refugees have a right to compensation for their property.[3]

Equality with Jewish refugees

On April 3rd, 2008 US passed a legislation urging the president that any reference to Palestinian refugees must “also include a similarly explicit reference to the resolution of the issue of Jewish refugees from Arab countries.” [4].

Joseph Crowley (D-NY) one of the sponsors of the bipartisan decision - which passed without objections - expressed sympathy for the Jewish refugees and claimed that few know about them.[citation needed]

Treatment in Arab countries

| Part of a series on |

| Palestinians |

|---|

|

| Demographics |

| Politics |

|

| Religion / religious sites |

| Culture |

| List of Palestinians |

After the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, Arab governments expressed concern for Palestinian refugees and criticised Israel for standing in the way of helping the refugees. Critics argue the Arab governments could have easily provided the refugees with new homes, just as Israel resettled Jewish immigrants and refugees from foreign countries. Arab governments did not grant refugees citizenship and did not provide funds to improve the conditions in refugee camps.[17] Some parties criticise the lack of government assistance to relieve the refugee crisis as a way of using the Palestinian Arabs as political pawns, exploiting them as tools against Israel and promoting anti-Israel sentiment.[18][19]

In 1957, the Refugee Conference at Homs, Syria, passed a resolution stating that "Any discussion aimed at a solution of the Palestine problem which will not be based on ensuring the refugees' right to annihilate Israel will be regarded as a desecration of the Arab people and an act of treason (Beirut al Massa, July 15, 1957)."[20]

The Arab League issued instructions barring the Arab states from granting citizenship to Palestinian Arab refugees (or their descendants) "to avoid dissolution of their identity and protect their right to return to their homeland".[21]

Syrian Prime Minister, Khalid al-Azm, wrote in his 1973 memoirs:

Since 1948 it is we who demanded the return of the refugees [...] while it is we who made them leave. [...] We brought disaster upon [...] Arab refugees, by inviting them and bringing pressure to bear upon them to leave. [...] We have rendered them dispossessed. [...] We have accustomed them to begging. [...] We have participated in lowering their moral and social level. [...] Then we exploited them in executing crimes of murder, arson, and throwing bombs upon [...] men, women and children-all this in the service of political purposes.

Jordan is the only Arab country which uniformly gave citizenship rights to Palestinian refugees present on its soil. Other countries, especially Lebanon, gave citizenship to a fraction of the refugees.[citation needed] However, there remain a huge number of refugees living in camps in Jordan, and in fact it has the largest such population with over one million Palestinian refugees.[22]

Jordan

After the 1967 Six-Day War, during which Israel captured the West Bank from Jordan, Palestinian Arabs living there continued to have the right to apply for Jordanian passports and live in Jordan. Palestinian refugees actually living in Jordan were considered full Jordanian citizens as well. In July 1988, King Hussein of Jordan announced the severing of all legal and administrative ties with the West Bank. Any Palestinian living on Jordanian soil would remain and be considered Jordanian. However, any person living in the West Bank would have no right to Jordanian citizenship.

Jordan still issues passports to Palestinians in the West Bank, but they are for travel purposes only and do not constitute an attestation of citizenship. Palestinians in the West Bank who had regular Jordanian passports were issued these temporary ones upon expiration of their old ones, and entry into Jordan by Palestinians is time-limited and considered for tourism purposes only. Any Jordanian citizen who is found carrying a Palestinian passport (issued by the Palestinian Authority and Israel) has his/her Jordanian citizenship revoked by Jordanian border agents.

More recently, Jordan has restricted entry of Palestinians from the West Bank into its territory, fearing that many Palestinians would try to take up temporary residence in Jordan during the Al-Aqsa Intifada. This has caused many hardships for Palestinians, especially since 2001 when Israel discontinued permission for Palestinians to travel through its Ben Gurion International Airport, and traveling to Jordan to fly out of Amman became the only outlet for West Bank Palestinians to travel.

Information from the Jordanian censuses which distinguishes between Palestinians and pre-1948 Arab-Israeli War Jordanians is not publicly available, and it is widely believed that Palestinians in Jordan (domiciled in Jordan and considered citizens) constitute the majority of the kingdom's population. However, in a 2002 television interview on a US network, King Abdullah II of Jordan assured that "Jordanians of Palestinian Origin" are only 40-45% of the Jordanian population, and that an independent survey would be conducted to settle the matter.[23]

Saudi Arabia

As of December 2004, an estimated 240,000 Palestinians live in Saudi Arabia.[24]

Lebanon

Lebanon barred Palestinians from 73 job categories including professions such as medicine, law and engineering. They are not allowed to own property. Unlike other foreigners in Lebanon, they are denied access to the Lebanese healthcare system. The Lebanese government refused to grant them work permits or permission to own land. The number of restrictions has been mounting since 1990.[25] In June 2005, however, the government of Lebanon removed some work restrictions from a few Lebanese-born Palestinians, enabling them to apply for work permits and work in the private sector.[26] In a 2007 study, Amnesty International denounced the "appalling social and economic condition" of Palestinians in Lebanon.[27]

Lebanon gave citizenship to about 50,000 Palestinian refugees during the 1950s and 1960s. In the mid-1990s, about 60,000 refugees who were Shiite Muslim majority were granted citizenship. This caused a protest from Maronite authorities, leading to citizenship being given to all the Palestinian Christian refugees who were not already citizens.[28] There are still about 350,000 non-citizen Palestinian refugees in Lebanon.

In the 1940s, the Lebanese government registered most Palestinians as Arabs in order to get Arab funds from the Gulf states as well as UN grants to boost its corrupted economy and eliminate inflation. Noteworthy, according to official Palestinian estimates, a large number within the Palestinian refugees from the Acre region of British Palestine were adherers of the Shiite Islam of the Twelvers school, a minority being of Sunnite Islam of the Hanafite school, and most of non-Arab origins, including Turks, Azeris, Albanians, and Bosnians.[citation needed]

Following major armed conflict in one camp in 2007, the Lebanese Government sought greater input into the rebuilding of the camp, and in the camp's ongoing management. The government wanted the ability to intervene in the future, and to exercise police powers there. [29]

Kuwait and Egypt

After the Gulf War of 1990-1991, Kuwait and other Gulf Arab monarchies expelled more than 400,000 Palestinian refugees[30]) in response to the PLO support of Iraq during the invasion of Kuwait.

During Egypt's occupation of the Gaza Strip, Egypt denied the Gaza Strip's residents citizenship rights and did not allow them to move to Egypt or anywhere outside of the Strip. From 1949-1967, The Gaza Strip was used by Egypt to launch 9,000 attacks on Israel from terrorist cells set up in refugee camp.[citation needed] Egypt today abides by the instructions of the Arab League concerning Palestinians of not granting them citizenship.

Iraq

Palestinians in Iraq have come under increasing pressure to leave since the beginning of the Iraq War in 2003. Hundreds of Palestinians were evicted from their homes by Iraqi landlords following the fall of Saddam Hussein. 19,000 Palestinians, over half the community's number in Baghdad, have fled since that time, and remaining Palestinians regularly face "threats, killings, intimidation, and kidnappings". Several hundred refugees are trapped on the border with Syria, which refuses to grant them entry.[31][32]

See also

- Estimates of the Palestinian Refugee flight of 1948

- Palestinian Exodus (Nakba)

- Arab-Israeli conflict

- United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East

- Palestinian refugee camps

- List of villages depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war

- Jewish exodus from Arab lands

- Jewish refugees

- Palestinian diaspora

Further reading

- Gelber, Yoav (2006). Palestine 1948. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 1-84519-075-0.

- Morris, Benny (2003). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521009677

- Seliktar, Ofira (2002). Divided We Stand: American Jews, Israel, and the Peace Process. Praeger/Greenwood. ISBN 0-275-97408-1

References

- ^ a b "Total registered refugees per country and area" (PDF). United Nations. 2005. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Who is a Palestinian refugee?" (HTML). UNRWA. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Ruth Lapidoth (2002). "Legal aspects of the Palestinian refugee question" (HTML). Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "General Progress Report and Supplementary Report of the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine, Covering the Period from [[11 December]] [[1949]] to [[23 October]] [[1950]]" (HTML). United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine. 1950. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Publications/Statistics" (HTML). UNRWA. 2006. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "e" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Eugene L. Rogan and Avi Shlaim 2007 p. 38

- ^ UN Doc. IS/33 2 August 1948Text of a statement made by Moshe Sharett on 1 August 1948

- ^ "UNRWA's Frequently Asked Questions under "Who is a Palestine refugee?" begins "For operational purposes, UNRWA has defined Palestine refugee as any person whose "normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948 and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict." Palestine refugees eligible for UNRWA assistance, are mainly persons who fulfill the above definition and descendants of fathers fulfilling the definition."" (HTML). United Nations. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Note on the Applicability of Article 1D of the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees to Palestinian refugees" (HTML). United Nations. 2002. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "g" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Arlene Kushner (2004). "United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees in the Near East" (PDF). Israel Resource News. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); line feed character in|title=at position 39 (help) - ^ "Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees" (PDF). UNHCR. 1951 and 1967. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Pinner, Dr. Walter (1959 and 1967). How many refugees? and The Legend of the Arab Refugees. McGibbon & Kee. pp. ?.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ "[[United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194]]" (PDF). United Nations. 1948. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

{{cite news}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ R. Brynen, 'Addressing the Palestinian Refugee Issue: A Brief Overview' (McGill University, background paper for the Refugee Coordination Forum, Berlin, April 2007), p.15, available at http://www.arts.mcgill.ca/mepp/new_prrn/research/papers/brynen-070514.pdf (11/03/08)

- ^ I. Pappe (ed.), The Israel-Palestine Question: A Reader (Routledge, London, 2007), pp.149-50.

- ^ http://www.arts.mcgill.ca/mepp/new_prrn/background/background_resolving.htm (11/03/08)

- ^ Bamberger, David (1994). A Young Person's History of Israel. Behrman House. p. 182. ISBN 0-87441-393-1.

- ^ History in a Nutshell

- ^ European Coalition for Israel|Documentation

- ^ The Palestinian Refugees

- ^ A Million Expatriates to Benefit From New Citizenship Law by P.K. Abdul Ghafour, Arab News. October 21 , 2004. Accessed July 20, 2006

- ^ Palestinian refugees and the right of return, cnn.com, accessed 5/30/07.

- ^ Transcript of interview with HM King Abdullah at the Charlie Rose Show. May 7, 2002

- ^ "The Palestinian and Israeli People: Palestinian Refugees," Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) Committee on Disarmament, Peace and Security

- ^ Poverty trap for Palestinian refugees By Alaa Shahine. 29 March 2004 (aljazeera)

- ^ Lebanon permits Palestinians to work June 29, 2005 (Arabicnews)

- ^ Exiled and suffering: Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, 17 October 2007 web.amnesty.org

- ^ Simon Haddad, The Origins of Popular Opposition to Palestinian Resettlement in Lebanon, International Migration Review, Volume 38 Number 2 (Summer 2004):470-492. Also Peteet [1].

- ^ Palestinians' bitter-sweet homecoming in Lebanon By William Wheeler, Christian Science Monitor via Yahoo news, 3/5/08.

- ^ Mahmoud Abbas has apologized for the Palestinians' support of Saddam Hussein during the 1990 invasion of Kuwait 12 December, 2004 (BBC

- ^ Palestinians Under Pressure To Leave Iraq The Washington Post, January 25, 2007.

- ^ More Palestinians fleeing Baghdad arrive at Syrian border Reuters Alertnet, January 26, 2007.

External links

- The Palestinian Refugee Issue: Rhetoric vs. Reality by Sidney Zabludoff

- Ben-Dror Yemini: AND THE WORLD LIES, a global comparison between palesinians and other groups of refugees.

- Efraim Karsh: Benny Morris' Reign of Error, Revisited, Middle East Quarterly, Morris still blames Israel for the Palestinian refugee crisis.

- Palestinian Refugee ResearchNet

- Palestinian Rights Portal

- Palestinian Rights Portal

- United Nations: A Question of Palestine

- UN Resolution 194

- UN Resolution 302

- Israeli viewpoint

- The Palestinian Refugees

- CNN

- Washington Post

- Monde diplomatique: Statistics of the refugees

- PLO position

- Palestinian Arab viewpoint

- Jewish refugees

- American ViewpointA

- American ViewpointB

- Newspaper Analysis of Refugee Situation

- Badil Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights

- The Feasibility of the Right to Return

- FAQ from the Al-Awda Foundation

- Why Palestinians Still Live in Refugee Camps

- Palestinian Right of Return or Strategic Weapon?: A Historical, Legal and Moral Political Analysis

- "The Palestinian Diaspora: A History of Dispossession". From Global Exchange.

- "Sands of Sorrow" 1950 video about the refugees (about 29 minutes long).

- "Aix Group" Economic Solution to the Palestinian Refugees within a Two-State Final Status Agreement.

- "LPDC"