Scientology: Difference between revisions

→Hubbard's early life: added citations and referenced information from Urban. |

→Beliefs and practices: without specific page numbers being cited, this information will hold back the article quality. Everything has to be cited very precisely to pages in Reliable Sources. |

||

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

According to Scientology, its beliefs and practices are based on rigorous research, and its doctrines are accorded a significance equivalent to scientific laws.<ref name="GA170-171">{{harvnb|Cowan|Bromley|2006 |pp=170–171}}</ref>Blind belief is held to be of lesser significance than the practical application of Scientologist methods.<ref name="GA170-171" /> Adherents are encouraged to validate the practices through their personal experience.<ref name="GA170-171" /> Hubbard put it this way: "For a Scientologist, the final test of any knowledge he has gained is, 'did the data and the use of it in life actually improve conditions or didn't it?{{Single double}}<ref name="GA170-171" /> |

According to Scientology, its beliefs and practices are based on rigorous research, and its doctrines are accorded a significance equivalent to scientific laws.<ref name="GA170-171">{{harvnb|Cowan|Bromley|2006 |pp=170–171}}</ref>Blind belief is held to be of lesser significance than the practical application of Scientologist methods.<ref name="GA170-171" /> Adherents are encouraged to validate the practices through their personal experience.<ref name="GA170-171" /> Hubbard put it this way: "For a Scientologist, the final test of any knowledge he has gained is, 'did the data and the use of it in life actually improve conditions or didn't it?{{Single double}}<ref name="GA170-171" /> |

||

Hubbard described Scientology as an "applied religious philosophy" because, according to him, it consists of a metaphysical doctrine, a theory of psychology, and teachings in morality.<ref>{{cite conference |last=Dericquebourg |first=Regis |title=Acta Comparanda |language=en, fr |url=http://www.observatoire-religion.com/2016/12/scientology-in-a-scholarly-perspective/ |book-title=Affinities between Scientology and Theosophy |conference=International Conference – Scientology in a scholarly perspective 24–25th January 2014 |publisher=University of Antwerp, Faculty for Comparative Study of Religions and Humanism |place=Antwerp, Belgium |year=2014 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170216050903/http://www.observatoire-religion.com/2016/12/scientology-in-a-scholarly-perspective/ |archive-date=February 16, 2017}}</ref> The core of Scientology teaching lies in the belief that "each human has a reactive mind that responds to life's traumas, clouding the analytic mind and keeping us from experiencing reality." Scientologists undergo auditing to discover sources of this trauma, believing that re-experiencing it neutralizes it and reinforces the ascendancy of the analytic mind, with the final goal believed to be achieving a spiritual state that Scientology calls "clear".<ref name="cnn.com"/> |

|||

The scholar of religion [[Dorthe Refslund Christensen]] described Scientology as being "a religion of practice" rather than "a religion of belief."{{sfn|Christensen|2009b|p=412}} As promoted by the Church, Scientology involves progressing through a series of levels, at each of which the practitioner is deemed to gain release from certain problems as well as enhanced abilities.{{sfn|Bromley|2009|p=94}} The degree system was probably adopted from earlier European institutions, including [[Freemasonry]] and the [[Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn]].{{sfn|Bainbridge|2009|p=43}} Although many of Hubbard's writings and other Scientology documents are protected by the Church and not accessible to either non-members or members below a certain rank, some of them have been leaked by various ex-members.{{sfnm|1a1=Rothstein|1y=2009|1p=367|2a1=Thomas|2y=2021|2p=14, 81}} |

The scholar of religion [[Dorthe Refslund Christensen]] described Scientology as being "a religion of practice" rather than "a religion of belief."{{sfn|Christensen|2009b|p=412}} As promoted by the Church, Scientology involves progressing through a series of levels, at each of which the practitioner is deemed to gain release from certain problems as well as enhanced abilities.{{sfn|Bromley|2009|p=94}} The degree system was probably adopted from earlier European institutions, including [[Freemasonry]] and the [[Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn]].{{sfn|Bainbridge|2009|p=43}} Although many of Hubbard's writings and other Scientology documents are protected by the Church and not accessible to either non-members or members below a certain rank, some of them have been leaked by various ex-members.{{sfnm|1a1=Rothstein|1y=2009|1p=367|2a1=Thomas|2y=2021|2p=14, 81}} |

||

Revision as of 16:59, 21 January 2023

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (January 2023) |

Scientology is a set of beliefs and practices invented by American author L. Ron Hubbard, and an associated movement. It has been variously defined as a cult, a business, or a new religious movement.[11] The primary exponent of Scientology is the Church of Scientology, a centralized and hierarchical organization based in Florida, although many practitioners exist independently of the Church, in what is called the Free Zone. Estimates put the number of Scientologists at under 40,000 worldwide.

Hubbard initially developed a set of ideas that he called Dianetics, which he represented as a form of therapy. This he promoted through various publications, as well as through the Hubbard Dianetic Research Foundation that he established in 1950. The foundation went bankrupt, and Hubbard lost the rights to his book Dianetics in 1952. He then recharacterized the subject as a religion and renamed it Scientology, retaining the terminology, doctrines, and the practice of "auditing".[7][12][13] By 1954 he had regained the rights to Dianetics and retained both subjects under the umbrella of the Church of Scientology.[20]

Scientology teaches that a human is an immortal, spiritual being (Thetan) that resides in a physical body and has had innumerable past lives. Some Scientology texts are only revealed after followers have spent more than $200,000 in the organization, and it charges tens of thousands of dollars for access to these texts in what it calls "Operating Thetan" levels. The organization has gone to considerable lengths to try to keep these secret, but they are freely available on the internet.[21] These texts say that lives preceding a Thetan's arrival on Earth were lived in extraterrestrial cultures. The Scientology doctrine states that any Scientologist undergoing "auditing" will eventually come across and recount a common series of events.[22] They include reference to an extraterrestrial life-form called Xenu. The secret Scientology texts say this was a ruler of a confederation of planets 70 million years ago who brought billions of alien beings to Earth and then killed them with thermonuclear weapons. Despite being kept secret from most followers, this forms the central mythological framework of Scientology's ostensible soteriology: attainment of a status referred to by Scientologists as "clear". These aspects have become the subject of popular ridicule.[23]

From soon after their formation, Hubbard's groups have generated considerable opposition and controversy, in several instances because of their illegal activities.[24] In January 1951, the New Jersey Board of Medical Examiners brought proceedings against the Dianetic Research Foundation on the charge of teaching medicine without a license.[25] During the 1970s, Hubbard's followers engaged in a program of criminal infiltration of the U.S. government, resulting in several executives of the organization being convicted and imprisoned for multiple offenses by a U.S. Federal Court.[26][27][28] Hubbard himself was convicted in absentia of fraud by a French court in 1978 and sentenced to four years in prison.[29] In 1992, a court in Canada convicted the Scientology organization in Toronto of spying on law enforcement and government agencies, and criminal breach of trust, later upheld by the Ontario Court of Appeal.[30][31] The Church of Scientology was convicted of fraud by a French court in 2009, a judgment upheld by the supreme Court of Cassation in 2013.[32]

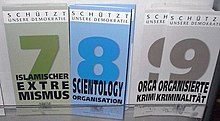

The Church of Scientology has been described by government inquiries, international parliamentary bodies, scholars, law lords, and numerous superior court judgments as both a dangerous cult and a manipulative profit-making business.[39] Following extensive litigation in numerous countries,[40][41] the organization has managed to attain a legal recognition as a religious institution in some jurisdictions, including Australia,[42][43] Italy,[41] and the United States.[44] Germany classifies Scientology groups as an "anti-constitutional sect",[45][46] while the French government classifies the group as a dangerous cult.[47][48]

Definition and classification

Arguments as to whether Scientology should be regarded as a religion have raged for years.[49] Many Scientologists consider it to be their religion.[50] Its founder, L. Ron Hubbard, presented it as such,[51] but the early history of the Scientology organization, and Hubbard's policy directives, letters, and instructions to subordinates, indicate that his motivation for doing so was as a legally pragmatic move.[6] In many countries the Church of Scientology has engaged in legal challenges to secure recognition as a tax-exempt religious organization,[52] and it is now legally recognized as such in many countries, including the United States, where it was founded.[53]

Many scholars of religion have referred to Scientology as a religion,[54] as has the Oxford English Dictionary.[55] The sociologist Bryan R. Wilson compared Scientology with 20 criteria that he associated with religion and concluded that the movement could be characterised as such.[56] Allan W. Black analysed Scientology through the seven "dimensions of religion" set forward by the scholar Ninian Smart and also decided that Scientology met those criteria for being a religion.[56] The sociologist David V. Barrett noted that there was a "strong body of evidence to suggest that it makes sense to regard Scientology as a religion",[57] while scholar of religion James R. Lewis commented that "it is obvious that Scientology is a religion."[58] More specifically, many scholars have described it as a new religious movement.[59] Various scholars have also considered it within the category of Western esotericism.[60]

Other commentators "seriously question" the categorisation of Scientology as a religion.[53] This categorisation as a religion is strongly opposed by the anti-cult movement,[61] with Scientology's critics often labelling it a "cult".[62] The Church has not received recognition as a religious organization in the majority of countries it operates in;[63] its claims to a religious identity have been particularly rejected in continental Europe, where anti-Scientology activists have had a greater impact on public discourse than in Anglophone countries.[64] These critics maintain that the Church is a commercial business that falsely claims to be religious,[65] or alternatively a form of therapy masquerading as religion.[66] The scholar of religion Andreas Grünschloß commented that those rejecting the categorisation of Scientology as a religion acted under the "misunderstanding" that to call it a religion means that "one has approved of its basic goodness."[67] He stressed that labelling Scientology a religion does not mean that it is "automatically promoted as harmless, nice, good, and humane."[68]

Scientology has experienced multiple schisms during its history.[69] While the Church of Scientology was the original promoter of the movement, various independent groups have split off to form Freezone Scientology. Referring to the "different types of Scientology," the scholar of religion Aled Thomas suggested it was appropriate to talk about "Scientologies."[70]

Etymology

The word Scientology, as coined by Hubbard, is a derivation from the Latin word scientia ("knowledge", "skill"), which comes from the verb scīre ("to know"), with the suffix -ology, from the Greek λόγος lógos ("word" or "account [of]").[71][72] The name "Scientology" deliberately makes use of the word "science", [73] seeking to benefit from the "prestige and perceived legitimacy" of natural science in the public imagination.[74] In doing so Scientology has been compared to religious groups like Christian Science and the Science of Mind which employed similar tactics.[75]

The term scientology had been used in published works at least twice before Hubbard. In The New Word (1901) poet and lawyer Allen Upward first used scientology to mean blind, unthinking acceptance of scientific doctrine (compare scientism).[76] In 1934, philosopher Anastasius Nordenholz published Scientology: Science of the Constitution and Usefulness of Knowledge, which used the term to mean the science of science.[77] It is unknown whether Hubbard was aware of either prior usage of the word.[78][79]

History

Hubbard's early life

Hubbard was born in 1911 in Tilden, Nebraska, the son of a U.S. naval officer.[80] His family were Methodists.[81] Six months later they moved to Oklahoma, and then to Montana, living on a ranch near Helena.[53] In 1923, Hubbard moved to Washington DC.[82] In 1927, he made a summer trip to Hawaii, China, Japan, the Philippines, and Guam, following this with a longer visit to East Asia in 1928.[82] In 1929 he returned to the U.S. to complete high school.[82] In 1930, he enrolled at George Washington University, where he began writing and publishing stories.[83][84] He left university after two years and in 1933 married his wife.[82]

Becoming a professional writer for pulp magazines,[85] Hubbard's first novel, Buckskin Brigades, appeared in 1937.[86] In 1935, he was elected president of the New York chapter of the American Fiction Guild.[86] From 1938 through till the 1950s, he was part of a group of writers associated with the pulp magazine Astounding Science-Fiction.[87] Historian of religion Hugh Urban related that Hubbard became one of the "key figures" in the "golden age" of pulp fiction.[88] In a later document called Excalibur, he recalled a near death experience while under anaesthetic during a dental operation in 1938.[89][90][91]

In 1940, Hubbard was commissioned as a lieutenant (junior grade) in the U.S. Navy. After the Pearl Harbor attack brought the U.S. into the Second World War, he was called to active duty, sent to the Philippines and then Australia.[92] After the war, he married for a second time and returned to writing.[93] He became involved with rocket scientist Jack Parsons and the latter's Agape Lodge, a Pasadena group practicing Thelema, the religion founded by occultist Aleister Crowley. Hubbard later broke from the group and eloped with Parsons' girlfriend Betty.[94] The Church of Scientology later claimed that Hubbard's involvement with the Agape Lodge was at the behest of the U.S. intelligence services,[95] although no evidence has appeared to substantiate this.[96] In 1952, Hubbard would call Crowley a "very good friend," despite having never met him;[97] the historian of religion Hugh Urban observed a "significant amount of Crowley's influence in the early Scientology beliefs and practices of the 1950s".[98]

During the late 1940s, Hubbard began developing Dianetics, a therapy system that he initially promoted through articles;[99] several appeared in Astounding Science Fiction, whose editor, John W. Campbell, was sympathetic to it.[100] In 1950, Hubbard's book, Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health, was published, becoming a bestseller.[101] He then founded the Hubbard Dianetic Research Foundation in Elizabeth, New Jersey, began teaching auditors, and lectured on the topic around the country.[102] The new Dianetics movement grew swiftly,[99] partly because it was more accessible than psychotherapy and promised more immediate progress.[103] In 1951, he introduced E-Meters into the auditing process.[104] Hubbard approached both the American Psychiatric Association and the American Medical Association, but neither took Dianetics seriously,[105] with much of the medical establishment regarding his ideas as pseudomedicine and pseudoscience.[51]

Dianetics

In May 1950, Hubbard's Dianetics: The Evolution of a Science was published by pulp magazine Astounding Science Fiction.[106][107] In the same year, he published the book-length Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health, considered the seminal event of the century by Scientologists.[citation needed] Scientologists sometimes use a dating system based on the book's publication; for example, "A.D. 25" does not stand for Anno Domini, but "After Dianetics".[108]

Dianetics describes a "counseling" technique known as "auditing" in which an auditor assists a subject in conscious recall of traumatic events in the individual's past. It was originally intended to be a new psychotherapy.[109][110] Hubbard variously defined Dianetics as a spiritual healing technology and an organized science of thought.[111] The stated intent is to free individuals of the influence of past traumas by systematic exposure and removal of the engrams (painful memories) these events have left behind, a process called clearing.[111] Rutgers scholar Beryl Satter says that "there was little that was original in Hubbard's approach", with much of the theory having origins in popular conceptions of psychology.[112] Satter observes that in "keeping with the typical 1950s distrust of emotion, Hubbard promised that Dianetic treatment would release and erase psychosomatic ills and painful emotions, thereby leaving individuals with increased powers of rationality."[112][113]

According to Gallagher and Ashcraft, in contrast to psychotherapy, Hubbard stated that Dianetics "was more accessible to the average person, promised practitioners more immediate progress, and placed them in control of the therapy process." Hubbard's thought was parallel with the trend of humanist psychology at that time, which also came about in the 1950s.[112] Passas and Castillo write that the appeal of Dianetics was based on its consistency with prevailing values.[114] Shortly after the introduction of Dianetics, Hubbard introduced the concept of the "Thetan" (or soul) which he claimed to have discovered. Dianetics was organized and centralized to consolidate power under Hubbard, and groups that were previously recruited into Dianetics were no longer permitted to organize autonomously.[115]

Two of Hubbard's key supporters at the time were John W. Campbell Jr., the editor of Astounding Science Fiction, and Campbell's brother-in-law, physician Joseph A. Winter.[116] Dr. Winter, hoping to have Dianetics accepted in the medical community, submitted papers outlining the principles and methodology of Dianetic therapy to the Journal of the American Medical Association and the American Journal of Psychiatry in 1949, but these were rejected.[117][118]

Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health spent six months on the New York Times bestseller list.[a][119] Publishers Weekly gave a posthumous plaque to Hubbard to commemorate Dianetics' appearance on its list of bestsellers for one hundred weeks.[108] Studies that address the topic of the origins of the work and its significance to Scientology as a whole include Peter Rowley's New Gods in America, Omar V. Garrison's The Hidden Story of Scientology, and Albert I. Berger's Towards a Science of the Nuclear Mind: Science-fiction Origins of Dianetics. More complex studies include Roy Wallis's The Road to Total Freedom.[108]

Dianetics appealed to a broad range of people who used instructions from the book and applied the method to each other, becoming practitioners themselves.[113] Dianetics soon faced criticism. Morris Fishbein, the editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association and well known at the time as a debunker of quack medicine, dismissed Hubbard's book.[120] An article in Newsweek stated that "the Dianetics concept is unscientific and unworthy of discussion or review".[121] Hubbard asserted that Dianetics is "an organized science of thought built on definite axioms: statements of natural laws on the order of those of the physical sciences".[122]

Hubbard became the leader of a growing Dianetics movement. He started giving talks about Dianetics and established the Hubbard Dianetic Research Foundation in Elizabeth, New Jersey, where he trained his first Dianetics "counselors" or auditors.[113]

Some practitioners of Dianetics reported experiences that they believed had occurred in past lives, or previous incarnations.[113] Hubbard took the reports of past life events seriously and introduced the concept of the Thetan, an immortal being analogous to the soul.[113] This was an important factor in the transition from secular Dianetics to the presenting of Scientology as an ostensible religion. Sociologists Roy Wallis and Steve Bruce suggest that Dianetics, which set each person as his or her own authority, was about to fail due to its inherent individualism, and that Hubbard started Scientology, framed as a religion, to establish himself as the overarching authority.[123][115]

Also in 1951, Hubbard incorporated the electropsychometer (E-meter for short), a kind of electrodermal activity meter, as an auditing aid. Based on a design by Volney Mathison, the device is held by Scientologists to be a useful tool in detecting changes in a person's state of mind. The global spread of Scientology in the latter half of the 1950s culminated with the opening of Church of Scientology buildings in Johannesburg and Paris, while world headquarters transferred to England in Saint Hill, a rural estate. Hubbard lived there for the next seven years.[124]

Dianetics is different from Scientology in that Scientology's advocates like to frame it as a religion. The purpose of Dianetics is the improvement of the individual, the individual or "self" being only one of eight "dynamics".[125] According to Hugh B. Urban, Hubbard's early science of Dianetics would be best comprehended as a "bricolage that brought together his various explorations in psychology, hypnosis, and science fiction". If Dianetics is understood as a bricolage, then Scientology is "an even more ambitious sort of religious bricolage adapted to the new religious marketplace of 1950s America", continues Urban. According to Roy Wallis, "Scientology emerged as a religious commodity eminently suited to the contemporary market of postwar America." L. Ron Hubbard Jr. said in an interview that the spiritual bricolage of Scientology, as written by Hugh B. Urban, "seemed to be uniquely suited to the individualism and quick-fix mentality of 1950s America: just by doing a few assignments, one can become a god".[7]

Harlan Ellison has told a story of seeing Hubbard at a gathering of the Hydra Club in 1953 or 1954. Hubbard was complaining of not being able to make a living on what he was being paid as a science fiction writer. Ellison says that Lester del Rey told Hubbard that what he needed to do to get rich was start a religion.[126]

In 1950, founding member Joseph Winter cut ties with Hubbard and set up a private Dianetics practice in New York.[117] In 1965, a longtime member of the Scientology organization and "Doctor of Scientology" Jack Horner (born 1927), dissatisfied with the organization's "ethics" program, developed Dianology.[127]

Establishing the Church of Scientology: 1951-1965

In January 1951, the New Jersey Board of Medical Examiners began proceedings against the Hubbard Dianetic Research Foundation for teaching medicine without a license, which eventually led to that foundation's bankruptcy.[129][130][131] In December 1952, the Hubbard Dianetic Foundation filed for bankruptcy, and Hubbard lost control of the Dianetics trademark and copyrights to financier Don Purcell.[132] Author Russell Miller argues that Scientology "was a development of undeniable expedience, since it ensured that he would be able to stay in business even if the courts eventually awarded control of Dianetics and its valuable copyrights to ... Purcell".[133][134]

L. Ron Hubbard originally intended for Scientology to be considered a science, as stated in his writings. In May 1952, Scientology was organized to put this intended science into practice, and in the same year, Hubbard published a new set of teachings as Scientology, a religious philosophy.[135] Marco Frenschkowski quotes Hubbard in a letter written in 1953, to show that he never denied that his original approach was not a religious one: "Probably the greatest discovery of Scientology and its most forceful contribution to mankind has been the isolation, description and handling of the human spirit, accomplished in July 1951, in Phoenix, Arizona. I established, along scientific rather than religious or humanitarian lines that the thing which is the person, the personality, is separable from the body and the mind at will and without causing bodily death or derangement. (Hubbard 1983: 55)."[136]

Following the prosecution of Hubbard's foundation for teaching medicine without a license, in April 1953 Hubbard wrote a letter proposing that Scientology should be transformed into a religion.[137] As membership declined and finances grew tighter, Hubbard had reversed the hostility to religion he voiced in Dianetics.[138] His letter discussed the legal and financial benefits of religious status.[138] Hubbard outlined plans for setting up a chain of "Spiritual Guidance Centers" charging customers $500 for twenty-four hours of auditing ("That is real money ... Charge enough and we'd be swamped."). Hubbard wrote:[139]

I await your reaction on the religion angle. In my opinion, we couldn't get worse public opinion than we have had or have less customers with what we've got to sell. A religious charter would be necessary in Pennsylvania or NJ to make it stick. But I sure could make it stick.

In December 1953, Hubbard incorporated three organizations – a "Church of American Science", a "Church of Scientology" and a "Church of Spiritual Engineering" – in Camden, New Jersey.[140] On February 18, 1954, with Hubbard's blessing, some of his followers set up the first local Church of Scientology, the Church of Scientology of California, adopting the "aims, purposes, principles and creed of the Church of American Science, as founded by L. Ron Hubbard".[140] In 1955, Hubbard established the Founding Church of Scientology in Washington, D.C.[113] The group declared that the Founding Church, as written in the certificate of incorporation for the Founding Church of Scientology in the District of Columbia, was to "act as a parent church for the religious faith known as 'Scientology' and to act as a church for the religious worship of the faith".[141]

During this period the organization expanded to Australia, New Zealand, France, the United Kingdom and elsewhere. In 1959, Hubbard purchased Saint Hill Manor in East Grinstead, Sussex, United Kingdom, which became the worldwide headquarters of the Church of Scientology and his personal residence. During Hubbard's years at Saint Hill, he traveled, providing lectures and training in Australia, South Africa in the United States, and developing materials that would eventually become Scientology's "core systematic theology and praxis.[142]

The Scientology organization experienced further challenges. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began an investigation concerning the claims the Church of Scientology made in connection with its E-meters. On January 4, 1963, FDA agents raided offices of the organization, seizing hundreds of E-meters as illegal medical devices and tons of literature that they accused of making false medical claims.[143] The original suit by the FDA to condemn the literature and E-meters did not succeed,[144] but the court ordered the organization to label every meter with a disclaimer that it is purely religious artifact,[145] to post a $20,000 bond of compliance, and to pay the FDA's legal expenses.[146]

In the course of developing Scientology, Hubbard presented rapidly changing teachings that some have seen as often self-contradictory.[147][148] According to Lindholm, for the inner cadre of Scientologists in that period, involvement depended not so much on belief in a particular doctrine but on unquestioning faith in Hubbard.[148]

With the Church often under heavy criticism, it adopted strong measures of attack in dealing with its critics.[149] In 1966, the Church established a Guardian's Office (GO), an intelligence unit devoted to undermining those hostile towards Scientology.[150] The GO launched an extensive program of countering negative publicity, gathering intelligence, and infiltrating hostile organizations.[151] In "Operation Snow White", the GO infiltrated the IRS and several other government departments and stole, photocopied, and then returned tens of thousands of documents pertaining to the Church, politicians, and celebrities.[152]

Hubbard's later life: 1966-1986

In 1966, Hubbard resigned as executive director of the Church.[153][113][154] From that point on, he focused on developing the advanced levels of training.[155] In 1967, Hubbard established a new elite group, the Sea Organization or "SeaOrg", the membership of which was drawn from the most committed members of the Church.[156] With its members living communally and holding senior positions in the Church,[157] the SeaOrg was initially based on three ocean-going ships, the Diana, the Athena, and the Apollo.[155][113] Reflecting Hubbard's fascination for the navy, members had naval titles and uniforms.[158] In 1975, the SeaOrg moved its operations from the ships to the new Flag Land Base in Clearwater, Florida.[159]

In 1972, facing criminal charges in France, Hubbard returned to the United States and began living in an apartment in Queens, New York.[160] In July 1977, police raids on Church premises in Washington DC and Los Angeles revealed the extent of the GO's infiltration into government departments and other groups.[161] 11 officials and agents of the Church were indicted; in December 1979 they were sentenced to between 4 and 5 years each and individually fined $10,000.[162] Among those found guilty was Hubbard's then-wife, Mary Sue Hubbard.[152] Public revelation of the GO's activities brought widespread condemnation of the Church.[162] The Church responded by closing down the GO and expelling those convicted of illegal activities.[162] A new Office of Special Affairs replaced the GO.[163] A Watchdog Committee was set up in May 1979, and in September it declared that it now controlled all senior management in the Church.[52]

At the start of the 1980s, Hubbard withdrew from public life,[164][165][166] with only a small number of senior Scientologists ever seeing him again.[52] 1980 and 1981 saw significant revamping at the highest levels of the Church hierarchy,[162] with many senior members being demoted or leaving the Church.[52] By 1981, the 21-year old David Miscavige, who had been one of Hubbard's closest aides in the SeaOrg, rose to prominence.[52] That year, the All Clear Unit (ACU) was established to take on Hubbard's responsibilities.[52] In 1981, the Church of Scientology International was formally established,[167] as was the profit-making Author Services Incorporated (ASI), which controlled the publishing of Hubbard's work.[168] In 1982, this was followed by the creation of the Religious Technology Center, which controlled all trademarks and service marks.[169][170] The Church had continued to grow; in 1980 it had centers in 52 countries, and by 1992 that was up to 74.[171]

Some senior members who found themselves side-lined regarded Miscavige's rise to dominance as a coup,[168] believing that Hubbard no longer had control over the Church.[172] Expressing opposition to the changes was senior member Bill Robertson, former captain of the Sea Org's flagship, Apollo.[158] At an October 1983 meeting, Robertson claimed that the organization had been infiltrated by government agents and was being corrupted.[173] In 1984 he established a rival Scientology group, Ron's Org,[174] and coined the term "Free Org" which came to encompass all Scientologists outside the Church.[174] Robertson's departure was the first major schism within Scientology.[173]

During his seclusion, Hubbard continued writing. His The Way to Happiness was a response to a perceived decline in public morality.[171] He also returned to writing fiction, including the sci-fi epic Battlefield Earth, and then the 10-volume Mission Earth.[171] In 1980, Church member Gerry Armstrong was given access to Hubbard's private archive so as to conduct research for an official Hubbard biography. Armstrong contacted the Messengers to raise discrepancies between the evidence he discovered and the Church's claims regarding Hubbard's life; he duly left the Church and took Church papers with him, which they regained after taking him to court.[175] Hubbard died at his ranch in Creston, California on January 24, 1986.[176][177]

After Hubbard: 1986-

Miscavige succeeded Hubbard as head of the Church.[158] In 1991, Time magazine published a frontpage story attacking the Church. The latter responded by filing a lawsuit and launching a major public relations campaign.[178] In 1993, the Internal Revenue Service dropped all litigation against the Church and recognized it as a religious organization,[179] with the UK's home office also recognizing it as a religious organization in 1996.[180] The Church then focused its opposition towards the Cult Awareness Network (CAN), a major anti-cult group. The Church was part of a coalition of groups what successfully sued CAN, which then collapsed as a result of bankruptcy in 1996.[181]

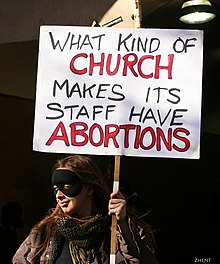

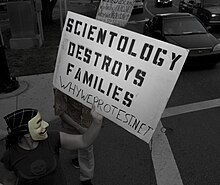

In 2008, the online activist collective Anonymous launched Project Chanology with the stated aim of destroying the Church; this entailed denial of service attacks against Church websites and demonstrations outside its premises.[182] In 2009, the St Petersburg Times began a new series of exposes surrounding alleged abuse of Church members, especially at their re-education camp at Gilman Hot Springs in California.[183] As well as prompting episodes of BBC's Panorama and CNN's AC360 investigating the allegations,[184] these articles launched a new series of negative press articles and books presenting themselves as exposes of the Church.[185] In 2012, Lewis commented on a recent decline in Church membership,[186] with those leaving for the Freezone including large numbers of high-level, long-term Scientologists.[187] These defectors have included Mark Rathbun and Mike Rinder, who have championed the cause of Independent Scientologists wishing to practice Scientology outside of the Church.[188][189]

Beliefs and practices

Hubbard lies at the core of Scientology.[190] His writings remain the source of Scientology's doctrines and practices,[191] with the sociologist of religion David G. Bromley describing the religion as Hubbard's "personal synthesis of philosophy, physics, and psychology."[192] Hubbard claimed that he developed his ideas through research and experimentation, rather than through revelation from a supernatural source.[193] He published hundreds of articles and books over the course of his life,[194] writings that Scientologists regard as scripture.[195] The Church encourages people to read his work chronologically, in the order in which it was written.[196] It claims that Hubbard's work is perfect and no elaboration or alteration is permitted.[197]

According to Scientology, its beliefs and practices are based on rigorous research, and its doctrines are accorded a significance equivalent to scientific laws.[198]Blind belief is held to be of lesser significance than the practical application of Scientologist methods.[198] Adherents are encouraged to validate the practices through their personal experience.[198] Hubbard put it this way: "For a Scientologist, the final test of any knowledge he has gained is, 'did the data and the use of it in life actually improve conditions or didn't it?'"[198]

Hubbard described Scientology as an "applied religious philosophy" because, according to him, it consists of a metaphysical doctrine, a theory of psychology, and teachings in morality.[199] The core of Scientology teaching lies in the belief that "each human has a reactive mind that responds to life's traumas, clouding the analytic mind and keeping us from experiencing reality." Scientologists undergo auditing to discover sources of this trauma, believing that re-experiencing it neutralizes it and reinforces the ascendancy of the analytic mind, with the final goal believed to be achieving a spiritual state that Scientology calls "clear".[200]

The scholar of religion Dorthe Refslund Christensen described Scientology as being "a religion of practice" rather than "a religion of belief."[201] As promoted by the Church, Scientology involves progressing through a series of levels, at each of which the practitioner is deemed to gain release from certain problems as well as enhanced abilities.[202] The degree system was probably adopted from earlier European institutions, including Freemasonry and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.[203] Although many of Hubbard's writings and other Scientology documents are protected by the Church and not accessible to either non-members or members below a certain rank, some of them have been leaked by various ex-members.[204]

Theology and cosmology

Scientology refers to the existence of a Supreme Being, but practitioners are not expected to worship it.[205] No intercessions are made to seek this Being's assistance in daily life.[206]

Many Scientologists avoid using the words "belief" or "faith" to describe how Hubbard's teachings impacts their lives. They perceive that Scientology is based on verifiable technologies, speaking to Hubbard's original scientific objectives for Dianetics, based on the quantifiability of auditing on the E-meter. Scientologists call Dianetics and Scientology as technologies because of their claim of their scientific precision and workability.[207]

Hubbard referred to the physical universe as the MEST universe, meaning "Matter, Energy, Space and Time".[208] In Scientology's teaching, this MEST universe is separate from the theta universe, which consists of life, spirituality, and thought.[209] Scientology teaches that the MEST universe is fabricated through the agreement of all thetans (souls or spirits) that it exists,[209] and is therefore an illusion that is only given reality through the actions of thetans themselves.[210]

Body and Thetan

Hubbard taught that there were three "Parts of Man," the spirit, mind, and body.[211] The first of these is a person's "true" inner self, a "theta being" or "thetan."[212] While the thetan is akin to the idea of the soul or spirit found in other traditions,[213] Hubbard avoided terms like "soul" or "spirit" because of their cultural baggage.[214] Hubbard stated that "the thetan is the person. You are YOU in a body."[209] The purpose of Scientology is to free the thetan from the confines of the physical MEST universe,[209] thus returning it to its original state.[215]

According to Scientology, a person's thetan has existed for trillions of years,[210] long before the physical body.[215] In their original form, the thetans were simply energy, separate from the physical universe.[210] Each thetan had its own "Home Universe," and it was through the collision of these that the physical MEST universe emerged.[210] Once MEST was created, Scientology teaches, the thetans began experimenting with human form, ultimately losing knowledge of their origins and becoming trapped in physical bodies.[210] Scientology also maintains that a series of "universal incidents" have undermined the thetans' ability to recall their origins.[210]

Hubbard taught that Thetans brought the material universe into being largely for their own pleasure.[216] The universe has no independent reality but derives its apparent reality from the fact that Thetans agree it exists.[217] Thetans fell from grace when they began to identify with their creation rather than their original state of spiritual purity.[216] Eventually they lost their memory of their true nature, along with the associated spiritual and creative powers. As a result, Thetans came to think of themselves as nothing but embodied beings.[217]

This idea of liberating the spiritual self from the physical universe has drawn comparisons with Buddhism,[209] although Hubbard’s understanding of Buddhism during the 1950s was limited.[218] Scientological literature has presented its teachings as the continuation and fulfilment of The Buddha’s ideas.[219] In one publication, Hubbard toyed with the idea that he was Maitreya, the future enlightened being prophesied in some forms of Mahayana Buddhism.[220] The concept of the thetan has also been observed as being very similar to those promulgated in various mid-20th century UFO religions.[193]

Reincarnation

Scientology teaches the existence of reincarnation;[221] Hubbard taught that each individual has experienced "past lives", although generally avoided using the term "reincarnation" itself.[222] The movement claims that once a body dies, the thetan enters another body which is preparing to be born.[210] It rejects the idea that the thetan will be born into a non-human animal on Earth.[223] In Have You Lived Before This Life?, Hubbard recounted accounts of past lives stretching back 55 billion years, often on other planets.[97]

Reactive mind, traumatic memories, and auditing

Prior to establishing Scientology, Hubbard formed a system termed "Dianetics" [224] and it is from this that Scientology grew.[225]

Scientology presents two major divisions of the mind.[226] The reactive mind is thought to record all pain and emotional trauma, while the analytical mind is a rational mechanism that serves consciousness.[217][227] Hubbard claimed that the "reactive" mind stores traumatic experiences in pictorial forms which he termed "engrams."[228] Dianetics holds that even if the traumatic experience is forgotten, the engram remains embedded in the reactive mind.[224] Hubbard maintained that humans develop engrams from as far back as during incubation in the womb,[224] as well as from their "past lives".[229] The existence of engrams has never been verified through scientific investigation.[230] According to Scientology, engrams are painful and debilitating; as they accumulate, people move further away from their true identity.[216] To avoid this fate is Scientology's basic goal.[216]

L. Ron Hubbard described the analytical mind in terms of a computer: "the analytical mind is not just a good computer, it is a perfect computer." According to him it makes the best decisions based on available data. Errors are made based on erroneous data and is not the error of the analytical mind.[207]

Auditing

According to Dianetics, engrams can be deleted through a process termed "auditing".[224] Auditing remains the central activity within Scientology,[231] and has been described by scholars of religion as Scientology's "core ritual",[232] "primary ritual activity,"[233] and "most sacred process."[234] This usually involves a question and answer session between an auditor and their client.[235][236] An electronic device called the Hubbard Electrometer or electro-psychometer, or more commonly the E-meter, is also typically involved.[237] The client holds two metal canisters, which are connected via a cable to the main box part of the device. This emits a small electrical flow through the client and then back into the box, where it is measured on a needle.[238] It thus detects fluctuations in electrical resistance within the client's body.[237][236]

The auditor operates two dials on the main part of the device; the larger is the "tone arm" and is used to adjust the voltage, while the smaller "sensitivity knob" influences the amplitude of the needle's movement.[197] The auditor then interprets the needle's movements as it responds when the client is asked and answers questions.[197] The movement of the needle is not visible to the client and the auditor writes down their observations rather than relaying them to the client.[197] Hubbard claimed that the E-Meter "measures emotional reaction by tiny electrical impulses generated by thought".[239] Scientologists believe that the auditor locates the points of resistance and converts their form into energy, which can then be discharged.[202] The auditor is believed to be able to detect items that the client may not wish to admit or which is concealed below the latter's consciousness.[240] Throughout, they are trained to observe the client's emotional state in accordance with an "emotional tone scale."[241] Auditing can be an emotional experience for the client, with some crying during it.[242]

Scientology asserts that people have hidden abilities which have not yet been fully realized.[243] It teaches that increased spiritual awareness and physical benefits are accomplished through sessions referred to as "auditing", for which the organization charges hundreds of dollars per hour. There is no evidence of any of these notional benefits being realized.[244] Scientology doctrine claims that through auditing, people can solve their problems and free themselves of engrams.[245] It also claims that this restores them to their "natural condition" as Thetans and enables them to be "at cause" in their daily lives, responding rationally and creatively to life events, rather than reacting to them under the direction of stored engrams.[246] Accordingly, those who study Scientology materials and receive auditing sessions advance from a status of Preclear to Clear and Operating Thetan.[247] Scientology's utopian aim is to "clear the planet", that is, clear all people in the world of their engrams.[248]

Scientology teaches that the E-meter helps to locate spiritual difficulties.[236] Once an area of concern has been identified, the auditor asks the individual specific questions about it to help him or her eliminate the difficulty, and uses the E-meter to confirm that the "charge" has been dissipated.[236] As the individual progresses up the "Bridge to Total Freedom", the focus of auditing moves from simple engrams to engrams of increasing complexity and other difficulties.[236] At the more advanced OT levels, Scientologists act as their own auditors ("solo auditors").[236]

Going through a full course of auditing with the Church is expensive,[249] although the prices are not often advertised publicly.[250] In a 1964 letter, Hubbard stated that a 25 hour block of auditing should cost the equivalent of "three months' pay for the average middle class working individual."[250] In 2007, the fee for a 12 and a half hour block of auditing at the Tampa Org was $4000.[251] The Church is often criticised for the prices it charges for auditing.[251] Hubbard stated that charging for auditing was necessary because the practice required an exchange, and should the auditor not receive something for their services it could harm both parties.[251]

Going Clear

The process of removing all engrams both from past and present lives transforms the individual from a state of being "Pre-Clear" to a state of "Clear."[252] Once a person is Clear, Scientology teaches that they are capable of new levels of spiritual awareness.[253] In the 1960s, the Church stated that a "Clear is wholly himself with incredible awareness and power."[222] It claims that a Clear will have better health, improved hearing and eyesight, and greatly increased intelligence;[254] Hubbard claimed that Clears do not suffer from colds or allergies.[255] Hubbard stated that anyone who becomes Clear will have "complete recall of everything which has ever happened to him or anything he has ever studied".[256] Individuals who have reached Clear have claimed a range of superhuman abilities, including seeing through walls, remote viewing, and telepathic communication.[97]

Emotional Tone Scale and survival

Scientology uses an emotional classification system called the tone scale.[257] The tone scale is a tool used in auditing; Scientologists maintain that knowing a person's place on the scale makes it easier to predict his or her actions and assists in bettering his or her condition.[258]

Scientology emphasizes the importance of survival, which it subdivides into eight classifications that are referred to as "dynamics".[259] An individual's desire to survive is considered to be the first dynamic, while the second dynamic relates to procreation and family.[259] The remaining dynamics encompass wider fields of action, involving groups, mankind, all life, the physical universe, the spirit, and infinity, often associated with the Supreme Being.[259] The optimum solution to any problem is believed to be the one that brings the greatest benefit to the greatest number of dynamics.[259]

Toxins and purification

Scientology teaches that auditing can also be hindered if the client is under the influence of drugs.[260] New Scientologists are thus advised to undertake the Purification Rundown for two to three weeks to detoxify the body prior to embarking on an auditing course.[261] Also known as the Purification Program or Purif, the Purification Rundown focuses on removing the influence of both medical and recreational drugs from the body through a routine of exercise, saunas, and healthy eating.[262] The Church has Purification Centres where these activities can take place in most of its Orgs,[260] while Freezoners have sometimes employed public saunas for the purpose.[263] Other Freezone Scientologists have argued that the impact of drugs can be countered through ordinary auditing, with no need for the Purification Rundown.[264]

Introspection Rundown

The Introspection Rundown is a controversial Church of Scientology auditing process that is intended to handle a psychotic episode or complete mental breakdown. Introspection is defined for the purpose of this rundown as a condition where the person is "looking into one's own mind, feelings, reactions, etc."[265] The Introspection Rundown came under public scrutiny after the death of Lisa McPherson in 1995.[266]

The Operating Thetan Levels

The degrees above the level of Clear are called "Operating Thetan" or OT.[267] Hubbard described there as being 15 OT levels, although had only completed eight of these during his lifetime;[268] OT levels nine to 15 have not been reached by any Scientologist.[269] Scholar of religion Aled Thomas suggested that the status of a persons level creates an internal class system within the Church.[270]

To gain the OT levels of training, a Church member must go to one of the Advanced Organisations or Orgs, which are based in Los Angeles, Clearwater, East Grinstead, Copenhagen, Sydney, and Johannesburg.[271] OT levels six and seven are only available at Clearwater.[272] The highest level, OT VIII, is disclosed only at sea on the Scientology ship Freewinds, operated by the Flag Ship Service Org.[273] The Church claims that the material taught in the OT levels can only be comprehended once its previous material has been mastered and is therefore kept confidential until a person reaches the requisite level,[274] with higher-level Church members refusing to talk about the contents of these OT levels.[275] Those progressing through the OT levels are taught additional, more advanced auditing techniques;[214] one of the techniques taught is a method of auditing oneself,[276] which is the necessary procedure for reaching OT level seven.[272]

Space opera and the Wall of Fire

Scientology refers to "space opera," a term denoting events in the distant past in which "spaceships, spacemen, [and] intergalactic travel" all feature.[277] This represents a strong science-fiction theme within Scientology's theology.[278] Rothstein referred to the "Xenu myth" as "the basic (sometimes implicit) mythology of the movement".[279] It is a story that concerns humanity's origins on Earth.[279]

Hubbard wrote about a great catastrophe that took place 75 million years ago,[280] and which was referred to as "Incident 2," one of the "Universal Incidents" that hinder the thetan's ability to remember its origins.[210] According to this story, 75 million years ago there was a Galactic Federation of 76 planets ruled over by a leader called Xenu. The Federation was overpopulated and to deal with this problem Xenu transported large numbers of people to the planet Teegeeack (Earth). He then detonated hydrogen bombs inside volcanoes to wipe out these people.[281] The bombed thetans were then "packaged," by which Hubbard meant that they were clustered together. Implants were inserted into them, designed to kill anyone who recalled the event of their destruction.[282] After the Teegeeack massacre, several of the officers in his service rebelled against him, ultimately capturing and imprisoning him.[283]

Hubbard claimed to have discovered the Xenu myth in December 1967, having taken the "plunge" deep into his "time track."[284] He commented that he was "probably the only one ever to do so in 75,000,000 years."[282] Scientology teaches that attempting to recover this information from the "time track" typically results in an individual's death due to Xenu's implants, but that because of Hubbard's "technology" that is no longer necessary.[285]

According to these documents, the bodies of those Xenu placed on Teegeeack were destroyed but their inner thetans survived and continue to carry the trauma of this event.[210] Scentology maintains that some of these traumatised thetans which lack bodies of their own become "body thetans," clustering around living people and negatively impacting them.[286] Many of the advanced auditing techniques taught to Scientologists focus on dealing with these body thetans, awakening them from the amnesia they experience and allowing them to detach from the bodies they cluster around. Once free they are capable of either being born into bodies of their choosing or remaining detached from any physical form.[287]

As the Church argues that learning the Xenu myth can be harmful for those unprepared for it,[288] the documents discussing Xenu were restricted for those Church members who had reached the OT III level, known as the "Wall of Fire."[289] These OT III teachings about Xenu were later leaked by ex-members,[290] and are now widely available online.[291] The teachings were submitted as evidence in court cases involving Scientology, thus becoming a matter of public record.[292][293] The Church claims that the leaked documents have been distorted,[294] and that the OT level texts are only religiously meaningful in the context of the OT courses in which they are provided, thus being incomprehensible to outsiders.[295] Church members who have reached the OT III level routinely deny these teachings exist.[296] Hubbard however talked about Xenu on several occasions,[297] the Xenu story bears similarities with some of the science-fiction stories Hubbard published,[298] and Rothstein noted that "substantial themes from the Xenu story are detectable" in Hubbard's book Scientology – A History of Man.[299]

Critics of Scientology regularly employ reference to Xenu to mock the movement,[300] believing that the story will be regarded as absurd by outsiders and thus prove detrimental to Scientology.[301] Critics have also highlighted factual discrepancies regarding the myth; geologists demonstrate that the Mauna Loa volcano, which appears in the myth, is far younger than 75 million years old.[297] Scientologists nevertheless regard it as a factual account of past events.[302]

Scientology ceremonies

Ceremonies overseen by the Church fall into two main categories; Sunday services and rarer ceremonies marking particular events in a person's life.[303] In Scientology, ceremonies for events such as weddings, child naming, and funerals are observed.[216] Friday services are held to commemorate the completion of a person's services during the prior week.[216] Ordained Scientology ministers may perform such rites.[216] However, these services and the clergy who perform them play only a minor role in Scientologists' lives.[304]

The Church's Sunday services begin with the minister giving a short welcoming speech, after which they read aloud the principles of Scientology and oversee a silent prayer. They then read a text by Hubbard and either give their own sermon or play a recording of Hubbard lecturing. The congregation may then ask the minister questions about what they have just heard. Next, prayers are offered, for justice, religious freedom, spiritual advancement, and for gaining understanding of the Supreme Being. Announcements will then be read out and finally the service will end with a hymn or the playing of music.[305] Some Church members regularly attend these services, whereas others go rarely or never.[206] Services can be poorly attended.[306]

There are two main celebrations each year. The first, "the Birthday Event," celebrates Hubbard's birthday each March 13. The second, "the May 9th Event," marks the date on which Dianetics was first published.[307] The main celebrations of these events take place at the Church's Clearwater headquarters, which are filmed and then distributed to other Church centers across the world. On the following weekend, this footage is screened at these centers, so Church members elsewhere can gather to watch it.[308]

Weddings, naming ceremonies, and funerals

At Church wedding services, the two partners are requested to remain faithful and assist each other.[309] These weddings employ Scientological terminology, for instance with the minister asking those being married if they have "communicated" their love to each other and mutually "acknowledged" this.[310] The Church's naming ceremony for infants is designed to help orient a thetan in its new body and introduce it to its godparents.[311] During the ceremony, the minister reminds the child's parents and godparents of their duty to assist the newly reborn thetan and to encourage it towards spiritual freedom.[311]

Church funerals may take place in the home or the chapel. If in the latter, there is a procession to the altar, before which the coffin is placed atop a catafalque.[311] The minister reminds those assembled about reincarnation and urges the thetan of the deceased to move on and take a new body.[311] The formal ordination of ministers features the new minister reading aloud the auditor’s code and the code of Scientologists and promising to follow them.[312] The new minister is then presented with the eight-pronged cross of the Church on a chain.[312]

Rejection of psychology and psychiatry

Scientology is vehemently opposed to psychiatry and psychology.[313][314][315] Psychiatry rejected Hubbard's theories in the early 1950s and in 1951, Hubbard's wife Sara consulted doctors who recommended he "be committed to a private sanatorium for psychiatric observation and treatment of a mental ailment known as paranoid schizophrenia".[316][317] Thereafter, Hubbard criticized psychiatry as a "barbaric and corrupt profession".

Hubbard taught that psychiatrists were responsible for a great many wrongs in the world, saying that psychiatry has at various times offered itself as a tool of political suppression and "that psychiatry spawned the ideology which fired Hitler's mania, turned the Nazis into mass murderers, and created the Holocaust".[316] Hubbard created the anti-psychiatry organization Citizens Commission on Human Rights (CCHR), which operates Psychiatry: An Industry of Death, an anti-psychiatry museum.[316]

From 1969, CCHR has campaigned in opposition to psychiatric treatments, electroconvulsive shock therapy, lobotomy, and drugs such as Ritalin and Prozac.[318] According to the official Church of Scientology website, "the effects of medical and psychiatric drugs, whether painkillers, tranquilizers or 'antidepressants', are as disastrous" as illegal drugs.[200]

Organization

The Church of Scientology

The Church is headquartered at the Flag Land Base in Clearwater, Florida.[319] This base covers two million square feet and comprises about 50 buildings.[320] The Church operates on a hierarchical and top-down basis,[321] being largely bureaucratic in structure.[322] It claims to be the only true voice of Scientology.[323] The internal structure of Scientology organizations is strongly bureaucratic with a focus on statistics-based management.[324] Organizational operating budgets are performance-related and subject to frequent reviews.[324]

By 2011, the Church was claiming over 700 centres in 65 countries.[325] Smaller centres are called "missions."[326] The largest number of these are in the U.S., with the second largest number being in Europe.[327] Missions are established by missionaries, who in Church terminology are called "mission holders."[328] Church members can establish a mission wherever they wish, but must fund it themselves; the missions are not financially supported by the central Church organization.[329] Mission holders must purchase all of the necessary material from the Church; as of 2001, the Mission Starter Pack cost $35,000.[330]

Each mission or Org is a corporate entity, established as a licensed franchise, and operating as a commercial company.[331] Each franchise sends part of its earnings, which have been generated through beginner-level auditing, to the International Management.[332] Bromley observed that an entrepreneurial incentive system pervades the Church, with individual members and organisations receiving payment for bringing in new people or for signing them up for more advanced services.[333] The individual and collective performances of different members and missions are gathered, being called "stats."[334] Performances that are an improvement on the previous week are termed "up stats;" those that show a decline are "down stats."[335]

According to leaked tax documents, the Church of Scientology International and Church of Spiritual Technology in the US had a combined $1.7 billion in assets in 2012, in addition to annual revenues estimated at $200 million a year.[336]

Internal organization

The Sea Org is the Church's primary management unit,[333] containing the highest ranks in the Church hierarchy.[324] Its members sign up to a "billion-year contract" to serve the Church.[333]

The Church of Scientology International (CSI) co-ordinates all other branches.[327] In 1982, it founded the Religious Technology Centre to oversee the application of its methods.[337] Missionary activity is overseen by the Scientology Missions International, established in 1981.[328]

The Rehabilitation Project Force (RPF) is a controversial part of the Scientology "justice" system.[338] When Sea Org members are found guilty of a violation, they are assigned to the RPF.[338] The RPF involves a daily regimen of five hours of auditing or studying, eight hours of work, often physical labor, such as building renovation, and at least seven hours of sleep.[338] Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley state that scholars and observers have come to radically different conclusions about the RPF and whether it is "voluntary or coercive, therapeutic or punitive".[338] The Church of Scientology has been criticized for having children as young as twelve on the RPF, for forced labor and denial of access to their parents as a violation of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.[339]

The Office of Special Affairs or OSA (formerly the Guardian's Office) is a department of the Church of Scientology which has been characterized as a non-state intelligence agency.[340][341][342] It has targeted critics of the organization for "dead agent" operations, which is mounting character assassination operations against perceived enemies.[343]

A 1990 article in the Los Angeles Times reported that in the 1980s the Scientology organization more commonly used private investigators, including former and current Los Angeles police officers, to give themselves a layer of protection in case embarrassing tactics were used and became public.[344]

The Church of Spiritual Technology (CST) has been described as the "most secret organization in all of Scientology".[345] Shelly Miscavige, wife of leader David Miscavige, who hasn't been seen in public since 2007, is said to be held at a CST compound in Twin Peaks, California.[346][347]

Scientology operates hundreds of Churches and Missions around the world.[348] This is where Scientologists receive introductory training, and it is at this local level that most Scientologists participate.[348] Churches and Missions are licensed franchises; they may offer services for a fee provided they contribute a proportion of their income and comply with the Religious Technology Center (RTC) and its standards.[348][349]

Promotional material

The Church employs a range of media to promote itself and attract converts.[350] Hubbard promoted Scientology through a vast range of books, articles, and lectures.[197] The Church publishes several magazines, including Source, Advance, The Auditor, and Freedom.[194] It has established a publishing press, New Era,[351] and the audiovisual publisher Golden Era.[352] The Church has also used the Internet for promotional purposes.[353] The Church has employed advertising to attract potential converts, including in high-profile locations such as television ads during the 2014 and 2020 Super Bowls.[354]

The Church has long used celebrities as a means of promoting itself, starting with Hubbard's "Project Celebrity" in 1955 and followed by its first Scientology Celebrity Centre in 1969.[355] There are now at least 8 Celebrity Centres.[356] In 1955, Hubbard created a list of 63 celebrities targeted for conversion to Scientology.[357] Prominent celebrities who have joined the Church include John Travolta, Tom Cruise, Kirstie Alley, Nancy Cartwright, and Juliette Lewis.[358] The Church uses celebrity involvement to make itself appear more desirable,[359] with its Celebrity Centres described as places where famous people can work on their spiritual development without disruption from fans or the press.[360] This pursuit of celebrity involvement has been compared to that of other religious organizations like the Church of Satan, Transcendental Meditation, ISKCON, and the Kabbalah Centre.[360]

Social outreach

The applicability of Hubbard's teachings also led to the formation of secular organizations focused on fields such as drug abuse awareness and rehabilitation, literacy, and human rights.[361] Several Scientology organizations promote the use of Scientology practices as a means to solve social problems. Scientology began to focus on these issues in the early 1970s, led by Hubbard. The Church of Scientology developed outreach programs to fight drug addiction, illiteracy, learning disabilities and criminal behavior. These have been presented to schools, businesses and communities as secular techniques based on Hubbard's writings.[362]

The Church places emphasis on impacting society through a range of social outreach programs.[363] To that end it has established a network of organizations involved in humanitarian efforts,[56] most of which operate on a not-for-profit basis.[192] These endeavor's reflect Scientology's lack of confidence in the state's ability to build a just society.[364] Launched in 1966, Narconon is the Church's drug rehabilitation program, which employs Hubbard's theories about drugs and treats addicts through auditing, exercise, saunas, vitamin supplements, and healthy eating.[365] Criminon is the Church's criminal rehabilitation programme.[192][348] Its Applied Scholastics program, established in 1972, employs Hubbard's pedagogical methods to help students.[366][367] The Way to Happiness Foundation promotes a moral code written by Hubbard, to date translated into more than 40 languages.[367] Narconon, Criminon, Applied Scholastics, and The Way to Happiness operate under the management banner of Association for Better Living and Education.

The World Institute of Scientology Enterprises (WISE) applies Scientology practices to business management.[367] The most prominent training supplier to make use of Hubbard's technology is Sterling Management Systems.[367]

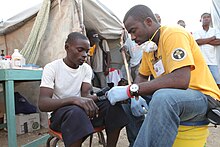

Hubbard devised the Volunteer Minister Program in 1973.[368] Wearing distinctive yellow shirts, the Church's Volunteer Ministers offer help and counselling to those in distress; this includes the Scientological technique of providing "assists".[368] After the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack in New York City, Volunteer Ministers were on the site of Ground Zero within hours of the attack, assisting the rescue workers; Scientology was thus the only non-traditional religion offering pastoral care at that location.[369] Accounts of the Volunteer Ministers' effectiveness have been mixed, and touch assists are not supported by scientific evidence.[370][371][372] The Church's critics regard this outreach as merely a public relations exercise.[363]

The Church employs its Citizens Commission on Human Rights to combat psychiatry,[332] while Scientologists Taking Action Against Discrimination (STAND) does public relations for Scientology and Scientologists.[373] The Church's National Commission on Law Enforcement and Human Rights targets what it perceives as abusive acts conducted by governmental and inter-governmental organizations like the IRS, Department of Justice, Central Intelligence Agency, and Interpol.[332][316] Through these projects, the Church sees itself as "clearing the planet," seeking to return humanity to its natural state of happiness.[374]

Responses to opponents

The Church regards itself as the victim of media and governmental persecution,[375] and the scholar of religion Douglas Cowan observed that "claims to systematic persecution and harassment" are part of the Church's culture.[376] In turn, Urban noted the Church has "tended to respond very aggressively to its critics, mounting numerous lawsuits and at times using extralegal means to respond to those who threaten it."[375] The Church has often responded to criticism by targeting the character of their critic.[377] The Church's approach to targeting their critics has often generated more negative attention for their organization,[378] with Lewis commenting that the Church "has proven to be its own worst enemy" in this regard.[184]

The Church has a reputation for litigiousness stemming from its involvement in a large number of legal conflicts.[379] Barrett characterised the Church as "one of the most litigious religions in the world".[180] It has conducted lawsuits against governments, organizations, and individuals, both to counter criticisms made against it and to gain legal recognition as a religion.[380] Its efforts to achieve the latter have also facilitated other minority groups to doing the same.[381] The Church's litigiousness has been compared to that of the Jehovah's Witnesses during the first half of the 20th century.[194]

Suppressive Persons and Fair Game

Those deemed hostile to the Church, including ex-members, are labelled "Suppressive Persons" or SPs.[382] Hubbard maintained that 20 percent of the population would be classed as "suppressive persons" because were truly malevolent or dangerous: "the Adolf Hitlers and the Genghis Khans, the unrepentant murderers and the drug lords".[383][384] If the Church declares that one of its members is an SP, all other Church members are forbidden from further contact with them, an act it calls "disconnection".[378] Any member breaking this rule is labelled a "Potential Trouble Source" (PTS) and unless they swiftly cease they can be labelled an SP themselves.[385][386][387]

In an October 1968 letter to members, Hubbard wrote about a policy called "Fair Game" which was directed at SPs and other perceived threats to the Church.[149][28] Here he stated that these individuals "may be deprived of property of injured by any means by any Scientologist without any discipline of the Scientologists. May be tricked, sued or lied to or destroyed".[382] Following strong criticism, the Church formally ended Fair Play a month later, with Hubbard stating that he had never intended "to authorize illegal or harassment type acts against anyone."[388] The Church's critics and some scholarly observers argue that its practices reflect that the policy remains in place.[389] Stacey Brooks Young, a former member of the Church's Office of Special Affairs, stated in court that "practices which were formerly called 'Fair Game' continue to be employed, although the term 'Fair Game' is no longer used."[388]

Hubbard and his followers targeted many individuals as well as government officials and agencies, including a program of illegal infiltration of the IRS and other U.S. government agencies during the 1970s.[27][28] They also conducted private investigations, character assassination and legal action against the organization's critics in the media.[27] The policy remains in effect and has been defended by the Church of Scientology as a core "religious practice".[390][391][392]

The Ethics system regulates member behavior,[324] and Ethics officers are present in every Scientology organization. Ethics officers ensure "correct application of Scientology technology" and deal with "behavior adversely affecting a Scientology organization's performance", ranging from "Errors" and "Misdemeanors" to "Crimes" and "Suppressive Acts", as those terms defined by Scientology.[338]

Freezone Scientology

The term "Freezone" is used for the large but loose grouping of Scientologists who are not members of the Church of Scientology.[393] Those within it are sometimes called "Freezoners."[394] Some of those outside the Church prefer to describe their practices as "Independent Scientology" because of the associations that the term "Freezone" has with Ron's Org and the innovations developed by Robertson;[395] "Independent Scientology" is a more recent term than "Freezone".[396]

Key to the Freezone is what scholar of religion Aled Thomas called its "largely unregulated and non-hierarchical environment".[397] Within the Freezone there are many different interpretations of Scientology;[398] Thomas suggested Freezone Scientologists were divided between "purists" who emphasise loyalty to Hubbard's teachings and those more open to innovation.[399] Freezoners typically stress that Scientology as a religion is different from the Church of Scientology as an organization, criticising the latter's actions rather than their beliefs.[400] They often claim to be the true inheritors of Hubbard's teachings,[401] maintaining that Scientology's primary focus is on individual development and that that does not require a leader or membership of an organization.[400] Some Freezoners argue that auditing should be more affordable than it is as performed by the Church,[400] and criticise the Church's lavish expenditure on Org buildings.[402]

The Church has remained hostile to the Freezone,[403] regarding it as heretical.[404] It refers to non-members who either practice Scientology or simply adopt elements of its technology as "squirrels,"[405] and their activities as "squirreling."[232] The term "squirrels" was coined by Hubbard and originally referred only to non-Scientologists using its technology.[400] The Church also maintains that any use of its technology by non-Church members is dangerous as they may not be used correctly.[406] Freezone Scientologists have also accused the Church of "squirrelling,"[396] maintaining that it has changed Hubbard's words in various posthumous publications.[407] Lewis has suggested that the Freezone has been fuelled by some of the Church's policies, including Hubbard's tendency to eject senior members whom he thought could rival him and the Church's "suppressive persons" policy which discouraged rapprochement with ex-members.[408]

Freezone Groups

The term "Free Zone" was first coined in 1984 by Bill Robertson, an early associate of Hubbard's.[409] That year, Robertson founded Ron's Org, a loose federation of Scientology groups operating outside the Church.[410] Headquartered in Switzerland, Ron's Org has affiliated centers in Germany, Russia, and other former parts of the Soviet Union.[411] Robertson claimed that he was channelling messages from Hubbard after the latter's death, through which he discovered OT levels above the eight then being offered by the Church.[412] Although its founding members were formerly part of the Church, as it developed most of those who joined had had no prior involvement in the Church.[413] Another non-Church group was the Advanced Ability Center, founded by David Mayo in the Santa Barbara area. The Church eventually succeeded in shutting it down.[411] In 2012, a Scientology center in Haifa, Israel, defected from the Church.[411]

As well as these organizations, there are also small groups of Scientologists outside the Church who meet informally.[395] Some avoid establishing public centers and communities for fear of legal retribution from the Church.[414] There are also Free Zone practitioners who practice what Thomas calls a "very individualized form of Scientology,"[190] encouraging innovation with Hubbard's technology.[415]

Controversies

The Church of Scientology is a highly controversial organization. A first point of controversy was its challenge of the psychotherapeutic establishment. Another was a 1991 Time magazine article that attacked the organization, which responded with a major lawsuit that was rejected by the court as baseless early in 1992. A third is its religious tax status in the United States, as the IRS granted the organization tax-exempt status in 1993.[418]

It has been in conflict with the governments and police forces of many countries (including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada,[419] France[420] and Germany).[14][421][422][423][424] It has been one of the most litigious religious movements in history, filing countless lawsuits against governments, organizations and individuals.[425]

Reports and allegations have been made, by journalists, courts, and governmental bodies of several countries, that the Church of Scientology is an unscrupulous commercial enterprise that harasses its critics and brutally exploits its members.[422][423] A considerable amount of investigation has been aimed at the organization, by groups ranging from the media to governmental agencies.[422][423]

The controversies involving the Church of Scientology, some of them ongoing, include: