Sam Manekshaw

Sam Manekshaw | |

|---|---|

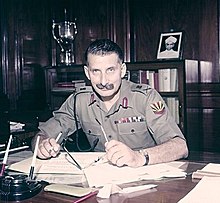

Manekshaw pictured wearing his general's insignia | |

| 7th Chief of the Army Staff, India | |

| In office 8 June 1969 – 15 January 1973 | |

| President | V. V. Giri Mohammad Hidayatullah |

| Prime Minister | Indira Gandhi |

| Preceded by | General P. P. Kumaramangalam |

| Succeeded by | General Gopal Gurunath Bewoor |

| 9th General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Eastern Command | |

| In office 16 November 1964 – 8 June 1969 | |

| Preceded by | Lt Gen P P Kumaramangalam |

| Succeeded by | Lt Gen Jagjit Singh Aurora |

| 9th General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Western Command | |

| In office 4 December 1963 – 15 November 1964 | |

| Preceded by | Lt Gen Daulet Singh |

| Succeeded by | Lt Gen Harbaksh Singh |

| 2nd General Officer Commanding, IV Corps | |

| In office 2 December 1962 – 4 December 1963 | |

| Preceded by | Lt Gen Brij Mohan Kaul |

| Succeeded by | Lt Gen Manmohan Khanna |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Sam Hormusji Framji Jamshedji Manekshaw 3 April 1914 Amritsar, Punjab Province, British India |

| Died | 27 June 2008 (aged 94) Wellington, Tamil Nadu, India |

| Resting place | Parsi Zoroastrian Cemetery, Ooty, Tamil Nadu, India |

| Spouse | Silloo Bode |

| Nickname | "Sam Bahadur"[1] |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | British India India |

| Branch/service | British Indian Army Indian Army |

| Years of service | 1934 – 2008[a] |

| Rank | Field Marshal |

| Unit | 12th Frontier Force Regiment 8th Gorkha Rifles |

| Commands | |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | |

| Service number | IC-14 |

Field Marshal Sam Hormusji Framji Jamshedji Manekshaw[3] MC (3 April 1914 – 27 June 2008), also known as Sam Bahadur ("Sam the Brave"), was an Indian Army general officer who was the chief of the army staff during the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, and the first Indian to be promoted to the rank of field marshal. His active military career spanned four decades, beginning with service in World War II.

Manekshaw joined the first intake of the Indian Military Academy at Dehradun in 1932. He was commissioned into the 4th Battalion, 12th Frontier Force Regiment. In World War II, he was awarded the Military Cross for gallantry. Following the Partition of India in 1947, he was reassigned to the 8th Gorkha Rifles. Manekshaw was seconded to a planning role during the 1947 Indo-Pakistani War and the Hyderabad crisis, and as a result, he never commanded an infantry battalion. He was promoted to the rank of brigadier while serving at the Military Operations Directorate. He became the commander of 167 Infantry Brigade in 1952 and served in this position until 1954 when he took over as the director of military training at the Army Headquarters.

After completing the higher command course at the Imperial Defence College, he was appointed the general officer commanding of the 26th Infantry Division. He also served as the commandant of the Defence Services Staff College. In 1962, he was accused in a politically motivated treason trial, he was eventually found innocent but thus could not serve in the 1962 war. In 1963, Manekshaw was promoted to the rank of army commander and took over Western Command, then was transferred in 1964 to Eastern Command. In this role, in 1967, he was involved in the first Indian victory against a Chinese offensive during the Nathu La and Cho La clashes.

Manekshaw was awarded the Padma Bhushan, the third highest Indian civilian award, in 1968 for responding to the insurgencies in Nagaland and Mizoram. Manekshaw became the seventh chief of army staff in 1969. Under his command, Indian forces providing them with arms and ammunitions to fight against the strong regular army of Pakistan in the Bangladesh-Pakistani War of 1971, which led to the creation of Bangladesh in December 1971. He was awarded the Padma Vibhushan, the second highest civilian award of India, in 1972 for his services to the nation. Manekshaw was promoted to the rank of field marshal in January 1973, the first of only two Indian officers to be ever promoted to this rank. He retired on 15 January 1973, a date celebrated as Army Day in India. Manekshaw died on 27 June 2008 due to complications from pneumonia.

Early life and family

Sam Manekshaw was born on 3 April 1914 in Amritsar to Hormizd[b] (1871–1964), a doctor, and Hilla, née Mehta (1885–1970). Both of his parents were Parsis who had moved to Amritsar from the city of Valsad in coastal Gujarat.[4][5] Manekshaw's parents had left Mumbai in 1903 for Lahore, where his father was going to start practising medicine. However, when their train halted at Amritsar station, Hilla found it impossible to travel any further due to her advanced pregnancy.[6] After Hilla had recovered from child birth, the couple decided to stay in Amritsar, where Hormizd soon set up a clinic and pharmacy. The couple had four sons (Fali, Jan, Sam and Jami) and two daughters (Cilla and Sheru). Manekshaw was their fifth child and third son.[7]

During World War II, Hormizd had served in the British Indian Army as a captain in the Indian Medical Service (now the Army Medical Corps).[6] Manekshaw's elder brothers Fali and Jan became engineers, while his sisters Cilla and Sheru became teachers. Manekshaw's younger brother Jami became a doctor and served in the Royal Indian Air Force as a medical officer. In 1948, Jami became the first Indian to be awarded air surgeon's wings from Naval Air Station Pensacola in the United States, after completing a training course there. Jami joined his elder brother, Sam, in becoming a flag officer, and retired as an air vice marshal in the Indian Air Force.[6]

Education

Manekshaw completed his primary schooling in Punjab, and then joined Sherwood College, Nainital.[8] In 1931, he passed his senior high school examinations with distinction. He then asked his father to send him to London to study medicine, but his father refused as he was not old enough. His father was already supporting Sam's elder brothers who were studying engineering in London.[9] Manekshaw instead enrolled at the Hindu Sabha College (now the Hindu College, Amritsar) and graduated in April 1932.[10]

A formal notification for the entrance examination to enrol in the newly established Indian Military Academy (IMA) was issued in the early months of 1932. Examinations were scheduled for June or July.[11] In an act of rebellion against his father's refusal to send him to London, Manekshaw applied for a place and sat for the entrance exams in Delhi. On 1 October 1932, he was one of the fifteen cadets to be selected through an open competition,[c] and placed sixth in the order of merit.[11]

Indian Military Academy

Manekshaw was part of the first batch of cadets at the IMA. Called "The Pioneers", this batch also included Smith Dun and Muhammad Musa Khan, the future commanders-in-chief of Burma and Pakistan, respectively. Although the academy was inaugurated on 10 December 1932, the cadets' military training commenced on 1 October 1932.[11] As an IMA cadet, Manekshaw went on to achieve a number of distinctions: the only one to attain the rank of field marshal.[11] The commandant of the Academy during this period was Brigadier Lionel Peter Collins. Manekshaw was almost suspended from the Academy when he went to Mussoorie for a holiday with Kumar Jit Singh (the Maharaja of Kapurthala) and Haji Iftikhar Ahmed, and did not return in time for the morning drills.[12]

Of the 40 cadets inducted into the IMA, only 22 completed the course; they were commissioned as second lieutenants on 1 February 1935.[13] Some of his batchmates were Dewan Ranjit Rai; Mohan Singh, the founder of the Indian National Army; Melville de Mellow, a famous radio presenter; and two generals of the Pakistani Army, Mirza Hamid Hussain and Habibullah Khan Khattak. Many of Manekshaw's batchmates were captured by Japan during World War II and would fight in the Indian National Army, which mostly drew its troops from Indian prisoners of war in Axis camps.[14] Tikka Khan, who would later join the Pakistani Army during the Partition, was Manekshaw's junior at the IMA by five years and also his boxing partner.[15]

Military career

When Manekshaw was commissioned, it was standard practice for newly commissioned Indian officers to be initially assigned to a British regiment before being sent to an Indian unit. Manekshaw thus joined the 2nd Battalion, Royal Scots, stationed at Lahore. He was later posted to the 4th Battalion, 12th Frontier Force Regiment (4/12 FF), stationed in Burma.[16][17] On 1 May 1938, he was appointed quartermaster of his company.[18] Already fluent in Punjabi, Hindi, Urdu, English and his native language Gujarati, in October 1938 Manekshaw qualified as a Higher Standard army interpreter in Pashto.[19]

World War II

There was a shortage of qualified officers at the outbreak of the war, officers were thus promoted without having served for the minimum period required for a promotion. Therefore, for the first two years of the conflict, Manekshaw was temporarily appointed to the ranks of captain and major before being promoted to the substantive rank of captain on 4 February 1942.[20]

Battle of Pagoda Hill

Manekshaw saw action in Burma during the 1942 campaign at the Sittang River with 4/12 FF,[21] and was recognised for his bravery in the battle. During the fighting around Pagoda Hill, a key position on the left of the Sittang bridgehead, he led his company in a counter-attack against the invading Imperial Japanese Army. Despite suffering 30% casualties, the company managed to achieve its objective, partly because of the aid received from Captain John Niel Randle's company.[22] After capturing the hill, Manekshaw was hit by a burst of light machine gun fire, and was severely wounded in the stomach.[23] While observing the battle, Major General David Cowan, general officer commanding of the 17th Infantry Division, spotted the wounded Manekshaw and awarded him the Military Cross.[24] This award was made official with the publication of the notification in a supplement to the London Gazette.[25] The citation reads:

This officer was in command of the 'A' Company of his battalion when ordered to counter-attack the Pagoda Hill position, the key hill on the left of the Sittang Bridgehead, which had been captured by the enemy. The counterattack was successful despite 30% casualties, and this was largely due to the excellent leadership and bearing of Captain Manekshaw. This officer was wounded after the position had been captured.[26]

Manekshaw was evacuated from the battlefield by Sher Singh, his orderly, who took him to an Australian surgeon. The surgeon initially declined to treat Manekshaw, saying that he had been too badly wounded. Manekshaw's chances of survival were low, but Sher Singh persuaded the doctor to treat him. Manekshaw regained consciousness, and when the surgeon asked what had happened to him, he replied that he had been "kicked by a mule". Impressed by Manekshaw's sense of humour, the surgeon treated him, removing the bullets from his lungs, liver, and kidneys. Most of his intestines were also removed.[24]

Having recovered from his wounds, Manekshaw attended the eighth staff course at the Command and Staff College in Quetta between 23 August and 22 December 1943. On completion, he was posted as the brigade major of the Razmak Brigade. He served in that post until 22 October 1944, after which he joined the 9th Battalion, 12th Frontier Force Regiment, part of the 14th Army commanded by General William Slim.[24] On 30 October 1944, he received the temporary rank of lieutenant colonel.[20] By the end of the war, he was appointed as a staff officer to the general officer commanding of the 20th Indian Infantry Division, Major General Douglas Gracey.[27] During the Japanese surrender, Manekshaw was appointed to supervise the disarmament of over 10,000 Japanese prisoners of war (POWs). No cases of indiscipline or escape attempts were reported from the camp Manekshaw was in charge of.[28] He was promoted to the acting rank of lieutenant colonel on 5 May 1946, and completed a six-month lecture tour of Australia.[29] From 1945 to 1946, Manekshaw and Yahya Khan were two of the staff officers of Field Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck.[30][31] Manekshaw was promoted to the substantive rank of major on 4 February 1947, and on his return from Australia was appointed a Grade 1 General Staff Officer (GSO1) in the Military Operations (MO) Directorate.[29][32]

Post-independence

Due to the Partition of India in 1947, Manekshaw's unit, the 4th Battalion, 12th Frontier Force Regiment, became part of the Pakistan Army. Manekshaw was therefore reassigned to the 8th Gorkha Rifles.[33][32][34] Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan's first Governor General, also considered the founder of that nation, had reportedly asked Manekshaw to join the Pakistani Army, but Manekshaw had refused.[35][36]

In October 1947, Manekshaw was posted as the commanding officer of the 3rd Battalion, 5 Gorkha Rifles (Frontier Force) (3/5 GR (FF)). Before he had moved on to his new appointment, on 22 October, Pakistani forces infiltrated the Kashmir region, capturing Domel and Muzaffarabad. The following day, the ruler of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, Maharaja Hari Singh, appealed to India for help. On 25 October, Manekshaw accompanied V. P. Menon to Srinagar, where he carried out an aerial survey of the situation in Kashmir. On the same day, they flew back to Delhi, where Lord Mountbatten and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru were briefed.[37] On the morning of 27 October, Indian troops were sent to Kashmir to defend Srinagar from the Pakistani forces, who had reached the city's outskirts. Manekshaw's assignment as the commander of 3/5 GR (FF) was cancelled, and he was posted to the MO Directorate. As a consequence of the Kashmir dispute and the annexation of Hyderabad (whose events he briefed Sardar Patel on), Manekshaw never commanded a battalion. During his term at the MO Directorate, he was promoted to colonel, then brigadier. He was then appointed the director of military operations (DMO).[38]

Manekshaw was one of the three army officers who represented India at the 1949 Karachi Conference. The Conference resulted in the Karachi Agreement and the Ceasefire Line (which evolved into the Line of Control). The other two army officers at the conference were Lt. Gen. S. M. Shrinagesh and Maj. Gen. KS Thimayya, while the two civilian officers were Vishnu Sahay and HM Patel.[39][40][41]

Manekshaw was promoted to the rank of colonel on 4 February 1952,[42][d] and in April was appointed the commander of 167 Infantry Brigade, headquartered at Firozpur.[42] On 9 April 1954, he was appointed the director of military training at Army Headquarters.[43] He was appointed the commandant of the Infantry School at Mhow on 14 January 1955, and also became the colonel of both the 8th Gorkha Rifles and the 61st Cavalry.[44] During his tenure as the commandant of the Infantry School, he discovered that the training manuals were outdated, and was instrumental in revamping them to be consistent with the tactics employed by the Indian Army.[45] He was promoted to the substantive rank of brigadier on 4 February 1957.[46]

General officer

In 1957, he went to the Imperial Defence College, London, to attend a year long higher command course.[47] On his return, he was appointed the general officer commanding (GOC) 26th Infantry Division on 20 December 1957, with the acting rank of major general.[48] When he commanded the division, Gen. K. S. Thimayya was the chief of the army staff (COAS), and Krishna Menon the defence minister. During a visit to Manekshaw's division, Menon asked him what he thought of Thimayya. Manekshaw replied that it was improper to evaluate his superior, and told Menon not to ask anybody again. This annoyed Menon, and he told Manekshaw that if he wanted to, he could sack Thimayya, to which Manekshaw replied, "You can get rid of him. But then I will get another."[49][50]

Manekshaw was promoted to substantive major general on 1 March 1959.[51] On 1 October, he was appointed the Commandant of the Defence Services Staff College, Wellington,[52] where he was caught up in a controversy that almost ended his career. In May 1961, Thimayya resigned as the COAS, and was succeeded by General Pran Nath Thapar. Earlier in the year, Major General Brij Mohan Kaul had been promoted to lieutenant general and appointed the Quarter Master General by Menon. The appointment was made against the recommendation of Thimayya, who resigned as a result. Kaul was made the chief of general staff (CGS), the second highest appointment at Army Headquarters after the COAS. Kaul cultivated a close relationship with Nehru and Menon and became even more powerful than the COAS. This was met with disapproval by senior army officials, including Manekshaw, who argued against the interference of the political leadership in the administration of the army. This led him to be marked as an anti-national.[50]

Kaul sent informers to spy on Manekshaw[53] who, as a result of the information gathered, was charged with sedition, and subjected to a court of inquiry. The charges against him were that he was more loyal to the Queen and the Crown than to India, because he had not removed portraits of the Queen and British military and civilian officers from the College and his office.[54][55] The court, presided over by the general officer commanding-in-chief (GOC-in-C) of Western Command, Lt. Gen. Daulet Singh, exonerated Manekshaw as no evidence against him was found.[56][57] Before a formal 'no case to answer' could be announced, the Sino-Indian War broke out; Manekshaw was not able to participate because of the court proceedings. The Indian Army was defeated in the war, for which Kaul and Menon were held primarily responsible, both were sacked. In November 1962, Nehru asked Manekshaw to take over the command of IV Corps. Manekshaw told Nehru that the court action against him was a conspiracy, and that his promotion had been due for almost eighteen months; Nehru apologised.[50] Shortly after, on 2 December 1962, Manekshaw was promoted to acting lieutenant general and appointed the GOC of IV Corps at Tezpur.[58]

Soon after taking charge, Manekshaw reached the conclusion that poor leadership had been a significant factor in IV Corps' failure in the war with China. He felt the first course of action was to improve the morale of his soldiers. Manekshaw identified the root cause of the low morale to be panicked withdrawals, ordered without allowing the soldiers to fight back. He ordered there to be no more retreats without his written permission.[59] The next task Manekshaw took up was to reorganise the troops in the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA), where he alleviated the shortages of equipment, accommodation and clothing.[60] Analyst Srinath Raghavan noted that Corps Commander Manekshaw and COAS Jayanto Nath Chaudhuri had delayed moving into the NEFA region until the end of 1963, in order to avoid provoking a new Chinese offensive.[61][62]

Promoted to substantive lieutenant general on 20 July 1963, Manekshaw was appointed an army commander on 5 December, taking command of Western Command as the GOC-in-C.[63][64] Defence analyst Ajai Shukla, citing Anit Mukherjee, states that Western Command troops were reported to be moving from Punjab to Delhi after Nehru's death. This movement was seen as the precursor to a coup by the civilian establishment, while the army said it was moving in troops to manage the large crowds expected at Nehru's funeral.[65][66] As a result, on 16 November 1964, Manekshaw was transferred from Shimla to Calcutta as the GOC-in-C Eastern Command.[67] There he responded to the insurgencies in Nagaland and Mizoram, for which he was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1968.[68]

Nathu La and Cho La clashes

In 1967, five years after the War of 1962, China decided to capture four critical posts in Sikkim: Nathu La, Jelep La, Sebu La and Cho La. These posts were strategically valuable, as they oversaw the Chicken's Neck, the small strip of land which provides access to Northeast India.[69] Major General Sagat Singh decided not to retreat following the Chinese attack.[70] Manekshaw endorsed this initiative by Singh and remarked: "I am afraid they are enacting Hamlet without the Prince. I will now tell you how I intend to deal with this."[71][72][73] The conflict ended in Indian victory following the Chinese withdrawal from the area.[74]

Chief of army staff

Gen. P. P. Kumaramangalam retired as the chief of army staff (COAS) in June 1969. Manekshaw was appointed as the eighth chief of the army staff on 8 June 1969.[75] During his tenure, he was instrumental in stopping a plan to reserve quotas in the army for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Though he was a Parsi, a minority in India, Manekshaw felt reservation would compromise the ethos of the army and believed all must be given an equal chance.[76]

In his capacity as the COAS, Manekshaw once visited a battalion of the 8 Gorkha Rifles in July 1969. He asked an orderly if he knew the name of his chief. The orderly replied that he did, and on being asked to name the chief, he said "Sam Bahadur" (lit. "Sam the Brave").[e] This eventually became Manekshaw's nickname.[77] During this period, there were suspicions that Manekshaw would lead a coup and impose martial law. Indira Gandhi had asked him if he intended to coup, Manekshaw had denied.[78] Once, an American diplomat, in the presence of Kenneth Keating, the US ambassador to India, had asked Manekshaw when he was going to stage a coup. Manekshaw reportedly said, "As soon as General Westmoreland takes over your country".[79]

Bangladesh Liberation War 1971

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 was sparked by the Bangladesh Liberation war, a conflict between the traditionally dominant West Pakistanis and the East Pakistanis who were a majority of the population but lacked representation. In 1970, East Pakistanis called for Bengali autonomy, but the Pakistani government failed to meet these demands. In early 1971, opinion shifted towards secession in East Pakistan. In March, the Pakistan Armed Forces launched a fierce campaign to curb the secessionists, whose members included soldiers and police from East Pakistan. Thousands of East Pakistanis died, and nearly ten million refugees fled to West Bengal, an adjacent Indian state. In April, India decided to intervene militarily to create Bangladesh.[80]

During a cabinet meeting towards the end of April, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi asked Manekshaw if he was prepared to go to war with Pakistan. He replied that most of his armoured and infantry divisions were deployed elsewhere, only twelve of his tanks were combat-ready, and they would be competing for rail carriages with the grain harvest. He also pointed out that the Himalayan passes would soon open up with the forthcoming monsoon, which would result in heavy flooding.[81] After the cabinet had left the room, Manekshaw offered to resign; Gandhi declined and instead sought his advice. He said he could guarantee victory if she would allow him to handle the conflict on his own terms, and set a date for its initiation; Gandhi agreed.[82]

Following the strategy planned by Manekshaw, the army launched several preparatory operations in East Pakistan, including training and equipping the Mukti Bahini, a local militia group of Bengali nationalists. About three brigades of regular Bangladeshi troops were trained, and 75,000 guerrillas were trained and equipped with arms and ammunition. These forces were used to harass the Pakistani Army forces stationed in East Pakistan in the lead-up to the war.[83]

The war started officially on 3 December 1971, when Pakistani aircraft bombed Indian Air Force bases in western India. The Army Headquarters under Manekshaw's leadership formulated the following strategy: II Corps commanded by Lt. Gen. Tapishwar Narain Raina would enter from the west; IV Corps commanded by Lt. Gen. Sagat Singh would enter from the east; XXXIII Corps commanded by Lt. Gen. Mohan L. Thapan would enter from the north; and the 101 Communication Zone Area commanded by Maj. Gen. Gurbax Singh would provide support from the northeast. This strategy was to be executed by Eastern Command under Lt. Gen. Jagjit Singh Aurora. Manekshaw instructed Lt. Gen. J.F.R. Jacob, chief of staff, Eastern Command, to inform the Indian prime minister that orders were being issued for the movement of troops from Eastern Command. The following day, the Indian Navy and Air Force also initiated full-scale operations on both the eastern and western fronts.[84]

As the war progressed, India captured most of the strategic positions and isolated the Pakistani forces, who started to surrender or withdraw.[85] The UN Security Council assembled on 4 December 1971 to discuss the situation. After lengthy discussions on 7 December, the United States put forward a resolution for an "immediate cease-fire and withdrawal of troops". While supported by the majority, the USSR vetoed it twice, and because of Pakistani atrocities in Bengal, the United Kingdom and France abstained.[86] On 8 December, a C141 American cargo plane was seen unloading arms & other equipment at Karachi. Manekshaw prevented any further supplies by summoning the military attache at the US embassy in India and asking him to stop the drops which were in contravention of US public policy.[87][88][89]

Indian forces have surrounded you. Your Air Force is destroyed. You have no hope of any help from them. Chittagong, Chalna and Mangla ports are blocked. Nobody can reach you from the sea. Your fate is sealed. The Mukti Bahini and the people are all prepared to take revenge for the atrocities and cruelties you have committed...Why waste lives? Don't you want to go home and be with your children? Do not lose time; there is no disgrace in laying down your arms to a soldier. We will give you the treatment befitting a soldier[.]

— Manekshaw's first radio message to the Pakistani troops on 9 December 1971[90]

Manekshaw addressed the Pakistani troops by radio broadcast on 9, 11 and 15 December, assuring them that they would receive honourable treatment from the Indian troops if they surrendered. The last two broadcasts were delivered as replies to messages from the Pakistani commanders Maj. Gen. Rao Farman Ali and Lt. Gen. Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi to their troops. These broadcasts had a demoralising effect; they convinced the Pakistani troops of the futility of further resistance and led to their decision to surrender.[85]

On 11 December, Ali messaged the United Nations requesting a ceasefire, but it was not authorised by President Yahya Khan, and the fighting continued. Following several discussions and consultations, and subsequent attacks by the Indian forces, Khan decided to stop the war in order to avoid any additional Pakistani casualties.[85] The actual decision to surrender was taken by Niazi on 15 December and was conveyed to Manekshaw through the United States Consul General in Dhaka via Washington.[91] Manekshaw replied that he would stop the war only if the Pakistani troops surrendered to their Indian counterparts by 9 AM on 16 December. The deadline was extended to 3 PM on the same day at Niazi's request, and the instrument of surrender was formally signed on 16 December 1971 by Lt. Gen. Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi.[90]

When the prime minister asked Manekshaw to go to Dhaka and accept the surrender of Pakistani forces, he declined, saying that the honour should go to the GOC-in-C Eastern Command, Lt. Gen. Jagjit Singh Aurora.[16] Concerned about maintaining discipline in the aftermath of the conflict, Manekshaw issued strict instructions forbidding looting and rape and stressed the need to respect and stay away from women. As a result, according to Singh, cases of looting and rape were negligible.[92] While addressing his troops on the matter, Manekshaw was quoted as saying: "When you see a Begum (Muslim woman), keep your hands in your pockets, and think of Sam."[92]

The war lasted 12 days and saw 93,000 Pakistani soldiers taken prisoner. It ended with the unconditional surrender of East Pakistan and resulted in the creation of Bangladesh.[93] In addition to the prisoners of war (POWs), Pakistan suffered 6,000 casualties against India's 2,000.[94] After the war, Manekshaw ensured good conditions for the POWs, but was criticised for treating them like "sons in law" by the cabinet.[95][96] Singh recounts that in some cases he addressed them personally and talked to them privately, with just his aide-de-camp for company, while they shared a cup of tea. He made provisions for the prisoners to be supplied with the copies of the Quran, and allowed them to celebrate festivals and receive letters and parcels from their loved ones.[93] However, he did not want them to be returned to Pakistan until a peace agreement was concluded, as the POWs numbered about four divisions of soldiers and could be deployed for another war.[97] The Pakistani POWs remained in captivity for several years,[98] used as leverage for Pakistan officially recognizing Bangladesh.[99]

Manekshaw was India's official representative for the negotiations held on 28 November 1972 to demarcate the Line of Control in Kashmir after the war. Pakistan's representative was General Tikka Khan. The talks broke down due to disagreements on control over parts of Thako Chak and Kaiyan (located in Pakistan's Chicken's Neck), Chhamb and Tortuk.[100] The second round of talks held from 5 to 7 December managed to resolve these issues.[101][102][103]

Promotion to field marshal

After the war, Indira Gandhi decided to promote Manekshaw to the rank of field marshal and appoint him as the chief of defence staff (CDS). However, after several objections from the commanders of the navy and the air force, the appointment was dropped. Because Manekshaw was from the army, there were concerns that the comparatively smaller forces of the navy and air force would be neglected. Moreover, the bureaucrats felt that the appointment might reduce their influence over defence issues.[104] Though Manekshaw was to retire in June 1972, his term was extended by a period of six months, and "in recognition of outstanding services to the Armed Forces and the nation," he was promoted to the rank of field marshal on 1 January 1973.[105] The first Indian Army officer to be so promoted, he was formally conferred with the rank in a ceremony held at the Rashtrapati Bhavan (President's Residence) on 3 January.[106]

Honours and post-retirement

For his service to India, the President of India, VV Giri, awarded Manekshaw the Padma Vibhushan in 1972. Manekshaw retired from active service on 15 January 1973 (celebrated as Army Day in India) after a career of nearly four decades. He moved with his family to Coonoor, the civilian town next to Wellington Cantonment, where he had served as commandant of the Defence Services Staff College early on in his career. Popular with Gorkha soldiers, Nepal fêted Manekshaw as an honorary general of the Nepalese Army in 1972.[2] In 1977, he was awarded the Order of Tri Shakti Patta First Class, an order of knighthood of the Kingdom of Nepal by King Birendra.[107] Following his service in the Indian Army, Manekshaw served as an independent director on the board and, in a few cases, as the chairman of several companies, like Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation, Britannia Industries and Escorts Limited.[2][108]

In May 2007, Gohar Ayub, the son of the Pakistani Field Marshal Ayub Khan, claimed that Manekshaw had sold Indian Army secrets to Pakistan during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 for 20,000 rupees, but his accusations were dismissed by the Indian defence establishment.[109][110]

Although Manekshaw was conferred the rank of field marshal in 1973, it was reported that he was not given the complete allowances he was entitled to. He did not receive these until 2007, when President A. P. J. Abdul Kalam met him in Wellington, and presented him with a cheque for ₹1.3 crore (equivalent to ₹3.9 crore or US$450,000 in 2023)—his arrears of pay for over 30 years.[111][112] Manekshaw was critical of politicians and civilian bureaucrats, and frequently mocked them, asking for example, "whether those of our political masters who have been put in charge of the defence of the country can distinguish a mortar from a motor; a gun from a howitzer; a guerrilla from a gorilla – although a great many in the past have resembled the latter.”[113]

Manekshaw visited hospitalised soldiers during the Kargil War and was cited by COAS Ved Prakash Malik, the commander during the war, as his icon.[114]

Personal life and death

Manekshaw married Silloo Bode on 22 April 1939 in Bombay. The couple had two daughters, Sherry and Maya (later Maja), born in 1940 and 1945 respectively. Manekshaw died of complications from pneumonia at the Military Hospital in Wellington, Tamil Nadu, at 12:30 a.m. on 27 June 2008 at the age of 94.[3] Reportedly, his last words were "I'm okay!"[81] He was buried at the Parsi cemetery in Udhagamandalam (Ooty), Tamil Nadu, with military honours, adjacent to his wife's grave.[115] His funeral lacked governmental representation, which the media argued was a result of the civilian establishment's apathy towards the military, who feared that the military would stage a coup if it became too popular with the citizenry.[116] A national day of mourning was not declared. While this was not a breach of protocol, such commemoration is customary for a leader of national importance.[117][118][119] Bangladesh, however, did pay tribute to Manekshaw on his death.[81] He was survived by two daughters and three grandchildren.[120]

Character

Manekshaw was charismatic and known to be capable of charm.[121][122] He was often described as a gentleman.[123] Like others of his generation, his background in the British army gave him a fondness for some English habits, such as drinking whiskey and wearing his handlebar moustache.[124] His background as a Parsi is sometimes attributed as a factor in his ambition and success.[81] He commanded great loyalty from his troops, particularly the Gorkhas, due to his reputation for personal bravery, fairness and his avoidance of punishments.[125] He came into conflict with politicians, however, because he stood up to their often unreasonable or unethical demands. They also disliked his popularity as they feared the possibility of a military coup. He dealt with politicians' demands through sarcasm, which however was recognised by figures such as Indira Gandhi.[126][3] Manekshaw also did not hesitate from advocating for better strategies than those developed by the civilian establishment, a trait rarely found in the military brass today, according to Admiral Arun Prakash.[127][128]

Legacy and assessment

Vijay Diwas (lit. Victory Day) is celebrated on 16 December every year in honor of the victory achieved under Manekshaw's leadership in 1971. On 16 December 2008, a postage stamp depicting Manekshaw in his field marshal's uniform was released by then President Pratibha Patil.[129]

The Manekshaw Centre in the Delhi Cantonment is named for the field marshal. The centre was inaugurated by the President of India on 21 October 2010.[130][131] The biannual Army Commanders' conference takes place at the centre.[132] The Manekshaw parade ground in Bengaluru is also named after him. The Republic Day celebrations in Karnataka are held at this ground every year.[133] A flyover bridge in Ahmedabad's Shivranjeeni area was named after him in 2008 by the then Chief Minister of Gujarat, Narendra Modi.[134] In 2014, a granite statue was erected in his honour at Wellington, in the Nilgiris district, close to the Manekshaw Bridge on the Ooty–Coonoor road, which had been named after him in 2009.[135][136] His statue is also on the Maneckji Mehta Road in Pune Cantonment. The Centre for Land Warfare Studies, an Indian military think tank, publishes its research papers in a collection called the Manekshaw Papers as a tribute to the field marshal.[137]

Manekshaw has been portrayed in film and fiction. Vicky Kaushal played the role of Manekshaw in the 2023 biopic Sam Bahadur.[138] He is also featured conversing with his Pakistani adversary and former Burma war colleague Tiger Niazi in Salman Rushdie's novel Midnight's Children, in the chapter entitled "Sam and the Tiger".[139]

Soldiers' pay

In 1970, the Armed Forces and the Army in particular had the opportunity for the first time to get their pay determined by the Pay Commission, which set the pay levels for all other government employees. Armed Forces personnel had not been considered for the 1st and 2nd Pay Commissions but were to be considered for the 3rd Pay Commission.[140] Manekshaw convinced the government to apply the 3rd Pay Commission's recommendations for military personnel and set pay scales for them proportionate to their service conditions (termed hazard pay), a practice which continues to this day.[141]

Strategy and doctrine

Manekshaw's strategies during the 1971 war have been considered by analysts to be the precursor to the Indian Cold Start military doctrine, which calls for integrated offensive attacks.[142] Formulated along with his deputies Aurora and Singh, Manekshaw's shock and awe tactic of deploying IV Corps, which was geographically disadvantaged, contributed significantly to the military victory.[143] Analysts consider Manekshaw and Aurora to have created a Blitzkrieg style of warfare which was even more rapid.[144][145][146]

Defence analyst Robert M. Citino noted that the speed of the 1971 campaign had been impressive, but it had taken too much time to mobilise the units involved; its logistics had been rather crude; and it could have run into problems if there had been an air force in East Pakistan. Manekshaw said the following about the campaign: "To say that it was something like what Rommel did would be ridiculous".[147]

General André Beaufre, a French military theorist, had been invited by Manekshaw to analyse the 1971 war. Beaufre had previously observed the Battles of Chumb and Basantar from the Pakistani side.[148][149] Beaufre concluded that the Indian operations on the Eastern Front were maneuver warfare but the operations in and around the Shakargarh bulge had been too slow.[150][151][152]

On 12 October 1966, while on a flight from Delhi to Kolkata, Manekshaw was a co passenger with William K. Hitchcock, the Consul General of the USA in Kolkata. On the flight, Manekshaw talked to Hitchcock about the need for more military involvement in Kashmir and criticized COAS Chaudhuri's decision to not deploy the 300,000 Indian soldiers of Eastern Command in the 1965 War due to fear of a Chinese offensive. Maneksaw also expressed his worries over India's dependence on Soviet defence equipment, and said he would have advocated for India taking a more American friendly stance on the Vietnam War if he had had more power.[153][154]

Procurement

Manekshaw was an advocate for a strong domestic defence industrial base and procurement reforms, which he believed could shorten the long order and delivery cycles of the Indian Armed Forces. He was also a critic of defence equipment imports and over reliance on the Soviet Union and its successor state, Russia.[155] During the 1971 War, Manekshaw managed to urgently procure equipment to achieve numerical superiority and raise new divisions.[156][157] However, he could not make any lasting reforms to the procurement process.[158]

Special operations

After being convinced by Brigadier Bhawani Singh on the need for special operations, Manekshaw approved the plans for the Chachro Raid, which the brigadier had drawn up himself.[159] The raid resulted in the capture of 13,000 square kilometres (5,000 sq mi) of Pakistani territory up to Umerkot in Sindh province, and is considered by analysts to be the most successful operation by an Indian special operations unit.[160][161]

Counter insurgency

While responding to the insurgency in Mizoram in 1966, Manekshaw implemented the policy of merging small villages (termed spatialisation) as a counter insurgency tool. The intended effect was to prevent insurgents from hiding in sparsely populated villages, and to enable safer civilian and military operations. By forcing insurgents to operate out of uninhabited areas, they were denied access to food and supplies; the army also had to patrol a smaller area and did not have to engage in high casualty urban warfare as a result of the policy.[162][163]

See also

Notes

- ^ Manekshaw retired from active service in 1973,[2] however, like U.S. officers, Indian military five-star rank officers hold their rank for life, and are considered to be serving officers until their deaths.

- ^ Hormizd was his Iranian name, for communicating with Indians and Britishers he used the name Hormusji.

- ^ There were 40 vacancies, of which 15 were filled through an open competition, 15 from the ranks of the army and the remaining 10 from the princely state forces.[11]

- ^ In the decade after Independence, due to shortages of qualified officers in the senior ranks, it was common for officers to be promoted before they had completed the usual requisite years of service to advance in rank. Manekshaw received a further 4 year extension in his substantive rank of colonel in 1956 as a result.

- ^ Bahadur was an honorific title bestowed upon princes and victorious military commanders by Mughal emperors, and later by their British successors.

References

- ^ "Sam Manekshaw: Leaders Pay Tribute To India's Greatest General". NDTV. 3 April 2019. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Mehta 2003.

- ^ a b c Pandya 2008.

- ^ Singh 2005, p. 183.

- ^ Sharma 2007, p. 59.

- ^ a b c Singh 2005, p. 184.

- ^ Sood, Maj Gen Shubhi (1 January 2021). Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw. Prabhat Prakashan.

- ^ Hasnain, Lieutenant General Syed Ata (retd.) (3 December 2023). "Sam Bahadur Is A Delight To Watch". Rediff. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Singh 2005, p. 185.

- ^ Sharma, Anil (13 August 2018). "Amritsar's Hindu College common to Manekshaw, ex-PM Manmohan Singh". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Singh 2005, p. 186.

- ^ Chatterjee, Raj (16 November 2005). "Salaam Sam". The Times of India. ISSN 0971-8257. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Singh 2005, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Chhina, Man Aman Singh (17 October 2022). "IMA Dehradun Turns 90: A Dive into History". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Brig. Behram Panthaki (Retd.); Zenobia Panthaki (15 November 2021). "Sam Manekshaw: The Legend Lives on". Seniors Today. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ a b Saighal 2008.

- ^ Tarun, Vijay (30 June 2008). "Saluting Sam Bahadur". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ^ Indian Army (1938). List for October 1938. Government of India. p. 510.

- ^ Indian Army (1939). List for October 1939. Government of India. p. 753.

- ^ a b Indian Army 1945, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Singh 2005, p. 190.

- ^ Thompson, Julian (30 September 2012). Forgotten Voices of Burma: The Second World War's Forgotten Conflict. Random House. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-4481-4874-5.

- ^ "Sam Bahadur: A Soldier's General". The Times of India. 27 June 2008. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ a b c Singh 2005, p. 191.

- ^ "Issue 35532". The London Gazette. 21 April 1942. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ "Recommendation for Award for Manekshaw, Sam Hormuzji Franji Jamshadji". The National Archives (United Kingdom). Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ "Lt. Gen. Manekshaw Takes Over Charge of Eastern Command" (PDF). Press Information Bureau Archive. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ^ Directorate General of Infantry (2000). Infantry, a Glint of the Bayonet. Lancer Publishers. p. 56. ISBN 978-8-1706-2284-0.

- ^ a b Indian Army 1947, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Book University Journal. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. 1975. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Lt. Gen. BNBM Prasad (3 April 2023). "'Soldiers' General': A Tribute to Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw on His Birth Anniversary". News18. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ a b Singh 2005, p. 192.

- ^ New Delhi, Volume 2, Part 1. Ananda Bazar Patrika. p. 77.

- ^ "Jawaharlal, Do You Want Kashmir, Or Do You Want to Give it Away?". Kashmir Sentinel. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ Sengupta, Arjun (1 December 2023). "When Jinnah Asked Sam Manekshaw to Join the Pak Army". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 9 January 2024. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ Chhina, Man Aman Singh (3 March 2024). "Military Digest: Declassified Files Reveal Discussions Over Field Marshals Manekshaw, Cariappa and Their Position in Warrant of Precedence". The Indian Express. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ Singh 2005, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Singh 2005, pp. 193.

- ^ Kumar, Niraj; Driem, George van; Stobdan, Phunchok (18 November 2020). Himalayan Bridge. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-0002-1551-9. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Grover, Verinder; Arora, Ranjana (1999). Events and Documents of Indo-Pak Relations. Deep & Deep Publications. ISBN 978-8-1762-9059-3. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Sinha 1992, p. 131.

- ^ a b "Part I-Section 4: Ministry of Defence (Army Branch)" (PDF). The Gazette of India. 24 March 1956. p. 57. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2022.

- ^ "New Director of Military Training" (PDF). Press Information Bureau Archive. 9 April 1954. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2023.

- ^ "Part I-Section 4: Ministry of Defence (Army Branch)" (PDF). The Gazette of India. 26 February 1955. p. 43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2021.

- ^ Singh 2005, pp. 195–196.

- ^ "Part I-Section 4: Ministry of Defence (Army Branch)" (PDF). The Gazette of India. 15 June 1957. p. 152. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2021.

- ^ Biraia Jaiswal, Pooja (12 December 2021). "Sam Manekshaw Through the Eyes of His Family and Friends". The Week. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "Part I-Section 4: Ministry of Defence (Army Branch)" (PDF). The Gazette of India. 15 February 1958. p. 35. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2020.

- ^ Thapar, Vishal. "Krishna Menon Wanted to Sack Manekshaw". The Sunday Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ a b c Singh 2005, pp. 193–197.

- ^ "Part I-Section 4: Ministry of Defence (Army Branch)" (PDF). The Gazette of India. 19 March 1960. p. 65. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2022.

- ^ "Part I-Section 4: Ministry of Defence (Army Branch)" (PDF). The Gazette of India. 12 December 1959. p. 308. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2022.

- ^ Sinha 1992, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Thakur, Bhartesh Singh (14 January 2016). "Jacob Refused to Depose Against Manekshaw During Inquiry in 1962". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 25 January 2024. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ Jacob, J. F. R. (1997). Surrender at Dacca: Birth of a Nation. Manohar Publishers & Distributors. p. 52. ISBN 978-8-1730-4189-1. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Palit, Maj. Gen. DK (1991). War in The High Himalayas: The Indian Army in Crisis, 1962. Lancer Publishers. pp. 334–335. ISBN 978-8-1706-2138-6.

- ^ Kavic, Lorne J. (28 July 2023). India's Quest for Security: Defence Policies 1947-1965. University of California Press. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-0-5203-3160-0.

- ^ "Part I-Section 4: Ministry of Defence (Army Branch)" (PDF). The Gazette of India. 5 January 1963. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2023.

- ^ Major General Vinay Kumar Singh. "From the Archives (2016) | Sam Manekshaw: The Gentleman Soldier". India Today. Archived from the original on 10 January 2024. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ Singh 2005, p. 199.

- ^ Raghavan, Srinath (4 May 2012). "Soldiers, Statesmen, and India's Security Policy". India Review. 11 (2): 116–133. doi:10.1080/14736489.2012.674829. ISSN 1473-6489. S2CID 154213504.

- ^ Raghavan, Srinath (25 February 2009). "Civil–Military Relations in India: The China Crisis and After". Journal of Strategic Studies. 32 (1): 149–175. doi:10.1080/01402390802407616. ISSN 0140-2390. S2CID 154549258.

- ^ "Part I-Section 4: Ministry of Defence (Army Branch)" (PDF). The Gazette of India. 21 September 1963. p. 321. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Part I-Section 4: Ministry of Defence (Army Branch)" (PDF). The Gazette of India. 11 January 1964. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2021.

- ^ Mukherjee, Anit (1 October 2019). The Absent Dialogue: Politicians, Bureaucrats, and the Military in India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-090592-7.

- ^ Shukla, Ajai (November 2019). "Book review: India's civil-military friction". Broadsword. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Part I-Section 4: Ministry of Defence (Army Branch)" (PDF). The Gazette of India. 19 December 1964. p. 509. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2023.

- ^ Sharma 2007, p. 60.

- ^ Subramaniam, Arjun (9 June 2021). A Military History of India since 1972: Full Spectrum Operations and the Changing Contours of Modern Conflict. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-3198-8.

- ^ Singh, Sushant (13 September 2017). "50 years before Doklam, there was Nathu La: Recalling a very different standoff". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Major General Sheru Thapliyal. "The Nathu La Skirmish: When the Chinese Were Given a Bloody Nose". Centre for Land Warfare Studies. Archived from the original on 2 January 2024. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ Malhotra, Iqbal Chand (1 November 2020). Red Fear: The China Threat. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-9-3898-6759-6.

- ^ Group Captain (Dr) R. Srinivasan (30 April 2023). Peeking at Peking: China, India and the World. HOW Academics. p. 10. ISBN 978-9-3955-2203-8.

- ^ Mitter, Rana (4 September 2020). "The old scars remain: Sino-Indian war of 1967". Telegraph India. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- ^ Singh 2005, p. 201.

- ^ Singh 2005, p. 213.

- ^ "For the Gorkhas – Manekshaw is 'Sam Bahadur'" (PDF). Press Information Bureau Archive. 14 July 1969. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Teotia, Riya (1 December 2023). "Sam Bahadur: When Indira Gandhi Suspected Sam Manekshaw of 'Planning a Military Coup'". WION. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ Singh 2005, p. 203.

- ^ Heitzman, James; Worden, Robert L.; Nyrop, Richard F. (1989). Bangladesh: A Country Study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 30–32. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d The Economist 2008.

- ^ Singh 2005, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Singh 2005, p. 206.

- ^ Singh 2005, p. 207.

- ^ a b c Singh 2005, p. 208.

- ^ "The World: India and Pakistan: Over the Edge". Time. 13 December 1971. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ Mukherjee, Sadhan (1978). India's Economic Relations with USA and USSR: A Comparative Study. Sterling Publishers. p. 157. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ News Review on Science and Technology. Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. 1972. p. 46. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ United States House Committee on the Judiciary (1974). Hearings Before the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, Ninety-third Congress, Second Session, Pursuant to H. Res. 803, a Resolution Authorizing and Directing the Committee on the Judiciary to Investigate Whether Sufficient Grounds Exist for the House of Representatives to Exercise Its Constitutional Power to Impeach Richard M. Nixon, President of the United States of America. May–June 1974. US Government Printing Office. p. 1430. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ a b Singh 2005, p. 209.

- ^ "Documents 302 – 335". Bureau of Public Affairs, United States Department of State. Document 311. Archived from the original on 9 January 2024. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ^ a b Singh 2005, p. 210.

- ^ a b Singh 2005, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Athale, Anil (12 December 2011). "Three Indian Blunders in the 1971 War". Rediff. Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ^ Mehrotra, Puja (17 December 2021). "Sam Manekshaw Was Key Architect of 1971 Win, But it Wasn't His Personal Success: Daughter Maja". ThePrint. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ Zillman, Donald N. (1974). "Prisoners in the Bangladesh War: Humanitarian Concerns and Political Demands". The International Lawyer. 8 (1): 124–135. ISSN 0020-7810. JSTOR 40704858. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ Bass, Gary J. (October 2016). "Bargaining Away Justice: India, Pakistan, and the International Politics of Impunity for the Bangladesh Genocide". International Security. 41 (2): 140–187. doi:10.1162/ISEC_a_00258. ISSN 0162-2889. S2CID 57571115.

- ^ Schendel, Willem van (2020). A History of Bangladesh (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-1084-7369-9.

- ^ Malik, Iftikhar Haider (2008). The History of Pakistan. The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations. Greenwood Press. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-0-3133-4137-3.

- ^ "India-Pakistani Talks Fail to End Kashmir Deadlock". The New York Times. 29 November 1972. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Rangan, Kasturi (8 December 1972). "Accord Reached on Kashmir Line". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ "New India-Pakistan Meeting". The New York Times. 5 December 1972. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ "V K Singh Remembers 'Sam Bahadur', India's First Field Marshal". The New Indian Express. 4 April 2014. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Singh 2005, pp. 214–215.

- ^ "Part I-Section 4: Ministry of Defence (Army Branch)" (PDF). The Gazette of India-Extraordinary. 2 January 1973. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2023.

- ^ Singh 2005, p. 215.

- ^ "Nepal Honours Field Marshal Manekshaw" (PDF). Press Information Bureau Archive. 7 October 1977. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2020.

- ^ Abraham, Rajesh (12 September 2006). "Meet India's Much Sought-after Directors". Rediff Business. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "1965 War-Plan-Seller a DGMO: Gohar Khan". The Times of India. 3 June 2005. Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ "Military Livid at Pak Slur on Sam Bahadur". The Times of India. 8 May 2007. Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ^ Sinha, S. K. "The Making of a Field Marshal". Indian Defence Review. Archived from the original on 2 December 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Gokhale, Nitin (3 April 2014). "Remembering Sam Manekshaw, India's Greatest General, on His Birth Centenary". NDTV. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ^ Major General Vinay Kumar Singh (21 December 2021). "From the Archives: Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw, the Gentleman Soldier". India Today. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ "Tweet by Ved Prakash Malik". X (formerly Twitter). 27 June 2019. Archived from the original on 2 January 2024. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ "Sam Manekshaw Laid to Rest with Full Military Honours". The Times of India. 27 June 2008. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ Thapar, Karan (5 July 2008). "Unbelievable or Deliberate?". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 18 January 2024. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Pandit, Rajat (28 June 2008). "Lone Minister Represents Govt at Manekshaw's Funeral". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ "NRIs Irked by Poor Manekshaw Farewell". DNA India: Daily News & Analysis. 7 July 2008. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ^ "No National Mourning for Manekshaw". The Indian Express. 29 June 2008. Archived from the original on 25 January 2024. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Singh 2005, p. 189.

- ^ "With His Charm, Manekshaw Won Hearts More Than Wars". The Times of India. 28 June 2008. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ Hasnain (Retd), Lieutenant General Syed Ata (3 December 2023). "'Don't call me Uncle. Call me Sam'". Rediff. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Batliwala, Brandy (27 June 2018). "Missing Sam". The Indian Express. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ Thottam, Jyoti (3 July 2008). "Sam Manekshaw". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ Bajwa, Mandeep Singh (25 May 2014). "Sam Manekshaw's Leadership Style". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ Mishra, Achyut (27 June 2019). "Sam Manekshaw, the General Who Told Indira When Indian Army Wasn't Ready for a War". ThePrint. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ Bedi, Rahul (13 September 2022). "Why the Narrative on Manekshaw – India's Uncrowned CDS – is Captivating Military Veterans Now". The Wire. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ Prasannan, R. "How Sam Manekshaw crafted a 'perfect war'". The Week. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Stamp on Manekshaw Released". The Hindu. 18 December 2008. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ^ "Army Complex to be Named After Manekshaw". The Economic Times. 30 June 2008. ISSN 0013-0389. Archived from the original on 6 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ "President's Address at the Inauguration of the Manekshaw Centre". President of India. 21 October 2010. Archived from the original on 25 January 2024. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ "Army Commander's Conference Begins". Press Information Bureau Archive. Archived from the original on 17 April 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ "Bengaluru: Republic Day Celebrations Amidst High Security and Safety Measures". The Hindu. 24 January 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ "Modi's Choice: Flyover in Ahmedabad to be Named After Sam Manekshaw". Desh Gujarat. 11 September 2008. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ Thiagarajan, Shanta (3 April 2014). "Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw Statue Unveiled on Ooty–Coonoor Road". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ "Manekshaw Bridge Thrown Open to Traffic". The Hindu. 10 March 2009. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ "Manekshaw Papers". Centre for Land Warfare Studies. Archived from the original on 2 January 2024. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ Bray, Catherine (1 December 2023). "Sam Bahadur Review – Indian War Hero Sam Manekshaw is the Guy Who Can Do No Wrong". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ Kortenaar, Neil ten (2004). Self, Nation, Text in Salman Rushdie's "Midnight's Children". McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-0-7735-2615-0.

- ^ Singh, Maj Gen Sukhwant (1981). India's Wars Since Independence: The Liberation of Bangladesh. Lancer Publishers. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-9355-0160-2. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Cloughley, Brian (5 January 2016). A History of the Pakistan Army: Wars and Insurrections. Simon & Schuster. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-1-6314-4039-7.

- ^ Indian Defence Review. Lancer International. 2004. p. 5.

- ^ Citino, Robert M. (25 May 2022). Blitzkrieg to Desert Storm: The Evolution of Operational Warfare. University Press of Kansas. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-7006-3401-9.

- ^ Rajagopalan, Swarna (21 March 2014). Security and South Asia: Ideas, Institutions and Initiatives. Routledge. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-1-3178-0948-7.

- ^ Bakshi, Major General GD (1 January 1988). Indian Defence Review Jan-Jun 1988 (Vol 3.1). Lancer Publishers. p. 76. ISBN 978-8-1706-2342-7. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Husain, Ross Masood (1989). "Indian Combat Doctrine: Some Pertinent Aspects". Strategic Studies. 12 (4). Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad: 93–98. ISSN 1029-0990. JSTOR 45182535. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Citino, Robert M. (May 2012). "India's Blitzkrieg". Military History. 29 (1): 60–67.

- ^ Report – Government of India, Ministry of Defence. Ministry of Defence (India). 1972. p. 167. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Ṣiddīqī, ʻAbdurraḥmān (2004). East Pakistan the End Game: An Onlooker's Journal 1969–1971. Oxford University Press. pp. 48, 206. ISBN 978-0-1957-9993-4. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Dutta, Sujan (19 September 2021). "Remembering the Exploits of BSF's Assistant Commandant Ram Krishna Wadhwa and Lance Naik Nar Bahadur Chhetri". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 17 January 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Chari, PR. "Sam Manekshaw in the 1971 War" (PDF). Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies: 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 January 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Singh, Major General Sukhwant (1981). Defence of the Western Border Volume Two. Vikas Publishing House. pp. 178–180. ISBN 0-7069-1277-2.

- ^ Noorani, A. G. (27 February 2003). "Our Secrets in British Archives". Frontline. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ "Frankly Speaking". Frontline. 12 August 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ Major General Partap Narain (1994). Indian Arms Bazaar. Shipra Publications. pp. V–VII. ISBN 978-8-1854-0235-2. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Singh, Jogindar (1993). Behind the Scenes: An Analysis of India's Military Operations, 1947–1971. Lancer Publishers. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-8978-2920-2. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Barua, Pradeep (1 January 2005). The State at War in South Asia. University of Nebraska Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-8032-1344-9. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Nair, Pavan (2009). "An Evaluation of India's Defence Expenditure". Economic and Political Weekly. 44 (51): 40–46. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 25663913. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ Lt. Gen. Vinod Bhatia (2021). "Planning and Impact of Special Operations During the 1971 Indo-Pakistan War" (PDF). Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. ISSN 0976-1004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 May 2022. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ Jackson, Robert; International Institute for Strategic Studies (17 June 1978). South Asian Crisis: India—Pakistan—Bangla Desh. Chatto & Windus. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-3490-4163-3. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Conboy, Kenneth (20 May 2012). Elite Forces of India and Pakistan. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-7809-6825-4. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ Schendel, Willem Van (20 October 2015). "A War Within a War: Mizo Rebels and the Bangladesh Liberation Struggle". Modern Asian Studies. 50 (1): 75–117. doi:10.1017/S0026749X15000104. ISSN 0026-749X. S2CID 146614327.

- ^ Nag, Sajal (2012). "A Gigantic Panopticon: Counter-Insurgency and Modes of Disciplining and Punishment in Northeast India" (PDF). Logistics and Governance: Fourth Critical Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2024.

Bibliography

Books

- List for October 1945 (Part I). Indian Army, Government of India. 1945.

- List Special Edition for August 1947. Indian Army, Government of India. 1947.

- Sharma, Satinder (2007). Services Chiefs of India. Northern Book Centre. ISBN 978-8-1721-1162-5.

- Singh, Vijay Kumar (2005). Leadership in the Indian Army: Biographies of Twelve Soldiers. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-0-7619-3322-9.

- Sinha, Srinivas Kumar (1992). A Soldier Recalls. Lancer Publishers. ISBN 978-8-1706-2161-4.

News articles

- "Obituary: Sam Manekshaw". The Economist. No. 5 (July 2008). 3 July 2008. p. 107. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2008.

- Mehta, Ashok K. (27 January 2003). "Play It Again, Sam: A Tribute to the Man Whose Wit Was as Astounding as His Military Skill". Outlook. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- Pandya, Haresh (30 June 2008). "Sam H.F.J. Manekshaw Dies at 94; Key to India's Victory in 1971 War". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 12 December 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Saighal, Vinod (30 June 2008). "Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw". [The Guardian]]. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

External links

- Sam Manekshaw at the Indian Army's website

- Lecture and Q&A by Sam Manekshaw at the DSSC, hosted by the Indian Defence Review