NK1 receptor antagonist

Neurokinin 1 (NK1) antagonists (-pitants) are a novel class of medications that possesses unique antidepressant,[1][2] anxiolytic,[3] and antiemetic properties. NK-1 antagonists boost the efficacy of 5-HT3 antagonists to prevent nausea and vomiting. The discovery of neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptor antagonists was a turning point in the prevention of nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy.[4]

An example of a drug in this class is aprepitant. Chemotherapy-induced emesis appears to consist of acute and delayed phases. So far, the acute phase emesis responds to 5-HT3 antagonists while the delayed phase remains difficult to control. The discovery and development of NK1 receptor antagonists have elicited antiemetic effect in both acute and especially in delayed phases of emesis.[5] Casopitant, netupitant and rolapitant are some newer additions in this group. Rolapitant has a significantly longer half-life of 160 hours and was approved by the US FDA in 2015.

The first registered clinical use of NK1 receptor antagonists was the treatment of emesis, associated with cancer chemotherapy.[6]

History

In 1931, von Euler and Gaddum discovered substance P (SP) in horse brain and intestine. The substance showed strong vasodilatory effects and contractile activity on the rabbit gut. A great effort was put into purifying this substance from diverse mammalian tissue, but 30 years of research were without success. Nonmammalian peptides that elicited the same vasodilatory and contractile effects as SP were discovered by Erspamer in the early 1960s. These peptides had a common C-terminal sequence, and were grouped together as tachykinins. In 1971, Chang managed to purify SP from horse intestine and identify its amino acid sequence; SP was then classified as a mammalian tachykinin. Later it became clear that SP was a neuropeptide that was common in the central and peripheral nervous system. In the mid 1980s, the additional mammalian tachykinin neurokinin A (NKA) and neurokinin B (NKB) were discovered.[7][8] This led to further research, resulting in the isolation of the genes that encoded the mammalian tachykinins and eventually the discovery of three different tachykinin receptors. In 1984, it was decided that the tachykinin receptors should be called tachykinin NK1 receptor, tachykinin NK2 receptor and tachykinin NK3 receptor.[7][9]

Biological research that identified the many functions of tachykinins sparked interest in neurokinin receptor antagonists development.[8] In the 1980s, several peptide antagonists derived from SP were the first NK1 receptor antagonists. However, these compounds, like most peptide compounds, had problems with selectivity, potency, solubility and bioavailability. For this reason, pharmaceutical companies concentrated on developing non-peptide NK1 receptor antagonists, and in 1991, three different companies revealed their first results. Since then, non-peptide NK1 receptor antagonists have been researched extensively and many structures and patents have appeared. Proposing the concept in the early 1990s, in 1998 Kramer, et al., reported clinical data on the efficacy and safety of MK-869 (aprepitant) in patients with major depressive disorder.[1] In 2003, the first NK1 receptor antagonist, aprepitant (Emend), received marketing approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[10][11][12]

The neurokinin-1 receptor

Tachykinins are a family of neuropeptides that share the same hydrophobic C-terminal region with the amino acid sequence Phe-X-Gly-Leu-Met-NH2, where X represents a hydrophobic residue that is either an aromatic or a beta-branched aliphatic. The N-terminal region varies between different tachykinins.[13][14][15] The term tachykinin originates in the rapid onset of action caused by the peptides in smooth muscles.[15] SP is the most researched and potent member of the tachykinin family. It is an undecapeptide with the amino acid sequence Arg-Pro-Lys-Pro-Gln-Gln-Phe-Phe-Gly-Leu-Met-NH2.[13] SP binds to all three of the tachykinin receptors, but it binds most strongly to the NK1 receptor.[14]

Tachykinin NK1 receptor, often referred to as NK1 receptor, is a member of family 1 (rhodopsin-like) of G protein-coupled receptors and binds to the Gαq protein.[8] NK1 receptor consists of 407 amino acid residues, and it has a molecular weight of 58.000.[13][16] NK1 receptor, as well as the other tachykinin receptors, is made of seven hydrophobic transmembrane (TM) domains with three extracellular and three intracellular loops, an amino-terminus and a cytoplasmic carboxy-terminus. The loops have functional sites, including two cysteines amino acids for a disulfide bridge, Asp-Arg-Tyr, which is responsible for association with arrestin and, Lys/Arg-Lys/Arg-X-X-Lys/Arg, which interacts with G-proteins.[8][16]

Drug discovery and development

In 1991, three different groups researched different NK1 receptor antagonists by screening of chemical collections. Eastman Kodak and Sterling Winthrop discovered steroid series of tachykinin NK1 receptor antagonists that yielded some compounds but lacked sufficient affinity for the NK1 receptor, despite structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies that were performed. This series proved to have significant toxicity. Even though many derivatives of the steroid compounds have been synthesized, biological activity has not been improved.[12][17]

Rhône-Poulenc discovered the compound RP-67580, which has high affinity for the NK1 receptor in rats and mice, but not in humans. SAR studies that were performed in order to improve the selectivity for the human NK1 receptor resulted in the development of a compound called RPR-100893. This compound showed good activity in vivo and in models of pain and was developed up to phase II for the treatment of migraines but then terminated, as was the case with other NK1 receptor antagonists that were tested for the same indication.[12][17]

The third company, Pfizer, discovered a benzylamino quinuclidine structure, which was called CP-96345 (figure 1). CP-96345 has a rather simple structure, composed of a rigid quinuclidine scaffold containing a basic nitrogen atom, a benzhydril moiety and an o-methoxy-benzylamine group. This compound showed high affinity for the NK1 receptor, but it also interacted with Ca2+ binding sites. Strongly basic quinuclidine nitrogen on the compound was considered to be responsible for this Ca2+ binding, which caused a number of systemic effects, unrelated to the blocking of the NK1 receptor. For that reason and also to simplify the structure, alkylation at this site was performed to produce analogs.

The compound CP-99994 was synthesized by replacing the quinuclidine ring with a piperidine ring and benzhydryl moiety by a benzyl group (figure 2).[12][17] CP-99994 had a high affinity for the human NK1 receptor and it started a great number of structure–activity studies, each intending to identify the structural requirements for high-affinity interaction with the NK1 receptor, and to make the molecule even simpler and improve its chemico-physical and pharmacological properties.[17] CP-99994 eased dental pain in humans and entered phase II clinical trials; these were discontinued because of poor bioavailability. Pfizer researched several other related NK1 receptor antagonists. CJ-11974, also called ezlopitant, was a close analog of CP-96345 that had an isopropyl group on the methoxybenzyl ring. It was developed up to phase II clinical trials for chemotherapy-induced emesis before development was discontinued. CP-122721 was a CP-99994 analog that had a trifluoromethoxy group in the o-methoxybenzyl ring. It entered phase II trials for the treatment of depression, emesis and inflammatory diseases, but no further development has been reported.[12]

Development of the first drug

In 1993, Merck started performing SAR studies of NK1 receptor antagonists, based on both CP-96345 and CP-99994. L-733,060 is one of the compounds that were developed from CP-99994. It has a 3,5-bistrifluoromethyl benzylether piperidine in place of 2-methoxy benzylamine moiety of CP-99994 compound. To improve oral bioavailability, the piperidine nitrogen was functionalized in order to reduce its basic nature. The group that gave the best effects on basicity was 3-oxo-1,2,4-triazol-5-yl moiety and it gave compounds such as L-741671 and L-742694. A morpholine nucleus that was introduced in L-742694 was found to enhance NK1 binding affinity.[11] This nucleus was preserved in further modifications. In order to prevent possible metabolic deactivation, several refinements such as methylation on the C alfa of the benzyl ring and fluorination on the phenyl ring were introduced. These changes produced the compound MK-869, which showed high affinity for the NK1 receptor and high oral activity (figure 3). MK-869 is also called aprepitant, and was studied in pain, migraines, emesis and psychiatric disorders. These studies led to the FDA-approved drug Emend for chemo therapy-induced nausea and vomiting, and is available for oral use.[12] A water-soluble phosphoryl prodrug for intravenous use, called fosaprepitant, is also available and is marketed as Ivemend.[18] Aprepitant was also believed to be effective in the treatment of depression. It entered phase III trials before the development for this indication was discontinued.[12]

Other compounds

Many compounds have been described by various pharmaceutical companies besides the compounds that led to the discovery of aprepitant. GR-205171 (figure 4) was developed by Glaxo and was based on CP-99994. GR-205171 had a tetrazole ring in position 4 of the benzyl ring of CP-99994 that was intended to increase oral bioavailability and improve pharmacokinetic properties. It was developed up to phase II clinical trials for the treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting, migraine and motion sickness. It showed good results in emesis, but development was discontinued.[12]

LY-303870, or lanepitant (figure 5), is an N-acetylated reduced amide of L-tryptophan that was discovered by Eli Lilly. It underwent phase IIa clinical trials for the treatment of osteoarthritis pain but showed no significant effects. Eli Lilly made some SAR work on its structure and developed some compounds that did not enter clinical trials.[12]

By a general hypothesis on peptideric G protein-coupled receptors binding site, Takeda discovered a series of N-benzylcarboxyamides in 1995. One of those compounds, TAK-637 (figure 6), underwent phase II clinical trials for urinary incontinence, depression and irritable bowel syndrome, but the development was discontinued. There are still other compounds that have been researched in the past and even reached clinical trials, and research continues despite the lack of success in clinical trials.[11][12]

Binding

There is more than one ligand binding domain on the NK1 receptor for the non-peptide antagonists, and these binding domains can be found in various places. The main ligand binding site is in the hydrophobic core between the loops and the outer segments of transmembrane domains 3–7 (TM3–TM7).[16] Several residues, such as Gln165 (TM4), His197 (TM5), His265 (TM6) and Tyr287 (TM7) are involved in the binding of many non-peptide antagonists of the NK1 receptors.[7][16] It has been stated that Ala-replacement of His197 decreases the binding affinity of CP-96345 for the NK1 receptor. His197 interacts with the benzhydryl moiety of CP-96345. Experiments have showed that replacing Val116 (TM3) and Ile290 (TM7) decreases the binding affinity of CP-96345. Evidence indicates that these residues probably do not interact with antagonists, but would rather indirectly influence the overall conformation of the antagonist binding site. The residue Gln165 (TM4) has also proven to be meaningful for the binding of several non-peptide antagonists, possibly through the formation of a hydrogen bond.[17][19] Phe268 and Tyr287 have been proposed as possible contact points for both agonist and antagonist binding domains.[16]

The significance of His265 has been confirmed in the binding of antagonists to NK1 receptor. His265 interacts favorably with the 3,5-bis-trifluoromethylphenyl group (TFMP group) of an analog CP-96345. Nonetheless, it has been demonstrated that Ala-replacement of His265 does not affect the binding affinity of CP-96345.[11]

Some other residues that are thought to be involved in the binding of non-peptide antagonists to NK1 receptor are Ser169, Glu193, Lys194, Phe264, Phe267, Pro271 and Tyr272. Each structural class of non-peptide NK1 receptor antagonists appears to interact with a specific set of residues within the common binding pocket.[7][16]

Structure-activity relationship (SAR) and pharmacophore

There are at least three essential elements which are important for the interactivity of a ligand with the NK1 receptor. First, the ion-pair site interactivity with the bridgehead nitrogen; second, the accessory binding site interactivity with the benzhydryl group; and third, the specific site interactivity with the (2-methoxybenzyl) amino side chain. Studies have shown that compounds with piperidine ring have selectivity for NK1 receptor over NK2, NK3, opioid and 5-HT receptors. By adding an N-heteroaryl-2-phenyl-3-(benzyloxy) group to the piperidine, a selective NK1 receptor antagonist is produced. Studies have also shown that the dihedral angle between groups on C-2 and C-3 in CP-99994 is critical for activity of the NK1 receptor antagonists.[15] The bridgehead basic nitrogen is thought to interact with the NK1 receptor by mediating its recognition through ion pair site.[20] It has been found that the basic nitrogen atoms in pyrido[3,4-b]pyridine do have an anchoring function in the phospholipid component of the cell membrane.[15]

In the development of MK-869, it was discovered that 3,5-disubstitution of the benzyl ring in the ether series gave greater potency than the 2-methoxy substitution in earlier benzylamine structures. It also was revealed that the TFMP group appeared to be especially important, and it is believed that it enhances activity in vivo and improves metabolism. Other groups, like the ortho-methoxyphenyl group, can be important in specific cases, but are thought to play a greater role in ligand preorganization through intramolecular hydrogen bonding, rather than through direct interaction with binding site residue.[11] The presence of an intramolecular face-to-face π–π interaction between two aromatic rings is a common feature of high affinity NK1 receptor antagonists. This feature is thought to be important in stabilizing the bioactive conformation. This interaction can be increased with a conformationally-restricted system, such as an eight-membered ring introduced into the naphthyridine ring.[20]

Future development

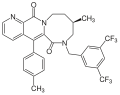

Chemotherapy-induced emesis is a major problem in cancer treatment. A new compound, T-2328 (figure 7), a non-peptide antagonist of the tachykinin NK1 family, is studied for that purpose. T-2328 is administered intravenously, and treats both acute and delayed emesis. It is proposed to exert its anti-emetic effect through acting on brain NK1 receptors. T-2328 is very potent; the inhibition constant is of subnanomolar range and is 16 times lower than that of aprepitant. The inhibition is highly selective for NK1 receptors.

The NK2 and NK3 receptors are also targets for novel classes of medications, and also show prominent antidepressive and anxiolytic effects.[21] Studies showed that the inhibition constant (Ki) for NK2 receptors was >10000-fold higher and for NK3 receptors >1000-fold higher than that for NK1 receptors. The affinity was also much lower for NK2 and NK3 receptors.[5] Since tachykinins were discovered, they have been shown to possess biological activity in number of pathological and physiological systems. Nevertheless, the therapeutic potential of the tachykinin antagonists has not been fully understood.[6]

See also

- Aprepitant

- Casopitant

- Fosaprepitant

- Maropitant

- Rolapitant

- Tachykinin receptor

- G protein-coupled receptors

References

- ^ a b Kramer MS, Cutler N, Feighner J, Shrivastava R, Carman J, Sramek JJ, et al. (September 1998). "Distinct mechanism for antidepressant activity by blockade of central substance P receptors". Science. 281 (5383): 1640–5. Bibcode:1998Sci...281.1640K. doi:10.1126/science.281.5383.1640. PMID 9733503.

- ^ Varty GB, Cohen-Williams ME, Hunter JC (February 2003). "The antidepressant-like effects of neurokinin NK1 receptor antagonists in a gerbil tail suspension test". Behav Pharmacol. 14 (1): 87–95. doi:10.1097/00008877-200302000-00009. PMID 12576885. S2CID 12218489.

- ^ Varty GB, Cohen-Williams ME, Morgan CA, et al. (2002), "The gerbil elevated plus-maze II: anxiolytic-like effects of selective neurokinin NK1 receptor antagonists", Neuropsychopharmacology, 27 (3): 371–9, doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00313-5, PMID 12225694.

- ^ Hesketh, P. J. (1994), "New treatment options for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting", Supportive Care in Cancer, 12 (8): 550–554, doi:10.1007/s00520-004-0651-0, PMID 15232725, S2CID 6081469, archived from the original on 2013-01-29

- ^ a b Watanabe, Y.; Asai, H.; Ishii, T.; Kiuchi, S.; Okamoto, M.; Taniguchi, H.; Nagasaki, M.; Saito, A. (January 2008), "Pharmacological characterization of T-2328, 2-fluoro-4 '-methoxy-3 '-((((2S,3S)-2-phenyl-3-piperidinyl)amino)methyll)(1,1 '-biphenyl)-4-carbonitrile dihydrochloride, as a brain-penetrating antagonist of tachykinin NK1 receptor", Journal of Pharmacological Sciences, 106 (1): 121–127, doi:10.1254/jphs.FP0071400, PMID 18187929

- ^ a b Brain, S. D.; Cox, H. M. (2006), "Neuropeptides and their receptors: innovative science providing novel therapeutic targets", British Journal of Pharmacology, 147 (S1): S202–S211, doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706461, PMC 1760747, PMID 16402106

- ^ a b c d Maggi, C. A. (September 1994), "Mammalian Tachykinin Receptors", General Pharmacology, 26 (5): 911–944, doi:10.1016/0306-3623(94)00292-U, PMID 7557266

- ^ a b c d Satake, H.; Kawada, T. (August 2006), "Overview of the primary structure, tissue-distribution, and functions of tachykinins and their receptors", Current Drug Targets, 7 (8): 963–974, doi:10.2174/138945006778019273, PMID 16918325

- ^ Saria, A. (June 1999), "The Tachykinin NK1 receptor in the brain: pharmacology and putative functions", European Journal of Pharmacology, 375 (1–3): 51–60, doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(99)00259-9, PMID 10443564

- ^ Hoffman, T.; Bös, M.; Stadler, H.; Schnider, P.; Hunkeler, W.; Godel, T.; Galley, G.; Ballard, T. M.; et al. (March 2006), "Design and synthesis of a novel, achiral class of highly potent and selective, orally active neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists", Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 16 (5): 1362–5, doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.11.047, PMID 16332435

- ^ a b c d e Humphrey, J. M. (2003), "Medicinal Chemistry of Selective Neurokinin-1 Antagonists", Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry, 3 (12): 1423–1435, doi:10.2174/1568026033451925, PMID 12871173

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Quartara, L.; Altamura, M. (August 2006), "Tachykinin receptors antagonists: From research to clinic", Current Drug Targets, 7 (8): 975–992, doi:10.2174/138945006778019381, PMID 16918326

- ^ a b c Ho, W. Z.; Douglas, S. D. (December 2004), "Substance P and neurokinin-1 receptor modulation of HIV", Journal of Neuroimmunology, 157 (1–2): 48–55, doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.022, PMID 15579279, S2CID 14975995

- ^ a b Page, N. M. (August 2005), "New challenges in the study of the mammalian Tachykinins", Peptides, 26 (8): 1356–1368, doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.030, PMID 16042976, S2CID 23094292

- ^ a b c d Datar, P.; Srivastava, S.; Coutinho, E.; Govil, G. (2004), "Substance P: Structure, Function, and Therapeutics", Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry, 4 (1): 75–103, doi:10.2174/1568026043451636, PMID 14754378

- ^ a b c d e f Almeida, T. A.; Rojo, J.; Nieto, P. M.; Hernandez, FM; Martin, J. D.; Candenas, M. L.; Candenas, ML (August 2004), "Tachykinins and Tachykinins Receptors: Structure and Activity Relationships", Current Medicinal Chemistry, 11 (15): 2045–2081, doi:10.2174/0929867043364748 (inactive 1 November 2024), PMID 15279567

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ a b c d e Quartara, L.; Maggi, C. A. (December 1997), "The tachykinin NK1 receptor. Part I: Ligands and mechanisms of cellular activation", Neuropeptides, 31 (6): 537–563, doi:10.1016/S0143-4179(97)90001-9, PMID 9574822, S2CID 13735836

- ^ Pennefather, J. N.; Lecci, A.; Candenas, M. L.; Patak, E.; Pinto, F. M.; Maggi, C. A. (2004), "Tachykinins and tachykinin receptors: a growing family", Life Sciences, 74 (12): 1445–1463, doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.039, PMID 14729395

- ^ a b Seto, S.; Tanioka, A.; Ikeda, M.; Izawa, S. (March 2005), "Design and synthesis of novel 9-substituted-7-aryl-3,4,5,6-tetrahydro-2H-pyrido(4,3-b)- and (2,3-b)-1,5-oxazocin-6-ones as NK1 antagonists", Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 15 (5): 1479–1484, doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.12.091, PMID 15713411

- ^ Salomé N, Stemmelin J, Cohen C, Griebel G (April 2006). "Selective blockade of NK2 or NK3 receptors produces anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like effects in gerbils". Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 83 (4): 533–9. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2006.03.013. PMID 16624395. S2CID 15134994.