LZ 129 Hindenburg

| LZ 129 Hindenburg | |

|---|---|

Hindenburg at NAS Lakehurst | |

| General information | |

| Type | Hindenburg-class airship |

| Manufacturer | Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH |

| Owners | Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei |

| Registration | D-LZ129 |

| Radio code | DEKKA[1] |

| Flights | 63[2] |

| History | |

| Manufactured | 1931–1936 |

| First flight | March 4, 1936 |

| In service | 1936–1937 |

| Last flight | May 6, 1937 |

| Fate | Destroyed in fire and crash |

LZ 129 Hindenburg (Luftschiff Zeppelin #129; Registration: D-LZ 129) was a German commercial passenger-carrying rigid airship, the lead ship of its class, the longest class of flying machine and the largest airship by envelope volume.[3] It was designed and built by the Zeppelin Company (Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH) on the shores of Lake Constance in Friedrichshafen, Germany, and was operated by the German Zeppelin Airline Company (Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei). It was named after Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, who was President of Germany from 1925 until his death in 1934.

The airship flew from March 1936 until it was destroyed by fire 14 months later on May 6, 1937, while attempting to land at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in Manchester Township, New Jersey, at the end of the first North American transatlantic journey of its second season of service. This was the last of the great airship disasters; it was preceded by the crashes of the British R38, the US airship Roma, the French Dixmude, the USS Shenandoah, the British R101, and the USS Akron.

Design and development

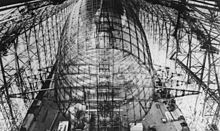

The Zeppelin Company had proposed LZ 128 in 1929, after the world flight of the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin. This ship was to be approximately 245 m (804 ft) long and carry 140,000 cubic metres (4,900,000 cu ft) of hydrogen. Ten Maybach engines were to power five tandem engine cars (a plan from 1930 showed only four). The disaster of the British airship R 101 prompted the Zeppelin Company to reconsider the use of hydrogen, therefore scrapping the LZ 128 in favour of a new airship designed for helium, the LZ 129. Initial plans projected the LZ 129 to have a length of 248 metres (814 ft), but 11 m (36 ft) was dropped from the tail in order to allow the ship to fit in Lakehurst Hangar No. 1.[4]

Manufacturing of components began in 1931, but construction of the Hindenburg did not commence until March 1932. The delay was largely due to Daimler-Benz designing and refining the LOF-6 diesel engines to reduce weight while fulfilling the output requirements set by the Zeppelin Company.[4]

Hindenburg had a duralumin structure, incorporating 15 Ferris wheel-like main ring bulkheads along its length, with 16 cotton gas bags fitted between them. The bulkheads were braced to each other by longitudinal girders placed around their circumferences. The airship's outer skin was of cotton doped with a mixture of reflective materials intended to protect the gas bags within from radiation, both ultraviolet (which would damage them) and infrared (which might cause them to overheat). The gas cells were made by a new method pioneered by Goodyear using multiple layers of gelatinized latex rather than the previous goldbeater's skins. In 1931 the Zeppelin Company purchased 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) of duralumin salvaged from the wreckage of the October 1930 crash of the British airship R101.[5]

Hindenburg's interior furnishings were designed by Fritz August Breuhaus, whose design experience included Pullman coaches, ocean liners, and warships of the German Navy.[6] The upper "A" Deck contained 25 small two-passenger cabins in the middle flanked by large public rooms: a dining room to port and a lounge and writing room to starboard. Paintings on the dining room walls portrayed the Graf Zeppelin's trips to South America. A stylized world map covered the wall of the lounge. Long slanted windows ran the length of both decks. The passengers were expected to spend most of their time in the public areas, rather than their cramped cabins.[7]

The lower "B" Deck contained washrooms, a mess hall for the crew, and a smoking lounge. Harold G. Dick, an American representative from the Goodyear Zeppelin Company,[8] recalled "The only entrance to the smoking room, which was pressurized to prevent the admission of any leaking hydrogen, was via the bar, which had a swiveling air lock door, and all departing passengers were scrutinized by the bar steward to make sure they were not carrying out a lit cigarette or pipe."[9][10]

Use of hydrogen instead of helium

Helium was initially selected for the lifting gas because it was the safest to use in airships, as it is not flammable.[11] One proposed measure to save helium was to make double-gas cells for 14 of the 16 gas cells; an inner hydrogen cell would be protected by an outer cell filled with helium,[11][12] with vertical ducting to the dorsal area of the envelope to permit separate filling and venting of the inner hydrogen cells. At the time, however, helium was also relatively rare and extremely expensive as the gas was available in industrial quantities only from distillation plants at certain oil fields in the United States. Hydrogen, by comparison, could be cheaply produced by any industrialized nation and being lighter than helium also provided more lift. Because of its expense and rarity, American rigid airships using helium were forced to conserve the gas at all costs and this hampered their operation.[13]

Despite a U.S. ban on the export of helium under the Helium Control Act of 1927,[14] the Germans designed the airship to use the far safer gas in the belief that they could convince the U.S. government to license its export. When the designers learned that the National Munitions Control Board refused to lift the export ban, they were forced to re-engineer Hindenburg to use flammable hydrogen gas, which was the only alternative lighter-than-air gas that could provide sufficient lift.[11] One of the side benefits of being forced to utilize the flammable yet lighter hydrogen was that more passenger cabins could be added.

Operational history

Launching and trial flights

Four years after construction began in 1932, Hindenburg made its maiden test flight from the Zeppelin dockyards at Friedrichshafen on March 4, 1936, with 87 passengers and crew aboard. These included the Zeppelin Company chairman, Dr. Hugo Eckener, as commander, former World War I Zeppelin commander Lt. Col. Joachim Breithaupt representing the German Air Ministry, the Zeppelin Company's eight airship captains, 47 other crew members, and 30 dockyard employees who flew as passengers.[15] Harold G. Dick was the only non-Luftschiffbau representative aboard. Although the name Hindenburg had been quietly selected by Eckener over a year earlier,[16] only the airship's formal registration number (D-LZ129) and the five Olympic rings (promoting the 1936 Summer Olympics to be held in Berlin that August) were displayed on the hull during its trial flights. As the airship passed over Munich on its second trial flight the next afternoon, the city's Lord Mayor, Karl Fiehler, asked Eckener by radio the LZ129's name, to which he replied "Hindenburg". On March 23, Hindenburg made its first passenger and mail flight, carrying 80 reporters from Friedrichshafen to Löwenthal. The ship flew over Lake Constance with Graf Zeppelin.[17]

The name Hindenburg lettered in 1.8-metre (5 ft 11 in) high red Fraktur script (designed by Berlin advertiser Georg Wagner) was added to its hull three weeks later before the Deutschlandfahrt on March 26. No formal naming ceremony for the airship was ever held.[18]

The airship was operated commercially by the Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei (DZR) GmbH, which had been established by Hermann Göring in March 1935 to increase Nazi influence over airship operations.[19] The DZR was jointly owned by the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin (the airship's builder), the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (German Air Ministry), and Deutsche Lufthansa A.G. (Germany's national airline at that time), and also operated the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin during its last two years of commercial service to South America from 1935 to 1937. Hindenburg and its sister ship, the LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II (launched in September 1938), were the only two airships ever purpose-built for regular commercial transatlantic passenger operations, although the latter never entered passenger service before being scrapped in 1940.

After a total of six flights made over a three-week period from the Zeppelin dockyards where the airship had been built, Hindenburg was drafted — over Hugo Eckener's objections — for a formal public debut in a 6,600 km (4,100 mi) Nazi Party propaganda flight around Germany (Die Deutschlandfahrt) made jointly with the Graf Zeppelin from March 26 to 29.[20] This was to be followed by its first commercial passenger flight, a four-day transatlantic voyage to Rio de Janeiro that departed from the Friedrichshafen Airport in nearby Löwenthal on March 31.[21] After again departing from Löwenthal on 6 May on its first of ten round trips to North America made in 1936,[22] all Hindenburg's subsequent transatlantic flights to both North and South America originated at the airport at Frankfurt am Main.[23][24]

Die Deutschlandfahrt

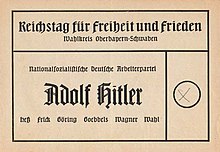

Although designed and built for commercial transatlantic passenger, air freight, and mail service, at the behest of the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda (Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda or Propagandaministerium), Hindenburg was first pressed into use by the Air Ministry (its DLZ co-operator) as a vehicle for the delivery of Nazi propaganda.[25] On March 7, 1936, ground forces of the German Reich had entered and occupied the Rhineland, a region bordering France, which had been designated in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles as a de-militarized zone established to provide a buffer between Germany and that neighboring country.

In order to justify its remilitarization—which was also a violation of the 1925 Locarno Pact[26]—a post hoc referendum was quickly called by Hitler for March 29 to "ask the German people" to both ratify the Rhineland's occupation by the German Army, and to approve a single party list composed exclusively of Nazi candidates to sit in the new Reichstag. The Hindenburg and the Graf Zeppelin were designated by the government as a key part of the process.[27] As a public relations ploy, Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels demanded that the Zeppelin Company make the two airships available for a tour of Germany (Deutschlandfahrt), flying "in tandem" around Germany over the four-day period prior to the voting with a joint departure from Löwenthal on the morning of March 26.[28]

The Zeppelin Company chairman, Dr. Hugo Eckener, disapproved of this propaganda use of his craft. According to American reporter William L. Shirer, "Hugo Eckener, who is getting [the Hindenburg] ready for its maiden flight to Brazil, strenuously objected to putting it in the air this weekend on the ground it was not fully tested, but Dr. Goebbels insisted. Eckener, no friend of the regime, refused to take it up himself, but allowed Captain [Ernst] Lehmann to. [Goebbels] is reported howling mad and is determined to get Eckener."[29]

While gusty wind conditions on the morning March 26 threatened a safe launch of the new airship, Hindenburg's commander, Captain Ernst Lehmann, was determined to impress the politicians, Nazi party officials, and press present at the airfield with an "on time" departure and thus proceeded with its launch despite the adverse conditions. As the massive airship began to rise under full engine power she was caught by a 35-degree crosswind gust, causing her lower vertical tail fin to strike and be dragged across the ground, resulting in significant damage to the bottom portion of the airfoil and its attached rudder.[30][31] Hugo Eckener was furious and rebuked Lehmann.[32]

Graf Zeppelin, which had been hovering above the airfield waiting for Hindenburg to join it, had to start off on the propaganda mission alone while LZ 129 returned to her hangar. There temporary repairs were quickly made to its empennage before joining up with the smaller airship several hours later.[33] As millions of Germans watched from below, the two giants of the sky sailed over Germany for the next four days and three nights, dropping propaganda leaflets, blaring martial music and slogans from large loudspeakers, and broadcasting political speeches from a makeshift radio studio aboard Hindenburg.[34]

On March 29, as German citizens voted overwhelmingly in favor of the Rhineland re-occupation, the Hindenburg was aloft over Berlin. Later, Hugo Eckener privately mocked Goebbels by telling friends, "There were forty persons on the Hindenburg. Forty-two 'yes' votes were counted." William Shirer recorded: "Goebbels has forbidden the press to mention Eckener's name."[35]

First commercial passenger flight

With the completion of voting on the referendum (which the German Government claimed had been approved by a "98.79% 'Yes' vote"),[36][37] Hindenburg returned to Löwenthal on March 29 to prepare for its first commercial passenger flight, a transatlantic passage to Rio de Janeiro scheduled to depart from there on March 31.[38] Hugo Eckener was not to be the commander of the flight, however, but was instead relegated to being a "supervisor" with no operational control over Hindenburg while Ernst Lehmann had command of the airship.[39] To add insult to injury, Eckener learned from an Associated Press reporter upon Hindenburg's arrival in Rio that Goebbels had also followed through on his month-old threat to decree that Eckener's name would "no longer be mentioned in German newspapers and periodicals" and "no pictures nor articles about him shall be printed."[40] This action was taken because of Eckener's opposition to using Hindenburg and Graf Zeppelin for political purposes during the Deutschlandfahrt, and his "refusal to give a special appeal during the Reichstag election campaign endorsing Chancellor Adolf Hitler and his policies."[41] The existence of the ban was never publicly acknowledged by Goebbels, and it was quietly lifted a month later.[42]

While at Rio, the crew noticed one of the engines had noticeable carbon buildup from having been run at low speed during the propaganda flight days earlier.[43] On the return flight from South America, the automatic valve for gas cell 3 stuck open.[44] Gas was transferred from other cells through an inflation line. It was never understood why the valve stuck open, and subsequently the crew used only the hand-operated maneuvering valves for cells 2 and 3. Thirty-eight hours after departure, one of the airship's four Daimler-Benz 16-cylinder diesel engines (engine car no. 4, the forward port engine) suffered a wrist pin breakage, damaging the piston and cylinder. Repairs were started immediately and the engine functioned on fifteen cylinders for the remainder of the flight. Four hours after engine 4 failed, engine no. 2 (aft port) was shut down, as one of two bearing cap bolts for the engine crankshaft failed and the cap fell into the crank case. The cap was removed and the engine was run again, but when the ship was off Cape Juby the second cap broke and the engine was shut down again. The engine was not run again to prevent further damage. With three engines operating at a speed of 100.7 km/h (62.6 mph) and headwinds reported over the English Channel, the crew raised the airship in search of counter-trade winds usually found above 1,500 metres (4,900 ft), well beyond the airship's pressure altitude. Unexpectedly, the crew found such a wind at the lower altitude of 1,100 metres (3,600 ft) which permitted them to guide the airship safely back to Germany after gaining emergency permission from France to fly a more direct route over the Rhone Valley. The nine-day flight covered 20,529 kilometres (12,756 mi) in 203 hours and 32 minutes of flight time.[45] All four engines were later overhauled and no further problems were encountered on later flights.[46] For the rest of April, Hindenburg remained at its hangar where the engines were overhauled and the lower fin and rudder received a final repair; the ground clearance of the lower rudder was increased from 8 to 14 degrees.

1936 transatlantic season

Hindenburg made 17 round trips across the Atlantic in 1936—its first and only full year of service—with ten trips to the United States and seven to Brazil. The flights were considered demonstrative rather than routine in schedule. The first passenger trip across the North Atlantic left Frankfurt on 6 May with 56 crew and 50 passengers, arriving in Lakehurst, New Jersey on 9 May. As the elevation at Rhein-Main's airfield lies at 111 m (364 ft) above sea level, the airship could lift 6 tonnes (13,000 lb) more at takeoff there than she could from Friedrichshafen, which was situated at 417 m (1,368 ft).[47] Each of the ten westward trips that season took 53 to 78 hours and eastward took 43 to 61 hours. The last eastward trip of the year left Lakehurst on October 10; the first North Atlantic trip of 1937 ended in the Hindenburg disaster.

In May and June 1936, Hindenburg made surprise visits to England. In May it was on a flight from America to Germany when it flew low over the West Yorkshire town of Keighley. A parcel was then thrown overboard and landed in the High Street. Two boys, Alfred Butler and Jack Gerrard, retrieved it and found the contents to be a bouquet of carnations, a small silver cross and a letter on official note paper dated May 22, 1936. The letter read: "To the finder of this letter, please deposit these flowers and cross on the grave of my dear brother, Lt. Franz Schulte, 1 Garde Regt, zu Fuss, POW in Skipton cemetery in Keighley near Leeds. Many thanks for your kindness. John P. Schulte, the first flying priest".[48][49] Historian Oliver Denton speculates that the June visit may have had a more sinister purpose: to observe the industrial heartlands of Northern England.[50]

In July 1936, Hindenburg completed a record Atlantic round trip between Frankfurt and Lakehurst in 98 hours and 28 minutes of flight time (52:49 westbound, 45:39 eastbound).[51] Many prominent people were passengers on the Hindenburg, including boxer Max Schmeling making his triumphant return to Germany in June 1936 after his world heavyweight title knockout of Joe Louis at Yankee Stadium.[52][53][54] In the 1936 season, the airship flew 191,583 miles (308,323 km) and carried 2,798 passengers and 160 tons of freight and mail, encouraging the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin Company to plan the expansion of its airship fleet and transatlantic service.[citation needed]

The airship was said to be so stable a pen or pencil could be balanced on end atop a table without falling. Launches were so smooth that passengers often missed them, believing the airship was still docked to the mooring mast. A one-way fare between Germany and the United States was US$400 (equivalent to $8,783 in 2023); Hindenburg passengers were affluent, usually entertainers, noted sportsmen, political figures, and leaders of industry.[55][56] Hindenburg was used again for propaganda when it flew over the Olympic Stadium in Berlin on August 1 during the opening ceremonies of the 1936 Summer Olympic Games. Shortly before the arrival of Adolf Hitler to declare the Games open, the airship crossed low over the packed stadium while trailing the Olympic flag on a long weighted line suspended from its gondola.[57] On September 14, the ship flew over the annual Nuremberg Rally.

On October 8, 1936, Hindenburg made a 10.5 hour flight (the "Millionaires Flight") over New England carrying 72 wealthy and influential passengers including financier and future U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom Winthrop W. Aldrich, his 28-year-old nephew Nelson Rockefeller, who became the Governor of New York and, later, Vice President of the United States, various German and American government officials and military officers, as well as key figures in the aviation industry, including Juan Trippe, founder and Chief Executive of Pan American Airways, and World War I flying ace Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, president of Eastern Airlines. The ship arrived at Boston by noon and returned to Lakehurst at 5:22 pm before making its final transatlantic flight of the season back to Frankfurt.[58]

During 1936, Hindenburg had a Blüthner aluminium grand piano placed on board in the music salon, though the instrument was removed after the first year to save weight.[59] Over the winter of 1936–37, several alterations were made to the airship's structures. The greater lift capacity allowed nine passenger cabins to be added, eight with two beds and one with four, increasing passenger capacity to 70.[60] These windowed cabins were along the starboard side aft of the previously installed accommodations, and it was anticipated for the LZ 130 to also have these cabins.[61] Additionally, the Olympic rings painted on the hull were removed for the 1937 season.

Hindenburg also had an experimental aircraft hook-on trapeze similar to the one on the U.S. Navy Goodyear–Zeppelin built airships Akron and Macon. This was intended to allow customs officials to be flown out to Hindenburg to process passengers before landing and to retrieve mail from the ship for early delivery. Experimental hook-ons and takeoffs, piloted by Ernst Udet, were attempted on March 11 and April 27, 1937, but were not very successful, owing to turbulence around the hook-up trapeze. The loss of the ship ended all prospects of further testing.[62]

Final flight: May 3–6, 1937

After making the first South American flight of the 1937 season in late March, Hindenburg left Frankfurt for Lakehurst on the evening of 3 May, on its first scheduled round trip between Europe and North America that season. Although strong headwinds slowed the crossing, the flight had otherwise proceeded routinely as it approached for a landing three days later.[63]

Hindenburg's arrival on 6 May was delayed for several hours to avoid a line of thunderstorms passing over Lakehurst, but around 7:00 pm the airship was cleared for its final approach to the Naval Air Station, which it made at an altitude of 200 m (660 ft) with Captain Max Pruss in command. At 7:21 pm a pair of landing lines were dropped from the nose of the ship and were grabbed hold of by ground handlers. Four minutes later, at 7:25 pm Hindenburg burst into flames and dropped to the ground in a little over half a minute. Of the 36 passengers and 61 crew aboard, 13 passengers[64] and 22 crew[65] died, as well as one member of the ground crew, a total of 36 lives lost.[66][67][68] Herbert Morrison's commentary of the incident became a classic of audio history.

The exact location of the initial fire, its source of ignition, and the source of fuel remain subjects of debate. The cause of the accident has never been determined conclusively, although many hypotheses have been proposed. Sabotage theories notwithstanding, one hypothesis often put forth involves a combination of gas leakage and atmospheric static conditions. Manually controlled and automatic valves for releasing hydrogen were located partway up one-meter diameter ventilation shafts that ran vertically through the airship.[69] Hydrogen released into a shaft, whether intentionally or because of a stuck valve, would have mixed with air already in the shaft — potentially in an explosive ratio. Alternatively, a gas cell could have been ruptured by the breaking of a structural tension wire causing a mixing of hydrogen with air.[70] The high static charge collected from flying within stormy conditions and inadequate grounding of the outer envelope to the frame could have ignited any resulting gas-air mixture at the top of the airship.[71] In support of the hypothesis that hydrogen was leaking from the aft portion of the Hindenburg prior to the conflagration, water ballast was released at the rear of the airship and six crew members were dispatched to the bow to keep the craft level.

Another more recent theory involves the airship's outer covering. The silvery cloth covering contained material with cellulose nitrate, which is highly flammable.[72] This theory is controversial and has been rejected by other researchers[73] because the outer skin burns too slowly to account for the rapid flame propagation[63] and gaps in the fire correspond with internal gas cell divisions, which would not be visible if the fire had spread across the skin first.[73] Hydrogen fires had previously destroyed many other airships.[74]

The duralumin framework of Hindenburg was salvaged and shipped back to Germany. There the scrap was recycled and used in the construction of military aircraft for the Luftwaffe, as were the frames of Graf Zeppelin and Graf Zeppelin II when they were scrapped in 1940.[75]

-

A partially burned piece of mail from the Hindenburg's last flight

-

Hindenburg on fire

-

A fire-scorched duralumin Hindenburg cross brace salvaged from the crash site

Appearances in media

- Charlie Chan was a passenger aboard the Hindenburg in the 1937 film Charlie Chan at the Olympics.

- An image of the burning airship was used as the cover of Led Zeppelin's self-titled debut album (1969).[76]

- The Hindenburg is a 1975 film inspired by the disaster, but centered on the sabotage theory. Some of these plot elements were based on real bomb threats before the flight began, as well as proponents of the sabotage theory. The actual model from the movie is now on permanent display in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

- In The Waltons 1977 episode "The Inferno", John Boy Walton is sent by a publication to cover the New Jersey landing, and is traumatized by witnessing the event.

- Hindenburg: The Last Flight is a 2011 German TV miniseries directed by Philipp Kadelbach. Like the 1975 film, it also focuses on the sabotage theory; the plot is about a young engineer who uncovers a plot to blow up the Hindenburg while the German airship is preparing for its maiden voyage to America.

Specifications

Data from Airships: A Hindenburg and Zeppelin History site[3]

General characteristics

- Crew: 40 to 61

- Capacity: 50–70[60] passengers

- Length: 245 m (803 ft 10 in)

- Diameter: 41 m (135 ft 1 in)

- Volume: 200,000 m3 (7,062,000 cu ft)

- Powerplant: 4 × Daimler-Benz DB 602 (LOF-6) V-16 diesel engines, 890 kW (1,200 hp) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 135 km/h (85 mph, 74 kn)

- Cruise speed: 122 km/h (76 mph, 66 kn)

See also

- Timeline of hydrogen technologies

- The Zeppelin Museum Friedrichshafen displays a reconstruction of a 33 m section of the Hindenburg.

Citations

- ^ Peter Hancock (2017). Transports of Delight: How Technology Materializes Human Imagination. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-3-319-55247-7.

- ^ List of Flights by D-LZ129 Hindenburg Airships.net

- ^ a b "Hindenburg Statistics." airships.net, 2009. Retrieved: July 22, 2017.

- ^ a b Grossman, Dan; Ganz, Cheryl; Russell, Patrick (2017). Zeppelin Hindenburg: An Illustrated History of LZ-129. The History Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0750969956.

- ^ "R101: the Final Trials and Loss of the Ship." The Airship Heritage Trust. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- ^ Lehmann 1937, p. 319.

- ^ Dick and Robinson 1985, p. 96.

- ^ "The Goodyear Zeppelin Company." Ohio History Central. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- ^ Dick and Robinson 1985, p. 97.

- ^ "LZ-129 The Latest Airship," Popular Mechanics, June 1935.

- ^ a b c MacGregor, Anne. "The Hindenburg Disaster: Probable Cause" (Documentary film). Moondance Films/Discovery Channel, Broadcast air date: 2001.

- ^ Grossman, Dan. "Hindenburg Design and Technology". Airships.net. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ^ Vaeth 2005, p. 38.

- ^ Sears 2015, pp. 108–113.

- ^ Lehmann 1937, p. 323.

- ^ "The Airship." British Quarterly Journal, Spring 1935.

- ^ Waibel, Barbara (2013). The Zeppelin airship LZ 129 Hindenburg. Sutton Verlag GmbH. ISBN 9783954003013.

- ^ "Today in History: Hindenburg’s First Flight, March 4, 1936." Airships.net. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- ^ "Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei (DZR)". Airships.net. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- ^ Lehmann 1937, pp. 323–332.

- ^ Lehmann 1937, p. 341.

- ^ "Hindenburg Begins First U.S. Flight." New York Times, May 7, 1936.

- ^ "Hindenburg is off on 2d U.S. Flight." New York Times, May 17, 1936.

- ^ "Hindenburg Flight Schedules." Airships.net. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- ^ "Propaganda 'attack' made by Zeppelins." The New York Times, March 29, 1936.

- ^ "Belgium Insistent on Locarno Terms", The New York Times, March 12, 1936.

- ^ "Two Reich Zeppelins on Election Tour", The New York Times, March 27, 1936.

- ^ Photograph of Hindenburg and Graf Zeppelin preparing to depart Löwenthal on Die Deutschlandfahrt. specialcollections.wichita.edu. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ William L. Shirer, Berlin Diary, ©1941 reprinted 2011 by Rosetta Books, entry for March 29, 1936

- ^ Lehmann 1937, p. 326.

- ^ Photograph by Harold Dick of damaged lower vertical tail fin. specialcollections.wichita.edu. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ Eckener 1958, pp. 150–151.

- ^ "Photograph by Harold Dick of temporary repair to lower vertical tail fin." specialcollections.wichita.edu. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ Lehmann 1937, pp. 326–332.

- ^ Berlin Diary, entry for April 1936 (undated)

- ^ "Hitler gets biggest vote: Many blanks counted in, 542,953 are invalidated. Some 'Noes' Not Counted; Confusion Causes Counting of Blanks and Many May Have Shown Opposition". The New York Times, March 30, 1936.

- ^ "Foreign News: May God Help Us!" Time, April 6, 1936

- ^ Mooney 1972, pp. 82–85.

- ^ "Transport: Von Hindenburg to Rio." Time, April 13, 1936.

- ^ Mooney 1972, p. 86.

- ^ "Eckener Refused Election Plea for Hitler: Name Barred From the Press as a Result." The New York Times, April 3, 1936.

- ^ "'Eckener's Disgrace Ends: Zeppelin Expert is Victor in Clash with Goebbels." The New York Times, April 30, 1936.

- ^ Dick and Robinson 1985, p. 119.

- ^ Dick and Robinson 1985, p. 118.

- ^ "Two Motors Crippled as Zeppelin Lands." The New York Times, April 11, 1936.

- ^ Lehmann 1937, pp. 341–342.

- ^ Lehmann 1937, p. 343.

- ^ George Bagshawe Harrison (1938), The Day Before Yesterday: Being a Journal of the Year 1936, Cobden-Sanderson, p. 121

- ^ "Flowers from Airship: "First Flying Priest's" Request", The Citizen, 61 (20), Gloucester: 4, May 23, 1936

- ^ Oliver Denton (2003), The Rose and the Swastika: The Story of the Hindenburg's Visits to Yorkshire in May and June 1936, Settle, West Yorkshire: Hudson History, ISBN 1903783224

- ^ "Hindenburg Flight Schedule" Airships.net

- ^ "Max Schmeling on the Hindenburg" Airships.net

- ^ "SCHMELING HOME, HAILED BY REICH Planes Soar Over Hindenburg to Greet Boxer Who Was Ignored on Departure" The New York Times, June 27, 1936

- ^ Berg, Emmett. "Fight of the Century." Archived March 10, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Humanities, Vol. 25, No. 4, July/August 2004. Retrieved: January 7, 2008.

- ^ Grossman, Dan. "Hindenburg's Maiden Voyage Passenger List" Airships.net. Retrieved: May 9, 2010.

- ^ Toland 1972, p. 9.

- ^ Birchall 1936

- ^ Grossman, Dan. "Hindenburg "Millionaires Flight"". Airships.net. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ "A History of the Blüthner Piano Company" Archived February 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine bluthnerpiano.com. Retrieved: January 7, 2008.

- ^ a b "The Hindenburg's Interior: Passenger Decks".

- ^ Bauer, Manfred; Duggan, John (1996). LZ 130 "Graf Zeppelin" and the End of Commercial Airship Travel. Friedrichshafen. ISBN 9783895494017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Dick and Robinson 1985, pp. 142–145.

- ^ a b Yoon, Joe (June 18, 2006). "Cause of the Hindenburg Disaster". Aero Space web. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ Hindenburg Disaster Passenger List Airships.net

- ^ Hindenburg Disaster – List of Officers and Crew Airships.net

- ^ Thompson, Craig. "Airship Like a Giant Torch On Darkening Jersey Field: Routine Landing Converted Into Hysterical Scene in Moment's Time—Witnesses Tell of 'Blinding Flash' From Zeppelin." The New York Times, May 7, 1937.

- ^ "The Hindenburg Disaster." Airships.net. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- ^ Morrison, Herbert. Live radio account of arrival and crash of Hindenburg. Radio Days via OTR.com. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- ^ Air Commerce Bulletin of August 15, 1937 (vol. 9, no. 2) published by the United States Department of Commerce

- ^ "The Hindenburg Accident. A Comparative Digest of the Investigations and Findings With the American and Translated German Reports Included." R.W. Knight, Acting Chief, Air Transport Section. U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Air Commerce, Safety and Planning Division, Report No. 11, August 1938.

- ^ Report of the German Investigation Commission about the Accident of the Airship "Hindenburg" on May 6, 1937, at Lakehurst, U.S.A.

- ^ Bokow, Jacquelyn Cochran (1997). "Hydrogen Exonerated in Hindenburg Disaster". National Hydrogen Association. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

The NHA's mission is to foster the development of hydrogen technologies and their utilization in industrial, commercial, and consumer applications and promote the role of hydrogen in the energy field.

- ^ a b Dessler, A. J. (June 3, 2004). "The Hindenburg Hydrogen Fire: Fatal Flaws in the Addison Bain Incendiary-Paint Theory" (PDF). John Dziadecki, Libraries Webmaster, University of Colorado, Boulder. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Grossman, Dan (October 2010). "Hydrogen Airship Disasters". airships.net. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Mooney 1972, p. 262.

- ^ Davis 1995, pp. 32, 44.

General sources

- Airships.net LZ-129 Hindenburg

- Airship Voyages Made Easy (16 page booklet for "Hindenburg" passengers). Friedrichshafen, Germany: Luftschiffbau Zeppelin G.m.b.H. (Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei), 1937.

- Archbold, Rick. Hindenburg: An Illustrated History. Toronto: Viking Studio/Madison Press, 1994. ISBN 0-670-85225-2.

- Birchall, Frederick. "100,000 Hail Hitler; U.S. Athletes Avoid Nazi Salute to Him". The New York Times, August 1, 1936, p. 1.

- Botting, Douglas. Dr. Eckener's Dream Machine: The Great Zeppelin and the Dawn of Air Travel. New York: Henry Holt & Co., 2001. ISBN 0-8050-6458-3.

- Davis, Stephen. Hammer of the Gods: The Led Zeppelin Saga (LPC). New York: Berkley Boulevard Books, 1995. ISBN 0-425-18213-4.

- Dick, Harold G. and Douglas H. Robinson. The Golden Age of the Great Passenger Airships Graf Zeppelin & Hindenburg. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985. ISBN 1-56098-219-5.

- Duggan, John. LZ 129 "Hindenburg": The Complete Story. Ickenham, UK: Zeppelin Study Group, 2002. ISBN 0-9514114-8-9.

- Eckener, Hugo, translated by Douglas Robinson. My Zeppelins. London: Putnam & Co. Ltd., 1958.

- Hindenburg's Fiery Secret (DVD). Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Video, 2000.

- Hoehling, A.A. Who Destroyed The Hindenburg? Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1962. ISBN 0-445-08347-6.

- Lehmann, Ernst. Zeppelin: The Story of Lighter-than-air Craft. London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1937.

- Majoor, Mireille. Inside the Hindenburg. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 2000. ISBN 0-316-12386-2.

- Mooney, Michael Macdonald. The Hindenburg. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1972. ISBN 0-396-06502-3.

- Provan, John. LZ-127 "Graf Zeppelin": The story of an Airship, vol. 1 & vol. 2 (Amazon Kindle ebook). Pueblo, Colorado: Luftschiff Zeppelin Collection, 2011.

- Sears, Wheeler M. "Bo" Jr. (2015). Helium: The Disappearing Element. New York: Springer. ISBN 9783319151236.

- Toland, John. The Great Dirigibles: Their Triumphs and Disasters. Mineola, New York: Dover Publishers, 1972.

- Vaeth, Joseph Gordon. They Sailed the Skies: U.S. Navy Balloons and the Airship Program. Annapolis Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1-59114-914-9.

External links

- The short film Giant Dirigible Sets Record, 1936/05/11 (1936) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Hindenburg – End Of A Successful Voyage (Standard 4:3) (1937), Pathgrams (film shows docking team, passengers)

- Hindenburg – Passengers Disembarking (Standard 4:3) (1937), Pathgrams (film of passengers descending ramp)

- Detailed Technical Drawing of the LZ 129 Hindenburg

- Airships.net: Detailed history and photographs of interior and exterior of LZ-129 Hindenburg

- "The Hindenburg Makes Her Last Landing at Lakehurst", Life Magazine article from 1937

- eZEP.de, The webportal for Zeppelin mail and airship memorabilia

- Hindenburg: Sky Cruise. Illustrated account of a flight on the Hindenburg – with maiden voyage and final flight passenger lists

- Harold G. Dick Airship Collection – lists of contents of the collection

- ZLT Zeppelin Luftschifftechnik GmbH & Co KG. The modern Zeppelin company

- The Hindenburg at Navy Lakehurst Historical Society

- "The Air Liners Of The Future." Popular Mechanics, February 1930, the future of dirigibles as aviation experts predicted in 1930, drawings on pages 220 and 221 shows how aviation experts saw the Hindenburg then under construction, including an overhead glass covered dance floor

- "Super-Zepp To Have All Luxuries Of A Liner."Popular Mechanics, July 1932, early drawing of future Hindenburg

- "Biggest Birds That Ever Flew." Popular Science, May 1962

- 75 Years Since The Hindenburg Disaster