Kotzebue, Alaska

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (September 2016) |

Kotzebue

Qikiqtaġruk | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Kotzebue | |

| Motto: "Gateway to the Arctic"

"An All American City" | |

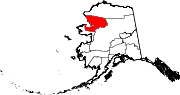

Location in Northwest Arctic Borough and the state of Alaska. | |

| Coordinates: 66°53′50″N 162°35′8″W / 66.89722°N 162.58556°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Alaska |

| Borough | Northwest Arctic |

| Incorporated | October 14, 1958[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-manager |

| • Mayor | Derek Haviland-Lie |

| • State senator | Donny Olson (D) |

| • State rep. | Thomas Baker (R) |

| Area | |

• Total | 26.50 sq mi (68.64 km2) |

| • Land | 24.76 sq mi (64.12 km2) |

| • Water | 1.75 sq mi (4.52 km2) |

| Elevation | 20 ft (6 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 3,102 |

| • Density | 125.30/sq mi (48.38/km2) |

| [3] | |

| Time zone | UTC−9 (AKST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−8 (AKDT) |

| ZIP code | 99752 |

| Area code | 907 |

| FIPS code | 02-41830 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1413378 |

| Website | City of Kotzebue, Alaska |

| |

Kotzebue (/ˈkɒtsəbjuː/ KOTS-ə-bew) or Qikiqtaġruk (/kɪkɪkˈtʌɡrʊk/ kik-ik-TUG-rook, Inupiaq: [qekeqtɑʁʐuk]) is a city in the Northwest Arctic Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. It is the borough's seat, by far its largest community and the economic and transportation hub of the subregion of Alaska encompassing the borough. The population of the city was 3,102 as of the 2020 census,[3] down from 3,201 in 2010.

History

Etymology and prehistory

Owing to its location and relative size, Kotzebue served as a trading and gathering center for the various communities in the region. The Noatak, Selawik and Kobuk Rivers drain into the Kotzebue Sound near Kotzebue to form a center for transportation to points inland. In addition to people from interior villages, inhabitants of far-eastern Asia, now the Russian Far East, came to trade at Kotzebue. Furs, seal-oil, hides, rifles, ammunition, and seal skins were some of the items traded. People also gathered for competitions like the current World Eskimo Indian Olympics. With the arrival of the whalers, traders, gold seekers, and missionaries the trading center expanded.

Kotzebue is also known as Qikiqtaġruk, which means "small island" or "resembles an island" in the Iñupiaq language.[4] In the words of the late Iñupiaq elder Blanche Qapuk Lincoln of Kotzebue:

Iḷiḷgaaŋukapta tamarra pamna imiqaqtuq. Taavaasii kuuqahuni taiñña Adams-kutlu Ipaaluk-kutlu, taapkuak piagun tavra. Taiñña suli Katyauratkutlu, Lena Norton tupqata piagun tavra kuuk suli taugani...Manna uvva qikiqtaq, Qikiqtaġruŋmik tavra atiqautiginiġaa qikiqtaupluni. Nunałhaiñġuqtuq marra pakma. ("When we were children there was water behind front street and a slough between the Ipalooks and Adams'. There was another slough over between Coppocks and Lena Norton's house...The island on Front Street led to Kotzebue being called Qikiqtaġruk because island in Iñupiaq is called qikiqtaq.").[5]

Kotzebue gets its name from the Kotzebue Sound, which was named after Otto von Kotzebue, a Baltic German who explored the sound while searching for the Northwest Passage in the service of Russia in 1818.

19th century

A United States post office was established in 1899.[6]

20th century

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2013) |

In 1958, Kotzebue Air Force Station was completed. The radar site would be operated by on-site personnel until its deactivation in 1983 and the subsequent demolition of most of the station's structures. The radome continues to operate, but is now mostly unattended.[7]

In 1990, the German drama film Salmonberries starring k.d. lang was mostly shot in Kotzebue.

In 1997, three 66-kw wind turbines were installed in Kotzebue, creating the northernmost wind farm in the United States. Today, the wind farm consists of 19 turbines, including two 900 kW EWT turbines. The total installed capacity has reached 3-MW, displacing approximately 250,000 gallons of diesel fuel every year.[8]

21st century

On September 2, 2015, U.S. President Barack Obama gave a speech on global warming in Kotzebue, becoming the first sitting president to visit a site north of the Arctic Circle.[9][10]

Since 2016, the United States Coast Guard has deployed MH-60 Jayhawk helicopters to Kotzebue from the beginning of July to the end of October as part of Operation Arctic Shield.[11][12]

In 2017, the city received an All-America City award from the National Civic League.[13]

On December 3, 2018, Mike Dunleavy was sworn in as the 12th governor of Alaska in Kotzebue's high school gymnasium after inclement weather thwarted his plan to hold the ceremony in Noorvik.[14]

In November 2023, ProPublica and Anchorage Daily News released an investigative report of domestic abuse and potential murders in Kotzebue involving six indigenous women who had dated Mayor Clement Richards Sr's three sons, resulting in a total of 16 charges that were ultimately dismissed by local prosecutors or received minimum sentences by local judicial magistrates.[15] While a state medical examiner stated for one of the women that there were "signs of strangulation", the local police eventually closed the case as suicide. In January 2024, the police released a statement saying they would not be re-opening the case, with their timeline of events in the statement contradicting events that occurred just after the woman's death. The city police said the other case of strangulation on the Mayor's property was referred to state investigators, though the Alaska Department of Public Safety said no such case was ever given to them.[16]

Geography

Kotzebue lies on a gravel spit at the end of the Baldwin Peninsula in the Kotzebue Sound. It is located at 66°53′50″N 162°35′8″W / 66.89722°N 162.58556°W (66.897192, −162.585444),[17] approximately 30 miles (48 km) from Noatak, Kiana, and other nearby smaller communities. It is 33 miles (53 km) north of the Arctic Circle on Alaska's western coast.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 28.7 square miles (74 km2), of which 27.0 square miles (70 km2) is land, and 1.6 square miles (4.1 km2), or 5.76%, is water.

Kotzebue is home to the NANA Regional Corporation, one of thirteen Alaska Native Regional Corporations created under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 (ANCSA) in settlement of Alaska Native land claims.

Kotzebue is a gateway to Kobuk Valley National Park and other natural attractions of northern Alaska. The Northwest Arctic Heritage Center, operated by the National Park Service, serves as a community meeting space and visitor center to Kobuk Valley National Park, Noatak National Preserve and Cape Krusenstern National Monument. Nearby Selawik National Wildlife Refuge also maintains office space in the town.[18]

Climate

Kotzebue has a dry subarctic climate (Köppen Dfc), with long, somewhat snowy, and very cold winters, and short, mild summers; diurnal temperature variation is low to minimal throughout the year, with an annual normal of 11.6 °F (6.4 °C) and a minimum normal of 8.0 °F (4.4 °C) in October.[19] Monthly daily average temperatures range from −1.9 °F (−18.8 °C) in January to 55.3 °F (12.9 °C) in July,[19] with an annual mean of 24.0 °F (−4.4 °C).[19] Days with the maximum reaching at or above 70 °F (21 °C) can be expected an average of six days per summer.[19] Precipitation is both most frequent and greatest during the summer months with August the wettest month averaging 2.13 in (54 mm). Kotzebue average precipitation is 11.36 in (289 mm) per year.[19] Snowfall averages about 64.2 in (163 cm) a season (July through June of the next year).[19] Extreme temperatures have ranged from −58 °F (−50 °C) on March 16, 1930, to 85 °F (29 °C) as recently as June 19, 2013.[19] The coldest has been January 1934 with a mean temperature of −27.3 °F (−32.9 °C), while the warmest month was July 2009 at 60.0 °F (15.6 °C);[a] the annual mean temperature has ranged from 16.5 °F (−8.6 °C) in 1964 to 29.7 °F (−1.3 °C) in 2016.[19]

| Climate data for Kotzebue Airport, Alaska (1991–2020 normals,[b] extremes 1897–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 40 (4) |

40 (4) |

42 (6) |

49 (9) |

74 (23) |

85 (29) |

85 (29) |

80 (27) |

69 (21) |

57 (14) |

40 (4) |

39 (4) |

85 (29) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 30.8 (−0.7) |

31.2 (−0.4) |

30.0 (−1.1) |

39.0 (3.9) |

56.1 (13.4) |

71.4 (21.9) |

73.5 (23.1) |

68.4 (20.2) |

59.6 (15.3) |

43.8 (6.6) |

32.4 (0.2) |

29.2 (−1.6) |

76.0 (24.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 4.5 (−15.3) |

8.6 (−13.0) |

9.1 (−12.7) |

23.8 (−4.6) |

39.0 (3.9) |

53.2 (11.8) |

60.1 (15.6) |

56.6 (13.7) |

47.5 (8.6) |

30.8 (−0.7) |

15.9 (−8.9) |

8.6 (−13.0) |

29.8 (−1.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | −1.9 (−18.8) |

1.4 (−17.0) |

1.5 (−16.9) |

16.3 (−8.7) |

33.1 (0.6) |

47.5 (8.6) |

55.3 (12.9) |

52.1 (11.2) |

43.1 (6.2) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

10.8 (−11.8) |

2.4 (−16.4) |

24.0 (−4.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | −8.4 (−22.4) |

−5.8 (−21.0) |

−6.0 (−21.1) |

8.8 (−12.9) |

27.3 (−2.6) |

41.8 (5.4) |

50.5 (10.3) |

47.7 (8.7) |

38.7 (3.7) |

23.0 (−5.0) |

5.6 (−14.7) |

−3.8 (−19.9) |

18.3 (−7.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −34.0 (−36.7) |

−31.0 (−35.0) |

−26.7 (−32.6) |

−13.6 (−25.3) |

10.8 (−11.8) |

30.5 (−0.8) |

41.6 (5.3) |

38.5 (3.6) |

27.8 (−2.3) |

6.4 (−14.2) |

−14.4 (−25.8) |

−26.0 (−32.2) |

−37.4 (−38.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −55 (−48) |

−52 (−47) |

−58 (−50) |

−44 (−42) |

−18 (−28) |

20 (−7) |

30 (−1) |

26 (−3) |

13 (−11) |

−19 (−28) |

−37 (−38) |

−49 (−45) |

−58 (−50) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.62 (16) |

0.85 (22) |

0.52 (13) |

0.56 (14) |

0.44 (11) |

0.60 (15) |

1.60 (41) |

2.13 (54) |

1.42 (36) |

1.07 (27) |

0.82 (21) |

0.73 (19) |

11.36 (289) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 9.4 (24) |

13.1 (33) |

6.4 (16) |

4.7 (12) |

1.2 (3.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.6 (1.5) |

5.9 (15) |

11.0 (28) |

11.9 (30) |

64.2 (163) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.6 | 9.8 | 7.3 | 6.7 | 7.0 | 6.1 | 11.1 | 13.5 | 11.8 | 11.5 | 9.6 | 10.3 | 113.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 9.5 | 10.4 | 7.8 | 6.2 | 2.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 7.1 | 9.9 | 11.4 | 65.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72.0 | 70.2 | 71.1 | 76.3 | 81.2 | 81.8 | 80.7 | 81.2 | 79.2 | 79.1 | 76.5 | 73.7 | 76.9 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | −7.1 (−21.7) |

−11.9 (−24.4) |

−6.5 (−21.4) |

5.7 (−14.6) |

25.9 (−3.4) |

37.8 (3.2) |

47.7 (8.7) |

46.2 (7.9) |

35.6 (2.0) |

17.4 (−8.1) |

2.1 (−16.6) |

−7.2 (−21.8) |

15.5 (−9.2) |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity 1961–1990)[19][22][23] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas[24] | |||||||||||||

| Coastal temperature data for Kotzebue | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 29.7 (-1.28) |

30.0 (-1.11) |

29.3 (-1.50) |

29.1 (-1.61) |

29.8 (-1.22) |

32.9 (0.50) |

47.3 (8.50) |

52.7 (11.50) |

48.0 (8.89) |

39.9 (4.39) |

29.8 (-1.22) |

28.6 (-1.89) |

35.6 (2.00) |

| Source 1: Seatemperature.net[25] | |||||||||||||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. Updates on reimplementing the Graph extension, which will be known as the Chart extension, can be found on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit raw graph data.

- Notes

- ^ The July 2019 average measured an average temperature of 63.7 °F (17.6 °C), but NOAA later rescinded its recognition of the temperature record and deleted the May–August 2019 temperature data from its database.[20][21]

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 200 | — | |

| 1910 | 193 | — | |

| 1920 | 230 | 19.2% | |

| 1930 | 291 | 26.5% | |

| 1940 | 372 | 27.8% | |

| 1950 | 623 | 67.5% | |

| 1960 | 1,290 | 107.1% | |

| 1970 | 1,696 | 31.5% | |

| 1980 | 2,054 | 21.1% | |

| 1990 | 2,751 | 33.9% | |

| 2000 | 3,082 | 12.0% | |

| 2010 | 3,201 | 3.9% | |

| 2020 | 3,102 | [3] | −3.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[26][failed verification] | |||

Kotzebue first appeared on the 1880 U.S. Census under its predecessor unincorporated Inuit village named "Kikiktagamute."[27] It did not appear again until 1910, then as Kotzebue. It formally incorporated in 1958.

As of the census[28][failed verification] of 2000,[needs update] there were 3,082 people, 889 households, and 656 families residing in the city. The population density was 114.1 inhabitants per square mile (44.1/km2). There were 1,007 housing units at an average density of 37.3 per square mile (14.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 71.2% American Indian, 19.5% White, 1.8% Asian, 0.3% Black or African American, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.8% from other races, and 6.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.2% of the population.

There were 889 households, out of which 50.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.1% were married couples living together, 17.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.1% were non-families. 19.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 2.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.40 and the average family size was 3.93.

In the city, the age distribution of the population shows 39.8% under the age of 18, 8.5% from 18 to 24, 30.4% from 25 to 44, 17.2% from 45 to 64, and 4.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 26 years. For every 100 females, there were 102.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 104.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $57,163, and the median income for a family was $58,068. Males had a median income of $42,604 versus $36,453 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,289. About 9.2% of families and 13.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 14.9% of those under age 18 and 6.0% of those age 65 or over.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Kotzebue's Ralph Wien Memorial Airport is the one airport in the Northwest Arctic Borough with regularly scheduled large commercial passenger aircraft service to and from Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport and the Nome Airport.

Health care

Kotzebue is home to the Maniilaq Association, a tribally-operated health and social services organization named after Maniilaq and part of the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. Maniilaq Health Center is the primary health care facility for the residents of the Northwest Arctic Borough. The facility houses an emergency room with local and medevac support for accident/trauma victims, as well as an ambulatory care clinic, dental and eye care clinics, a pharmacy, a specialty clinic, and an inpatient wing with 17 beds for recovering patients.

Health care providers at Maniilaq Health Center provide telemedicine support to Community Health Aides (CHAPs) in the outlying villages of the Northwest Arctic Borough. The CHAPs, who work in village-based clinics, are trained in basic health assessment and can treat common illnesses. For more complicated cases, the CHAPs communicate with Maniilaq Health Center medical staff via phone, video-conference, and digital images.

Media

The Arctic Sounder is a weekly newspaper published by Alaska Media, LLC, which covers Kotzebue and the rest of the Northwest Arctic Borough along with the North Slope Borough (and its hub community of Utqiagvik).

KOTZ, broadcasting at 720 on the AM dial, is the public radio station serving Kotzebue, one of two Class A clear-channel stations in the United States at that frequency (the other being Chicago's WGN). KOTZ operates an extensive translator network serving the rest of the borough.

Education

Northwest Arctic Borough School District operates two schools in Kotzebue: June Nelson Elementary School (JNES) and Kotzebue Middle High School (KMHS). As of 2017[update] they had 394 and 309 students, making them the largest schools in the district.[29]

There is one private school run by the Native Village of Kotzebue called Nikaitchuat Iḷisaġviat. It is an Inupiaq language immersion school for grades PK through one.

University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) operates their Chukchi Campus which offers classes, a library and other community services.

Notable people

- Willie Hensley (born 1941), former state Representative, former state Senator, one of key founders of NANA Regional Corporation, instrumental in the passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act

- Reggie Joule (born 1952), who represented Kotzebue and surrounding area in the Alaska House of Representatives for eight terms followed by a single term as borough mayor, achieved minor national fame during the 1970s and 1980s for his exploits in the World Eskimo Indian Olympics, including two appearances on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson

- Seth Kantner, novelist

- John Lincoln (born 1981), member of the Alaska House of Representatives

- Segundo Llorente (1906–1989), Spanish-born Jesuit, philosopher, author and politician

- Adam Stennett (born 1972), painter

- John Baker (c. 1962), winner of the 2011 Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race

Toxins

Although no "toxic releases" come from within the bounds of Kotzebue, the methods used by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)'s in their Toxic Releases Inventory (TRI) reports that in 2016, Kotzebue, with only 7,500 inhabitants, "produced" 756 million pounds of toxins.(Due to the way the EPA defines toxins, even the discharge of filtered and pH balanced water is called a toxin.) The TRI placed Kotzebue as the most toxic place in the United States. The second most toxic was Bingham Canyon, Utah at 200 million pounds of toxins. However, as National Geographic explains, the source of the toxins is not Kotzebue, but Alaska's Red Dog mine.[30] Since the mine is located in a remote area in Alaska, the toxic release is linked to the nearest "city"— Kotzebue.[30] The EPA says that when a "facility" is "not located in a city, town, village, or similar entity will often list a nearby city." National Geographic says that, "All 756 million pounds of toxic chemicals attributed to "Kotzebue" on the TRI dataset came from one of the world's largest zinc and lead mines, the Red Dog mine, which is located about 80 miles north of Kotzebue."[30] At the county level the Northwest Arctic of Alaska leads the list with 756,000,000 pounds of toxins. The state of Alaska produces three times more toxins than every other American state—834 million pounds.[31]

References

- ^ 1996 Alaska Municipal Officials Directory. Juneau: Alaska Municipal League/Alaska Department of Community and Regional Affairs. January 1996. p. 86.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c "2020 Census Data - Cities and Census Designated Places" (Web). State of Alaska, Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ Lincoln, Blanche Qapuk. Lore of the Iñupiat: The Elders Speak (Vol. 3). 1992. p. 235.

- ^ Lincoln, Blanche Qapuk. Lore of the Iñupiat: The Elders Speak (Vol. 3). 1992. p. 234-235.

- ^ Dickerson, Ora B. (1989) 120 Years of Alaska Postmasters, 1867–1987, p. 44. Scotts, Michigan: Carl J. Cammarata

- ^ Denfeld, D. Colt Ph.D. (1994). The Cold War in Alaska: A Management Plan for Cultural Resources (PDF). United States Army Corps of Engineers. pp. 158–159. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 17, 2021.

- ^ "The northernmost wind farm in the United States". NANA Regional Corporation, Inc. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- ^ "Obama, Visiting Arctic, Will Pledge Aid to Alaskans Hit by Climate Change". New York Times. September 2, 2015. Retrieved September 2, 2015.

- ^ "In Alaska, Obama becomes 1st president to enter the Arctic". Yahoo News. September 3, 2015. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- ^ "Coast Guard launches seasonal home base in Kotzebue". Anchorage Daily News. June 26, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ Rosen, Yereth (July 5, 2021). "US Coast Guard starts its seasonal Arctic operations from Kotzebue base". ArcticToday. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ "Kotzebue".

- ^ "Dunleavy sworn in as governor after a very Alaska travel glitch". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Hopkins, Kyle (November 11, 2023). "One Woman Died on an Alaska Mayor's Property. Then Another. No One Has Ever Been Charged". ProPublica. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ^ Hopkins, Kyle (January 30, 2024). "Police Say They Won't Reopen Case of Alaska Woman Found Dead on Mayor's Property". ProPublica. Retrieved January 30, 2024.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Kobuk Valley National Park". U.S. National Park Service. January 20, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ "tn70133_1yr". cpc.ncep.noaa.gov. NOAA. May 19, 2023. Archived from the original on May 19, 2023.

- ^ "JUILLET 2019 À KOTZEBUE". meteo-climat-bzh.dyndns.org (in French). May 10, 2023.

- ^ "Station Name: AK KOTZEBUE AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 6, 2023. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for KOTZEBUE/RALPH WIEN, AK 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 4, 2023. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- ^ "Kotzebue, Alaska, USA - Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". NOAA. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "Kotzebue Sea Temperature". seatemperature.net. April 30, 2023. Archived from the original on April 30, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Geological Survey Professional Paper". 1949.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Home. June Nelson Elementary School. Retrieved on March 26, 2017.

- ^ a b c Nobel, Justin (February 21, 2018). "America's Most 'Toxics-Releasing' Facility Is Not Where You'd Think". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- ^ Priceonomics (November 7, 2017). "The Most (And Least) Toxic Places In America". Forbes. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

Further reading

- Anderson, Douglas D., and Robert A. Henning. The Kotzebue Basin. Alaska geographic, v. 8, no. 3. Anchorage: Alaska Geographic Society, 1981. ISBN 978-0-88240-157-7

- Giddings, J. Louis, and Douglas D. Anderson. Beach Ridge Archeology of Cape Krusenstern Eskimo and Pre-Eskimo Settlements Around Kotzebue Sound, Alaska. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, 1986.

- Lucier, Charles V., and James W. VanStone. Traditional Beluga Drives of the Iñupiat of Kotzebue Sound, Alaska. Fieldiana, new ser., no. 25. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History, 1995.

External links

- Official website of the City of Kotzebue