Jubal Early

Jubal Early | |

|---|---|

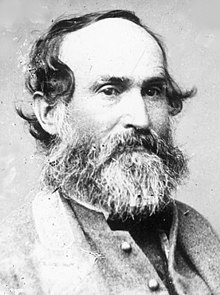

Early, c. 1861–1865 | |

| Member of the Virginia House of Delegates from Franklin County | |

| In office 1841–1842 | |

| Preceded by | Wyley P. Woods |

| Succeeded by | Norborne Taliaferro |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Jubal Anderson Early November 3, 1816 Franklin County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | March 2, 1894 (aged 77) Lynchburg, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Spring Hill cemetery, Lynchburg |

| Political party | Whig |

| Relatives | John Early (1st cousin twice removed) |

| Alma mater | United States Military Academy |

| Profession |

|

| Signature | |

| Nickname(s) | "Old Jube" "Old Jubilee" "Bad Old Man" |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank |

|

| Commands | |

| Battles/wars | |

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was an American lawyer, politician and military officer who served in the Confederate States Army during the Civil War.[1] Trained at the United States Military Academy, Early resigned his United States Army commission after the Second Seminole War and his Virginia military commission after the Mexican–American War, in both cases to practice law and participate in politics. Accepting a Virginia and later Confederate military commission as the American Civil War began, Early fought in the Eastern Theater throughout the conflict. He commanded a division under Generals Stonewall Jackson and Richard S. Ewell, and later commanded a corps.

A key Confederate defender of the Shenandoah Valley, during the Valley campaigns of 1864, Early made daring raids to the outskirts of Washington, D.C., and as far as York, Pennsylvania, but was eventually pushed back by Union Army troops led by General Philip Sheridan, losing over half his forces. After the war, Early fled to Mexico, then Cuba and Canada, and upon returning to the United States took pride as an "unrepentant rebel." Particularly after the death of Gen. Robert E. Lee in 1870, Early delivered speeches establishing the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, cofounding the Southern Historical Society and several Confederate memorial associations.[2]

Early life and family

Early was born on November 3, 1816, in the Red Valley section of Franklin County, Virginia, third of ten children of Ruth (née Hairston) (1794–1832) and Joab Early (1791–1870). The Early family was well-established and well-connected in the area, either one of the First Families of Virginia, or linked to them by marriage as they moved westward toward the Blue Ridge Mountains from Virginia's Eastern Shore. His great-grandfather, Col. Jeremiah Early (1730–1779) of Bedford County, Virginia, bought an iron furnace in Rocky Mount (in what became Franklin County) with his son-in-law Col. James Calloway, but soon died. He willed it to his sons Joseph, John, and Jubal Early (grandfather of the present Jubal A. Early, named for his grandfather). Of those men, only John Early (1773–1833) would live long and prosper—he sold his interest in the furnace and bought a plantation from his father-in-law in Albemarle County. Earlysville, Virginia, was named after him.[3] Jubal Early (for whom the baby Jubal was named) only lived a couple of years after his marriage. His young sons Joab (this Early's father) and Henry became wards of Col. Samuel Hairston (1788–1875), a major landowner in southwest Virginia, and in 1851 reputedly the richest man in the South, worth $5 million (~$146 million in 2023) in land and enslaved people.[4][5][6]

Joab Early married his mentor's daughter, as well as like him (and his own son, this Jubal Early), served in the Virginia House of Delegates part-time (1824–1826), and become the county sheriff and led its militia, all while managing his extensive tobacco plantation of more than 4,000 acres using enslaved labor.[7] His eldest son Samuel Henry Early (1813–1874) became a prominent manufacturer of salt using enslaved labor in the Kanawha Valley (of what became West Virginia during the American Civil War), and was a Confederate officer. Samuel H. Early married Henrian Cabell (1822–1890); their daughter, Ruth Hairston Early (1849–1928), became a prominent writer, member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and preservationist in Lynchburg, which became her family's home before the American Civil War and this Jubal Early's base during his final decades.[8] His slightly younger brother Robert Hairston Early (1818–1882) also served as a Confederate officer during the Civil War but moved to Missouri.

Jubal Early had the wherewithal to attend local private schools in Franklin County, as well as more advanced private academies in Lynchburg and Danville. He was deeply affected by his mother's death in 1832. The following year, his father and Congressman Nathaniel Claiborne secured a place in the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, for young Early, citing his particular aptitude for science and mathematics. He passed probation and became the first boy from Franklin County to enter the Military Academy.[9] Early graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1837, ranked 18th of 50 graduating cadets and sixth among its engineering graduates.[10] During his tenure at the Academy, fellow cadet Lewis Addison Armistead broke a mess plate over Early's head, which prompted Armistead's departure from the Academy, although he, too, became an important Confederate officer.[11] Other future generals in that 1837 class were Union generals Joseph Hooker (with whom Early would have a verbal mess hall altercation over slavery), John Sedgwick and William H. French, as well as future Confederate generals Braxton Bragg, John C. Pemberton, Arnold Elzey and William H. T. Walker. Other future generals whose time at West Point also overlapped with Early's included P.G.T. Beauregard, Richard Ewell, Edward "Allegheny" Johnson, Irwin McDowell and George Meade.[12]

Early military, legal and political careers

Upon graduating from West Point, Early received a commission as a second lieutenant in the 3rd U.S. Artillery regiment. Assigned to fight against the Seminole in Florida, he was disappointed that he never even saw a Seminole and merely heard "some bullets whistling among the trees" not close to his position. His elder brother Samuel counseled him to finish his statutory one-year obligation, then return to civilian life. Thus Early resigned from the Army for the first time in 1838, later commenting that if notice of a promotion that reached him in Louisville during his return to Virginia had come earlier, he might have withheld that letter of resignation.[13]

Early studied law with local attorney Norborne M. Taliaferro and was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1840. Franklin County voters the next year elected Early as one of their delegates in the Virginia House of Delegates (a part-time position); he was a Whig and served one term alongside Henry L. Muse from 1841 to 1842.[14] After redistricting reduced Franklin County's representation, his mentor (but Democrat) Norborne M. Taliaferro was elected to succeed him (and was re-elected many times until 1854, as well as become a local judge).[15] Meanwhile, voters elected Early to succeed Talliaferro as Commonwealth's attorney (prosecutor) for both Franklin and Floyd Counties; he was re-elected and served until 1852, apart from leading other Virginia volunteers during the Mexican–American War as noted below.[16]

During the Mexican–American War (despite the opposition of prominent Whig Henry Clay to that war), Early volunteered and received a commission as a Major with the 1st Virginia Volunteers. During Early's time at West Point, he had considered resigning in order to fight for Texas' independence, but had been dissuaded by his father and elder brother.[17] He served from 1847 to 1848, although his Virginians arrived too late to see battlefield combat. Major Early was assigned to logistics, as inspector general on the brigade's staff under West Pointers Col. John F. Hamtramck[18] and Lt. Col. Thomas B. Randolph, and later helped govern the town of Monterrey, bragging that the good conduct of his men won universal praise and produced better order in Monterrey than ever before, as well as that by the time they were mustered out of service at Fort Monroe, many of his men conceded that they had misjudged him at the beginning. While in Mexico, Early met Jefferson Davis, who commanded the first Mississippi Volunteers, and they exchanged compliments. During the winter in damp northern Mexico, Early experienced the first attacks of the rheumatoid arthritis that plagued him for the rest of his life, and he was even sent home for three months to recover.[19]

However, his legal career was not particularly remunerative when he returned although Early won an inheritance case in Lowndes County, Mississippi. He handled many cases involving slaves as well as divorces, but owned one slave during his life. In the 1850 census, Early owned no real estate and lived in a tavern, as did several other lawyers; likewise, in the 1860 census, he owned neither real nor personal property (such as slaves) and lived in a hotel, as did several other lawyers and merchants.[20] During this time, Early lived with Julia McNealey, who bore him four children whom Early acknowledged as his (including Jubal L. Early). She married another man in 1871. A biographer characterized Early as both unconventional and contrarian, "yet wedded to stability and conservatism".[21]

Although Early failed to win election as Franklin County's delegate to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1850, Franklin County voters elected Early and Peter Saunders (who lived in the same boardinghouse, although the son of prominent local landowner Samuel Sanders) to represent them at the Virginia Secession Convention of 1861.[22] A staunch Unionist, Early argued that the rights of Southerners without slaves were worth protection as much as those who owned slaves and that secession would precipitate war. Despite being mocked as "the Terrapin from Franklin," Early strongly opposed secession during both votes (Saunders left before the second vote, which approved secession).[16]

American Civil War

However, when President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion, Early fumed. After Virginia voters ratified secession, like many of his cousins, he accepted a commission to serve against the U.S. Army. Initially, Early became a brigadier general in the Virginia Militia and was sent to Lynchburg, where he raised three regiments and then commanded one of them. On June 19, 1861, Early formally became a colonel in the Confederate army, commanding the 24th Virginia Infantry, including his young cousin (previously expelled from Virginia Military Institute (VMI) for attending a tea party), Jack Hairston.[23]

After the First Battle of Bull Run (also called the First Battle of Manassas) in July 1861, Early was promoted to brigadier general, because his valor at Blackburn's Ford impressed General P.G.T. Beauregard, and his troops' charge along Chinn Ridge helped rout the Union forces (although his cousin Cpt. Charles Fisher of the 6th North Carolina died supporting the assault).[24][25] As general, Early led Confederate troops in most of the major battles in the Eastern Theater, including the Seven Days Battles, the Second Battle of Bull Run, the Battle of Antietam, the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Battle of Chancellorsville, the Battle of Gettysburg, and numerous battles in the Shenandoah Valley during the Valley Campaigns of 1864.

General Robert E. Lee, the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, affectionately called Early his "Bad Old Man" because of his short temper, insubordination, and use of profanity. Lee also appreciated Early's aggressive fighting and ability to command units independently. Most of Early's soldiers (except during the war's last days) referred to him as "Old Jube" or "Old Jubilee" with enthusiasm and affection. (The "old" referred to a stoop because of the rheumatism incurred in Mexico.)[26] His subordinate officers often experienced Early's inveterate complaints about minor faults and biting criticism at the least opportunity. Generally blind to his own mistakes, Early reacted fiercely to criticism or suggestions from below.[27]

Serving under Stonewall Jackson

As the Union Peninsular Campaign began in May 1862, Early, without adequate reconnaissance, led a futile charge through a swamp and wheat field against two Union artillery redoubts at what became known as the Battle of Williamsburg.[16] His 22 year old cousin Jack Hairston was killed. The 24th Virginia suffered 180 killed, wounded or missing in the battle; Early himself received a shoulder wound and convalesced near home in Rocky Mount, Virginia.[28] On June 26, the first day of the Seven Days Battles, Early reported himself ready for duty. The brigade he had commanded at Williamsburg no longer existed, having suffered severe casualties in that assault and an army reorganization assigned the remaining men whose enlistments continued to other units. General Lee informed Early that he could not be assigned a new command in the middle of battle and recommended for Early to wait until an opening came up somewhere. On July 1, just in time for the Battle of Malvern Hill (the last engagement in the Seven Days Battles), Early (though still unable to mount a horse without assistance) received command of Brig. Gen. Arnold Elzey's brigade because Elzey had been wounded at the Battle of Gaines Mill and the ranking colonel, James Walker, seemed too inexperienced for brigade command.[29] The brigade was not engaged in the battle.

For the rest of 1862, Early commanded troops within the Second Corps under General Stonewall Jackson. During the Northern Virginia Campaign, Early's immediate superior was Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell. Early received accolades for his performance at the Battle of Cedar Mountain. His troops arrived in the nick of time to reinforce Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill on Jackson's left on Stony Ridge during the Second Battle of Bull Run (Second Manassas).

At the Battle of Antietam, Early ascended to division command when his commander, Alexander Lawton, was wounded on September 17, 1862, after Lawton had assumed that division command while Maj. Gen. Ewell recovered after a wound received at Second Manassas caused amputation of his leg. At Fredericksburg, Early and his troops saved the day by counterattacking the division of Maj. Gen. George Meade, which penetrated a gap in Jackson's lines. Impressed by Early's performance, Gen. Lee retained him as commander of what had been Ewell's division; Early formally received a promotion to major general on January 17, 1863.

During the Chancellorsville campaign, which began on May 1, 1863, Lee gave Early 9,000 men to defend Fredericksburg at Marye's Heights against superior forces (4 divisions) under Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick.[30] Early was able to delay the Union forces and pin down Sedgwick while Lee and Jackson attacked the rest of the Union troops to the west. Sedgwick's eventual attack on Early up Marye's Heights on May 3, 1863, is sometimes known as the Second Battle of Fredericksburg. After the battle, Early engaged in a newspaper war with Brig. Gen. William Barksdale of Mississippi (a former newspaperman and congressman), who had commanded a division under Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws in the First Corps, until Gen. Lee told the two officers to stop their public feud. Jackson died on May 10, 1863, of a wound received from his own sentry on the night of May 2, 1863, and the recovered Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell assumed command of the Second Corps.

Gettysburg and Overland Campaign

During the Gettysburg Campaign of mid-1863, Early continued to command a division in the Second Corps under Lt. Gen. Ewell. His troops were instrumental in overcoming Union defenders at the Second Battle of Winchester on June 13–15. They captured many prisoners, and opened up the Shenandoah Valley for Lee's forces. Early's division, augmented with cavalry, eventually marched eastward across the South Mountain into Pennsylvania, seizing vital supplies and horses along the way. Early captured Gettysburg on June 26 and demanded a ransom, which was never paid. He threatened to burn down any home which harbored a fugitive slave. Two days later, he entered York County and seized York. Here, his ransom demands were partially met, including $28,000 in cash. York thus became the largest Northern town to fall to the Rebels during the war. He also burned an iron foundry near Caledonia owned by abolitionist U.S. Representative Thaddeus Stevens.[31] Elements of Early's command on June 28 reached the Susquehanna River, the farthest east in Pennsylvania that any organized Confederate force could penetrate. On June 30, Early was recalled to join the main force as Lee concentrated his army to meet the oncoming Federals. Troops under Early's command were also responsible for capturing escaped slaves to send them back to the south, which resulted in the seizure of free Blacks who were unable to evade the invading army. Over 500 Black people were abducted from southern Pennsylvania.[32]

Approaching the Gettysburg battlefield from the northeast on July 1, 1863, Early's division was on the left flank of the Confederate line. He soundly defeated Brig. Gen. Francis Barlow's division (part of the Union XI Corps), inflicting three times the casualties to the defenders as he suffered, and drove the Union troops back through the streets of the town, capturing many of them. This later became another controversy, as Lt. Gen. Ewell denied Early permission to assault East Cemetery Hill to which Union troops had retreated. When the assault was allowed the following day as part of Ewell's efforts on the Union right flank, it failed with many casualties. The delay allowed Union reinforcements to arrive, which repulsed Early's two brigades. On the third day of battle, Early detached one brigade to assist Maj. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's division in an unsuccessful assault on Culp's Hill. Elements of Early's division covered the rear of Lee's army during its retreat from Gettysburg on July 4 and July 5.[16]

Early's forces wintered in the Shenandoah Valley in 1863–64. During this period, he occasionally filled in as corps commander when Ewell's illness forced absences. On May 31, 1864, Lee expressed his confidence in Early's initiative and abilities at higher command levels. With Confederate President Jefferson Davis now being authorized to make temporary promotions; on Lee's request Early was promoted to the temporary rank of lieutenant general.[33][34]

Early fought well during the inconclusive Battle of the Wilderness (during which a cousin died), and assumed command of the ailing A.P. Hill's Third Corps during the march to intercept Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Spotsylvania Court House. At Spotsylvania, Early occupied the relatively quiet right flank of the Mule Shoe. After Hill had recovered and resumed command, Lee, dissatisfied with Ewell's performance at Spotsylvania, assigned him to defend Richmond and gave Early command of the Second Corps. Thus, Early commanded that corps in the Battle of Cold Harbor.

Union Gen. David Hunter had burned the VMI in Lexington on June 11, and was raiding through the Shenandoah Valley, the Confederate breadbasket, so Lee sent Early and 8,000 men to defend Lynchburg, an important railroad hub (with links to Richmond, the Valley and points southwest) as well as many hospitals for recovering Confederate wounded. John C. Breckinridge, Arnold Elzey and other convalescing Confederates and the remains of VMI's cadet corps assisted Early and his troops, as did many townspeople, including Narcissa Chisholm Owen, wife of the president of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. Using a ruse involving trains entering town to exaggerate his strength, Early convinced Hunter to retreat toward West Virginia on June 18, in what became known as the Battle of Lynchburg, although the pursuing Confederate cavalry were soon outrun.[35]

Shenandoah Valley, 1864–1865

During the Valley Campaigns of 1864, Early received a temporary promotion to lieutenant general and command of the "Army of the Valley" (the nucleus of which was the former Second Corps). Thus Early commanded the Confederacy's last invasion of the North, secured much-needed funds and supplies for the Confederacy and drawing off Union troops from the siege of Petersburg. Since Union armies under Grant and Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman were rapidly capturing formerly Confederate territory, Lee sent Early's corps to sweep Union forces from the Shenandoah Valley, as well as to menace Washington, D.C. He hoped to secure supplies as well as compel Grant to dilute his forces against Lee around the Confederate capital at Richmond and its supply hub at Petersburg.

Early delayed his march for several days in a futile attempt to capture a small force under Franz Sigel at Maryland Heights near Harpers Ferry.[36] His men then rested and ate captured Union supplies from July 4 through July 6.[37] Although elements of his army reached the outskirts of Washington at a time when it was largely undefended, his delay at Maryland Heights and from extorting money from Hagerstown and Frederick, Maryland, prevented him from being able to attack the federal capital. Residents of Frederick paid $200,000 ($3.9 million in 2023 dollars[38]) on July 9 and avoided being sacked,[39] supposedly because some women had booed Stonewall Jackson's troops on their trip through town the previous year (the city had divided loyalties and later erected a Confederate Army monument).[40] Later in the month, Early attempted to extort funds from Cumberland and Hancock, Maryland, and his cavalry commanders burned Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, when that city could not pay sufficient ransom.[41]

Meanwhile, Grant sent two VI Corps divisions from the Army of the Potomac to reinforce Union Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace defending the railroad to Washington, D.C. With 5,800 men, Wallace delayed Early for an entire day at the Battle of Monocacy Junction outside Frederick, which allowed additional Union troops to reach Washington and strengthen its defenses. Early's invasion caused considerable panic in both Washington and Baltimore, and his forces reached Silver Spring, Maryland, and the outskirts of the District of Columbia. He also sent some cavalry under Brig. Gen. John McCausland to Washington's western side.

Knowing that he lacked sufficient strength to capture the federal capital, Early led skirmishes at Fort Stevens and Fort DeRussy. Opposing artillery batteries also traded fire on July 11 and July 12. On both days, President Abraham Lincoln watched the fighting from the parapet at Fort Stevens, his lanky frame a clear target for hostile military fire. After Early withdrew, he said to one of his officers, "Major, we haven't taken Washington, but we scared Abe Lincoln like hell."[42]

Early retreated with his men and captured loot across the Potomac River to Leesburg, Virginia, on July 13, then headed west toward the Shenandoah Valley. At the Second Battle of Kernstown on July 24, 1864, Early's forces defeated a Union army under Brig. Gen. George Crook. Through early August, Early's cavalry and guerrilla forces also attacked the B&O Railroad in various places, seeking to disrupt Union supply lines, as well as secure supplies for their own use.

As July ended, Early ordered cavalry under Generals McCausland and Bradley Tyler Johnson to raid across the Potomac River. On July 30, they burned more than 500 buildings in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, nominally in retaliation for Union Maj. Gen. David Hunter's burning VMI in June and the homes of three prominent Southern sympathizers in Jefferson County, West Virginia, earlier that month, as well as the Pennsylvania town's failure to heed his ransom demands (town leaders collecting door to door could only raise about $28,000 of the $100,000 in gold or $500,000 in greenbacks demanded, the local bank having sent its reserves out of town in anticipation).[43][41] Early's forces also burned the region's only bridge across the Susquehanna River, impeding commerce as well as Union troop movements. Union cavalry commander Brig. Gen. William W. Averell had thought the attackers would raid toward Baltimore, Maryland, and so arrived too late to save Chambersburg. However, a rift developed between Early's two cavalry commanders because Marylander Johnson was loath to raze Cumberland and Hancock for likewise failing to meet ransom demands, because he saw McCausland's brigade commit war crimes while looting Chambersburg ("every crime ... of infamy.. except murder and rape").[44] Averill's Union cavalry, although half the size of the Confederate cavalry, chased them back across the Potomac River, and they skirmished three times, the Confederate cavalry losing most severely at the Battle of Moorefield in Hardy County, West Virginia, on August 7.

Realizing Early could still easily attack Washington, Grant in mid-August sent Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan and additional troops to subdue Early's forces, as well as local guerilla forces led by Col. John S. Mosby. At times outnumbering the Confederates three to one, Sheridan defeated Early in three battles. Sheridan's troops also laid waste to much of what had been the Confederacy's breadbasket, in order to deny rations and other supplies to Lee's army. On September 19, 1864, Early's troops lost the Third Battle of Winchester after raiding the B&O depot at Martinsburg, West Virginia. Key subordinates (General Robert Rodes and A.C. Godwin) were killed, General Fitz Lee wounded and General John C. Breckinridge was ordered back to Southwest Virginia—so Early had lost about 40% of his troop strength since the campaign began, despite distracting thousands of Union troops.[45] The Confederates never again captured Winchester or the northern Valley. On September 21–22, Early's troops lost Strasburg after Sheridan's much larger force (35,000 Union troops vs. 9500 Confederates ) won the Battle of Fisher's Hill, capturing much of Early's artillery and 1,000 men, as well as inflicting about 1,235 casualties including the popular Sandie Pendleton. In a surprise attack the following month, on October 19, 1864, Early's Confederates initially routed two thirds of the Union army at the Battle of Cedar Creek. In his post-battle dispatch to Lee, Early noted that his troops were hungry and exhausted and claimed they broke ranks to pillage the Union camp, which allowed Sheridan critical time to rally his demoralized troops and turn their morning defeat into an afternoon victory. However, he privately conceded he had hesitated rather than pursue the advantage, and another key subordinate, Dodson Ramseur, was wounded, captured and died the next day despite the best efforts of Union and Confederate surgeons.[46] Furthermore, one of Early's key subordinates, Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon, in his memoirs written in 1908 (after the irascible Early's death), also blamed Early's indecision rather than the troops for the afternoon rout.[47]

Although distracting thousands of Union troops from the action around Petersburg and Richmond for months, Early had also lost the confidence of former Virginia governor Extra Billy Smith, who told Lee that troops no longer considered Early "a safe commander."[48] Lee ordered most of the remaining Second Corps to rejoin the Army of Northern Virginia defending Petersburg by late November, leaving Early to defend the entire Valley with a brigade of infantry and some cavalry under Lunsford L. Lomax.[49] When Sheridan's troops nearly destroyed the Confederates at Waynesboro on March 2, 1865, Early could not evacuate his men (many of whom were captured), nor artillery and supplies. He barely escaped capture with his cousin Peter Hairston and a few members of his staff, returning almost alone to Petersburg. Hairston returned to one of his plantations near Danville, Virginia, where Confederate President Jefferson Davis fled to stay with slave trader and financier William Sutherlin.[50]

Lee, however, would not put Early back in command of the Second Corps there because his former subordinate Gordon was handling matters satisfactorily, and the press and other commanders suggested the recent disasters made Early unacceptable to the troops.[51] Lee told Early to go home and wait, then relieved Early of his command on March 30, writing:

While my own confidence in your ability, zeal, and devotion to the cause is unimpaired, I have nevertheless felt that I could not oppose what seems to be the current of opinion, without injustice to your reputation and injury to the service. I therefore felt constrained to endeavor to find a commander who would be more likely to develop the strength and resources of the country, and inspire the soldiers with confidence. ... [Thank you] for the fidelity and energy with which you have always supported my efforts, and for the courage and devotion you have ever manifested in the service ...

— Robert E. Lee, letter to Early

Thus ended Early's Confederate career.

Postbellum career

When the Army of Northern Virginia surrendered on April 9, 1865, Early escaped to Texas on horseback, hoping to find a Confederate force that had not surrendered. He proceeded to Mexico, and from there sailed to Cuba and finally reached (the then Province of) Canada. Despite his former Unionist stance, Early declared himself unable to live under the same government as the Yankee.[16] While living in Toronto with some financial support from his father and elder brother, Early wrote A Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence, in the Confederate States of America (1866), which focused on his Valley Campaign.[52] The book became the first published by a major general about the war.[16] Early spent the rest of his life defending his actions during the war and became among the most vocal in justifying the Confederate cause, fostering what became known as the Lost Cause movement.

President Andrew Johnson pardoned Early and many other prominent Confederates in 1869, but Early took pride in remaining an "unreconstructed rebel", and thereafter wore only suits of "Confederate gray" cloth. He returned to Lynchburg, Virginia, and resumed his legal practice about a year before the 1870 death of General Robert E. Lee. However, Early's father died in 1870, and the mother of his four children (whom he had never married) married another man in 1871. Early spent the rest of his life in "illness and squalor so severe that it reduced him to continual begging from family and friends."[53] In an 1872 speech on the anniversary of General Lee's death, Early claimed inspiration from two letters Lee had sent him in 1865.[54] In Lee's published farewell order to the Army of Northern Virginia, the general had noted the "overwhelming resources and numbers" that the Confederate army had fought against. In one letter to Early, Lee requested information about enemy strengths from May 1864 to April 1865, the war's last year, in which his army fought against Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant (the Overland Campaign and the Siege of Petersburg). Lee wrote, "My only object is to transmit, if possible, the truth to posterity, and do justice to our brave Soldiers."[55] Lee also wrote, "I have not thought proper to notice, or even to correct misrepresentations of my words & acts. We shall have to be patient, & suffer for awhile at least. ... At present the public mind is not prepared to receive the truth."[55]

In his final years, Early became an outspoken proponent of white supremacy, which he believed was justified by his religion; he despised abolitionists. In the preface to his memoirs, Early characterized former slaves as "barbarous natives of Africa" and considered them "in a civilized and Christianized condition" as a result of their enslavement. He continued:

The Creator of the Universe had stamped them, indelibly, with a different color and an inferior physical and mental organization. He had not done this from mere caprice or whim, but for wise purposes. An amalgamation of the races was in contravention of His designs or He would not have made them so different. This immense number of people could not have been transported back to the wilds from which their ancestors were taken, or, if they could have been, it would have resulted in their relapse into barbarism. Reason, common sense, true humanity to the black, as well as the safety of the white race, required that the inferior race should be kept in a state of subordination. The conditions of domestic slavery, as it existed in the South, had not only resulted in a great improvement in the moral and physical condition of the negro race, but had furnished a class of laborers as happy and contented as any in the world.[56]

Despite Lee's avowed desire for reconciliation with his former West Point colleagues who remained with the Union and with Northerners more generally, Early became an outspoken and vehement critic of Lieutenant General James Longstreet and particularly criticized his actions at the Battle of Gettysburg and also took issue with him and other former Confederates who after the war worked with Republicans and African Americans. Early also often criticized former Union General (later President) Ulysses S. Grant as a "butcher."

In 1873, Early was elected president of the Southern Historical Society, an association he continued until his death. He frequently contributed to the Southern Historical Society Papers, whose secretary was former Confederate chaplain J. William Jones. With the support of former Confederate General William N. Pendleton, who like Jones ministered in Lexington, Virginia, after the war, Early also became the first president of the Lee Monument Association, and of the Association of the Army of Northern Virginia. Beginning around 1877, Early and former Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard supported themselves in part as officials of the (reputedly then corrupt) Louisiana Lottery.[57] Early also corresponded with and visited former Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who retired to Mississippi's Gulf Coast near New Orleans, Louisiana, to write his own memoirs. Former Confederate First Lady Varina Davis, while also furthering the Lost Cause and corresponding with Early, characterized Early as a "crabby bachelor with a squeaky, high-pitched voice".[58]

Death and legacy

Early tripped and fell down granite stairs at the Lynchburg, Virginia, post office on February 15, 1894. A medical examination found no broken nor fractured bones, but noted Early suffered from back pain and mental confusion. He failed to recover during the next few weeks and died quietly at home on March 2, holding the hand of U.S. Sen. John Warwick Daniel. Local obituaries speculated a net worth at $200,000 to $300,000.[59] His doctor did not specify an exact cause on the death certificate.[60] Virginia's flag flew at half-staff over the Capitol the afternoon of the funeral, and cannons boomed 36 times at five minute intervals. A procession of VMI cadets, 300 Confederate veterans and local militia accompanied the flag-draped casket and riderless horse with reversed stirrups to St. Paul's Church. During the brief service, Rev. T. M. Carson, a veteran of Early's Valley Campaign, testified as to "the almost countless forces of the enemy."[61] Another, simple service, taps and a farewell kiss by one of Early's "noblest and bravest followers" concluded with Early's burial at Spring Hill Cemetery in Lynchburg.[61] Nearby lay (distant) family members Captain Robert D. Early (killed in the Battle of the Wilderness, May 5, 1864) and his brother William (killed at the Battle of Five Forks, April 1, 1865) and their parents, as well as Confederate generals Thomas T. Munford and James Dearing.[62]

The Library of Congress has some of his papers.[63] The Virginia Historical Society holds some of his papers, along with other members of the Early family.[64] The Library of Virginia and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have Hairston family papers, but they barely mention activities during the American Civil War, other than selling provisions to the Confederacy.[5]

The Lost Cause that Early promoted and espoused was continued by memorial associations such as the United Confederate Veterans (founded 1889) and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (founded 1894), as well as by his niece Ruth Hairston Early.[8] Jubal Early's book Autobiographical Sketch and Narrative of the War between the States, was published posthumously in 1912.[65] His book The Heritage of the South: a history of the introduction of slavery; its establishment from colonial times and final effect upon the politics of the United States, was published posthumously in 1915.[66] Historians, including Douglas Southall Freeman (who grew up in Lynchburg near the former Early home and remembered relatives' pointing out the stooped and grumbling Early as a bogeyman-type warning), espoused the Lost Cause to greater or lesser degrees until the 1960s, arguing the concept helped Southerners to cope with the dramatic social, political, and economic changes in the postbellum era, including Reconstruction.[67] Early's biographer, Gary Gallagher, noted that Early understood the struggle to control public memory of the war, and that he "worked hard to help shape that memory, and ultimately enjoyed more success than he probably imagined possible."[68] Other modern historians such as sociologist James Loewen, author of The Truth About Columbus, believed Early's views fomented racial hatred.[69]

Honors

- The last ferry operating on the Potomac River was named General Jubal A. Early.[70] Early's name was removed in 2020,[71] and it is now called Historic White's Ferry.

- A major thoroughfare in Winchester, Virginia, is named "Jubal Early Drive" in his honor.

- Virginia Route 116 from Roanoke City to Virginia Route 122 in Franklin County is named after him, the "Jubal Early Highway," and passes his birthplace, as identified by a historical highway marker. In Roanoke County, it is referred to as "JAE Valley Road," incorporating Jubal Anderson Early's initials.

- His childhood home, the Jubal A. Early House, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1997[72] and maintained in part by a private foundation[73]

- Fort Early and Jubal Early Monument can be found in Lynchburg, Virginia.

Streets named after him

- Jubal Early Drive, Forest, Virginia

- Jubal Early Highway, Boones Mill, Virginia

- East Jubal Early Drive, Winchester, Virginia

- West Jubal Early Drive, Winchester, Virginia

- Jubal Early Lane, Conroe, Texas

- Jubal Early Drive, Fredericksburg, Virginia

- Jubal Early Drive, Petersburg, West Virginia

- Early Street, Lynchburg, Virginia

- Jubal Early Road, Zephyrhills, Florida

- Early Dr. on USAG Fort A. P. Hill

- North Early Street, Alexandria, Virginia – in 2023, local legislators have proposed renaming the street.[74][75]

- General Early Drive, Suffolk, Virginia

- General Early Drive, Harpers Ferry, West Virginia

- Early Place, Greensboro, Georgia

In popular culture

- Early is portrayed by MacIntyre Dixon in the 1993 film Gettysburg, based on Michael Shaara's novel, The Killer Angels. His scenes appear only in the Director's Cut release.

- The bounty hunter in "Objects in Space", the final episode of Joss Whedon's series Firefly, is named Jubal Early because Joss Whedon was told that Early was an ancestor of Nathan Fillion, who played the main character Malcolm Reynolds. The character is played by Richard Brooks.

- In the Jean-Claude Van Damme film Inferno, a main character played by Pat Morita is named Jubal Early.

- Jubal Early is mentioned in The Waltons episode "The Conflict", as a General of Henry Walton, Zebulon Walton's elder brother by his (90 year old at time of telling) widow Martha Corinne Walton while reminiscing about her late husband to the family in 1936.

- Early is a character in a number of alternate history novels, including Harry Turtledove's The Guns of the South and Robert Conroy's The Day After Gettysburg.

See also

References

- ^ John Y. Simon; Michael E. Stevens (2003). New Perspectives on the Civil War: Myths and Realities of the National Conflict. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-4616-1052-6.

- ^ J. Tracy Power, "Jubal A. Early (1816–1894)" Archived November 26, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "James-T-Eddins – User Trees". www.genealogy.com. Archived from the original on November 26, 2022.

- ^ "Hairston Plantations | African American Historic Sites Database". Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ^ a b "Wilson and Hairston Family Papers, 1751–1928".

- ^ Henry Wiencek, The Hairstons: an American Family in Black and White (Macmillan, 2000) p. 8

- ^ 1830 U.S. Federal Census for Franklin county, Southwest section shows Jubal Early as owning 7 enslaved persons. The same census names five Early households; the others were headed by his father Joab Early, as well as Henry Early, Lamarck Early and Melchizidek Early.

- ^ a b "Dictionary of Virginia Biography – Ruth Hairston Early Biography".

- ^ Benjamin Franklin Cooling III, Jubal Early: Robert E. Lee's "Bad Old Man" (Rowman and Littlefield, 2014) p. 2

- ^ Early, Ruth Hairston. The Family of Early: Which Settled Upon the Eastern Shore of Virginia and Its Connection with Other Families, Brown-Morrison, 1920, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Resignation of Lewis A. Armistead, January 1836, RG 77, E18, National Archives. Some historians characterize Armistead's departure as a dismissal from the Academy; see citations in Lewis Addison Armistead.

- ^ Cooling pp. 2–3

- ^ Cooling p. 4

- ^ Cynthia Miller Leonard, Virginia General Assembly 1619–1978 (Richmond: Virginia State Library 1978) p. 400

- ^ Catalogue of Officers and Alumni of Washington & Lee University, p. 75, available at https://books.google.com/books?id=SS_PAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA75&lpg Archived November 26, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f Power, J. Tracy. "Jubal A. Early (1816–1894)". Encyclopedia Virginia.

- ^ Cooling pp. 4–5

- ^ "John Francis Hamtramck – Historic Shepherdstown".

- ^ Cooling pp. 6–7

- ^ 1850 U.S. Federal Census for Franklin County, dwelling no. 5; 1860 U.S. Federal Census for Franklin County, South Western district, dwelling 157. Likewise in the 1880 census, he lived in a boardinghouse. All such censuses are available at libraries on ancestry.com

- ^ Cooling pp. 7–8

- ^ Leonard p. 475

- ^ According to Wiencek p. 144, Jack Hairston died early in the war, despite being his parents' only son and easily capable of hiring a substitute, and his cousin who tried to locate his body also died of disease contracted during the search.

- ^ Wiencek, p. 148

- ^ "Fisher, Charles Frederick | NCpedia".

- ^ Douglas Southall Freeman, Lee's Lieutenants (abridged 1-volume version edited by Stephen W. Sears) (Scribner 1998) p. 83

- ^ Gallagher, Struggle for the Shenandoah, p. 21.

- ^ Wiencek pp. 149–150

- ^ Freeman, Lee's Lieutenants, p. 252

- ^ Freeman at pp. 494–504

- ^ Douglas R. Egerton, The Wars of Reconstruction (Bloomsbury Press 2014) p. 212

- ^ David G. Smith, "The Capture of African Americans during the Gettysburg Campaign," in Virginia's Civil War, ed. Peter Wallenstein and Betram Wyatt-Brown (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2005), 137–151.

- ^ O.R., Series I, Vol. LI, Part II, pp. 973–974

- ^ O.R., Series I, Vol. XXXVI, Part III, pp. 873–874

- ^ Freeman pp. 726–727, 739

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ O.R., Series I, Vol. XLIII, Part 1, p. 1020.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ NRIS p. 16 available at http://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/stagsere/se1/se5/010000/010400/010482/pdf/msa_se5_10482.pdf Archived February 23, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Loewen, James W. (July 1, 2015). "Why do people believe myths about the Confederacy? Because our textbooks and monuments are wrong. False history marginalizes African Americans and makes us all dumber". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C.: Graham Holdings Company.

Confederate cavalry leader Jubal Early demanded and got $300,000 from them lest he burn their town, a sum equal to at least $5,000,000 today.

- ^ a b Explore PA History Archived February 7, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Freeman, p. 742.

- ^ "Jubal Early's grave in Lynchburg, Virginia". September 17, 2014.

- ^ Freeman p. 745

- ^ Freeman p. 749

- ^ Freeman pp. 758–761

- ^ Gordon, pp. 352–372.

- ^ Freeman p. 751

- ^ Freeman p. 765

- ^ Wiencek, p. 164

- ^ Freeman pp. 768–69

- ^ "A memoir of the last year of the War of Independence, in the Confederate States of America". Toronto, Printed by Lovell & Gibson. 1866.

- ^ Kathryn Shively Meier, "Jubal A. Early: Model Civil War Sufferer", J19: The Journal of Nineteenth-Century Americanists, Volume 4, Number 1, Spring 2016, pp. 206–214

- ^ Gary W. Gallagher, The Confederate War (Harvard University Press 1997) pp. 168–169

- ^ a b Gallagher & Nolan, p. 12.

- ^ Early and Gallagher, pp. xxv–xxvi.

- ^ Weincek p. 284

- ^ Joan E. Cashin, First Lady of the Confederacy: Varina Davis' Civil War (Harvard University Press 2006) p. 254

- ^ Cooling p. 142

- ^ "Medical Histories of Confederate Generals", Jack D. Welsh, M.D., 1999

- ^ a b Cooling p. 143

- ^ "Spring Hill Cemetery". Archived from the original on February 8, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- ^ Jubal Anderson Early: A Register of His Papers in the Library of Congress Archived November 26, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. Prepared by Marilyn K. Parr and David Mathisen. Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., 2008.

- ^ "Early Family Papers - Ezell Family Papers". Virginia Museum of History & Culture.

- ^ available at http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0015 Archived November 26, 2022, at the Wayback Machine and http://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/early/early.html Archived April 20, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ available at https://archive.org/details/heritageofsouth01earl

- ^ Ulbrich, p. 1222.

- ^ Quoted in https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Early_Jubal_A_1816-1894#start_entry Archived February 8, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ James W. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me

- ^ "White's Ferry website". Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ "A Confederate statue is toppled in rural Maryland, then quietly stored away". The Washington Post. July 4, 2020.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "General Jubal Early Homeplace Preservation". Archived from the original on August 14, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2004.

- ^ "Alexandria proposes replacing Confederate street names". NBC Washington. October 13, 2023. Archived from the original on October 14, 2023. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ^ Miles, Vernon (May 18, 2023). "Office of Historic Alexandria provides guide to city's Confederate street names ahead of renaming". ALXnow. Archived from the original on October 14, 2023. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

Further reading

- Bruns, James H. (2021). Crosshairs on the Capital: Jubal Early's Raid on Washington D.C., July 1864 – Reasons, Reactions, and Results. Casemate.

- Cooling, Benjamin Franklin, III. Jubal Early: Robert E. Lee's Bad Old Man. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2014.

- Early, Jubal A. A Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence in the Confederate States of America. Edited by Gary W. Gallagher. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2001. ISBN 1-57003-450-8.

- Early, Jubal A. The Campaigns of Gen. Robert E. Lee: An Address by Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early before Washington & Lee University, January 19, 1872. Baltimore: John Murphy & Co., 1872 OCLC 44086028.

- Early, Jubal A., and Ruth H. Early. Lieutenant General Jubal Anderson Early, C.S.A.: Autobiographical Sketch and Narrative of the War Between the States. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1912. OCLC 1370161.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Freeman, Douglas S. R. E. Lee, A Biography. 4 vols. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1934–35. OCLC 166632575.

- Gallagher, Gary W. Jubal A. Early, the Lost Cause, and Civil War History: A Persistent Legacy (Frank L. Klement Lectures, No. 4). Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-87462-328-6.

- Gallagher, Gary W., ed. Struggle for the Shenandoah: Essays on the 1864 Valley Campaign. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-87338-429-6.

- Gallagher, Gary W., and Alan T. Nolan, eds. The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-253-33822-0.

- Gordon, John B. Reminiscences of the Civil War. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1904.

- Leepson, Marc. Desperate Engagement: How a Little-Known Civil War Battle Saved Washington D.C., and Changed American History. New York: Thomas Dunne Books (St. Martin's Press), 2005. ISBN 978-0-312-38223-0.

- Lewis, Thomas A., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. The Shenandoah in Flames: The Valley Campaign of 1864. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1987. ISBN 0-8094-4784-3.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Tagg, Larry. The Generals of Gettysburg. Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- Ulbrich, David. "Lost Cause." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- U.S. War Department. The War of the Rebellion Archived September 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.