Henry Johnson (World War I soldier)

Henry Johnson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | William Henry Johnson |

| Nickname(s) | Black Death |

| Born | c. July 15, 1892[1] Winston-Salem, North Carolina, United States |

| Died | July 1, 1929 (aged 36) Washington, D.C., United States |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1917–1919 |

| Rank | Sergeant |

| Service number | 1316046 |

| Unit | 369th Infantry Regiment, New York National Guard |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

| Awards | |

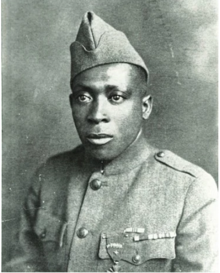

William Henry Johnson (circa July 15, 1892 – July 1, 1929), commonly known as Henry Johnson,[2] was a United States Army soldier who performed heroically in the first African American unit of the United States Army to engage in combat in World War I.[3] On watch in the Argonne Forest on May 14, 1918, he fought off a German raid in hand-to-hand combat, killing multiple German soldiers and rescuing a fellow soldier while suffering 21 wounds, in an action that was brought to the nation's attention by coverage in the New York World and The Saturday Evening Post later that year. On June 2, 2015, he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor by President Barack Obama in a ceremony at the White House.[4]

In 1918, the French awarded Johnson with a Croix de guerre with star and bronze palm. He was the first U.S. soldier in World War I to receive that honor.[3][5]

Johnson died poor and in obscurity in 1929.[1] There was a long struggle to achieve awards for him from the U.S. military. He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart in 1996. In 2002, the U.S. military awarded him the Distinguished Service Cross. Previous efforts to secure the Medal of Honor failed,[3] but in 2015 he was posthumously honored with the award. On May 24, 2022, The Naming Commission recommended that Fort Polk in Leesville, Louisiana, be renamed Fort Johnson after Henry Johnson, rather than its previous namesake, Confederate General Leonidas Polk. The post was renamed in Johnson's honor in a ceremony on June 5, 2023.

Early life and education

Johnson stated that he was born in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, on July 15, 1892, when registered for the World War I draft, but he used other dates on other documents and may not have known the exact date of his birth.[1][6][7] He moved to Albany, New York when he was in his early teens and worked various jobs, such as a chauffeur, soda mixer, and as a redcap porter at the Albany Union Station on Broadway.[1][7]

Military career

Henry Johnson enlisted in the United States Armed Forces on June 5, 1917 as a 5-foot-4-inch young man. This was almost two months after the American entry into World War I, joining the all-black New York National Guard 15th Infantry Regiment, which, when mustered into Federal service, was redesignated as the 369th Infantry Regiment, and was then based in Harlem. The 369th Infantry joined the 185th Infantry Brigade upon arrival in France, but was relegated to labor service duties instead of combat training. The 185th Infantry Brigade was in turn assigned on January 5, 1918, to the 93rd Infantry Division.

Although General John J. Pershing, Commander-in-Chief of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) on the Western Front, wished to keep the American forces autonomous, he "loaned" the 369th to the 161st Division of the French Army. Supposedly, the unreported and unofficial reason he was willing to detach the African-American regiments from U.S. command was that vocal white U.S. soldiers refused to fight alongside black troops. These black regiments suffered considerable harassment by white U.S. soldiers and even denigration by the AEF headquarters, which went so far as to release the notorious pamphlet Secret Information Concerning Black American Troops, which "warned" French civilian authorities of the alleged inferior nature and supposed tendencies of African-American troops to commit sexual assaults.[3] Johnson arrived in France on New Year's Day, 1918.

The French Army needed more men and welcomed the reinforcements.[8] The 369th Infantry regiment, later nicknamed the "Harlem Hellfighters", was among the first to arrive in France, and among the most highly decorated when it returned. The 369th was an all-black unit under the command of mostly white officers, including their commander, Colonel William Hayward. The idea of a black New York National Guard regiment had first been put forward by Charles W. Fillmore, a black New Yorker. Governor Charles Seymour Whitman, inspired by the brave showing of the black 10th Cavalry in Mexico, authorized the project. He appointed Colonel Hayward to carry out the task of organizing the unit, and Hayward gave Fillmore a commission as a captain in the 15th Infantry Regiment, New York National Guard. The 15th New York Infantry Regiment became the 369th United States Infantry Regiment prior to engaging in combat in France.

The 369th got off to a rocky departure from the United States, making three attempts over a period of months to sail for France before finally getting out of sight of land. Even then, their transport, which had stopped and anchored before it could get out of the harbor due to a sudden snowstorm, was struck by another ship due to poor visibility. The captain of the transport, the Pocahontas, wanted to turn back, much to the dismay of his passengers. The by-now angry and impatient members of the 369th, led by Hayward, took a very dim view of any further delay. Since damage to the ship was well above the waterline, the ship's captain admitted that there was no danger of sinking. Hayward then informed the captain that he saw no reason to turn back, aside from cowardice. Hayward's men repaired the damage themselves and the ship sailed on. According to Hayward's notes, they "landed at Brest. Right side up" on December 27, 1917. They acquitted themselves well once they finally got to France. Many months were to pass by, however, before they were to see combat.

The French Army assigned Johnson's regiment to Outpost 20 on the edge of the Argonne Forest in the Champagne region of France, equipping it with French rifles and helmets.[9] While on observation post duty on the night of May 14, 1918, Johnson came under attack by a large German raiding party, which may have numbered up to 36 soldiers. Using grenades, the butt of his rifle, a bolo knife and his bare fists, Johnson repelled the Germans, killing four while wounding others, rescuing Needham Roberts from capture and saving the lives of his fellow soldiers. Johnson suffered 21 wounds during the ordeal.[3][9] This act of valor earned him the nickname of "Black Death", as a sign of respect for his prowess in combat.

The story of Johnson's exploits first came to national attention in an article by Irvin S. Cobb entitled "Young Black Joe" published in the August 24, 1918 Saturday Evening Post.[10]

Returning home, now-Sergeant Johnson participated (with his regiment) in a victory parade on Fifth Avenue in New York City in February 1919.[9] Johnson was then paid to take part in a series of lecture tours. He appeared one evening in St. Louis, and instead of delivering the expected tale of racial harmony in the trenches, revealed the abuse that black soldiers had suffered, such as white soldiers refusing to share trenches with blacks. Soon afterwards, a warrant was issued for Johnson's arrest for violating the regulations governing wearing his uniform (beyond the prescribed date of his commission). Paid lecturing engagements dried up.[11]

Military awards

The French government awarded Johnson the Croix de guerre with a special citation and a golden palm.[3] He was the first American soldier to receive the award.[3][12]

In June 1996, Johnson was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart by President Bill Clinton. In February 2003, the Distinguished Service Cross, the Army's second highest award, was awarded to Johnson.[13] John Howe, a Vietnam War veteran who had campaigned tirelessly for recognition for Johnson, and U.S. Army Major General Nathaniel James, President of the 369th Veterans' Association, were present at the ceremony in Albany.[14] The award was received by Herman A. Johnson, one of the Tuskegee Airmen of WWII, on behalf of Henry Johnson, then believed to be his father; the mistake was not clarified until 2015, a decade after the younger Johnson's death, as part of the further research done leading up to the senior Johnson's Medal of Honor.[15]

Medal of Honor

On May 14, 2015, the White House announced that Johnson would receive the Medal of Honor posthumously, presented by President Barack Obama.[16] In the ceremony, held on 2 June 2015, Johnson's medal was received on his behalf by Command Sergeant Major Louis Wilson of the New York National Guard. Obama said, "The least we can do is to say, 'We know who you are. We know what you did for us. We are forever grateful.'"[17]

The official citation reads:[18]

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, March 3, 1863, has awarded in the name of Congress the Medal of Honor to

Private Henry Johnson

United States Army

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty:

Private Johnson distinguished himself by acts of gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty while serving as a member of Company C, 369th Infantry Regiment, 93rd Division, American Expeditionary Forces, during combat operations against the enemy on the front lines of the Western Front in France on May 15, 1918. Private Johnson and another soldier were on sentry duty at a forward outpost when they received a surprise attack from a German raiding party consisting of at least 12 soldiers. While under intense enemy fire and despite receiving significant wounds, Private Johnson mounted a brave retaliation, resulting in several enemy casualties. When his fellow soldier was badly wounded, Private Johnson prevented him from being taken prisoner by German forces. Private Johnson exposed himself to grave danger by advancing from his position to engage an enemy soldier in hand-to-hand combat. Wielding only a knife and gravely wounded himself, Private Johnson continued fighting and took his Bolo knife and stabbed it through an enemy soldier's head. Displaying great courage, Private Johnson held back the enemy force until they retreated. Private Johnson's extraordinary heroism and selflessness above and beyond the call of duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit and the United States Army.

Later life and death

Veterans Bureau records show that a "permanent and total disability" rating was granted to Johnson on September 16, 1927, as a result of his tuberculosis infection. Additionally, Johnson suffered approximately 21 different combat injuries, rendering him unable to return to his previous job as a porter. Also, Veterans Bureau records refer to Johnson receiving monthly compensation and regular visits by Veterans Bureau medical personnel until his death.[19]

Johnson died on July 1, 1929, in Washington, D.C., of myocarditis.[20] He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery on July 6, 1929.

Legacy

In 1919, co-founder of the American Legion Theodore Roosevelt Jr., son of former United States President Theodore Roosevelt, referred to Johnson as one of the "five bravest Americans" to have served in World War I.[9]

Interest in obtaining fitting recognition for Johnson grew during the 1970s and 1980s. In November 1991, a monument was erected in Albany, New York's Washington Park in his honor, and a section of Northern Boulevard was renamed Henry Johnson Boulevard.

In December 2004, the Postal facility at 747 Broadway was renamed the "United States Postal Service Henry Johnson Annex".

On September 4, 2007, the Brighter Choice Foundation in Albany, New York, dedicated the Henry Johnson Charter School, with Johnson's granddaughter in attendance.

A 1918 commercial poster honoring Johnson's wartime heroics was the subject of a 2012 episode of the PBS television series History Detectives.[21]

As of December 3, 2014, the national defense bill included a provision, added by Senator Chuck Schumer, to award Johnson the Medal of Honor.[22]

For many years, it was thought that Herman Archibald Johnson was the son of Henry Johnson. In tracking Henry Johnson's genealogy prior to his being awarded the Medal of Honor, however, it was discovered that there was no family connection.[6][15] The Army was quoted as saying, "While we appreciate the Johnson family fighting for the award and keeping the memory and valorous acts of Henry Johnson alive, we regretfully cannot recognize them as PNOK," or primary next of kin.[19]

In December 2014, the City School District of Albany established a Junior Reserve officers' Training Program (JROTC) at Albany High School named the Henry Johnson Battalion in honor of him.[23] The program currently enrolls over 100 cadets.

In 2017, Albany-area PBS station WMHT aired a documentary about Henry Johnson entitled Henry Johnson: A Tale of Courage.[24]

Johnson's story is recounted in the song Don't Tread on Me (Harlem Hellfighters) by the Ukrainian death metal band 1914 on their album Where Fear and Weapons Meet, released October 22, 2021.[25]

In June 2023, Fort Polk in Louisiana, a U.S. Army base, was renamed for Johnson.[26]

References

- ^ a b c d "Sergeant Henry Johnson". US Army. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ Although he has been confused with Henry Lincoln Johnson in several sources, they are different individuals. See Smolenyak, Megan. "Memorial Day: Correcting the Story of World War I Medal of Honor Recipient Sgt. Henry Johnson". Huffington Post. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Martin, Tony (2008). "Johnson, Henry". American National Biography Online.

- ^ "Two World War I Soldiers Posthumously Receive Medal of Honor". The New York Times. June 3, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- ^ "Conflicts – World War I – Personal Stories: Henry Johnson, 15th New York Infantry — The Harlem Hellfighters (1891—1929)". New York State Museum. Archived from the original on March 4, 2011.

- ^ a b Clayton, Cindy. "Genealogist helps set the record straight". Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ^ a b "Henry Johnson in the World War I draft registration". Albany, New York. June 5, 1917. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- ^ Trouillard, Stéphanie (May 14, 2018). "Henry Johnson, Harlem soldier and forgotten WWI hero". France24. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c d King, Gilbert. "Remembering Henry Johnson, the Soldier Called "Black Death"". Smithsonian magazine.

- ^ Cobb, Irvin S. (1918). "Chapter XVII. Young Black Joe". The Glory of the Coming. New York City: George H. Doran Company. Retrieved August 10, 2014 – via Gutenberg.org.

- ^ Grant, Colin (2008). Negro with a Hat, The Rise and Fall of Marcus Garvey and his Dream of Mother Africa. London, UK: Jonathan Cape. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-224-07868-9.

- ^ Report on the Activities in the World War of 369th United States Infantry (15th New York) (PDF). Headquarters Division, New York Guard. July 1, 1920. Located in the George S. Robb papers at the Kansas Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas.

- ^ Headquarters, Department of the Army (November 18, 2005). "General Orders No. 9" (PDF). Army Publishing Directorate.

- ^ Triggs, Marcia (2003). "Black WWI hero receives due honors". U.S. Department of Defense.

- ^ a b Lamothe, Dan (June 2, 2015). "Army discovers sad surprise in family history of new Medal of Honor recipient Henry Johnson". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. ISSN 0190-8286. OCLC 1330888409.

- ^ "White House: WWI vet Henry Johnson to receive Medal of Honor". Times Union. May 14, 2015.

- ^ Shear, Michael (June 2, 2015). "Two World War I Soldiers Posthumously Receive Medal of Honor". The New York Times. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ^ "Sergeant Henry Johnson". US Army. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Lamothe, Dan (June 11, 2015). "How the White House and media got it wrong on Medal of Honor recipient Henry Johnson". Washington Post. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ^ Smolenyak, Megan. "WWI Hero Sgt. Henry Johnson Receives Long Overdue Medal of Honor". The Huffington Post. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ Tukufu, Zuberi. "Our Colored Heroes – History Detectives – PBS". PBS. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ Grondahl, Paul (December 3, 2014). "WWI hero Henry Johnson on verge of Medal of Honor". Times Union. Retrieved December 3, 2014.

- ^ "Congressman promotes JROTC cadets". City School District of Albany. Archived from the original on December 29, 2016.

- ^ "Henry Johnson: A Tale of Courage". WMHT.

- ^ "1914 - "Where Fear and Weapons Meet"". Everything Is Noise. October 21, 2021.

- ^ Iyer, Kaanita (June 13, 2023). "Fort Polk is now Fort Johnson after US Army moves to honor World War I hero | CNN Politics". CNN. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

Further reading

- Sweeney, William Allison (2008). History of the American Negro in the Great World War. LaVergne, TN: BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-0-559-13514-9. OCLC 680498774.

- Williams, Chad Louis (2010). Torchbearers of democracy : African American soldiers and the era of the First World War. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3394-0. OCLC 984707088.

External links

- "Burial Detail: Johnson, Henry". Arlington National Cemetery.

- Bowman, Tom (June 2, 2015). "Obama To Honor Harlem Hellfighter With Medal of Honor". NPR.

- "The Heroics of Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts". Old Magazine Articles.

- Rossen, Jake (August 29, 2019). "Henry Johnson, the One-Man Army Who Fought Off Dozens of German Soldiers During World War I". Mental Floss.