Frances Clayton

Frances Louisa Clayton (c. 1830 – after 1863), also recorded as Frances Clalin, was an American woman who purportedly disguised herself as a man to fight for the Union Army in the American Civil War, though many historians now believe her story was likely fabricated. Under the alias Jack Williams, she claimed to have enlisted in a Missouri regiment along with her husband, and fought in several battles. She claimed that she left the army soon after her husband died at Stones River.[1][2]

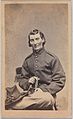

Newspaper reports indicate that Clayton served in both cavalry and artillery units. Her story became known and widely circulated after her service, though each account contains contradictory, and in some cases dubious, information about her life and supposed service. Several photographs of Clayton, including images of her in uniform, are known to exist. However, little else is known of her life and no official military record exists of her service.[3]

Biography

Clayton and her husband were from Minnesota.[4] Her husband's name is not clear; one newspaper story gives it as Frank Clayton, apparently a confusion of Frances' own name, while other sources name him John or Elmer.[5] Following the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, the Claytons decided to enlist in the Union Army, with Frances disguising herself as a man named Jack Williams.[6]

By most accounts, they enlisted in a Missouri unit in Saint Paul, Minnesota,[7] despite being from Minnesota.[6] Clayton is said to have fought in 18 battles.[2] Sources from after the war record her as serving in both cavalry and artillery units, and indicate that she was wounded in battle; according to her subsequent statements this occurred at the Battle of Fort Donelson.[6] The same accounts describe her as a "very tall, masculine looking woman bronzed by exposure".[8] She was further able to convincingly pass as a man through her "masculine stride in walking" and "erect and soldierly carriage", as well as by adopting male vices such as drinking, smoking, chewing tobacco, swearing, and gambling.[9] In the service, she became an "accomplished horse-man" and a "capital swordsman".[10] She was reported to have fought in the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862.[11] In December 1862, she fought in the Battle of Stones River, where her husband was killed during a charge.[12] The news stories reported that she did not stop fighting, and stepped over his body to continue the charge.[6]

Clayton's story only became known after her service and was reported in several newspaper stories, though these accounts all contain contradictory information.[6] According to these stories, Clayton was discharged in Louisville in 1863, shortly after her husband's death. She told reporters that she was never discovered as a woman. Sources say, however, that her discharge resulted from her being medically examined after a bullet wound to the hip.[12] She attempted to return to Minnesota before going back to the military to collect her and her husband's back pay, but her train was ambushed by Confederate guerrillas who took her money and papers. Thereafter, she traveled from Missouri to Minnesota, to Grand Rapids, Michigan, and finally to Quincy, Illinois, where a collection was held to help her on her trip. The last known report describes her heading to Washington, D.C.[6]

Several photographs of Frances Clayton are known to exist. Two were taken in Boston and are now in the possession of the Boston Public Library. One shows Clayton in women's clothing, while the other depicts her in uniform.[12][2][13][14] Unlike other women of the Civil War, Clayton was described by newspapers as tall and masculine-looking. She frequently took part in soldierly past-times such as drinking, smoking, or chewing tobacco.[12]

Legacy and controversy

The series of photos of Clayton, taken in Boston at S. Masury’s studio, has become the most well-known images of a female Civil War soldier. However, the only knowledge of Clayton’s story beyond these photos is her own words as told through a few periodical articles from 1863, primarily the short-lived Philadelphia political pamphlet, "Fincher's Trades' Review." Those stories are fraught with inconsistencies.[15]

Of the units in which she was purported to have served, one did not exist (4th Missouri Heavy Artillery), and the other did not come into existence until after her supposed military service concluded (13th Missouri Cavalry). Neither, of course, was engaged at Stones River, and certainly no cavalry unit participated in a bayonet charge as the story claims.[16] None of the military units in which Clayton claimed to have served contain any record of a Jack Williams, or her husband, or any possible derivation of their names. There are no records in any Missouri or Minnesota unit that match. No Frank (or Elmer, or John) Clayton (or Clalin, or Claylin) was killed at Stones River. The files of the War Department at the National Archives contain no discharge or hospital records.[17] It is possible that Frances Clayton simply fabricated her story and posed in a photographer's prop uniform (to include a non-standard infantry jacket and officer's sword) in an effort profit from the war via donations and a fraudulent pension application.

Clayton and her story served as an inspiration to Beth Gilleland, who produced a 1996 play Civil Ceremony.

Gallery

See also

- List of female American Civil War soldiers

- List of wartime cross-dressers

- Deborah Sampson, impersonated a man to fight during the American War of Independence

References

- ^ Blanton, DeAnne; Cook, Lauren M. (2002). They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War. LSU Press. p. 10. ISBN 0807128066.

- ^ a b c Tsui, Bonnie (2006). She Went to the Field: Women Soldiers of the Civil War. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 66. ISBN 1461748496.

- ^ Blanton, DeAnne; Cook, Lauren M. (2002). They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War. LSU Press. pp. 149–150. ISBN 0807128066.; Record Group 94, Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

- ^ Blanton, DeAnne; Cook, Lauren M. (2002). They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War. LSU Press. p. 150. ISBN 0807128066.

- ^ Pride, Mike (February 21, 2016). "The unbelievable life of Frances Clayton". Concord Monitor. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Blanton, DeAnne; Cook, Lauren M. (2002). They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War. LSU Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 0807128066.

- ^ Tsui, Bonnie (2006). She Went to the Field: Women Soldiers of the Civil War. Guilford, CT: Twodot. p. 66. ISBN 9780762743841.

- ^ Blanton, DeAnne; Cook, Lauren M. (2002). They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War. LSU Press. p. 48. ISBN 0807128066.

- ^ Blanton, DeAnne; Cook, Lauren M. (2002). They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War. LSU Press. pp. 52, 55. ISBN 0807128066.

- ^ Blanton, DeAnne; Cook, Lauren M. (2002). They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War. LSU Press. pp. 55, 58. ISBN 0807128066.

- ^ Hall, Richard H. (2006). Women on the Civil War Battlefront. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. p. 164. ISBN 0700614370.

- ^ a b c d Tsui, Bonnie (2006). She Went to the Field: Women Soldiers of the Civil War. Guilford: Two Dot. p. 66. ISBN 9780762743841.

- ^ "Frances L. Clalin 4 mo. heavy artillery Co. I, 13 mo. Cavalry Co. A. 22 months". Prints & Photographs Online Catalog. Library of Congress. 1865. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ "Miss F. L. Clayton, 4th Mis. Arty [i.e. Missouri Artillery]". Library of Congress. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ Blanton, D., and Lauren Cook, They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War. (Baton Rouge, LSU Press, 2002), 149-150.

- ^ Dyer, Frederick. A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion: Compiled and Arranged from Official Records of the Federal and Confederate Armies, Reports of the Adjutant Generals of the Several States, the Army Registers, and Other Reliable Documents and Sources. (Des Moines, Dyer Publishing Company, 1908).

- ^ Record Group 94, Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

Further reading

- Blanton, DeAnne, and Lauren M. Cook. They Fought Like Demons: Women Soldiers in the American Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8071-2806-6 OCLC 49415925

- Currie, Stephen. Women of the Civil War. San Diego: Lucent Books, 2003. ISBN 1-59018-170-0 OCLC 49529945

- Eggleston, Larry G. Women in the Civil War: Extraordinary Stories of Soldiers, Spies, Nurses, Doctors, Crusaders, and Others. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2003. ISBN 0-7864-1493-6 OCLC 51580671

- Flanagan, Alice K. Great Women of the Union. Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2007. ISBN 0-7565-2035-5 OCLC 226250556

- Frank, Lisa Tendrich. Women in the American Civil War. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, 2008. ISBN 1-85109-600-0 OCLC 152580687

- Funkhouser, Darlene. Women of the Civil War: [Soldiers, Spies, and Nurses]. Wever, IA: Quixote Press, 2004. ISBN 1-57166-258-8 OCLC 61452250

- Hall, Richard. Women on the Civil War Battlefront. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2006. ISBN 0-7006-1437-0 OCLC 62896383

- Kaufman, Will (2004). "No Non-Combatants Here: Women and Civilians in the American Civil War". Women's History Review. 13 (4): 671–678. doi:10.1080/09612020100200406. ISSN 0961-2025. S2CID 162303781.

- Leckie, Robert. None Died in Vain: The Saga of the American Civil War. New York: HarperPerennial, 1991. ISBN 0-06-092116-1OCLC 24831189

- Leonard, Elizabeth D. All the Daring of the Soldier: Women of the Civil War Armies. New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 1999. ISBN 0-393-04712-1 OCLC 40543151

- Massey, Mary Elizabeth. Women in the Civil War. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994. ISBN 0-8032-8213-3 OCLC 29520663

- Middleton, Lee. Hearts of Fire--: Soldier Women of the Civil War : with an Addendum on Female Reenactors. Franklin, NC: Genealogy Pub. Service, 1993. ISBN 1-882755-00-6 OCLC 28767147

- Silvey, Anita. I'll Pass for Your Comrade: Women Soldiers in the Civil War. New York: Clarion Books, 2008. OCLC 261505452

- Smithsonian Institution, and DK Publishing, Inc. The Civil War: A Visual History. New York: DK Pub, 2011. ISBN 0-7566-7185-X OCLC 703637353

- Tsui, Bonnie. She Went to the Field: Women Soldiers of the Civil War. Guilford, Conn: TwoDot, 2006. ISBN 0-7627-4384-0 OCLC 154202084

External links

- Frances Clayton, Female Soldier In The Civil War

- Outlaw Women - Women Soldiers of the Civil War includes photos of Clalin in disguise

- Disguised as a man Frances Clalin served many months in Missouri artillery and cavalry units Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, slide in a slideshow "Revolutionary War" part of Issues in Violence and Aggression for Health Professionals course at University of Washington

- Women in The Civil War, Charity Post

- Female Soldiers in the Civil War. Archived 2015-08-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Women Soldiers of the Civil War.

- Covert Force.