Convoy PQ 11

| Convoy PQ 11 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Arctic Convoys of the Second World War | |||||||

The Norwegian and the Barents seas, site of the Arctic convoys | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Hans-Jürgen Stumpff Hermann Böhm | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

13 Freighters 15 Escorts (in relays) | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| No losses | No losses | ||||||

Convoy PQ 11 (14–22 February 1942) was an Arctic convoy sent from Britain by the Western Allies to aid the Soviet Union during the Second World War. The voyage took place amidst storms, fog and the almost permanent darkness of the Arctic winter. The convoy was not found by German U-boats or reconnaissance aircraft from Norway and reached at Murmansk without loss.

The commander of the Home Fleet, John Tovey, made representations to the Soviet authorities to rid the Kola Inlet of German U-boats, to provide air cover for convoys as they arrived and to send more escorts for the mid-part of the convoy route between Jan Mayen and Bear Island.

To be ready for attacks by German surface ships the British prepared to send a distant escort of battleships and aircraft carriers to support the close convoy escorts and to sail outbound and homeward convoys at the same time, for both to benefit from the distant escort. Convoy PQ 12 and Convoy QP 8 were opposed by German ships in Operation Sportpalast.

Background

Lend-lease

After Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the USSR, began on 22 June 1941, the UK and USSR signed an agreement in July that they would "render each other assistance and support of all kinds in the present war against Hitlerite Germany".[1] Before September 1941 the British had dispatched 450 aircraft, 22,000 long tons (22,000 t) of rubber, 3,000,000 pairs of boots and stocks of tin, aluminium, jute, lead and wool. In September British and US representatives travelled to Moscow to study Soviet requirements and their ability to meet them. The representatives of the three countries drew up a protocol in October 1941 to last until June 1942 and to agree new protocols to operate from 1 July to 30 June of each following year until the end of Lend-Lease. The protocol listed supplies, monthly rates of delivery and totals for the period.[2]

The first protocol specified the supplies to be sent but not the ships to move them. The USSR turned out to lack the ships and escorts and the British and Americans, who had made a commitment to "help with the delivery", undertook to deliver the supplies for want of an alternative. The main Soviet need in 1941 was military equipment to replace losses because, at the time of the negotiations, two large aircraft factories were being moved east from Leningrad and two more from Ukraine. It would take at least eight months to resume production, until when, aircraft output would fall from 80 to 30 aircraft per day. Britain and the US undertook to send 400 aircraft a month, at a ratio of three bombers to one fighter (later reversed), 500 tanks a month and 300 Bren gun carriers. The Anglo-Americans also undertook to send 42,000 long tons (43,000 t) of aluminium and 3, 862 machine tools, along with sundry raw materials, food and medical supplies.[2]

British grand strategy

The growing German air strength in Norway and increasing losses to convoys and their escorts, led Rear-Admiral Stuart Bonham Carter, commander of the 18th Cruiser Squadron, Admiral sir John Tovey, Commander in Chief Home Fleet and Admiral Sir Dudley Pound the First Sea Lord, the professional head of the Royal Navy, unanimously to advocate the suspension of Arctic convoys during the summer months.[3]

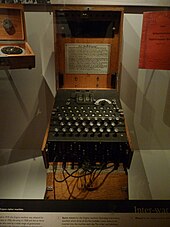

Bletchley Park

The British Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) based at Bletchley Park housed a small industry of code-breakers and traffic analysts. By June 1941, the German Enigma machine Home Waters (Heimish) settings used by surface ships and U-boats could quickly be read. On 1 February 1942, the Enigma machines used in U-boats in the Atlantic and Mediterranean were changed but German ships and the U-boats in Arctic waters continued with the older Heimish (Hydra from 1942, Dolphin to the British). By mid-1941, British Y-stations were able to receive and read Luftwaffe W/T transmissions and give advance warning of Luftwaffe operations. In 1941, naval Headache personnel, with receivers to eavesdrop on Luftwaffe wireless transmissions, were embarked on warships.[4]

B-Dienst

The rival German Beobachtungsdienst (B-Dienst, Observation Service) of the Kriegsmarine Marinenachrichtendienst (MND, Naval Intelligence Service) had broken several Admiralty codes and cyphers by 1939, which were used to help Kriegsmarine ships elude British forces and provide opportunities for surprise attacks. From June to August 1940, six British submarines were sunk in the Skaggerak using information gleaned from British wireless signals. In 1941, B-Dienst read signals from the Commander in Chief Western Approaches informing convoys of areas patrolled by U-boats, enabling the submarines to move into "safe" zones.[5] B-Dienst had broken Naval Cypher No 3 in February 1942 and by March was reading up to 80 per cent of the traffic, which continued until 15 December 1943. By coincidence, the British lost access to the Shark cypher and had no information to send in Cypher No 3 which might compromise Ultra.[6] In early September, Finnish Radio Intelligence deciphered a Soviet Air Force transmission which divulged the convoy itinerary, which was forwarded to the Germans.[7]

Arctic Ocean

Between Greenland and Norway are some of the most stormy waters of the world's oceans, 890 mi (1,440 km) of water under gales full of snow, sleet and hail.[8] The cold Arctic water was met by the Gulf Stream, warm water from the Gulf of Mexico, which became the North Atlantic Drift. Arriving at the south-west of England the drift moves between Scotland and Iceland; north of Norway the drift splits. One stream bears north of Bear Island to Svalbard and a southern stream follows the coast of Murmansk into the Barents Sea. The mingling of cold Arctic water and warmer water of higher salinity generates thick banks of fog for convoys to hide in but the waters drastically reduced the effectiveness of ASDIC as U-boats moved in waters of differing temperatures and density.[8]

In winter, polar ice can form as far south as 50 mi (80 km) off the North Cape and in summer it can recede to Svalbard. The area is in perpetual darkness in winter and permanent daylight in the summer and can make air reconnaissance almost impossible.[8] Around the North Cape and in the Barents Sea the sea temperature rarely rises about 4° Celsius and a man in the water will die unless rescued immediately.[8] The cold water and air makes spray freeze on the superstructure of ships, which has to be removed quickly to avoid the ship becoming top-heavy. Conditions in U-boats were, if anything, worse, the boats having to submerge in warmer water to rid the superstructure of ice. Crewmen on watch were exposed to the elements, oil lost its viscosity; nuts froze and sheared off bolts. Heaters in the hull wee too demanding of current and could not be run continuously.[9]

Prelude

Kriegsmarine

German naval forces in Norway were commanded by Hermann Böhm, the Kommandierender Admiral Norwegen. In 1941, British Commando raids on the Lofoten Islands (Operation Claymore and Operation Anklet) led Adolf Hitler to order U-boats to be transferred from the Battle of the Atlantic to Norway and on 24 January 1942, eight U-boats were ordered to the area of Iceland–Faroes–Scotland. Two U-boats were based in Norway in July 1941, four in September, five in December and four in January 1942.[10] By mid-February twenty U-boats were anticipated in the region, with six based in Norway, two in Narvik or Tromsø, two at Trondheim and two at Bergen. Hitler contemplated establishing a unified command but decided against it. The German battleship Tirpitz arrived at Trondheim on 16 January, the first ship of a general move of surface ships to Norway. British convoys to Russia had received little attention since they averaged only eight ships each and the long Arctic winter nights negated even the limited Luftwaffe effort that was available.[11]

Luftflotte 5

In mid-1941, Luftflotte 5 (Air Fleet 5) had been re-organised for Operation Barbarossa with Luftgau Norwegen (Air Region Norway) was headquartered in Oslo. Fliegerführer Stavanger (Air Commander Stavanger) the centre and north of Norway, Jagdfliegerführer Norwegen (Fighter Leader Norway) commanded the fighter force and Fliegerführer Kerkenes (Oberst [colonel] Andreas Nielsen) in the far north had airfields at Kirkenes and Banak. The Air Fleet had 180 aircraft, sixty of which were reserved for operations on the Karelian Front against the Red Army. The distance from Banak to Archangelsk was 560 mi (900 km) and Fliegerführer Kerkenes had only ten Junkers Ju 88 bombers of Kampfgeschwader 30, thirty Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive-bombers ten Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters of Jagdgeschwader 77, five Messerschmitt Bf 110 heavy fighters of Zerstörergeschwader 76, ten reconnaissance aircraft and an anti-aircraft battalion.[12]

Sixty aircraft were far from adequate in such a climate and terrain where "there is no favourable season for operations". The emphasis of air operations changed from army support to anti-shipping operations as Allied Arctic convoys became more frequent.[12] Hubert Schmundt, the Admiral Nordmeer noted gloomily on 22 December 1941 that the number long-range reconnaissance aircraft was exiguous and from 1 to 15 December only two Ju 88 sorties had been possible. After the Lofoten Raids, Schmundt wanted Luftflotte 5 to transfer aircraft to northern Norway but its commander, Generaloberst Hans-Jürgen Stumpff, was reluctant to deplete the defences of western Norway. Despite this some air units were transferred, a catapult ship (Katapultschiff), MS Schwabenland, was sent to northern Norway and Heinkel He 115 floatplane torpedo-bombers, of Küstenfliegergruppe 1./406 was transferred to Sola. By the end of 1941, III Gruppe, KG 30 had been transferred to Norway and in the new year, another Staffel of Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Kondors from Kampfgeschwader 40 (KG 40) had arrived. Luftflotte 5 was also expecting a Gruppe comprising three Staffeln of Heinkel He 111 torpedo-bombers.[13]

Arctic convoys

In October 1941, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, made a commitment to send a convoy to the Arctic ports of the USSR every ten days and to deliver 1,200 tanks a month from July 1942 to January 1943, followed by 2,000 tanks and another 3,600 aircraft in excess of those already promised.[1][a] The first convoy was due at Murmansk around 12 October and the next convoy was to depart Iceland on 22 October. A motley of British, Allied and neutral shipping loaded with military stores and raw materials for the Soviet war effort would be assembled at Hvalfjörður (Hvalfiord) in Iceland, convenient for ships from both sides of the Atlantic.[15] By late 1941, the convoy system used in the Atlantic had been established on the Arctic run; a convoy commodore ensured that the ships' masters and signals officers attended a briefing to make arrangements for the management of the convoy, which sailed in a formation of long rows of short columns. The commodore was usually a retired naval officer or a Royal Naval Reserveist and would be aboard one of the merchant ships (identified by a white pendant with a blue cross). The commodore was assisted by a Naval signals party of four men, who used lamps, semaphore flags and telescopes to pass signals in code.[16]

In large convoys, the commodore was assisted by vice- and rear-commodores with whom he directed the speed, course and zig-zagging of the merchant ships and liaised with the escort commander.[16][b] By the end of 1941, 187 Matilda II and 249 Valentine tanks had been delivered, comprising 25 per cent of the medium-heavy tanks in the Red Army and 30 to 40 per cent of the medium-heavy tanks defending Moscow. In December 1941, 16 per cent of the fighters defending Moscow were Hurricanes and Tomahawks from Britain; by 1 January 1942, 96 Hurricane fighters were flying in the Soviet Air Forces (Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily, VVS). The British supplied radar apparatuses, machine tools, ASDIC and other commodities.[17] During the summer months, convoys went as far north as 75 N latitude then south into the Barents Sea and to the ports of Murmansk in the Kola Inlet and Archangel in the White Sea. In winter, due to the polar ice expanding southwards, the convoy route ran closer to Norway.[18] The voyage was between 1,400 and 2,000 nmi (2,600 and 3,700 km; 1,600 and 2,300 mi) each way, taking at least three weeks for a round trip.[19]

Convoy escorts

The escorts were joined by the Flower-class corvette HMS Oxlip from Iceland, convoy escorts by this time comprising ships from different commands, which required relays of ships. The complexity of convoy escort operations required organisation by the Rear-Admiral, Home Fleet Destroyers, Robert Burnett, at Scapa Flow, the base of the Home Fleet. Sweetbriar and Oxlip had been detached from Western Approaches Command for the convoy. Oxlip had been on a Patrol White in the Denmark Strait and then refuelled in Seyðisfjörður on the east coast of Iceland to sail to meet Convoy PQ 11, which looked like "an undistinguished collection of grey-hulled ships low in the water".[20]

Convoy PQ 11

Convoy PQ 11 assembled at Loch Ewe in Scotland and sailed on 6 February 1942 for Kirkwall in the Orkneys, where storms prevented the convoy from sailing until 14 February.[21] The convoy was the first to have Hunt-class destroyers and Flower-class corvettes among the escorts.[22]

Voyage

PQ 11 consisted of 13 merchant ships; eight British, two Soviet, one American, one of Panamanian and one of Honduran registry. The convoy was escorted by two destroyers, Airedale and Middleton, the two corvettes and the Anti submarine warfare (ASW) Trawlers Blackfly, Cape Argona and Cape Mariato until 17 February and the minesweepers Niger (Senior Officer Escort) and Hussar, Sweetbriar joined on 17 February when the first relay departed.[22] The convoy managed an average of 8 kn (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) in cloud, fog and gales, spray freezing on the superstructures of the ships. As soon as there was a lull in a storm the crews cleared the ice with steam hoses, picks and shovels to prevent the ships from becoming top-heavy. Station keeping by the escorts was made easier with type 271 radar and the convoy commodore was praised for his skill in preventing the convoy from straggling too much, despite the fog. The convoy went undetected by German aircraft or U-boats in the continuous darkness of the polar night, the convoy to escape attack from the German air and naval forces in Norway. As the convoy approached the Russian coast the cruiser HMS Nigeria, based in Russia joined the convoy. On the last day of the voyage the convoy was accompanied by two Soviet destroyers and the minesweepers Harrier, Hazard and Salamander of the 6th Minesweeping Flotilla based at Murmansk.[23]

Aftermath

Convoy PQ 11 was never found by the German forces based in Norway and arrived at Murmansk without loss but the Admiralty knew that this might not last much longer as the increasing hours of daylight were to the disadvantage of Allied convoys when it would be up to three months before the polar ice receded and convoys could sail further away from the Norwegian coast. Tovey sent the captain of the cruiser Nigeria and commander of the 10th Cruiser Squadron, Rear-Admiral Harold Burrough, who was in Murmansk during February to the Russian authorities to increase its anti-submarine effort off the Kola Inlet and to furnish land-based fighter cover for convoys as they approached their destination. The accumulation of German surface ships at Trondheim was increasing the anxiety of the Admiralty staff who also wanted more Soviet escorts for the route between Jan Mayen and Bear Island (Bjørnøya) where they anticipated attacks by German ships, the last part of the route being left to U-boats and aircraft. Ships of the Home Fleet would be needed for distant cover against a German surface ship operation on the first half of the convoy route and Tovey asked that the next outbound and homeward convoys, Convoy PQ 12 from Iceland and Convoy QP 8 from Murmansk sail at the same time (1 March) so that Convoy QP 8 would be covered by the same Home Fleet sortie. The close convoy escort was to be reinforced, Coastal Command would increase its reconnaissance of the fiords around Trondheim to supplement the watch being kept by submarines and long-range Liberator patrols would be flown to the north-east from Iceland. Convoy PQ 12 and Convoy QP 8 were opposed by German ships in Operation Sportpalast.[24]

Merchant ships

| Name | Year | Flag | GRT | No. | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashkhabad | 1917 | 5,284 | 17 | ||

| Barrwhin | 1929 | 4,998 | 29 | ||

| City Of Flint | 1920 | 4,963 | 20 | ||

| Daldorch | 1930 | 5,571 | 30 | ||

| Empire Baffin | 1941 | 6,978 | 41 | Arrived Murmansk 24 February | |

| Empire Magpie | 1919 | 6,211 | 19 | Vice-Convoy Commodore | |

| Hartlebury | 1934 | 5,082 | 34 | ||

| Kingswood | 1929 | 5,080 | 29 | Convoy Commodore | |

| Lowther Castle | 1937 | 5,171 | 37 | ||

| Makawao | 1921 | 3,253 | 21 | ||

| Marylyn | 1930 | 4,555 | 30 | ||

| North King | 1903 | 4,934 | 03 | ||

| Stepan Khalturin | 1921 | 2,498 | 21 |

Escorts

Notes

- ^ In October 1941, the unloading capacity of Archangel was 300,000 long tons (300,000 t), Vladivostok (Pacific Route) 140,000 long tons (140,000 t) and 60,000 long tons (61,000 t) in the Persian Gulf (for the Persian Corridor route) ports.[14]

- ^ Code-books were carried in a weighted bag which was to be dumped overboard to prevent capture.[16]

- ^ Convoys had a standard formation of short columns, number 1 to port in the direction of travel. Each position in the column was numbered; 11 was the first ship in column 1 and 12 was the second ship in the column; 21 was the first ship in column 2.[26]

Footnotes

- ^ a b Woodman 2004, p. 22.

- ^ a b Hancock & Gowing 1949, pp. 359–362.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Macksey 2004, pp. 141–142; Hinsley 1994, pp. 141, 145–146.

- ^ Kahn 1973, pp. 238–241.

- ^ Budiansky 2000, pp. 250, 289.

- ^ FIB 1996.

- ^ a b c d Claasen 2001, pp. 195–197.

- ^ Paterson 2016, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Rahn 2001, p. 348.

- ^ Claasen 2001, pp. 190–192, 194.

- ^ a b Claasen 2001, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Claasen 2001, pp. 189–194.

- ^ Howard 1972, p. 44.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Woodman 2004, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Edgerton 2011, p. 75.

- ^ Roskill 1962, p. 119.

- ^ Butler 1964, p. 507.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 60–62; Rohwer & Hümmelchen 2005, p. 141.

- ^ a b Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 27.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Roskill 1962, pp. 119–122.

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 26.

- ^ Ruegg & Hague 1993, p. 31, inside front cover.

- ^ Woodman 2004, pp. 60–62.

- ^ Woodman 2004, p. 60.

References

Books

- Boog, H.; Rahn, W.; Stumpf, R.; Wegner, B. (2001). The Global War: Widening of the Conflict into a World War and the Shift of the Initiative 1941–1943. Germany in the Second World War. Vol. VI. Translated by Osers, E.; Brownjohn, J.; Crampton, P.; Willmot, L. (Eng trans. Oxford University Press, London ed.). Potsdam: Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt (Research Institute for Military History). ISBN 0-19-822888-0.

- Rahn, W. "Part III The War at Sea in the Atlantic and in the Arctic Ocean. III. The Conduct of the War in the Atlantic and the Coastal Area (b) The Third Phase, April–December 1941: The Extension of the Areas of Operations". In Boog et al. (2001).

- Budiansky, S. (2000). Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War II. New York: The Free Press (Simon & Schuster). ISBN 0-684-85932-7 – via Archive Foundation.

- Butler, J. R. M. (1964). Grand Strategy: June 1941 – August 1942 (Part II). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. III. London: HMSO. OCLC 504770038.

- Claasen, A. R. A. (2001). Hitler's Northern War: The Luftwaffe's Ill-fated Campaign, 1940–1945. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1050-2.

- Edgerton, D. (2011). Britain's War Machine: Weapons, Resources and Experts in the Second World War. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9918-1.

- Hancock, W. K.; Gowing, M. M. (1949). Hancock, W. K. (ed.). British War Economy. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Civil Series. London: HMSO. OCLC 630191560.

- Hinsley, F. H. (1994) [1993]. British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its Influence on Strategy and Operations. History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series (2nd rev. abr. ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630961-7.

- Howard, M. (1972). Grand Strategy: August 1942 – September 1943. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. IV. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630075-1 – via Archive Foundation.

- Kahn, D. (1973) [1967]. The Codebreakers: The Story of Secret Writing (10th abr. Signet, Chicago ed.). New York: Macmillan. LCCN 63-16109. OCLC 78083316.

- Macksey, K. (2004) [2003]. The Searchers: Radio Intercept in two World Wars (Cassell Military Paperbacks ed.). London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-36651-4.

- Paterson, Lawrence (2016). Steel and Ice: The U-Boat Battle in the Arctic and Black Sea 1941–45. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-258-4.

- Rohwer, Jürgen; Hümmelchen, Gerhard (2005) [1972]. Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (3rd rev. ed.). London: Chatham. ISBN 1-86176-257-7.

- Roskill, S. W. (1962) [1956]. The Period of Balance. History of the Second World War: The War at Sea 1939–1945. Vol. II (3rd impression ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 174453986. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014.

- Ruegg, Bob; Hague, Arnold (1993) [1992]. Convoys to Russia (2nd rev. exp. pbk. ed.). Kendal: World Ship Society. ISBN 978-0-905617-66-4.

- Woodman, Richard (2004) [1994]. Arctic Convoys 1941–1945. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5752-1.

Websites

- "Birth of Radio Intelligence in Finland and its Developer Reino Hallamaa". Pohjois–Kymenlaakson Asehistoriallinen Yhdistys Ry (North-Karelia Historical Association Ry) (in Finnish). 1996. Retrieved 1 July 2024.

Further reading

- Blair, Clay (1996). Hitler's U-Boat War: The Hunters 1939–42. Vol. I. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-35260-8.

- Kemp, Paul (1993). Convoy! Drama in Arctic Waters. London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 1-85409-130-1 – via Archive Foundation.

- Schofield, Bernard (1964). The Russian Convoys. London: BT Batsford. OCLC 906102591 – via Archive Foundation.