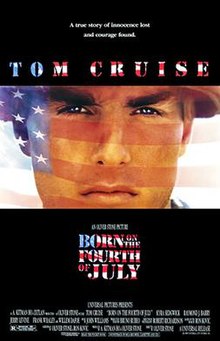

Born on the Fourth of July (film)

| Born on the Fourth of July | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

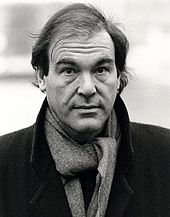

| Directed by | Oliver Stone |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Born on the Fourth of July by Ron Kovic |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Richardson |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | John Williams |

Production company | Ixtlan Productions[1] |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 145 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $17.8 million[1] |

| Box office | $162 million[3] |

Born on the Fourth of July is a 1989 American epic biographical anti-war drama film that is based on the 1976 autobiography of Ron Kovic. Directed by Oliver Stone, and written by Stone and Kovic, it stars Tom Cruise, Kyra Sedgwick, Raymond J. Barry, Jerry Levine, Frank Whaley, and Willem Dafoe. The film depicts the life of Kovic (Cruise) over a 20-year period, detailing his childhood, his military service and paralysis during the Vietnam War, and his transition to anti-war activism. It is the second installment in Stone's trilogy of films about the Vietnam War, following Platoon (1986) and preceding Heaven & Earth (1993).

Producer Martin Bregman acquired the film rights to the book in 1976 and hired Stone, also a Vietnam veteran, to co-write the screenplay with Kovic, who would be played by Al Pacino. When Stone optioned the book in 1978, the film adaptation became mired in development hell after Pacino and Bregman left, which resulted in him and Kovic putting the film on hold. After the release of Platoon, the project was revived at Universal Pictures, with Stone attached to direct. Shot on locations in the Philippines, Texas and Inglewood, California, principal photography took place from October 1988 to December, lasting 65 days of filming. The film went over its initial $14 million production budget and ended up costing $17.8 million after reshoots.

Upon release, Born on the Fourth of July was praised by critics for its story, Cruise's performance and Stone's direction. The film was successful at the box office as it grossed over $162 million worldwide, becoming the tenth highest-grossing film of 1989. At the 62nd Academy Awards, it received eight nominations, including Best Picture and Best Actor for Cruise, his first nomination, and the film won for Best Director, Stone's second in that category, and Best Film Editing. The film also won four Golden Globe Awards for Best Motion Picture – Drama, Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama, Best Director and Best Screenplay.

Plot

In 1956 Massapequa, New York, 10-year-old Ron Kovic is playing with his friends in a forest. On his Fourth of July birthday, he attends an Independence Day parade with his family and best friend Donna. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy's televised inaugural address inspires a teenage Kovic to join the United States Marine Corps. After attending an impassioned lecture by two Marine recruiters visiting his high school, he enlists. His decision receives support from his mother, but upsets his father, a World War II veteran who lost many of his friends to the war. Kovic goes to his prom, dances with Donna and kisses her before leaving for recruit training.

In October 1967, Kovic is now a Marine sergeant on a reconnaissance mission in Vietnam, during his second tour of duty. He and his unit kill a number of Vietnamese villagers after mistaking them for enemy combatants. After encountering enemy fire, they flee the village and abandon its sole survivor, a crying baby. During the retreat, Kovic accidentally kills Wilson, a young private in his platoon. He reports the action to his superior, who ignores the claim and advises him not to say anything else. In January 1968, Kovic is critically wounded during a firefight, but is rescued by a fellow Marine. Paralyzed from the mid-chest down, he spends several months in recovery at the Bronx Veterans Hospital in New York. Conditions in the underfunded and understaffed hospital are poor; the doctors, nurses and orderlies ignore patients, abuse drugs, and operate using old equipment. Against his doctors' requests, Kovic desperately tries to walk again with the use of braces and crutches, only to severely injure one of his legs, nearly requiring its amputation.

In 1969, Kovic, now permanently using a wheelchair, returns home and turns to alcohol to cope with his growing depression and disillusionment. During an Independence Day parade, he is asked to give a speech, but is unable to finish after he hears a crying baby in the crowd, triggering a flashback to Vietnam. Kovic visits Donna in Syracuse, New York, where the two reminisce. While attending a vigil for the victims of the Kent State shootings, they are separated when Donna and other protestors are arrested by police.

In Massapequa, a drunken Kovic has a heated argument with his mother, and his father decides to send him to Villa Dulce, a Mexican haven for wounded Vietnam veterans. He has his first sexual encounter with a prostitute, whom he falls for until he sees her with another customer. Kovic befriends Charlie, another paraplegic, and the two decide to travel to another village after getting kicked out of a bar. After annoying their taxicab driver, they are stranded on the side of the road, and an argument turns into a fight. They are picked up by a passing motorist who takes them back to Villa Dulce.

Kovic travels to Armstrong, Texas, where he locates Wilson's tombstone. He then visits the fallen Marine's family in Georgia to confess his guilt. Wilson's widow Jamie, states that she can't forgive him, and that any kind of forgiveness would be left up to him and God; while his parents are more sympathetic. In 1972, Kovic joins the organization Vietnam Veterans Against the War, and travels to the Republican National Convention in Miami, Florida. As Richard Nixon is giving an acceptance speech for his presidential nomination, Kovic expresses to a news reporter his hatred for the war and the government for abandoning the American people. His comments enrage Nixon's supporters, and his interview is cut short when police attempt to remove and arrest him and other protestors. Kovic and the veterans manage to break free from the officers, regroup, and charge the hall again, though not successfully. In 1976, Kovic delivers a public address at the Democratic National Convention in New York City, following the publication of his autobiography.

Cast

- Tom Cruise as Sergeant Ron Kovic

- Bryan Larkin as Young Ron

- Willem Dafoe as Charlie

- Kyra Sedgwick as Donna

- Jessica Prunell as Young Donna

- Raymond J. Barry as Eli Kovic

- Jerry Levine as Steve Boyer

- Frank Whaley as Timmy

- Caroline Kava as Patricia Kovic

- Cordelia Gonzalez as Maria Elena - Villa Dulce

- Ed Lauter as Legion Commander

- John Getz as Marine Major - Vietnam

- Michael Wincott as Vet #1 - Villa Dulce

- Edith Díaz as Madame - Villa Dulce

- Richard Grusin as Coach - Massapequa

- Stephen Baldwin as Billy Vorsovich

- Bob Gunton as Doctor - Veterans Hospital

- Jason Gedrick as Martinez - Vietnam

- Richard Panebianco as Joey Walsh

- Anne Bobby as Susanne Kovic

- David Warshofsky as Lieutenant - Vietnam

- Reg E. Cathey as Speaker - Syracuse

- Josh Evans as Tommy Kovic

- Bruce MacVittie as Patient #1 - Veterans Hospital

- Lili Taylor as Jamie Wilson

- David Herman as Patient #2 - Veterans Hospital

- Andrew Lauer as Vet #2 - Villa Dulce

- Tom Sizemore as Vet #3 - Villa Dulce

- Tom Berenger as Gunnery Sergeant Hayes - Marine Recruiter

- Peter Crombie as Undercover Vet

- Beau Starr as Phil, man in Arthur's Bar

- Vivica Fox as Hooker

- John C. McGinley as Official #1 - Democratic Convention (Pushing Kovic's Wheelchair)

- Wayne Knight as Official #2 - Democratic Convention

- Richard Haus as Marine Sergeant - 2nd Recruiter

- Mark Moses as Optimistic Doctor

- Holly Marie Combs as Jenny

- Daniel Baldwin as Veteran No #1

- William Baldwin as U.S. Marine - Vietnam

In addition, decorated Marine and Vietnam War veteran Dale Dye appears as an infantry colonel, Oliver Stone appears as a TV reporter, the real Ron Kovic appears as a wheelchair-bound veteran in the opening sequence, Chicago Seven anti-war protester Abbie Hoffman appears as a student strike organizer at Syracuse University, and singer Edie Brickell appears as a folksinger in Syracuse. Hoffman died before the film was released, with an "In Memoriam" in his honor shown in the closing credits.

Production

Development

Al Pacino expressed interest in portraying Ron Kovic after watching the Vietnam veteran's televised appearance at the 1976 Democratic National Convention and reading his autobiography. He also turned down starring roles in the Vietnam War-themed films Coming Home (1978) and Apocalypse Now (1979), the former for which Kovic would act as a consultant.[4] Kovic met with Pacino in New York, where they discussed adapting the book to film.[4] In September 1976, Pacino's manager, producer Martin Bregman, contacted Kovic's agent and entered into negotiations for the film rights. The following October, Bregman's production company Artists Entertainment Complex acquired the rights for $150,000.[4] Filming was scheduled to begin in June 1977[4] with Paramount Pictures acting as distributor,[1] but the project fell apart. Bregman and Pacino were unhappy with the script,[4] and the studio dropped the film.[1]

In 1977, Bregman hired Oliver Stone, also a Vietnam veteran, to help write the screenplay.[4][5] At the time, Stone had been developing Platoon (1986), and an unproduced sequel script titled Second Life, that was inspired by his own life after the war.[6] He and Kovic bonded over their experiences during the war, and they began work on a new script in 1978 after Stone optioned the book.[1] Stone also discussed the adaptation with William Friedkin, who turned down an opportunity to direct in favor of The Brink's Job (1978).[5] After Bregman secured financing from German investors,[5] the film briefly continued development at United Artists[1] before moving to Orion Pictures.[5] Daniel Petrie was hired to direct, but several weeks before rehearsals, the investors withdrew from funding the film.[5][7] After the project moved to Universal Pictures, Bregman and Pacino left the film.[7] Bregman deemed the project impossible, and felt it would be overshadowed by the success of Coming Home.[1] Stone and Kovic grew frustrated with the troubled pre-production and dropped the project, though Stone expressed his hope to return and make the film at a later time.[8] Stone promised Kovic that if his career took off, he would return to Kovic to revive the project.[9] Kovic stated that after the release of Platoon, Stone called Kovic and told him he was ready to return working on the film.[9]

In April 1987, John Daly, chairman and CEO of the English-based Hemdale Film Corporation, announced that it was producing the film, which would act as a sequel to Platoon.[10] The studio entered into negotiations to finance the film in May 1988 with a $20 million budget, but it later withdrew from funding the film.[1][11] Stone was announced as director in June 1988, and his Ixtlan Productions banner was enlisted as a production company.[11][12] Tom Pollock, president of Universal Pictures, read the script as Stone was developing Wall Street (1987), and the studio allocated a $14 million budget on the condition that a major star appears in the lead role.[8] Stone and Kovic then revised the script, adding the latter's appearance at the 1976 Democratic National Convention.[13]

Casting

Sean Penn, Charlie Sheen and Nicolas Cage were among those considered by Stone to portray Kovic.[14] In 1987, Stone's agent Paula Wagner had shown Platoon to Tom Cruise, after he had expressed interest in working with Stone.[13] Cruise met with Stone to discuss the role in January 1988.[8] The studio was concerned over the prospects of Cruise appearing as a dramatic film lead.[15][16] Stone, in particular, had dismissed his previous film Top Gun (1986) as a "fascist movie",[16] but expressed that he was drawn to Cruise's "Golden Boy" image. "I saw this kid who has everything," he stated. "And I wondered what would happen if tragedy strikes, if fortune denies him ... I thought it was an interesting proposition: What would happen to Tom Cruise if something goes wrong?"[8] Kovic was also wary of Cruise's casting, but relented when the actor visited him at his home in Massapequa, New York.[8]

Cruise spent one year preparing for the role.[17] He visited several veterans' hospitals, read various books on the Vietnam War and practiced riding in a wheelchair.[18] At one point during pre-production, Stone suggested that Cruise be injected with a chemical drug that would render him paralyzed for two days; Stone believed that the drug would help him realistically portray the difficulties of being a paraplegic. The insurance company responsible for the film vetoed the idea, believing that the drug would cause permanent incapacitation.[19] Kovic visited the production daily and would often participate in rehearsals with Cruise.[1] Kovic also appears in the film as a World War II veteran at an Independence Day parade who flinches in response to exploding firecrackers, a reflex that Cruise's character develops later in the film.[20] On July 3, 1989, following the end of reshoots, Kovic gave Cruise his Bronze Star Medal as a birthday present and in praise of his commitment to the role.[21][22]

Casting directors Risa Bramon Garcia and Billy Hopkins sought more than 200 actors for various speaking roles. They auditioned 2,000 child actors in Massapequa and hired 8,000 extras for scenes shot in Dallas, Texas.[23] For the Fourth of July parade sequences, student protests and presidential conventions, the production employed nearly 12,000 people from the National Paralysis Foundation, Campfire Girls and American Legion to appear as extras.[1] The film reunited Stone with several past collaborators who make brief appearances in the film. Tom Berenger, who worked with Stone on Platoon, plays Gunnery Sergeant Hayes, a Marine recruiter.[24] Michael Wincott, who had a supporting role in Talk Radio (1988), plays a wounded veteran in Mexico. John C. McGinley, in his fourth collaboration with Stone, plays an official at the 1976 Democratic Convention.[25] Mark Moses, who appeared in Platoon as Lieutenant Wolfe, plays an overwhelmed doctor at the VA hospital in the Bronx. Stone himself appears as a skeptical news reporter.[26]

To prepare the actors portraying Marines, military advisor Dale Dye organized one-week training missions, one in the United States, and the other in the Philippines where the battle sequences were to be filmed.[1][27][26] Abbie Hoffman, a Yippie activist, acted as a consultant who educated the cast about the peace movement. He also makes an appearance as a protestor in Syracuse, New York.[28] The film is dedicated to Hoffman, who died on April 12, 1989.[1]

Filming

Principal photography was scheduled to begin in September 1988, but did not commence until mid-October of that year.[1] Studio executive Pollock planned an initial budget of $14 million, but the film went over budget.[1][14][29] The high production costs prompted Stone and Cruise to waive their salaries and instead receive a percentage of the box office gross.[1][15][29] The final production cost of the film was $17.8 million.[1][14][29] The film was cinematographer Robert Richardson's fifth collaboration with Stone, and their first to be shot in the anamorphic format.[12] Richardson shot the film using Panavision cameras and lenses,[30][31] and primarily utilized 35 mm film stocks; 16 mm and Super 16 mm stocks were also used to film the scene of Kovic demonstrating at the 1972 Republican National Convention, blended with archive footage of the actual event.[32]

Filming began in Dallas, Texas,[19] for scenes set in the United States. The Elmwood neighborhood of Oak Cliff doubled for Massapequa. The Kimball High School band and staff appeared in the parade scenes and the dramatic prom scene featuring Sedgwick and Cruise.[1][33] The Dallas Convention Center was used to re-create the 1972 Republican National Convention in Miami, Florida. The filmmakers also shot scenes at the Parkland Memorial Hospital, which stood in for the Bronx Veterans Hospital in New York.[1] They also filmed on soundstages at Las Colinas Studios in Irving, Texas.[31] The Philippines stood in for scenes set in Vietnam and Mexico.[1] Stone originally wanted to shoot on location in Vietnam but was unable to do so, due to unresolved conflicts between that country and the United States.[34] Principal photography wrapped in December 1988, after 65 days of filming.[14][18][19]

After viewing a rough cut of the film, Universal demanded that the ending, which depicted Kovic's appearance at the 1976 Democratic National Convention, be reshot. The original scene was shot in Dallas, with 600 extras, but the studio was dissatisfied with the filmed footage, and requested that Stone make it "bigger and better".[1][35] The scene was reshot in July 1989 at The Forum arena in Inglewood, California.[1] Filming lasted one day, with 6,000 extras.[35] The reshoot ended up costing $500,000.[1][14][29]

Music

| Born on the Fourth of July (Motion Picture Soundtrack Album) | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album | |

| Released | December 19, 1989 |

| Length | 56:45 |

| Label | |

| Producer | John Williams |

The score was produced, composed and conducted by John Williams, who agreed to work on the film after viewing a rough cut version.[36] Recording sessions took place at 20th Century Fox Studios in Los Angeles, California.[37] Timothy Morrison, a member of the Boston Pops Orchestra, acted as a trumpeter.[36] Williams stated, "I knew immediately I would want a string orchestra to sing in opposition to all the realism on the screen, and then the idea came to have a solo trumpet – not a military trumpet, but an American trumpet, to recall the happy youth of [Kovic]."[36] The motion picture soundtrack album was released on December 19, 1989, by MCA Records. In addition to Williams's score, it features eight songs that appear in the film.[1][38] AllMusic's Tavia Hobbart wrote that the score "literally haunts you as you watch the movie. It's just as effective here."[37] Stephen Holden of The New York Times stated, "Mr. Williams's themes are melodically strong enough so that one could imagine them being developed into a full-blown symphonic poem."[39]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Artist | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall" | Bob Dylan | Edie Brickell & New Bohemians | 4:58 |

| 2. | "Born on the Bayou" | John Fogerty | The Broken Homes | 4:54 |

| 3. | "Brown Eyed Girl" | Van Morrison | Van Morrison | 3:07 |

| 4. | "American Pie" | Don McLean | Don McLean | 8:32 |

| 5. | "My Girl" | Smokey Robinson, Ronald White | The Temptations | 2:43 |

| 6. | "Soldier Boy" | Luther Dixon, Florence Greenberg | The Shirelles | 2:39 |

| 7. | "Venus" | Ed Marshall | Frankie Avalon | 2:21 |

| 8. | "Moon River" | Henry Mancini, Johnny Mercer | Henry Mancini | 2:41 |

| 9. | "Prologue" | John Williams | John Williams | 1:22 |

| 10. | "The Early Days, Massapequa, 1957" | John Williams | John Williams | 4:57 |

| 11. | "The Shooting of Wilson" | John Williams | John Williams | 5:07 |

| 12. | "Cua Viet River, Vietnam, 1968" | John Williams | John Williams | 5:02 |

| 13. | "Homecoming" | John Williams | John Williams | 2:38 |

| 14. | "Born on the Fourth of July" | John Williams | John Williams | 5:44 |

Release

Universal gave the film a platform release which involved showing it in select cities before expanding distribution in the following weeks. To qualify the film for awards consideration,[40] the studio issued a limited theatrical run in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and Toronto on December 20, 1989.[1] The film was released across North America on January 5, 1990,[3] playing at 1,310 theaters,[41][42] and expanding to 1,434 theaters by its eleventh week.[41][43] A heavily edited version of the film was scheduled for broadcast on CBS in early 1991, but was shelved by the network's executives due to the impending Persian Gulf War. The film had its network premiere on January 21, 1992.[1][44]

Home media

The film was released on VHS on August 9, 1990,[45] and DVD on October 31, 2000.[46] On January 16, 2001, it was again released on DVD as a part of the "Oliver Stone Collection", a box set of films directed by Stone.[47] Special features include an audio commentary by Stone, production notes, and cast and crew profiles.[48] A Special Edition DVD was released on October 5, 2010, containing the film, the commentary by Stone, as well as archive news footage from NBC News.[49] The film was released on HD DVD on June 12, 2007,[50] and on Blu-ray on July 3, 2012. The Blu-ray presents the film in 1080p high definition, and contains all the additional materials found on the Special Edition DVD.[51] A 4K UHD Blu-ray was released on November 12, 2024 featuring a new restoration from the original camera negative as was as new special features.[52]

Reception

Box office

The film grossed $172,021 on its first week of limited release, an average of $34,404 per theatre. More theatres were added on the following weekend, and it grossed a further $61,529 in its second weekend, with an overall gross of $937,946.[41] On its third weekend, the film entered wide release, grossing $11,023,650 and securing the number one position at the North American box office.[41][42] The film fell 27.2% the following week, grossing an additional $8,028,075 while remaining first in the top-ten rankings.[41][53] On its fifth weekend, it earned an additional $6,228,360 for an overall gross of $32,607,294.[54]

The film grossed $4,640,940 in its sixth weekend, dropping to second place behind Driving Miss Daisy.[41][55] The following weekend, it moved to third place, earning an additional $4,012,085.[41][56] On its eighth weekend, it had dropped to fourth place and earned $3,004,400.[41][57] It stayed in fifth place for the next three weekends, and by March 4, 1990, the film had an overall gross of $59,673,354.[41][43]

The film grossed $70,001,698 in North America[3] ($151,650,800 when adjusted for inflation),[58] and $91 million in other territories, for a worldwide total of $162,001,698.[3] In the United States and Canada, it was the seventeenth highest-grossing film of 1989.[59] Worldwide, it was the tenth highest-grossing film of 1989,[60] as well as Universal's second highest-grossing film released that year, behind Back to the Future Part II.[61]

Critical response

Based on 56 reviews, Born on the Fourth of July holds a score of 84% on review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, with an average rating of 7.50/10. The website's consensus reads, "Led by an unforgettable performance from Tom Cruise, Born on the Fourth of July finds director Oliver Stone tackling thought-provoking subject matter with ambitious élan."[62] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 75 out of 100 based on reviews from 16 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[63] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A−" on an A+ to F scale.[64]

David Denby of New York magazine, stated that the film was "a relentless but often powerful and heartbreaking piece of work, dominated by Tom Cruise's impassioned performance."[65] Richard Corliss of Time, Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times, Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune and Peter Travers of Rolling Stone also commended Cruise's performance.[21][66][67][68] Vincent Canby of The New York Times said the film was "the most ambitious nondocumentary film yet made about the entire Vietnam experience."[69] Janet Maslin, also writing for The New York Times, praised Stone's direction, writing that he "reaches out instantly to his audience's gut-level emotions and sustains a walloping impact for two and a half hours."[70] Internet reviewer James Berardinelli felt that the film's greatest accomplishment was "its contrasting of the glorious illusion of war as seen from thousands of miles away to the barbarity of it up-close."[71]

The Washington Post published two negative reviews; Hal Hinson called the film "alienating",[72] while Desson Howe was critical of Cruise's "whiny" performance.[73] Sheila Benson of the Los Angeles Times felt that the actor's portrayal of Kovic was lacking in character development.[74] Jonathan Rosenbaum derided the storytelling for "brimming with false uplift",[75] and Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly called the film "2 1/2 hours of self-righteousness masquerading as art."[76] Pauline Kael of The New Yorker wrote, "It's almost inconceivable that Ron Kovic was as innocent as the movie and the 1976 autobiography on which it's based make him out to be ... Kovic's book is simple and explicit; he states his case in plain, angry words. Stone's movie yells at you for two hours and twenty-five minutes."[77]

The film also received criticism for its dramatization of actual events, prompted by Kovic's declared decision to run for Congress as a Democratic opponent to Californian Republican Robert Dornan in the 38th congressional district. As a result, Born on the Fourth of July became Stone's first film to be publicly attacked in the media.[78] Dornan criticized the film for portraying Kovic as "[being] in a panic and mistakenly shooting his corporal to death in Vietnam, visiting prostitutes, abusing drugs and alcohol and cruelly insulting his parents". Kovic dismissed his comments as being part of a "hatred campaign",[79] and ultimately did not run for election.[78]

In a newspaper column, former White House Communications Director Pat Buchanan criticized the adaptation for deviating from the book, and concluded by calling Stone a "propagandist".[1][80] Republican State Senator Nancy Larraine Hoffmann, who took part in Syracuse University's 1970 peaceful protest of the Cambodian Campaign, was critical of the film's depiction of Syracuse police as "faceless people brutalizing peaceful protesters".[81] Following the film's wide release in January 1990, Stone wrote a letter apologizing to the city of Syracuse and its police officials.[82]

Accolades

The film received various awards and nominations, with particular recognition for the screenplay, Cruise's performance, Stone's direction and the score by John Williams. The National Board of Review named it one of the "Top 10 Films of 1989", ranking it at number one.[83] The film received five Golden Globe Award nominations[84] and won four for Best Motion Picture – Drama, Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama, Best Director and Best Screenplay, while Williams was nominated for Best Original Score.[85]

In February 1990, the film competed for the Golden Bear at the 40th Berlin International Film Festival, but lost to the American film Music Box (1990) and Czech film Larks on a String (1969).[86] That same month, the film garnered eight Academy Awards nominations, including Best Picture and Best Actor; its closest rival was Driving Miss Daisy, which received nine nominations.[87] At the 62nd Oscars, Stone won a second Academy Award for Best Director;[88] he had previously won the award for Platoon.[89] The film also won the Academy Award for Best Film Editing, beating out Driving Miss Daisy, The Bear, Glory and The Fabulous Baker Boys in that category.[88] At the 44th British Academy Film Awards in 1991, the film received two nominations for Best Actor in a Leading Role and Best Adapted Screenplay, but did not win in either category.[90]

On May 10, 2021, Cruise returned all three of his Golden Globe awards to the Hollywood Foreign Press Association due to controversy in its lack of diversity among its membership, including his Best Actor award for this film.[91]

See also

- Platoon, the first installment in Oliver Stone's Vietnam War trilogy

- Heaven & Earth, the third installment in Stone's Vietnam War trilogy

- Casualties of War, another 1989 film set during the Vietnam War, based on the 1966 incident on Hill 192

- Vietnam War in film

- United States–Vietnam relations

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z "AFI Catalog". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Born on the Fourth of July". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Born on the Fourth of July (1989)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 11 October 2009. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Mogk 2013, p. 221.

- ^ a b c d e Seitz 2016, p. 90.

- ^ Devine 2017, p. 338.

- ^ a b Dutka, Elaine (December 17, 1989). "The Latest Exorcism of Oliver Stone: With Ron Kovic's "Born on the Fourth of July", the film maker returns to Vietnam to cast out more of the war's demons (Page 2 of 5)". Los Angeles Times. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 6, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Dutka, Elaine (December 17, 1989). "The Latest Exorcism of Oliver Stone: With Ron Kovic's "Born on the Fourth of July", the film maker returns to Vietnam to cast out more of the war's demons (Page 3 of 5)". Los Angeles Times. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 6, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ a b "Veterans Ron Kovic, Oliver Stone on the True Cost of War (Video & Transcript)". Truthdig: Expert Reporting, Current News, Provocative Columnists. Archived from the original on 2019-06-20. Retrieved 2019-06-20.

- ^ Grove, Martin A. (April 1, 1987). "Hemdale celebrates 'Platoon' Oscar with plans for sequel". The Hollywood Reporter. p. 1.

- ^ a b Ryan, Desmond (June 10, 1988). "Another Vietnam Look From Oliver Stone". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Duchovnay 2004, p. 94.

- ^ a b Lavington 2011, p. 194.

- ^ a b c d e Lavington 2011, p. 195.

- ^ a b Gabriel, Trip (January 11, 1990). "Tom Cruise at the Crossroads". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ a b Stone 2001, p. 76.

- ^ Morton 2008, p. 120.

- ^ a b Dutka, Elaine (December 17, 1989). "The Latest Exorcism of Oliver Stone: With Ron Kovic's "Born on the Fourth of July", the film maker returns to Vietnam to cast out more of the war's demons (Page 4 of 5)". Los Angeles Times. p. 4. Archived from the original on July 6, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c Morton 2008, p. 122.

- ^ Lavington 2011, p. 197.

- ^ a b Corliss, Richard (December 25, 1989). "Tom Terrific". Time. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Morton 2008, p. 123.

- ^ Collins, Glenn (January 30, 1990). "For Casting, Countless Auditions And One Couch, Never Used". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (December 20, 1989). "How an All-American Boy Went to War and Lost His Faith". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 28, 2012. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Lavington 2011, p. 195-196.

- ^ a b Seitz 2017, p. 175.

- ^ Chutkow, Paul (December 17, 1989). "The Private War of Tom Cruise". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Lavington 2011, p. 196.

- ^ a b c d Dutka, Elaine (December 17, 1989). "The Latest Exorcism of Oliver Stone: With Ron Kovic's "Born on the Fourth of July", the film maker returns to Vietnam to cast out more of the war's demons (Page 5 of 5)". Los Angeles Times. p. 5. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Pubsun Corporation 1990, p. 41.

- ^ a b Fisher 1990, p. 27.

- ^ Ressner, Jeffrey (Fall 2012). "Breaking Conventions". DGA Quarterly. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Elmwood History". Elmwood Neighborhood Association. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "1990 - Drama: Born on the Fourth of July". Golden Globe Awards. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ a b Smith, Stacy Jenel (August 6, 1989). "Re-'Born' in July". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 29, 2015. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ a b c Dyer, Richard (August 31, 1989). "You Will Be Hearing From Him". The Boston Globe. p. 77.

- ^ a b "Born on the Fourth of July [Motion Picture Soundtrack Album]". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Born on the Fourth of July Soundtrack Details". SoundtrackCollector.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (January 28, 1990). "Recordings; The Image of Movie Music Is Changing Once Again". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Devine 2017, p. 337.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Born on the Fourth of July (1989) – Weekend Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ a b "Weekend Box Office Results for January 5-7, 1990". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ a b "Weekend Box Office Results for March 2-4, 1990". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ Gerber 2012, p. 113.

- ^ "Born on the Fourth of July (1989) - Misc Notes". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ "Born on the Fourth of July: Special Edition". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ "Oliver Stone Collection DVD: Any Given Sunday, JFK, Natural Born Killers, Heaven and Earth, Born on the Fourth of July, Wall Street, The Doors, Nixon, Talk Radio, U-Turn, Oliver Stone's America". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on June 6, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Born on the Fourth of July DVD: Special Edition". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Born on the Fourth of July DVD: Special Edition". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database – Born on the Fourth of July [61032866]". LaserDisc Database. Archived from the original on October 11, 2015. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Born on the Fourth of July Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on June 6, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Born on the Fourth of July gets 4K UHD in November". InsidePulse. Archived from the original on November 12, 2024. Retrieved November 12, 2024.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for January 12-14, 1990". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for January 19-21, 1990". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for January 26-28, 1990 - Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 16, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for February 2-4, 1990". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for February 9-11, 1990". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Top Grossing R Rated Movies at the Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "1989 Yearly Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "1989 Yearly Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "1989 Yearly Box Office Results (Universal)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Born on the Fourth of July (1989)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on September 10, 2009. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- ^ "Born on the Fourth of July Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Find CinemaScore" (Type "Born on the Fourth of July" in the search box). Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ Denby 1989, p. 101.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 20, 1989). "Born on the Fourth of July Movie Review (1989)". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (December 22, 1989). "Cruise Reborn As Actor In 'Born on the Fourth'". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Travers, Peter (December 20, 1989). "Born on the Fourth of July". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 17, 2015. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (December 20, 1989). "Review/Film; How an All-American Boy Went to War and Lost His Faith". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (December 31, 1989). "Film Film View: Oliver Stone Takes Aim At the Viewer's Viscera". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ Berardinelli, James (August 23, 2009). "Born on the Fourth of July". Reelviews Movie Reviews. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- ^ Hinson, Hal (January 5, 1990). "Born on the Fourth of July". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 18, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Howe, Desson (January 5, 1990). "Born on the Fourth of July". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Benson, Sheila (December 20, 1989). "Movie Review : Oliver Stone Goes to War Again : Drama: The maker of 'Platoon' touches the emotions but not the mind with 'Born on the Fourth of July.' Tom Cruise excels as disabled Vietnam War vet Ron Kovic". Los Angeles Times. p. 2 of 2. Archived from the original on April 26, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (January 5, 1990). "Born on the Fourth of July". Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (August 10, 1990). "Born on the Fourth of July". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ^ Kael 2011, p. 93.

- ^ a b Lavington 2011, p. 211.

- ^ Phillips, Richard (February 6, 1990). "Here's to a Nice Addiction". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 29, 2018. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ^ Buchanan, Patrick (1990-02-28). "Oliver Stone and the fiction of true films". The Southeast Missourian. p. 10A.

- ^ Ravo, Nick (January 15, 1990). "'Fourth of July' Unfair to Syracuse Police, Some Residents Say". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2018. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ^ "Stone publicly apologizes for his depiction of police". Deseret News. September 30, 1997. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ^ a b "1989 Archives". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ a b Thomas, Bob (December 27, 1989). "Romance Comedy, 2 War Films Each Get 5 Globe Nominations". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ a b "Winners & Nominees 1990". Golden Globe Awards. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ a b "Prizes & Honours 1990". Berlinale.de. Archived from the original on November 23, 2015. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ Easton, Nina J. (February 15, 1990). "'Driving Miss Daisy' Paces Academy Awards Race : 'Daisy' tops field with nine nominations followed by 'Fourth of July' with eight". Los Angeles Times. p. 1 of 3. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c "The 62nd Academy Awards (1990) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. 5 October 2014. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (March 31, 1987). "'Platoon' Wins Second Oscar as the Best Movie of 1986". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ a b "Film in 1991". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ Fulser, Jeremy (May 10, 2021). "Tom Cruise Returns His 3 Golden Globes in Protest Against HFPA". The Wrap. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ "The ASC -- Past ASC Awards". American Society of Cinematographers. Archived from the original on November 12, 2010. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ^ "1990 Artios Awards". Casting Society of America. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Berlinale Annual Archives 1990 Programme". berlinale.de. Archived from the original on May 8, 2005. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ^ "42nd Annual Directors Guild of America Awards". Directors Guild of America. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Matthews, Jack (December 18, 1989). "Spike Lee's 'Right Thing' Takes L.A. Film Critics' Top Award : Movies: The 26 members agreed on "My Left Foot," "sex, lies" and "Baker Boys" but split a tie for best actress between MacDowell and Pfeiffer". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (January 8, 1990). "U.s. Film Critics Pick 'Drugstore Cowboy' As Best". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ Kagan 2006, p. 297.

Books

- Denby, David (December 18, 1989). "Days of Rage". New York. Vol. 22, no. 50. p. 101. ISSN 0028-7369.

- Devine, Jeremy M. (2017), Vietnam at 24 Frames a Second: A Critical and Thematic Analysis of 360 Films About the Vietnam War, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-1-4766-0535-7

- Duchovnay, Gerald (June 17, 2004), ""Oliver Stone"", Film Voices: Interviews from Post Script, SUNY Press, p. 94, ISBN 978-0-7535-4766-3

- Fisher, Bob (February 1, 1990), "Born on the Fourth of July", American Cinematographer, 71 (2), Los Angeles, United States: American Society of Cinematographers: 27, ISSN 0002-7928

- Gerber, David A. (2012), ""Bitterness, Rage, and Redemption"", Disabled Veterans in History, University of Michigan Press, p. 113, ISBN 978-0-4720-3508-3

- Kael, Pauline (2011), 5001 Nights at the Movies, Henry Holt and Company, p. 93, ISBN 978-1-2500-3357-4

- Kagan, Jeremy Paul (2006), ""Biographies"", Directors Close Up: Interviews with Directors Nominated for Best Film by the Directors Guild of America, Scarecrow Press, p. 297, ISBN 978-0-8108-5712-4

- Lavington, Stephen (2011), ""Born on the Fourth of July (1989)"", Virgin Film: Oliver Stone, Random House, ISBN 978-0-7535-4766-3

- Mogk, Marie Evelyn (2013), "13. Born on the Fourth of July (Norden)", Different Bodies: Essays on Disability in Film and Television, McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-6535-4

- Morton, Andrew (2008), "Chapter 5", Tom Cruise: An Unauthorized Biography, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-1-4299-3390-2

- Pubsun Corporation (1990), "In Focus", The Film Journal, vol. 93

- Seitz, Matt Zoller (2016), "2. "Who's Gonna Love Me?"", The Oliver Stone Experience, Abrams Books, ISBN 978-1-6131-2814-5

- Seitz, Matt Zoller (2017), "4. Break on Through (1987–1991)", The Oliver Stone Experience (Text-Only Edition), Abrams Books, ISBN 978-1-6833-5190-0

- Stone, Oliver (2001), "Playboy Interview: Oliver Stone", Oliver Stone Interviews, Univ. Press of Mississippi, ISBN 978-1-5780-6303-1