Belgian Grand Prix

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps (intermittently; 1925–1939, 1947–1970, 1983–present) | |

| |

| Race information | |

|---|---|

| Number of times held | 79 |

| First held | 1925 |

| Most wins (drivers) | |

| Most wins (constructors) | |

| Circuit length | 7.004 km (4.352 miles) |

| Race length | 308.052 km (191.398 miles) |

| Laps | 44 |

| Last race (2023) | |

| Pole position | |

| |

| Podium | |

| |

| Fastest lap | |

| |

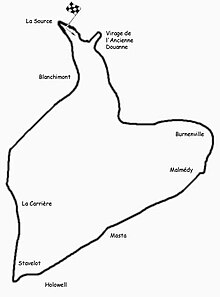

The Belgian Grand Prix (French: Grand Prix de Belgique; Dutch: Grote Prijs van België; German: Großer Preis von Belgien) is a motor racing event which forms part of the Formula One World Championship. The first national race of Belgium was held in 1925 at the Spa region's race course, an area of the country that had been associated with motor sport since the very early years of racing. To accommodate Grand Prix motor racing, the Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps race course was built in 1921 but until 1924 it was used only for motorcycle racing. After the 1923 success of the new 24 hours of Le Mans in France, the Spa 24 Hours, a similar 24-hour endurance race, was run at the Spa track.

Since its inception, Spa-Francorchamps has been known for its unpredictable weather. At one stage in its history it had rained at the Belgian Grand Prix for twenty years in a row. Frequently drivers confront a part of the course that is clear and bright while another stretch is rainy and slippery.

The Belgian Grand Prix was designated the European Grand Prix six times between 1925 and 1973, when this title was an honorary designation given each year to one Grand Prix race in Europe. It is one of the most popular races on the Formula One calendar, due to the scenic and historical Spa-Francorchamps circuit being a favourite of drivers and fans.

History

Spa-Francorchamps (pre-WWII) and Bois de la Cambre

In 1925, the first Belgian Grand Prix was held at the very fast, 9-mile Spa-Francorchamps circuit located in the Ardennes region of eastern Belgium, about half an hour from Liege. This race was won by the Italian works Alfa driver Antonio Ascari, whose son Alberto would win the race in 1952 and 1953. After winning the Belgian race, Antonio Ascari was killed in his next race at the 1925 French Grand Prix. The Grand Prix did not come back until 1930, and the circuit had been modified, bypassing the Malmedy chicane. The race was won by Louis Chiron, and in 1931, the Grand Prix had become something of an endurance race, with Briton William Grover-Williams and Caberto Conelli winning. 1933 was won by Tazio Nuvolari, and 1935 was won by Rudolf Caracciola in a Mercedes, by which time the circuit had re-installed the Malmedy Chicane. The 1939 race saw the birth of the Raidillon corner; it was a bypass of the Ancienne Douane section. In contrast to popular belief, only the small kink to the left at the bottom of the drop is named Eau Rouge, which directly leads into Raidillon, a very long right uphill corner;[3] and the tricky left blind corner at the top has no name. The conditions were dreadful, and the race was marred by the death of British driver Richard "Dick" Seaman while leading the race. Going into Clubhouse corner, Seaman was pushing hard; he skidded off the rain-soaked road, hit a tree and his Mercedes caught fire. Seaman received life-threatening burns, and he succumbed to his injuries later in hospital. The race was won by Seaman's teammate Hermann Lang. World War II broke out, and the Belgian Grand Prix did not return until June 1946, when the 2 to 4.5 litres race at the Bois de la Cambre public park in the Belgian capital of Brussels was won by Frenchman Eugène Chaboud in a Delage.

Old Spa-Francorchamps

Spa was modified to make it even faster, shortening it to 8.7 miles (14.1 km). All of the slow corners were taken out – the Stavelot hairpin was bypassed and made into a fast banked corner and the Malmedy chicane was also bypassed. At this time, every corner except La Source was ultra-high speed. Spa over this time became known as one of the most extreme, challenging and fearsome circuits in motorsports history. 1950 saw the introduction of the Formula One World Championship; the race was dominated by the Alfa Romeos of Argentine Juan Manuel Fangio and Italian Nino Farina. Their closest challenger, Alberto Ascari, ran into fuel problems and fell back. The race was won by Fangio, and Farina won the next year's race in his works Alfa after Fangio dropped back with hub problems. 1953 saw Ascari dominate in his Ferrari while the Maseratis fell apart. Fangio crashed and José Froilán González had a steering failure and stopped out near the banked Stavelot corner. 1955 saw Mercedes dominate, Fangio and his British teammate Stirling Moss led the race distance. Moss followed Fangio closely for most of the race, the Argentine took victory as he had the year before in a Maserati. 1956 saw a wet race, with Moss in a Maserati lead, and Fangio, now driving for Ferrari, made a bad start and dropped to fifth at the start, although he got up to second behind Moss. The track was drying, and Moss lost a wheel at Raidillon corner. He did not hit anything and went back to take over his teammate Cesare Perdisa's car and was able to finish 3rd. The gearbox in Fangio's car broke, and his teammate Peter Collins won the race.

The 1957 race was cancelled because there was no money for the race to be held, thanks to the extreme prices of fuel in Belgium and the Netherlands caused by the Suez crisis. 1958 saw Spa upgraded with new facilities, a resurfaced track and also the pit straight was made wider. But Spa had gained a reputation as a totally unforgiving, frightening and a very mentally challenging circuit, even in those safety-absent days, and most racing events there – particularly the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa – had smaller-than-average fields because a number of drivers feared the circuit and did not like racing there. The layout was still the same as before, and the extremely small, almost non-existent margin for error as described before had been realised very quickly. The circuit was extremely challenging, mainly because each corner on the circuit was so fast, and also because of the circuit's long length in addition to the fact that it was almost exclusively made up of fast corners and straights. The circuit was very fast, and each corner had to be taken correctly to maintain speed through the next one. Lifting off or taking the wrong racing line would result in several seconds being lost. Spa was located in a region where the weather was unpredictable; in many races there, while one part of the track was dry and had sunshine, another at the same time was soaking wet and it was raining there. There were no radios in the days of the old Spa circuit, so drivers had no idea of circuit conditions and could encounter rain without warning, where there had been none on the previous lap. The nature of the circuit meant that cars spinning off could hit telegraph poles, houses, stone walls, embankments or trees. Many drivers were killed or seriously injured at Spa during the 1950s in all disciplines of motorsport that competed there.

1958 was won by Briton Tony Brooks, driving a Vanwall, from his teammate Stirling Moss. The race was not run in 1959, but 1960 was to be one of the darkest weekends in the history of Formula One. Grand Prix racing had moved forward to a new kind of car design – new British independent teams such as Cooper and Lotus had pioneered the rear-mid-engined car, much like the Auto Union Grand Prix cars of the 1930s. These cars were considerably lighter, faster and easier to drive than their front-engined predecessors, and it became obvious that rear-mid-engined cars were the way to go in purpose-built automobile racing. But this new type of cars had not been driven at Spa before, so no one knew how they would perform there. The high-speed bends at Spa were now much faster with these new cars – and in those days, the cars or circuits for that matter had absolutely no safety features of any kind. The cylinder-shaped bodywork was made of very thin highly flammable magnesium or fibreglass, and the tube-frame chassis of that day offered little crash resistance (as opposed to a modern-day monocoque, pioneered by Lotus only a few years later). Cars were not crash-tested and lacked roll bars (made mandatory in 1961) and fire extinguishers. Although drivers did wear helmets, they were made of weak and lightweight material and not scientifically designed or tested. Drivers in those days did not wear seatbelts – they found it preferable to be thrown from a car that might be on fire to reduce the chance of injury or death.

During practice, Stirling Moss, now driving a privately entered Lotus, had a wheel come off his car and he crashed heavily at the Burnenville right-hander. Moss, who was considered one of the best racing drivers in the world at the time, was thrown out of his car and landed unconscious in the middle of the track. The Englishman broke both legs, three vertebrae, several ribs and had many cuts and abrasions; he survived but did not race for most of that year. Briton Mike Taylor, also driving a Lotus, suffered a steering failure and crashed into trees next to the track near Stavelot. Taylor then was trapped in the car for some time with serious head and neck injuries. The accident ended his racing career; he later successfully sued Lotus founder Colin Chapman in British court for sale of faulty machinery. The race itself, however, was to be even more disastrous. On lap 17, Briton Chris Bristow, driving a Cooper, was fighting for sixth with Belgian Willy Mairesse. Bristow had never driven at Spa before, and was regarded as a brash and daring driver who had a reputation for being rather wild; the relatively inexperienced 22-year-old Englishman had been in many accidents during his short career. Mairesse was also known as an aggressive driver who had a win-at-all-costs mentality and was known to be difficult to pass, particularly on his home track- Bristow dueling with Mairesse on a very dangerous track he had never been to before meant that the young Englishman was in way over head at this circuit. Bristow and Mairesse touched wheels, and the Englishman lost control at Malmedy, overturned and crashed into an embankment on the right side of the track. The car rolled several times, Bristow was thrown from his car and was decapitated by some barbed-wire fencing next to the circuit, killing him instantly; his body partially landed on the track where it stayed for some time. Mairesse continued, but retired from the race later on with gearbox trouble. 5 laps later, 26-year-old Briton Alan Stacey, running in sixth place and driving a works Lotus, suffered a freak accident when he was hit in the face by a bird on the Masta straight not far from where Bristow had been killed. Stacey then lost control of his car at 140 mph (228 km/h) and it climbed up and flew off an embankment next to the track. After penetrating 10 feet of thick bushes, the car landed on a spot in a field some 25 feet lower than the track. On impact with the field, it then exploded and burst into flames, killing him. It was not known whether the impact broke his neck or if the fire burned him alive while unconscious. Australian Jack Brabham won the race, and British future great Jim Clark scored his first Formula One points by finishing 5th – but Clark, like a number of other drivers, developed an intense dislike for the circuit after he had to swerve at extreme speeds to avoid running over Bristow's headless body. It was the worst Formula One event in terms of fatalities until the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix.[4]

1961 saw Ferrari make use of their superior horsepower, and they romped home 1–2–3–4, with Phil Hill winning. 1962 saw Clark win his first race, going on to win the next three Belgian Grands Prix. 1963 was a rain-soaked race with Clark finishing 4.5 minutes in front of second-placed Bruce McLaren. 1966 featured cars built under new regulations with the engine capacity up to a maximum of 3 litres from 1.5 – engines had now twice as much horsepower as before. This year saw another rain-soaked race: on the first lap, as the field reached the far side of the circuit, a heavy rainstorm caused seven drivers to hydroplane off at Burnenville. Briton Jackie Stewart had a high speed accident at the Masta Kink, where he went through a woodcutter's hut, hit a telegraph pole, and dropped into a much lower part of the circuit where the car landed upside down. The BRM Stewart was driving had bent itself over his legs, so he could not get out by himself and the Scot ended up being stuck in his car for nearly 30 minutes. The fuel tanks, which were bags located inside the car that flanked the driver, had ruptured and were soaking him with flammable fuel, and he also had broken ribs and collarbone. Stewart's BRM teammate Graham Hill and Bob Bondurant, both of whom had gone off near Stewart, came to help. Because of the absence of safety precautions in those days, they had to borrow spanners from a nearby spectator, and the two drivers got Stewart out. There were other bad accidents on the circuit; some of the cars were hanging off 30-feet-high ledges.[citation needed] Stewart's crash at this race inspired his subsequent crusade for safety at racetracks. There was so much water on the track that the Climax engine in Clark's Lotus was flooded and failed. Briton John Surtees won the race in a Ferrari, followed by Austrian Jochen Rindt in a Cooper.

1967 saw American Dan Gurney in his Eagle win after Clark had mechanical problems – it was to be Eagle's only F1 victory. Briton Mike Parkes crashed heavily at 150 mph at Blanchimont after slipping on some oil that had dropped off of Jackie Stewart's BRM. After his car hit and climbed up an embankment, the works Ferrari driver was thrown out of his car, receiving serious leg and head injuries. He was in a coma for a week, and initially his legs were in danger of needing amputation. He survived, but never raced in Formula One again. 1968 saw a number of firsts: wings as an aerodynamic device were introduced for the first time in Formula One. The European constructors, particularly Colin Chapman and Mauro Forghieri, were influenced by American Jim Hall's Chaparral 2E and 2F sports cars' very large high strutted wings. New Zealander Chris Amon qualified his rear-wing equipped Ferrari on pole position by 4 seconds over Stewart in a Matra. Come race day, McLaren won their first ever victory as a constructor, with its founder Bruce McLaren winning – but the race saw yet another serious accident. Briton Brian Redman crashed his works Cooper heavily at high speed into a parked Ford Cortina road car at Burnenville, and the Cooper caught fire. He was seriously burned and also badly broke his right arm; he did not race for most of that year.

The following season, safety issues came to a head. Average lap speeds were past 150 mph (240 km/h), but the circuit still had virtually no safety features and as a result the race over the years was becoming less and less popular with the drivers. The Grand Prix was scheduled for 8 June 1969 as part of that year's season. When Jackie Stewart visited the circuit on behalf of the Grand Prix Drivers' Association he demanded many improvements to safety barriers and road surfaces, in order to make the track safe for racing.[5] When the track owners did not want to pay for the safety improvements, the British, French and Italian teams withdrew from the event, and it was cancelled in early April. The exclusion of the Belgian Grand Prix that year was not popular with the press, particularly British journalist Denis Jenkinson.[6] One last race was held there in 1970 with barriers and a temporary chicane at the fast Malmedy corner installed at the circuit, but even this did not stop the cars still averaging over 150 miles per hour (240 km/h) around the 8.7 miles (14.0 km) track. The race was won by Mexican Pedro Rodriguez in a BRM with New Zealander Chris Amon finishing 1.1 seconds behind in a March. But Spa was still too fast and too dangerous, and in 1971 the Belgian Grand Prix was cancelled, as the track was not up to mandatory FIA-mandated safety specs that year. The event was then eventually relocated.

Zolder and Nivelles

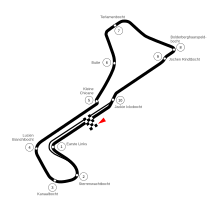

Following that decision, the Belgians decided to alternate their Grand Prix between Zolder in northern Belgium and a circuit at Nivelles-Baulers near Brussels. The first race at Nivelles in 1972 was won by Emerson Fittipaldi. Zolder hosted the race the following year and it was won by Jackie Stewart. Formula One returned to Nivelles in 1974. Once again the race was won by Fittipaldi, but the circuit was unpopular among the Formula One circus and after that event the organizers were unable to sustain a Grand Prix at Nivelles, and the track faded from the racing scene.

The Belgian Grand Prix would be held at Zolder a further nine times. Niki Lauda scored back-to-back victories at the track in 1975 and 1976, and in 1977 Gunnar Nilsson scored his only F1 victory at Zolder. The following year Mario Andretti dominated the race for Lotus, driving the 79 in its debut race. In 1979, Jody Scheckter won the race in his Ferrari, and in 1980 Didier Pironi became a first time winner in his Ligier.

The 1981 meeting was a chaotic event wrapped in the midst of the FISA–FOCA war and the poor conditions of the Zolder circuit, including its very narrow pitlane. During Friday practice, Osella mechanic Giovanni Amadeo was accidentally run over in the pitlane by Argentine Carlos Reutemann. He died of his injuries the day after the race. On race day, as a result of the poor conditions of Zolder and the accident on Friday, there was drivers' strike which caused the race to be started later than scheduled. Then, when the race started after yet another delay, there was a starting-grid accident involving an Arrows mechanic: Riccardo Patrese stalled his Arrows on the grid, so his mechanic Dave Luckett jumped onto the circuit to try and start Patrese's car; however, the organizers started the race and the whole field went into motion while Luckett was still on the road. Next, the other Arrows driver, Italian Siegfried Stohr, hit the back of Patrese's car, where Luckett was standing. Luckett was knocked unconscious and laid sprawled on the circuit. Then, when the field reached the pit straight again (by which time Luckett had been removed from the road, although the track still had Stohr's broken Arrows car on the circuit and the surface was littered with debris) a number of track marshals jumped onto the tarmac and frantically waved their arms to try to make the field stop while waving yellow flags instead of red flags. The cars went by at full racing speeds. When they came back again for the third lap they voluntarily stopped themselves. The race was restarted and was won by Reutemann. Luckett survived the incident, but neither Patrese nor Stohr started the second race.

Gilles Villeneuve died during practice at Zolder in 1982 after a collision with West German Jochen Mass going into the fast Butte corner. Villeneuve's Ferrari flipped a number of times and the Canadian was thrown out of his car during the accident; he was severely injured and died during the night at a hospital near the circuit. John Watson won the race for McLaren.

Return to Spa-Francorchamps

Spa-Francorchamps had been shortened to 4.3 mi (7 km) in 1979; the parts that went into and through the urban countryside that swept past towns and other obstructions had been cut out and replaced with a new series of corners right before the Les Combes left-hand corner, and the new track rejoined the old on the straight leading up to Blanchimont. The first race at the shortened Spa circuit was won by Frenchman Alain Prost, and the circuit was an immediate hit with drivers, teams and fans.

The Belgian Grand Prix returned to Zolder in 1984 and this was the last F1 race held at the Flemish circuit with Italian Michele Alboreto taking victory in a Ferrari.

1985 saw the event postponed because of a new asphalt that had been laid down specifically to help the cars on the often rain-soaked Spa circuit. But to the embarrassment of the organizers, the weather was hot, and the track surface broke up so badly the drivers could not drive on it. The event was moved from its original date in early June to mid-September. When mid-September came around, Brazilian Ayrton Senna took his first of five Belgian Grands Prix in a wet/dry race, driving a Lotus. Nigel Mansell dominated the 1986 event, and he and Senna took each other out the following year when Mansell attempted to pass the Brazilian on the outside of a wide corner. Senna won the next four Belgian Grands Prix, the first two being rain-soaked events. The 1988 event was the first Belgian Grand Prix to be held in late August/early September instead of May or June (excluding the rescheduled 1985 event) and it has remained in this time frame ever since. The 1990 event had to be restarted twice after a multi-car accident at the La Source hairpin on the first start and then Paolo Barilla crashing at Eau Rouge on the second start. In 1992 German Michael Schumacher won his first of 91 Grand Prix victories in a Benetton, a year after making his Formula 1 debut at the circuit. Damon Hill won the 1993 event after battling with Senna and Schumacher.

1994 saw a chicane installed at the bottom of Eau Rouge in response to the deaths of Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger at Imola that year. 1995 saw the chicane gone, and Schumacher won this and the next two Belgian Grand Prix. The 1998 event ran in torrential conditions. The race was originally stopped after an accident involving thirteen of the twenty-two runners at the first corner. After the restart, heavy rain caused low visibility, and Michael Schumacher ran into the back of David Coulthard, an event that angered Schumacher so much he stormed into the McLaren garage to confront Coulthard, claiming he had tried to kill him. Coulthard later admitted he had been at fault, due to his own inexperience.[7] Only eight drivers were classified finishers (two of whom were five laps behind, one of whom was Coulthard) and Damon Hill secured a victory ahead of his teammate Ralf Schumacher to record the Jordan team's first Formula One win.

Schumacher won his 52nd Grand Prix at Spa in 2001, surpassing Alain Prost's all-time record of 51 wins. Schumacher also won his seventh World Drivers' Championship title at Spa in 2004. There was no Belgian Grand Prix in 2003 because of the country's tobacco advertising laws. In 2006, the FIA announced the Belgian Grand Prix would not be on the calendar, since the local authorities would not be able to complete major repair work at Spa-Francorchamps before the September race.[8] The Belgian Grand Prix returned in 2007, when Kimi Räikkönen took pole position and his third Belgian Grand Prix win in a row.

In 2008, McLaren's Lewis Hamilton survived a frantic last two laps in a late shower of rain to win the race. Hamilton lost the lead to Ferrari's Kimi Räikkönen with an early spin but fought back in the closing laps to re-take the lead with two laps to go. On a soaking track, Hamilton passed Räikkönen, lost the lead again with a spin, re-took it and then saw Räikkönen crash. Ferrari's Felipe Massa took second leaving him eight points behind Hamilton. However, the stewards decided after the race to apply a 25-second penalty, considered a drive-through penalty under the regulations, for Hamilton's pass on Räikkönen after they had deemed that Hamilton had cut a corner in the Bus Stop chicane. This left Hamilton in third place behind Ferrari's Felipe Massa and BMW Sauber's Nick Heidfeld. The penalty cut Hamilton's lead over Massa to just two points with five races remaining. McLaren appealed the decision but were turned down as it is not permissible to appeal drive-through penalties. The stewards' decision was criticised by former world champion Niki Lauda calling it "completely wrong".[9]

In 2009, Bernie Ecclestone said in an interview that he would like the Belgian Grand Prix to rotate with a Grand Prix at the Nürburgring, rather than the Nürburgring rotating with the Hockenheimring.[10] This rotation never eventualised and as of June 2020[update] the Belgian Grand Prix is contracted to be held through 2022.[11]

The 2021 race became particularly notable for becoming the shortest Formula One World Championship race in history and the only World Championship Grand Prix not to have any running under full green flag conditions in its duration with only two full completed laps completed behind the safety car before the race was red-flagged on lap 3 and not restarted due to adverse weather conditions with the race classification being counted back to the end of lap 1 with Max Verstappen classified first, George Russell second and Lewis Hamilton third, with half points being awarded.[12] The controversy surrounding the awarding of points for this race led to Formula One and the FIA changing the points structure for shortened races ahead of the 2022 Formula One World Championship.[13][14] The 2022 race was won by Verstappen from 14th, the second lowest position the race has been won from, after Michael Schumacher in 1995.[15] The race's contract was extended to the 2023 season.[16] In October 2023 the race's contract was extended to the 2025 season.[17]

Winners

Repeat winners (drivers)

Drivers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

Michael Schumacher won the Belgian Grand Prix six times and Ayrton Senna won five times, including four consecutively from 1988 to 1991. Kimi Räikkönen, Lewis Hamilton and Jim Clark won four times (Clark also won four times in row in 1962–1965).

| Wins | Driver | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1992, 1995, 1996, 1997, 2001, 2002 | |

| 5 | 1985, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991 | |

| 4 | 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965 | |

| 2004, 2005, 2007, 2009 | ||

| 2010, 2015, 2017, 2020 | ||

| 3 | 1950, 1954, 1955 | |

| 1993, 1994, 1998 | ||

| 2011, 2013, 2018 | ||

| 2021, 2022, 2023 | ||

| 2 | 1952, 1953 | |

| 1972, 1974 | ||

| 1975, 1976 | ||

| 1983, 1987 | ||

| Source:[18] | ||

Repeat winners (constructors)

Teams in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

| Wins | Constructor | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 18 | 1952, 1953, 1956, 1961, 1966, 1975, 1976, 1979, 1984, 1996, 1997, 2001, 2002, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2018, 2019 | |

| 14 | 1968, 1974, 1982, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1999, 2000, 2004, 2005, 2010, 2012 | |

| 8 | 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1972, 1977, 1978, 1985 | |

| 7 | 1935, 1939, 1955, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2020 | |

| 6 | 2011, 2013, 2014, 2021, 2022, 2023 | |

| 4 | 1925, 1947, 1950, 1951 | |

| 1981, 1986, 1993, 1994 | ||

| 3 | 1930, 1931, 1934 | |

| 2 | 1933, 1954 | |

| 1992, 1995 | ||

| Sources:[18][19] | ||

Repeat winners (engine manufacturers)

Manufacturers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

| Wins | Manufacturer | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 18 | 1952, 1953, 1956, 1961, 1966, 1975, 1976, 1979, 1984, 1996, 1997, 2001, 2002, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2018, 2019 | |

| 13 | 1935, 1939, 1955, 1999, 2000, 2004, 2005, 2010, 2012, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2020 | |

| 10 | 1968, 1972, 1973, 1974, 1977, 1978, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1992 | |

| 8 | 1983, 1985, 1993, 1994, 1995, 2011, 2013, 2014 | |

| 6 | 1986, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991, 2021 | |

| 5 | 1960, 1962, 1963, 1964, 1965 | |

| 4 | 1925, 1947, 1950, 1951 | |

| 3 | 1930, 1931, 1934 | |

| 2 | 1933, 1954 | |

| Sources:[18][19] | ||

* Built by Cosworth, funded by Ford

** Between 1999 and 2005 built by Ilmor, funded by Mercedes

By year

A pink background indicates an event which was not part of the Formula One World Championship.

A yellow background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war European Championship.

A green background indicates an event which was part of the pre-war World Manufacturers' Championship.

Notes

- ^ Max Verstappen set the fastest time in qualifying, but he received a five-place grid penalty for a new gearbox driveline.[1] Charles Leclerc was promoted to pole position in his place.[2]

References

- ^ "Verstappen takes five-place grid penalty at Belgian GP for gearbox change". Formula 1.com. 28 July 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ "Penalty-hit Verstappen fastest in Belgian GP qualifying as Leclerc set to start from pole". Formula 1.com. 28 July 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ Liesemeijer, Herman. "Eau Rouge or Raidillon?". Archived from the original on 31 March 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ Tragic day overshadows Jack Brabham victory | Formula 1 | Formula 1 news, live F1 | ESPN F1 Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. En.espnf1.com (19 June 1960). Retrieved on 17 December 2013.

- ^ "Need for safer circuit", The Times, 25 March 1969, p. 14.

- ^ "Belgian GP succumbs to ban", The Times, 12 April 1969, p. 11

- ^ Crash was my fault, Coulthard admits Archived 23 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine. smh.com.au (7 July 2003). Retrieved on 17 December 2013.

- ^ "Belgian GP officially off the 2006 calendar". Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- ^ Lauda unhappy with Hamilton penalty Archived 13 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine. BBC Sport, 8 September 2008

- ^ Beurtrol voor GP F1 België kan pas in 2013. Sporza.be. 4 August 2009

- ^ Horton, Phillip (5 June 2020). "Renewed terms gives Spa-Francorchamps 2022 F1 deal". Motorsport Week. Motorsport Media Services. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ Benson, Andrew. "Max Verstappen declared winner of aborted rain-hit Belgian Grand Prix". BBC Online. BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ "F1 Commission approves changes to Sporting Regulations regarding points for shortened races". formula1. 14 February 2022. Archived from the original on 17 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "FIA make changes to Safety Car rules ahead of 2022 F1 season start". Formula1. 16 March 2022. Archived from the original on 16 March 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "Verstappen cruises to Belgian Grand Prix victory from P14 as Perez completes Red Bull 1-2". www.formula1.com. Formula One. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "Spa to form part of the 2023 F1 calendar following agreement to extend partnership". www.formula1.com. Formula One. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "Formula 1 to race in Belgium until 2025 under new deal". Formula 1. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Belgian GP". ChicaneF1. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Higham, Peter (1995). "Belgian Grand Prix". The Guinness Guide to International Motor Racing. London, England: Motorbooks International. pp. 353–354. ISBN 978-0-7603-0152-4 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "GP Belgium – Sports 4500 cc or 2250 cc s/c 1946 – Race Results". Racing Sports Cars. Archived from the original on 10 December 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2021.