Westward Ho! (novel)

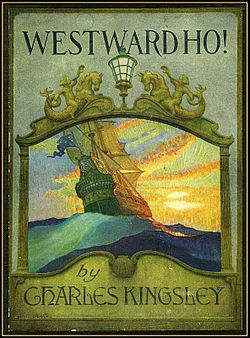

Cover of an 1899 edition by Frederick Warne & Co | |

| Author | Charles Kingsley |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Adventure fiction |

Publication date | 1855 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Pages | 378 |

| ISBN | 1500778745 |

| OCLC | 219787413 |

| Text | Westward, Ho! at Wikisource |

Westward Ho! is an 1855 historical novel written by British author Charles Kingsley.

Plot

Set initially in Bideford in North Devon during the reign of Elizabeth I, Westward Ho! follows the adventures of Amyas Leigh, an unruly child who as a young man follows Francis Drake to sea. Amyas loves local beauty Rose Salterne, as does nearly everyone else; much of the novel involves Rose's elopement with a Spaniard.

Amyas spends time in the Caribbean coasts of Venezuela seeking gold, and in the process finds his true love, the beautiful Indian maiden Ayacanora. During the return journey to England, he discovers that Rose and his brother Frank have been burnt at the stake by the Spanish Inquisition. He vows revenge on all Spaniards, and joins in the defence of England against the Spanish Armada. When he is permanently blinded by a freak bolt of lightning at sea, he accepts this as God's judgement and finds peace in forgiveness.

Title

The title of the book derives from the traditional call of boat-taxis on the River Thames, which would call "Eastward ho!" and "Westward ho!" to show their destination.[1][2] "Ho!" is an interjection or a call to attract passengers, without a specific meaning besides "hey!" or "come!"[3] The title is also a nod towards the play Westward Ho!, written by John Webster and Thomas Dekker in 1604, which satirised the perils of the westward expansion of London.[1] The full title of Kingsley's novel is Westward Ho! Or The Voyages and Adventures of Sir Amyas Leigh, Knight of Burrough, in the County of Devon, in the reign of Her Most Glorious Majesty, Queen Elizabeth, Rendered into Modern English by Charles Kingsley. This elaborate title is intended to reflect the mock-Elizabethan style of the novel.[4] Viola's use of "Westward ho!" in William Shakespeare's Twelfth Night is an earlier reference.

Kingsley dedicated the novel to Sir James Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak, and Bishop George Selwyn, whom he saw as modern representatives of the heroic values of the privateers who were active during the Elizabethan era.

Themes

Westward Ho! is an historical novel which celebrates England's victories over Spain in the Elizabethan era.

Although originally a political radical, Kingsley had by the 1850s become increasingly conservative and a strong supporter of overseas expansion.[4] The novel consistently emphasises the superiority of English values over those of the "decadent Spanish".[1] Although originally written for adults, its mixture of patriotism, sentiment, and romance caused it to be deemed suitable for children, and it became a firm favourite of children's literature.[5]

A prominent theme of the novel is the 16th-century fear of Catholic domination,[5] and this reflects Kingsley's own dislike of Catholicism.[4] The novel repeatedly shows the Protestant English correcting the worst excesses of the Spanish Jesuits and the Inquisition.[4]

The novel's virulent anti-Catholicism, as well as its racially insensitive depictions of the South Americans, has made the novel less appealing to a modern audience, although it is still regarded by some as Kingsley's "liveliest, and most interesting novel."[6]

Adaptations

In April 1925, the book was the first novel to be adapted for radio by the BBC.[7] The first movie adaptation of the novel was a 1919 silent film, Westward Ho!, directed by Percy Nash.[8] A 1988 children's animated film, Westward Ho!, produced by Burbank Films Australia, was loosely based on Kingsley's novel.[9]

Legacy

The book is the inspiration behind the unusual name of the village of Westward Ho! in Devon, the only place name in the United Kingdom that contains an exclamation mark.[10]

J. G. Ballard, in an interview with Vanora Bennett, claimed that being forced to copy lines from the novel as a punishment at the age of eight or nine was the moment he realised he would become a writer.[11]

References

- ^ a b c John Kucich, Jenny Bourne Taylor, (2011), The Oxford History of the Novel in English: Volume 3, page 390. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199560617

- ^ Samuel Schoenbaum (1987). William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life. Oxford University Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-19-505161-2.

- ^ Hodges, C. Walter (1979). The Battlement Garden: Britain from the Wars of the Roses to the Age of Shakespeare (1st American ed.). New York: Houghton. p. 116. ISBN 9780816430048.

- ^ a b c d Mary Virginia Brackett, (2006), The Facts on File companion to the British novel. Vol. 1, page 477. ISBN 081605133X

- ^ a b Ian Ousby, (1996), The Cambridge Paperback Guide to Literature in English, page 418. Cambridge University PressISBN 0521436273

- ^ Nick Rennison, (2009), 100 Must-read Historical Novels, page 80. A&C Black. ISBN 1408113961

- ^ Briggs, Asa. The BBC: The First Fifty Years. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985. p. 63.

- ^ Westward Ho! (1919) at IMDb

- ^ Westward Ho! (TV 1988) at IMDb

- ^ A Wild West country walk | England – The Times 11 Feb 2007. ("Westward Ho! is an invigorating starting point, because it's the only place in the British Isles with an exclamation mark.")

- ^ J.G. Ballard, The Unlimited Dream Company (London: Harper, 2008), pp.2-6 (p.2).

External links

The full text of Westward Ho! at Wikisource

The full text of Westward Ho! at Wikisource Media related to Westward Ho! (novel) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Westward Ho! (novel) at Wikimedia Commons