User:UndercoverClassicist/Alfred Biliotti

Sir Alfred Biliotti | |

|---|---|

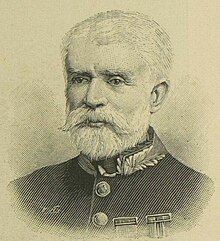

Portrayed in the Illustrated London News, 1897 | |

| Born | 14 July 1833 |

| Died | 1 February 1915 (aged 81) |

| Citizenship | British (from 1871) |

| Spouse |

Marguerite (m. 1889) |

| Children | 1 (Emile) |

| Awards |

|

Sir Alfred Biliotti KCMG CB (14 July 1833 – 1 February 1915) was a Levantine Italian, born on Rhodes, who became a British consular official and amateur archaeologist.

Early life

Alfred Biliotti was born on 14 July 1833 in a Catholic family in Rhodes, capital of the eponymous island.[1] His father, Charles Biliotti, was a native of Livorno, then in the Italian Grand Duchy of Tuscany; his mother, Honorine (née Fleurat), was the daughter of George Fleurat, the French Vice-Consul on the island of Rhodes,[2] then a loosely-controlled part of the Ottoman Empire.[3] Charles Biliotti had moved to Rhodes at some point before the 1820s, possibly during or in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars,[4] and married Honorine in the 1830s. Alfred was the eldest of their seven children; by the time of his birth, Charles Biliotti was a merchant on Rhodes who had worked for four years as an unpaid translator for the British consular service on the island.[2] Charles Biliotti stopped his work for the British around the time of Alfred's birth, though continued to perform sporadic consular work for the governments of Spain and Tuscany.[5] Charles's brother Fortunato also served as a British consular agent, on the island of Kastellorizo.[6]

The elder Biliotti's business included work and property in the town of Makri, in the southwestern part of mainland Turkey.[5] On 7 November 1845, Lawrence Jones, a British baronet, was robbed and murdered by brigands near the town; after both the British consulate and the Ottoman government failed to find those responsible, Charles Biliotti worked with Ali Pasha, the kaymakam (district governor) of Makri, to catch them; they were arrested on 23 April 1846.[a] Following Ali Pasha's murder by relatives of the arrested men, Biliotti was forced to leave Makri and to abandon his business interests in the town; however, the affair reaffirmed the relationship between him and the British state, and he returned under British protection to Makri in March 1848 as Britain's vice-consul.[6]

Alfred Biliotti was a Levantine Italian; a member of the Italian diaspora settled in the eastern Aegean.[7] He may have been educated at a Christian school, possibly in the Ionian town of Ayvalık, but his biographer David Barchard considers it more likely that he never received any formal education, except via a tutor. He appears to have been taught French and a little English, and to have received the equivalent of a secondary school–level education.[8]

Diplomatic career

Early career

In 1849, at the age of sixteen, Biliotti took a post as a clerk to his father, the British vice-consul based at Makri.[9] In 1850, he was made a dragoman (interpreter)[b] at the British consulate on Rhodes; he is recorded from 1853 as making certified translations for the consulate from Greek into English.[8]

Biliotti first met Charles Newton, an archaeologist then working for the Foreign Service, during the latter's posting to the eastern Aegean. In the spring of 1852, Newton was posted as a vice-consul to Mytilene on the island of Lesbos, though the consulate at Rhodes was instructed to facilitate Newton's archaeological work as a greater priority than any diplomatic duties of his role. Newton's main task was to find archaeological finds and acquire them for British museum collections, and to identify local agents to supervise exploratory excavations. In 1853, he was promoted to the role of consul on Rhodes.[12] In June of the same year, he travelled to the island of Chios with the historian George Finlay and Biliotti, then aged nineteen.[13] Barchard credits Newton's patronage of Biliotti with allowing the latter to advance to prominence in the consular service, despite his lack of educational qualifications.[14]

On 24 January 1856,[15] Biliotti became vice-consul on Rhodes. The position was unpaid,[16] as were most other British consular posts: they were generally assumed to be part-time positions whose holders would support themselves by other commercial activities.[2] From 15 February until 12 April 1860, and again from 15 February to 12 April 1861, he held the position of acting consul. He was taken on as a paid vice-consul on 26 August 1863.[17] He became a naturalised British citizen on 23 October 1871.[18]

In 1873 or 1874, Biliotti was made vice-consul at Trebizond: the historian Lucia Patrizio Gunning has written that this move was intended to facilitate his archaeological work at the nearby site of Satala.[20] Though his predecessor, Gifford Palgrave, had held the post of consul, Biliotti was kept at the lower rank of vice-consul and paid £200 per year (equivalent to £23,454 in 2023) less in annual salary.[21] In November 1878, following an intimation from the Foreign Secretary, Lord Salisbury, that he was considering transferring Biliotti to Diyarbakir in eastern Turkey, Biliotti wrote in protest to Austen Henry Layard, the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, and successfully did away with the proposal.[22] Biliotti was promoted to consul in 1879;[23] his father died at the end of May in the same year, and Biliotti wrote repeatedly to Salisbury to request a transfer to Crete. This request was not yet granted,[24] though Biliotti was given additional responsibility for the consulate at Sivas in 1882.[23] He was, however, paid less than other British consular officials and the representatives of other powers in Trebizond: in 1881, Biliotti received £400 per year (equivalent to £50,968 in 2023) and £160 (equivalent to £20,387 in 2023) in expenses, while his predecessor had been paid £600 per year and £200 in expenses in 1871 and his French counterpart was paid £1,250 (equivalent to £159,274 in 2023) per year.[23]

Crete

In the midst of the strife

And war to the knife

O'er a question fierce and knotty

Let us sing to the praise

'Mid the death-strewn maze

Of Sir Alfred Biliotti

No craven was he

Who could put to sea

Saving thousands by pluck and daring

Let King George have his say

But we'll cheer the way

Of our consul's overbearing!

In 1885, Biliotti succeeded Thomas Backhouse Sandwith as Consul on Crete, based at Chania. He was made Consul-General on the island in 1897.[26] In 1900, the French diplomat and philhellene Victor Bérard alleged that Biliotti's appointment to the post in Chania had been a reward for his "obscure but useful" services in acquiring antiquities for the British Museum.[27] According to Biliotti's successor, Esmé Howard, Biliotti ended a problem of huge numbers of frivilous lawsuits raised by the island's Maltese community by requiring parties to a case to place money in deposit before it could be heard.[29]

The Cretan consulate was, in common with the consular delegations of most other Great Powers, marked by infighting and ineffective co-operation.[30]

The consuls of other nations accused Biliotti of supporting anti-Ottoman rebellion and fomenting his own secret plots; he in turn accused them of working against him.[30]

The collapse of the Pact of Halepa, 1889

Since 1878, Crete had been administered according to the Pact of Halepa, which had been negotiated by the Ottoman Empire with Greek rebels on the island.[31] Under the Pact, Crete was treated as a semi-autonomous province,[32] and Christians were given a privileged position: they were granted preferential treatment in applying for official posts, a guaranteed majority in the island's governing assembly, and the right to found newspapers and intellectual societies, while Greek was also made an official language of the island.[33]

Following the legislative elections of April 1889, which were won by the reformist, liberal xypolitoi ('barefoot') party, the defeated conservative faction held demonstrations calling for union with Greece (enosis).[34] In response, the Ottoman government imposed martial law. In December, the Ottoman government abrogated the terms of the Pact of Halepa and reimposed direct rule,[35] under the governor Shakir Pasha.[36] The Cretan politician Eleftherios Venizelos, later Prime Minister of Greece, was a friend of Biliotti's and has sometimes been described as his protégé:[37] Venizelos fled Crete for mainland Greece around the end of September, fearing Ottoman reprisals; Biliotti may have lent him the rowing-boat he used in his escape.[38] In July 1889, the Ottomans stationed around 20,000 soldiers on the island. Cretan Christians protested, and accused the soldiers of various crimes and abuses of power; Biliotti and the other consuls largely found these accusations to be false. In the years that followed, the Christian population largely refused to co-operate with the Ottoman government, effectively making the island ungovernable.[39]

The Cretan Revolt of 1896

From 1895, violence between Crete's Christians and Muslims increased.[40] One insurrectionist, Manoussos Koundouros, who took up arms in September 1895, had previously been a mentee of Biliotti's; Biliotti had earlier encouraged the Ottoman governor to pay for Koundouros to be educated in Athens. The connection led the Ottoman state to hold Biliotti responsible for the outbreak of rebellion.[41]

On 24 May 1896, street fighting broke out in Chania on the Muslim festival of Eid al-Adha: Muslims from the countryside had gathered in the town, both for the celebration and to protect themselves from violence. By that evening, Christians and Muslims had erected barricades in the streets and began shooting at each other:[41] Biliotti requested that a warship of the Royal Navy be sent immediately to restore order. The fighting escalated into riots by bands of Muslims and further fighting in the surrounding countryside; in response, armed Christian volunteers crossed from the Greek mainland. Other nations' consuls made similar requests to their government for help, and a British-led coalition imposed a new constitution upon Crete in August 1896.[40]

Open rebellion broke out within a year.[36]

Following the proclamation of Cretan independence in February 1897, a Greek force landed on the island and a short-lived war broke out between Greece and the Ottoman Empire, which ended with a Greek defeat in May.[42]

In December,[42] a joint British, French, Russian and Italian force occupied Crete; the following year, they appointed Prince George of Greece and Denmark as High Commissioner, effectively ending Ottoman control of the island.[43]

During the unrest, Biliotti's colleagues accused him of conspiring to assist the Cretan rebels fighting against Ottoman rule; he in turn wrote in 1896 to Lord Salisbury, the Prime Minister, accusing them of undermining his diplomatic work and of being unable to work effectively together.[30] Biliotti was credited in Punch magazine with saving "by his personal exertions many thousand Moslem lives".[44]

Salonica

In March 1899, the Foreign Office decided to transfer Biliotti to Salonica in Thessaly, then an Ottoman possession, as Consul-General: a more prestigious post, albeit one that came with a salary £200 (equivalent to £28,437 in 2023) lower than he had received at Chania.[45]

During Biliotti's service in Salonica, it was a centre of Bulgarian unrest against the ruling Ottoman state. The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, a secret revolutionary society, had been founded in the city in 1893; in 1903, the IMRO began to collaborate with other revolutionary organisations towards a revolt against the Ottomans. Biliotti, sharing the views of other European and American diplomats in the city, wrote to the Foreign Office on 14 February that he considered the imminent rebellion to be a cynical attempt by the Bulgarians to generate a humanitarian crisis and so to provoke intervention by other European powers; he later wrote, on 25 February and 9 March, of his intention to warn the Ottoman governor of the uprising. The revolt, known as the Ilinden Uprising, eventually broke out in August.[46]

Archaeological work

Newton took on Biliotti as his protégé and trained him as an archaeologist from the time that the two men first met in the early 1850s.[48] In 1856, Biliotti conducted an impromptu excavation to rescue survivors from the Church of St John on Rhodes, which was destroyed on 6 November in an explosion after lightning struck gunpowder that had been stored in its cellars.[49] He never received formal archaeological education, apart from a period of three months in 1864, when he was funded by the British Museum to study archaeology and art history in Wiesbaden.[50]

Barchard judges that Biliotti's archaeological work was the main locus of interest in him for his British superiors until the mid-1860s, though this situation reversed towards the end of that decade.[50] Objects excavated by Biliotti form part of the collections of the British Museum,[51] and at least eleven objects in the Fitzwilliam Museum of the University of Cambridge have been traced to his excavations of cemeteries on Rhodes.[52] In total, the British Museum holds more than 3,000 objects excavated by Biliotti and his collaborator Auguste Salzmann from Rhodes.[51]

In 1869, Biliotti visited Crete for the first recorded time, as a representative of the British Museum, which sent him to Ierapetra on the island's south coast to acquire two Roman statues, one of which is now known as the Hieraptyna Hadrian. The Ottoman authorities, however, refused to allow the statues' export, and reserved them for the Imperial Ottoman Museum in Constantinople.[53] Between 1880 and 1883, by which point Biliotti had been reassigned to Trebizond, his brother Albert supervised on his behalf the excavation of over 500 tombs at the site of Kymissala on the south-western coast of the island.[54] He may have undertaken further archaeological work on Rhodes in 1885, during a visit of several months, shortly after his assignment to Chania, which had the ostensible purpose of seeing Biliotti's mother.[28]

During his time on Crete, Biliotti guided several British archaeologists around the island, including John Myres, who visited in the summer of 1893.[c] Biliotti attempted to secure for Myres a firman (permit) to excavate at the site of Knossos, but his request was denied by Mahmoud Pasha, the island's Ottoman governor, in December of that year.[56] He wished unsuccessfully to excavate at the site of Gortyn,[57] which was instead excavated from 1884 by what would later become the Italian School of Archaeology at Athens.[58] In 1896, he made a plan of the site of Ephesus, earlier excavated by Newton, and sent it to Gerard Noel, a British aristocrat and former member of parliament.[59]

Kameiros

In common with other archaeologists of his time, Biliotti had an interest in locating the three ancient cities of Rhodes – Kameiros, Ialysos and Lindos – known from ancient literary sources.[54] Charles Newton first suggested the possible location of Kameiros during his visit to Rhodes in 1853.[16] Biliotti wrote of his intention to locate the three cities in a letter to the British Museum on 27 June 1859.[54]

Biliotti and the French archaeologist Auguste Salzmann excavated at Kameiros from 1859 until 1864.[16] Their excavations included two votive deposits from the settlement's acropolis and a total of 310 graves,[11] of which 288 were burials of the archaic and classical periods in the Fikellura cemetery,[60] 18 were from the cemeteries at Paptislures and Kasviri, and 3 were from the cemetery at Kechraki.[11]

Biliotti and Salzmann were assisted in obtaining the necessary firman by Newton and the British Museum, to whom they sold many of their finds in exchange. The British Museum officially took charge of the excavations, engaging Biliotti and Salzmann as its agents, between October 1863 and June 1864.[16] Their finds were used by the museum to establish the chronological sequence of its ancient Greek terracotta and glass artefacts.[16]

Newton spent most of November 1863 on Rhodes, assisting with Biliotti's excavations. He was accompanied by his wife, the artist Mary Newton, and their friend Gertrude Jekyll; Biliotti sent Turkish men as models for their drawings.[61]

Newton used his influence as the British Museum's Keeper of Greek and Roman Antiquities to ensure that the project was able to continue until 1864.[54] In the museum's 1864 Parliamentary Report, he wrote that "the fruits of these excavations [at Kameiros] constitute some of the most important accessions which have been made for many years to the Department".[62]

The excavation of Kameiros was only sparsely published: summary reports were published as articles in Salzmann's name in 1861, 1863 and 1871, and a book of sixty plates of lithographic images was released, also in Salzmann's name, in 1875, three years after the latter's death.[63] In 1881, Biliotti's nephew, Eduard Biliotti, and a priest, Abbé Cotret, published some of the descriptions Biliotti had made of the the graves there.[64]

Bargyla

Between February and September 1865, Biliotti collaborated with Salzmann to conduct excavations in the area of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, near Bodrum in southwestern Turkey.[66] These followed earlier excavations by Newton in the same area;[67] Biliotti and Salzmann worked in plots of land which Newton had initially been unable to purchase for archaeological work.[65]

During the excavations, Biliotti became the first to document a tomb at Bargylia in the shape of the mythical Scylla. Biliotti collected fragments of its architecture and sculpture for the British Museum, and wrote an account of the monument and its condition. The location of the tomb was subsequently forgotten; when it was rediscovered in 1991, Geoffrey Waywell used Biliotti's notes to help form his reconstruction of the monument.[67]

Ialysos

Biliotti excavated on Ialysos on Rhodes on behalf of the British Museum in 1868 and 1870.[16]

His excavations here uncovered the first examples of Mycenaean painted pottery known to archaeological scholarship. The objects were bought by the polymath John Ruskin, who gave them to the British Museum: they were the first large group of Mycenaean artefacts to enter its collections.[69]

Although Biliotti's notes as to the stratigraphy of their find-spots would have allowed archaeologists to realise that they dated to the Late Bronze Age (c. 1200–1100 BCE), and so belonged to a hitherto-unknown prehistoric civilisation, the artefacts were incorrectly identified as belonging to the classical period and as being "oriental" works imported to Rhodes. They therefore received comparatively little scholarly attention until after the excavations of Heinrich Schliemann at Mycenae in 1876, during which Schliemann named the civilisation of Bronze Age Greece as "Mycenaean": it was then realised that the Ialysos finds belonged to the same culture.[69]

Satala

During his service at Trebizond, Biliotti visited the Turkish town of Saddak for nine days in September 1874.[70] The visit was prompted by the discovery there, in 1872, of fragmentary bronze statues including a head and hand of the goddess Aphrodite.[d][73] Newton tasked Biliotti with investigating the provenance of the Aphrodite statue, which had also been claimed as a find from Thessaly; Biliotti wrote two letters back to Newton, on 22 December 1873 and 4 March 1874, affirming that it had indeed been found at Saddak. Newton subsequently sent him to Saddakto ascertain whether any additional fragments of the statue or other works were to be found there,[74] and persuaded the Foreign Office to grant Biliotti the necessary time off from his duties and money to cover his expenses during the expedition.[72]

Biliotti's explorations at Saddak were hampered by poor weather, but he reported that local peasants had found fragments of other bronze statues in the area, and correctly asserted that it was the site of the ancient town of Satala,[75] the fortress of the Roman Legio XV Apollinaris.[70] Funded by £10 (equivalent to £1,173 in 2023) of Newton's own money, he made small-scale excavations with a team of 36 workers in the fields where the Aphrodite statue was reported to have been found, which turned up no further sculptural remains.[76] Biliotti correctly identified the basilica of the site, though contemporary archaeologists generally dismissed his interpretation and considered the building to be an aqueduct.[77] Although Biliotti instructed the locals to alert him of any further archaeological finds, none were forthcoming, and the British Museum decided against a full excavation of the site, believing the cost to be prohibitive and the ruling Ottoman Empire likely to impose difficulties upon the export of any finds to Britain.[78]

Biliotti made a report of his excavations to Frederick Stanley, the Financial Secretary to the War Office, on 24 September, but it was not published until 1974.[79] In that year, the archeologist Terence Mitford wrote that it "remains by far the best description of the legionary fortress" at Satala, partly because the site had deteriorated considerably in the century since Biliotti's visit.[e] According to Mitford, Biliotti's work was the only recorded archaeological excavation in the Roman frontier region of Lesser Armenia, or on the limes (frontier fortifications) between Trebizond and the Keban Dam.[19]

Çirişli Tepe

In 1883, Biliotti discovered the hilltop sanctuary of Çirişli Tepe, approximately 50 kilometres (31 miles) south of the ancient Greek city of Amisos on the Turkish coast of the Black Sea.[81] He collected objects from the surface around the remains of a rock-cult altar,[82] numbering around 680 votive terracotta figurines, 10 clay lamps and some other potsherds.[83] He also found a bilingual inscription in both Greek and Latin, recording a dedication to Apollo made in the 1st century CE by Casperius Alianus, a resident of Amisos. "Alianus" may have been Casperius Aelianus, who served as praetorian prefect to the emperors Domitian and Nerva.[84]

Biliotti initially kept the finds he discovered, but gave them to the British Museum in 1885. No formal study or archaeological publication of the finds was made until 2015.[82]

Later career, retirement and death

Biliotti retired in 1903.[85] As part of a wider reduction of its diplomatic corps in the Ottoman Empire, Britain closed its consular office in Rhodes in the same year.[86]

He died on 1 February 1915, leaving what Barchard describes as a "relatively modest" estate of £1,107 (equivalent to £112,049 in 2023).[86] He is buried, along with other members of his family, in the Catholic cemetery on Rhodes.[87]

Biliotti was the only member of his family to take British nationality; his son and grandchildren lived in Italy, with Italian nationality.[88]

Honours

Biliotti was made a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George in 1886, and a Companion of the Order of the Bath in 1890.[16] He was knighted in 1896 as a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George, on the orders of Lord Salisbury, giving him equal rank to the British ambassador – an unusual honour for a consular official in the period.[89]

In 1882, Biliotti was elected as an honorary member of the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies.[90]

Assessment, personal life and character

In 1889,[91] while stationed at Chania, Biliotti married Marguerite, a close relative of Paul Blanc, the French consul on the island.[92] They had one son, Emile, who moved the family to Italy and died there in the late 1930s.[93]

Reflecting on the Cretan crisis of 1897, Robert Hastings Harris, who had commanded the British naval forces in the theatre, called Biliotti "in every way the right man in the right place" for his knowledge of Mediterranean languages and customs.[94]

Biliotti's prominence seems to have been a source of bitterness for junior consular officials in Istanbul, who mocked his poor English by underlining the grammatical mistakes in his letters.[88]

Biliotti's consular reports have been widely used by historians and scholars of the Ottoman Empire.[95]

Michael Meeker describes Biliotti as "more an oriental than an orientalist".[96]

Michael Meeker has written that Biliotti developed an increasingly hostile view of Ottoman Muslims during his posting to Trebizond.[97] According to Meeker, Biliotti considered it essential for the stability of the region that its Orthodox Christian population, which was generally opposed to Britain's imperial rival Russia, should occupy a dominant position over its Muslim inhabitants, and exaggerated the size of the Orthodox population around Trebizond in his reports, in order to reinforce his argument.[98] Of an 1885 consular report, in which Biliotti described the distribution and cultural practices of the Muslim population in the east of his district, Meeker writes, "If Biliotti's superiors believed this ... they would believe anything".[99] During his time on Crete, Biliotti took a negative view of the island's Muslim population; when Robert Reinsch, a German tourist, was murdered in Crete in 1889, Biliotti erroneously and without evidence suggested that the crime had been the work of a Muslim secret society. Meanwhile, he adopted a credulous outlook towards Cretan Christians.[100]

Published works

- Biliotti, Alfred (10 November 1876). "The Recent Rising in Crete". The Times. p. 10.[90]

Footnotes

Explanatory notes

- ^ In thanks for his service, the family of Lawrence Jones presented Charles Biliotti with a silver jug and cup; Alfred Biliotti listed these as his foremost possessions in his own will.[6]

- ^ Keith Brown translates dragoman as "fixer".[10]

- ^ Myres had previously intended to visit in 1899, and sought Biliotti's advice following the revolt of the same year: Biliotti initially advised that it was safe to travel, but later warned Myres off a few days before he was due to depart.[55]

- ^ A false story later emerged that Biliotti had excavated the head and brought it to the British Museum; Biliotti did not in fact visit Satala until two years after its discovery.[71]

- ^ The archaeologist Christopher Lightfoot, who led his own survey at Satala, reaffirmed Mitford's judgement in 1998.[80]

References

- ^ Barchard 2006, pp. 7, 10; Kutbay 2014, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Barchard 2006, p. 7.

- ^ Barchard 2006, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 7. For the suggestion that Charles Biliotti moved during the Napoleonic Wars, see Kutbay 2014, p. 42.

- ^ a b Barchard 2006, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Barchard 2006, p. 9.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 8. On the term "Levantine Italian", see McGuire 2020, p. 93.

- ^ a b Barchard 2006, p. 10.

- ^ Gill 2004, p. 80; Barchard 2006, p. 10 (for Charles Biliotti as the Vice-Consul)

- ^ Brown 2013, p. 33.

- ^ a b c d Salmon 2019a, p. 98.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 11. According to Salmon, Newton held the consul's role in an acting capacity.[11]

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 12.

- ^ Hertslet 1865, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gill 2004, p. 80.

- ^ Hertslet 1865, p. 59.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 15; "Naturalisation Certificate: Alfred Biliotti". The National Archives. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ a b Mitford 1974, p. 221.

- ^ Gunning 2022, p. 226. Gill gives the year as 1873.[16]. Mitford writes that he was in post by the time of his arrival at Satala at the end of August 1874.[19]

- ^ Barchard 2006, pp. 15, 18.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Barchard 2006, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Barchard 2006, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Punch, 20 March 1897, p. 143. The author earlier noted George I's disapproval of Biliotti's 'overbearing' conduct.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 21. Gill gives the year as 1899.[16]

- ^ Bérard 1900, pp. 92–93; Barchard 2006, p. 13.

- ^ a b Barchard 2006, p. 21.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 21. Barchard suggests that this account may have been "consular folklore".[28]

- ^ a b c Rathberger 2010, p. 105.

- ^ Kaloudis 2019, p. 16.

- ^ Georgiadou 2003, p. 256.

- ^ MacGillivray 2000, p. 88; Mylonakis 2023, p. 99. For the terms of the Pact of Halepa, see Miller 1934, pp. 418–419.

- ^ Llewellyn-Smith 2021, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Llewellyn-Smith 2021, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b Mylonakis 2023, p. 99.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 23; Llewellyn-Smith 2021, p. 57.

- ^ Llewellyn-Smith 2021, p. 57.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 23.

- ^ a b Llewellyn-Smith 2021, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b Barchard 2006, p. 25.

- ^ a b Goldstein 2005, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Ferguson 2010, p. 174; Calic 2019, p. 321.

- ^ Punch, 20 March 1897, p. 143.

- ^ Barchard 2006, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Karakasidou 2002, p. 579.

- ^ Villing 2019, pp. 78–80.

- ^ Barchard 2006, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 13. For the church's destruction, see Setton 1984, p. 208 and Harwig 1875, p. 279.

- ^ a b Barchard 2006, p. 15.

- ^ a b Villing 2019, p. 72.

- ^ Gill 2023, p. 354.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d Salmon 2019b, p. 160.

- ^ Coutsinas 2006, p. 525.

- ^ Coutsinas 2006, pp. 525–526.

- ^ Gill 2004, pp. 80–81.

- ^ de Grummond 2015, p. 418.

- ^ Barchard 2006, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Gill 2004, p. 80; Salmon 2019a, p. 98.

- ^ Challis 2023, p. 394.

- ^ Salmon 2019a, p. 98. The "Department" mentioned is the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities, of which Newton was Keeper.[11]

- ^ Salmon 2019b, p. 157.

- ^ Salmon 2019b, pp. 157–158.

- ^ a b Higgs 1997, p. 30.

- ^ Gill 2004, p. 80. Higgs gives the beginning of the excavation as March.[65]

- ^ a b Jenkins 2006, p. 232.

- ^ "Kalathos". British Museum. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ a b Barchard 2006, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b Mitford 1974, pp. 221, 225.

- ^ Lightfoot 1998, p. 275; Gunning 2022, p. 225.

- ^ a b Gunning 2022, p. 225.

- ^ Lightfoot 1998, p. 274; Gunning 2022, p. 225. Lightfoot gives the date of the sculptures' discovery as 1873, which was the year that the British Museum first learned of their excavation. The head was in the collection of the antiquities dealer Alessandro Castellani by October 1872, when he mentioned it in a letter.[72]

- ^ Gunning 2022, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Gunning 2022, p. 226.

- ^ Mitford 1974, p. 236.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Gunning 2022, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Mitford 1974, p. 225. For Stanley's position, see Matthew 2004.

- ^ Lightfoot 1998, p. 274.

- ^ Summerer 2015, pp. 572–573.

- ^ a b Summerer 2015, p. 573.

- ^ Summerer 2015, pp. 574–575.

- ^ Summerer 2015, p. 574.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 5.

- ^ a b Barchard 2006, p. 52.

- ^ "Rhodes Cemetery". Levantine Heritage. Archived from the original on 28 February 2024. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ a b Barchard 2006, p. 6.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 5, 25–26.

- ^ a b Gill 2004, p. 81.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 20; "Biliotti, Alfred". Who Was Who. Vol. 2 (4th ed.). London: Adam and Charles Black. 1967 [1929]. p. 92. OCLC 1036935913 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 20.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 53.

- ^ Quoted in Llewellyn-Smith 2021, p. 93. For Harris's role in the Cretan Revolt, see Plarr 1899, p. 482.

- ^ Kutbay 2014, p. 42.

- ^ Meeker 2010, p. 318.

- ^ Meeker 2010, n. 33, pp. 319–320; Barchard 2006, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Meeker 2010, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Meeker 2010, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Barchard 2006, p. 24.

Works cited

- Barchard, David (2006). "The Fearless and Self-reliant Servant: The Life and Career of Sir Alfred Biliotti (1833–1915), an Italian Levantine in British Service" (PDF). Studi Miceni ed Egeo-Anatolici. 48: 5–53. ISSN 1126-6651. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Bérard, Victor (1900) [1898]. Les affaires de Crète [The Affairs of Crete] (in French) (2nd ed.). Paris: Armand Colin et Cie. OCLC 23409521.

- Brown, Keith (2013). Loyal Unto Death: Trust and Terror in Revolutionary Macedonia. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253008473.

- Calic, Marie-Janine (2019). The Great Cauldron: A History of Southeastern Europe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674983922.

- Challis, Debbie (2023). "The Ghosts of Ann Mary Severn Newton: Grief, an Imagined Life and (Auto)biography". In Lewis, Clare; Moshenska, Gabriel (eds.). Life-Writing in the History of Archaeology: Critical Perspectives. London: UCL Press. pp. 379–404. ISBN 9781800084506 – via Google Books.

- "Consule Biliotti". Punch. Vol. 112. 20 March 1897. p. 143. Retrieved 2 May 2024 – via Google Books.

- Coutsinas, Nadia (2006). "À la conquête de Cnossos: archéologie et nationalismes en Crète 1878–1900" [To the Conquest of Knossos: Archaeology and Nationalisms in Crete, 1878–1900]. European Review of History: Revue européenne d'histoire (in French). 13 (4): 515–532. doi:10.1080/13507480601049187.

- De Grummond, Nancy Thomson (11 May 2015). Encyclopedia of the History of Classical Archaeology. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-26861-0.

- Ferguson, Michael (2010). "Enslaved and Emancipated Africans on Crete". In Cuno, Kenneth M.; Walz, Terence (eds.). Race and Slavery in the Middle East: Histories of Trans-Saharan Africans in Nineteenth-century Egypt, Sudan, and the Ottoman Mediterranean. Cairo and New York: American University in Cairo Press. pp. 171–196. ISBN 9789774163982.

- Georgiadou, Maria (2003). "Expert Knowledge between Tradition and Reform: The Carathéodorys: A Neo-Phanariot Family in 19th Century Constantinople". In Anastassiadou-Dumont, Méropi (ed.). Médecins et ingénieurs ottomans à l'âge des nationalismes [Ottoman Doctors and Engineers in the Age of Nationalisms]. Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose. pp. 243–293. ISBN 2706817623.

- Gill, David (2004). "Biliotti, Alfred". In Todd, Robert B. (ed.). The Dictionary of British Classicists. Vol. 1. Bristol: Thoemmes Continuum. pp. 80–81. ISBN 1855069970.

- Gill, David (2023). "Archaeologists, Collectors, Curators and Donors: Reflecting on the Past Through Archaeological Lives". In Lewis, Clare; Moshenska, Gabriel (eds.). Life-Writing in the History of Archaeology: Critical Perspectives. London: UCL Press. pp. 353–378. ISBN 9781800084506 – via Google Books.

- Goldstein, Erik (2005). Wars and Peace Treaties: 1816–1991. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 1134899122.

- Gunning, Lucia Patrizio (2022). "Cultural Diplomacy in the Acquisition of the Head of the Satala Aphrodite for the British Museum". Journal of the History of Collections. 34 (2): 219–231. doi:10.1093/jhc/fhab025.

- Harwig, Georg (1875). The Aerial World: A Popular Account of the Life and Phenomena of the Atmosphere. New York: D. Appleton. OCLC 2208210 – via Internet Archive.

- Hertslet, Edward (1865). The Foreign Office List, Forming a Complete British Diplomatic and Consular Handbook. London: Harrison. OCLC 162820942. Retrieved 2 May 2024 – via Google Books.

- Higgs, Peter (1997). "A Newly Found Fragment of Free-Standing Sculpture from the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus". In Jenkins, Ian; Waywell, Geoffrey B. (eds.). Sculptors and Sculpture of Caria and the Dodecanese. London: British Museum Press. pp. 30–35. ISBN 0714122122.

- Jenkins, Ian (2006). Greek Architecture and Its Sculpture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674023888.

- Kaloudis, George (2019). Navigating Turbulent Waters: Greek Politics in the Era of Eleftherios Venizelos. London: Lexington Books. ISBN 9781498587396.

- Karakasidou, Anastasia (2002). "The Burden of the Balkans". Anthropological Quarterly. 75 (3): 575–589. JSTOR 3318205.

- Kutbay, Elif Yeneroğlu (2014). "Economic and Commercial Conditions of the Island of Rhodes at the Beginning of the 20th Century, According to the Reports of Sir Alfred Biliotti" (PDF). Journal of Modern Turkish History Studies. 14 (29): 39–56.

- Lightfoot, Christopher S. (1998). "Survey Work at Satala: A Roman Legionary Fortress in North-East Turkey". In Matthews, Roger (ed.). Ancient Anatolia: Fifty Years' Work by the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara. London: British Institute at Ankara. pp. 273–284. ISBN 1898249113 – via Academia.edu.

- Llewellyn-Smith, Michael (2021). Venizelos: The Making of a Greek Statesman, 1864–1914. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197610824.

- Matthew, Henry Colin Gray (2004). "Stanley, Frederick Arthur, Sixteenth Earl of Derby". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- MacGillivray, Joseph Alexander (2000). Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 9780809030354.

- McGuire, Valerie (2020). Italy's Sea: Empire and Nation in the Mediterranean, 1895–1945. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 9781800348004.

- Meeker, Michael (2010) [2004]. "Greeks Who Are Muslims". In Shankland, David (ed.). Archaeology, Anthropology and Heritage in the Balkans and Anatolia: The Life and Times of F.W. Hasluck, 1878–1920. Vol. 2. Piscataway: Gorgias Press. pp. 299–325. doi:10.31826/9781463225438. ISBN 9781463225438.

- Miller, William (1934) [1910]. "The Ottoman Empire and the Balkan Peninsula". In Ward, Adolphus; Prothero, George W.; Leathes, Stanley (eds.). The Cambridge Modern History. Vol. 12. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 381–428. OCLC 929406450 – via Internet Archive.

- Mitford, Terence Bruce (1974). "Biliotti's Excavations at Satala". Anatolian Studies. 24: 221–244. JSTOR 3642610.

- Mylonakis, Leonidas (2023). Piracy in the Eastern Mediterranean: Maritime Marauders in the Greek and Ottoman Aegean. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9780755643608.

- Plarr, Victor (1899). Men and Women of the Time: A Dictionary of Contemporaries (15th ed.). London: G. Routledge. OCLC 5094803 – via Internet Archive.

- Rathberger, Andreas (2010). "Austria–Hungary, the Cretan Crisis, and the Ambassadors' Conference of Constantinople in 1896". In Suppan, Arnold; Graf, Maximilian (eds.). From the Austrian Empire to Communist East Central Europe. Münster: Lit Verlag. pp. 83–112. ISBN 9783643502353.

- Salmon, Nicholas (2019a). "Archives and Attribution: Reconstructing the British Museum's Excavations of Kamiros". In Schierup, Stine (ed.). Documenting Ancient Rhodes: Archaeological Expeditions and Rhodian Antiquities. Gōsta Enbom Monographs. Vol. 6. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. pp. 98–112. ISBN 9788771249873 – via Academia.edu.

- Salmon, Nicholas (2019b). "Excavation and Documentation of the Rhodian Countryside and Dodecanese Islands in the First Millennium BC". Archaeological Reports. 65: 157–175. JSTOR 26867454.

- Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1984). The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571. Vol. 3: The Sixteenth Century. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. OCLC 1241678661.

- Summerer, Lâtife (2015). "Bulls and Men on the Mountaintop: Votive Terracottas from Çirişli Tepe (Central Black Sea)". In Muller, Arthur; Lalı, Ergün (eds.). Figurines de terre cuite en Méditerranée grecque et romaine [Terracotta Figurines in the Greek and Roman Mediterranean]. Vol. 2. Villeneuve d’Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion. pp. 571–588. ISBN 9782757411339 – via Academia.edu.

- Villing, Alexandra (2019). "The Archaeology of Rhodes and the British Museum: Facing the Challenges of 19th-Century Excavations". In Schierup, Stine (ed.). Documenting Ancient Rhodes: Archaeological Expeditions and Rhodian Antiquities. Gōsta Enbom Monographs. Vol. 6. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. pp. 71–98. ISBN 9788771249873 – via Academia.edu.

Old material

who joined the British Foreign Service and eventually rose to become one of its most distinguished consular officers in the late 19th century. He was one of the first reporters of the ethnic cleansing of Turkish Cretan civilians in 1897 by local Greek troops.[1]

Biliotti's despatches, though written in slightly poor English, are recognized as being of major value for 21st century scholars in fields as different as diplomatic history, anthropology, and of course archaeology.[2]

In 1897, Biliotti reported that 851 Turkish Cretans were killed by Greek Cretans in Lasithi. This number included 201 male and 173 female children.[1]

His service in Crete covered the period of the revolutionary movements of 1889, 1895 and 1897, in all of which Britain was concerned as one of the Great Powers. His service at Salonica saw the beginnings of the guerilla warfare which would eventually lead to the Balkan Wars.

References

- ^ a b McT, Mick. "Sitia 1897".

- ^ Barchard, David. "The Fearless and Self-reliant Servant: The Life and Career of Sir Alfred Biliotti (1833–1915), An Italian Levantine in British Service" (PDF). Studi Miceni ed Egeo-Anatolici. 48: 5–53. Retrieved 12 February 2020.