User:LittleLazyLass/Ankylopollexia

| LittleLazyLass/Ankylopollexia Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstruction of the T. rex type specimen at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Tyrannosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Tyrannosaurinae |

| Clade: | †Tyrannosaurini |

| Genus: | †Tyrannosaurus Osborn, 1905 |

| Type species | |

| †Tyrannosaurus rex Osborn, 1905

| |

| Other species | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Genus synonymy

Species synonymy

| |

Tyrannosaurus (/tɪˌrænəˈsɔːrəs, taɪ-/)[a] is a genus of large theropod dinosaur. The type species Tyrannosaurus rex (rex meaning "king" in Latin), often shortened to T. rex or colloquially T-Rex, is one of the best represented theropods. It lived throughout what is now western North America, on what was then an island continent known as Laramidia. Tyrannosaurus had a much wider range than other tyrannosaurids. Fossils are found in a variety of rock formations dating to the latest Campanian-Maastrichtian ages of the Late Cretaceous period, 72.7 to 66 million years ago. It was the last known member of the tyrannosaurids and among the last non-avian dinosaurs to exist before the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event.

Like other tyrannosaurids, Tyrannosaurus was a bipedal carnivore with a massive skull balanced by a long, heavy tail. Relative to its large and powerful hind limbs, the forelimbs of Tyrannosaurus were short but unusually powerful for their size, and they had two clawed digits. The most complete specimen measures 12.3–12.4 m (40–41 ft) in length, but according to most modern estimates, Tyrannosaurus could have exceeded sizes of 13 m (43 ft) in length, 3.7–4 m (12–13 ft) in hip height, and 8.8 tonnes (8.7 long tons; 9.7 short tons) in mass. Although some other theropods might have rivaled or exceeded Tyrannosaurus in size, it is still among the largest known land predators, with its estimated bite force being the largest among all terrestrial animals. By far the largest carnivore in its environment, Tyrannosaurus rex was most likely an apex predator, preying upon hadrosaurs, juvenile armored herbivores like ceratopsians and ankylosaurs, and possibly sauropods. Some experts have suggested the dinosaur was primarily a scavenger. The question of whether Tyrannosaurus was an apex predator or a pure scavenger was among the longest debates in paleontology. Most paleontologists today accept that Tyrannosaurus was both an active predator and a scavenger.

Specimens of Tyrannosaurus rex include some that are nearly complete skeletons. Soft tissue and proteins have been reported in at least one of these specimens. The abundance of fossil material has allowed significant research into many aspects of its biology, including its life history and biomechanics. The feeding habits, physiology, and potential speed of Tyrannosaurus rex are a few subjects of debate. Its taxonomy is also controversial, as some scientists consider Tarbosaurus bataar from Asia to be a third Tyrannosaurus species, while others maintain Tarbosaurus is a separate genus. Several other genera of North American tyrannosaurids have also been synonymized with Tyrannosaurus. At present, two species of Tyrannosaurus are considered valid; the type species, T. rex, and the earlier and more recently discovered T. mcraeensis.

As the archetypal theropod, Tyrannosaurus has been one of the best-known dinosaurs since the early 20th century and has been featured in film, advertising, postal stamps, and many other media.

History of research

Earliest finds

A tooth from what is now documented as a Tyrannosaurus rex was found in July 1874 upon South Table Mountain (Colorado) by Jarvis Hall (Colorado) student Peter T. Dotson under the auspices of Prof. Arthur Lakes near Golden, Colorado.[1] In the early 1890s, John Bell Hatcher collected postcranial elements in eastern Wyoming. The fossils were believed to be from the large species Ornithomimus grandis (now Deinodon) but are now considered T. rex remains.[2]

In 1892, Edward Drinker Cope found two vertebral fragments of a large dinosaur. Cope believed the fragments belonged to an "agathaumid" (ceratopsid) dinosaur, and named them Manospondylus gigas, meaning "giant porous vertebra", in reference to the numerous openings for blood vessels he found in the bone.[2] The M. gigas remains were, in 1907, identified by Hatcher as those of a theropod rather than a ceratopsid.[3]

Henry Fairfield Osborn recognized the similarity between Manospondylus gigas and T. rex as early as 1917, by which time the second vertebra had been lost. Owing to the fragmentary nature of the Manospondylus vertebrae, Osborn did not synonymize the two genera, instead considering the older genus indeterminate.[4] In June 2000, the Black Hills Institute found around 10% of a Tyrannosaurus skeleton (BHI 6248) at a site that might have been the original M. gigas locality.[5]

Skeleton discovery and naming

Barnum Brown, assistant curator of the American Museum of Natural History, found the first partial skeleton of T. rex in eastern Wyoming in 1900. Brown found another partial skeleton in the Hell Creek Formation in Montana in 1902, comprising approximately 34 fossilized bones.[6] Writing at the time Brown said "Quarry No. 1 contains the femur, pubes, humerus, three vertebrae and two undetermined bones of a large Carnivorous Dinosaur not described by Marsh. ... I have never seen anything like it from the Cretaceous."[7] Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the American Museum of Natural History, named the second skeleton T. rex in 1905. The generic name is derived from the Greek words τύραννος (tyrannos, meaning "tyrant") and σαῦρος (sauros, meaning "lizard"). Osborn used the Latin word rex, meaning "king", for the specific name. The full binomial therefore translates to "tyrant lizard the king" or "King Tyrant Lizard", emphasizing the animal's size and presumed dominance over other species of the time.[6]

Osborn named the other specimen Dynamosaurus imperiosus in a paper in 1905.[6] In 1906, Osborn recognized that the two skeletons were from the same species and selected Tyrannosaurus as the preferred name.[8] The original Dynamosaurus material resides in the collections of the Natural History Museum, London.[9] In 1941, the T. rex type specimen was sold to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, for $7,000.[7] Dynamosaurus would later be honored by the 2018 description of another species of tyrannosaurid by Andrew McDonald and colleagues, Dynamoterror dynastes, whose name was chosen in reference to the 1905 name, as it had been a "childhood favorite" of McDonald's.[10]

From the 1910s through the end of the 1950s, Barnum's discoveries remained the only specimens of Tyrannosaurus, as the Great Depression and wars kept many paleontologists out of the field.[5]

Resurgent interest

Beginning in the 1960s, there was renewed interest in Tyrannosaurus, resulting in the recovery of 42 skeletons (5–80% complete by bone count) from Western North America.[5] In 1967, Dr. William MacMannis located and recovered the skeleton named "MOR 008", which is 15% complete by bone count and has a reconstructed skull displayed at the Museum of the Rockies. The 1990s saw numerous discoveries, with nearly twice as many finds as in all previous years, including two of the most complete skeletons found to date: Sue and Stan.[5]

Sue Hendrickson, an amateur paleontologist, discovered the most complete (approximately 85%) and largest Tyrannosaurus skeleton in the Hell Creek Formation on August 12, 1990. The specimen Sue, named after the discoverer, was the object of a legal battle over its ownership. In 1997, the litigation was settled in favor of Maurice Williams, the original land owner. The fossil collection was purchased by the Field Museum of Natural History at auction for $7.6 million, making it the most expensive dinosaur skeleton until the sale of Stan for $31.8 million in 2020.[11] From 1998 to 1999, Field Museum of Natural History staff spent over 25,000 hours taking the rock off the bones.[12] The bones were then shipped to New Jersey where the mount was constructed, then shipped back to Chicago for the final assembly. The mounted skeleton opened to the public on May 17, 2000, in the Field Museum of Natural History. A study of this specimen's fossilized bones showed that Sue reached full size at age 19 and died at the age of 28, the longest estimated life of any tyrannosaur known.[13]

Another Tyrannosaurus, nicknamed Stan (BHI 3033), in honor of amateur paleontologist Stan Sacrison, was recovered from the Hell Creek Formation in 1992. Stan is the second most complete skeleton found, with 199 bones recovered representing 70% of the total.[14] This tyrannosaur also had many bone pathologies, including broken and healed ribs, a broken (and healed) neck, and a substantial hole in the back of its head, about the size of a Tyrannosaurus tooth.[15]

In 1998, Bucky Derflinger noticed a T. rex toe exposed above ground, making Derflinger, who was 20 years old at the time, the youngest person to discover a Tyrannosaurus. The specimen, dubbed Bucky in honor of its discoverer, was a young adult, 3.0 metres (10 ft) tall and 11 metres (35 ft) long. Bucky is the first Tyrannosaurus to be found that preserved a furcula (wishbone). Bucky is permanently displayed at The Children's Museum of Indianapolis.[16]

In the summer of 2000, crews organized by Jack Horner discovered five Tyrannosaurus skeletons near the Fort Peck Reservoir.[17] In 2001, a 50% complete skeleton of a juvenile Tyrannosaurus was discovered in the Hell Creek Formation by a crew from the Burpee Museum of Natural History. Dubbed Jane (BMRP 2002.4.1), the find was thought to be the first known skeleton of a pygmy tyrannosaurid, Nanotyrannus, but subsequent research revealed that it is more likely a juvenile Tyrannosaurus, and the most complete juvenile example known;[18] Jane is exhibited at the Burpee Museum of Natural History.[19] In 2002, a skeleton named Wyrex, discovered by amateur collectors Dan Wells and Don Wyrick, had 114 bones and was 38% complete. The dig was concluded over 3 weeks in 2004 by the Black Hills Institute with the first live online Tyrannosaurus excavation providing daily reports, photos, and video.[5]

In 2006, Montana State University revealed that it possessed the largest Tyrannosaurus skull yet discovered (from a specimen named MOR 008), measuring 5 feet (152 cm) long.[20] Subsequent comparisons indicated that the longest head was 136.5 centimetres (53.7 in) (from specimen LACM 23844) and the widest head was 90.2 centimetres (35.5 in) (from Sue).[21]

Footprints

Two isolated fossilized footprints have been tentatively assigned to T. rex. The first was discovered at Philmont Scout Ranch, New Mexico, in 1983 by American geologist Charles Pillmore. Originally thought to belong to a hadrosaurid, examination of the footprint revealed a large 'heel' unknown in ornithopod dinosaur tracks, and traces of what may have been a hallux, the dewclaw-like fourth digit of the tyrannosaur foot. The footprint was published as the ichnogenus Tyrannosauripus pillmorei in 1994, by Martin Lockley and Adrian Hunt. Lockley and Hunt suggested that it was very likely the track was made by a T. rex, which would make it the first known footprint from this species. The track was made in what was once a vegetated wetland mudflat. It measures 83 centimeters (33 in) long by 71 centimeters (28 in) wide.[22]

A second footprint that may have been made by a Tyrannosaurus was first reported in 2007 by British paleontologist Phil Manning, from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana. This second track measures 72 centimeters (28 in) long, shorter than the track described by Lockley and Hunt. Whether or not the track was made by Tyrannosaurus is unclear, though Tyrannosaurus is the only large theropod known to have existed in the Hell Creek Formation.[23][24]

A set of footprints in Glenrock, Wyoming dating to the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous and hailing from the Lance Formation were described by Scott Persons, Phil Currie and colleagues in 2016, and are believed to belong to either a juvenile T. rex or the dubious tyrannosaurid Nanotyrannus lancensis. From measurements and based on the positions of the footprints, the animal was believed to be traveling at a walking speed of around 2.8 to 5 miles per hour and was estimated to have a hip height of 1.56 to 2.06 m (5.1 to 6.8 ft).[25][26][27] A follow-up paper appeared in 2017, increasing the speed estimations by 50–80%.[28]

Description

Size

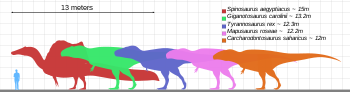

T. rex was one of the largest land carnivores of all time. One of the largest and the most complete specimens, nicknamed Sue (FMNH PR2081), is located at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. Sue measured 12.3–12.4 m (40.4–40.7 ft) long,[29][30] was 3.66–3.96 meters (12–13 ft) tall at the hips,[31][32][33] and according to the most recent studies, using a variety of techniques, maximum body masses have been estimated approximately 8.4–8.46 metric tons (9.26–9.33 short tons).[34][35] A specimen nicknamed Scotty (RSM P2523.8), located at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum, is reported to measure 13 m (43 ft) in length. Using a mass estimation technique that extrapolates from the circumference of the femur, Scotty was estimated as the largest known specimen at 8.87 metric tons (9.78 short tons) in body mass.[34][36]

Not every adult Tyrannosaurus specimen recovered is as big. Historically average adult mass estimates have varied widely over the years, from as low as 4.5 metric tons (5.0 short tons),[37][38] to more than 7.2 metric tons (7.9 short tons),[39] with most modern estimates ranging between 5.4 and 8.0 metric tons (6.0 and 8.8 short tons).[29][40][41][42][43]

Skull

The largest known T. rex skulls measure up to 1.54 meters (5 ft) in length.[20][31] Large fenestrae (openings) in the skull reduced weight, as in all carnivorous theropods. In other respects Tyrannosaurus's skull was significantly different from those of large non-tyrannosaurid theropods. It was extremely wide at the rear but had a narrow snout, allowing unusually good binocular vision.[44][45] The skull bones were massive and the nasals and some other bones were fused, preventing movement between them; but many were pneumatized (contained a "honeycomb" of tiny air spaces) and thus lighter. These and other skull-strengthening features are part of the tyrannosaurid trend towards an increasingly powerful bite, which easily surpassed that of all non-tyrannosaurids.[46][47][48] The tip of the upper jaw was U-shaped (most non-tyrannosauroid carnivores had V-shaped upper jaws), which increased the amount of tissue and bone a tyrannosaur could rip out with one bite, although it also increased the stresses on the front teeth.[49]

The teeth of T. rex displayed marked heterodonty (differences in shape).[50][51] The premaxillary teeth, four per side at the front of the upper jaw, were closely packed, D-shaped in cross-section, had reinforcing ridges on the rear surface, were incisiform (their tips were chisel-like blades) and curved backwards. The D-shaped cross-section, reinforcing ridges and backwards curve reduced the risk that the teeth would snap when Tyrannosaurus bit and pulled. The remaining teeth were robust, like "lethal bananas" rather than daggers, more widely spaced and also had reinforcing ridges.[52] Those in the upper jaw, twelve per side in mature individuals,[50] were larger than their counterparts of the lower jaw, except at the rear. The largest found so far is estimated to have been 30.5 centimeters (12 in) long including the root when the animal was alive, making it the largest tooth of any carnivorous dinosaur yet found.[53] The lower jaw was robust. Its front dentary bone bore thirteen teeth. Behind the tooth row, the lower jaw became notably taller.[50] The upper and lower jaws of Tyrannosaurus, like those of many dinosaurs, possessed numerous foramina, or small holes in the bone. Various functions have been proposed for these foramina, such as a crocodile-like sensory system[54] or evidence of extra-oral structures such as scales or potentially lips,[55][56][57] with subsequent research on theropod tooth wear patterns supporting such a proposition.[58]

Skeleton

The vertebral column of Tyrannosaurus consisted of ten neck vertebrae, thirteen back vertebrae and five sacral vertebrae. The number of tail vertebrae is unknown and could well have varied between individuals but probably numbered at least forty. Sue was mounted with forty-seven of such caudal vertebrae.[50] The neck of T. rex formed a natural S-shaped curve like that of other theropods. Compared to these, it was exceptionally short, deep and muscular to support the massive head. The second vertebra, the axis, was especially short. The remaining neck vertebrae were weakly opisthocoelous, i.e. with a convex front of the vertebral body and a concave rear. The vertebral bodies had single pleurocoels, pneumatic depressions created by air sacs, on their sides.[50] The vertebral bodies of the torso were robust but with a narrow waist. Their undersides were keeled. The front sides were concave with a deep vertical trough. They had large pleurocoels. Their neural spines had very rough front and rear sides for the attachment of strong tendons. The sacral vertebrae were fused to each other, both in their vertebral bodies and neural spines. They were pneumatized. They were connected to the pelvis by transverse processes and sacral ribs. The tail was heavy and moderately long, in order to balance the massive head and torso and to provide space for massive locomotor muscles that attached to the thighbones. The thirteenth tail vertebra formed the transition point between the deep tail base and the middle tail that was stiffened by a rather long front articulation processes. The underside of the trunk was covered by eighteen or nineteen pairs of segmented belly ribs.[50]

The shoulder girdle was longer than the entire forelimb. The shoulder blade had a narrow shaft but was exceptionally expanded at its upper end. It connected via a long forward protrusion to the coracoid, which was rounded. Both shoulder blades were connected by a small furcula. The paired breast bones possibly were made of cartilage only.[50]

The forelimb or arm was very short. The upper arm bone, the humerus, was short but robust. It had a narrow upper end with an exceptionally rounded head. The lower arm bones, the ulna and radius, were straight elements, much shorter than the humerus. The second metacarpal was longer and wider than the first, whereas normally in theropods the opposite is true. The forelimbs had only two clawed fingers,[50] along with an additional splint-like small third metacarpal representing the remnant of a third digit.[59]

The pelvis was a large structure. Its upper bone, the ilium, was both very long and high, providing an extensive attachment area for hindlimb muscles. The front pubic bone ended in an enormous pubic boot, longer than the entire shaft of the element. The rear ischium was slender and straight, pointing obliquely to behind and below.[50]

In contrast to the arms, the hindlimbs were among the longest in proportion to body size of any theropod. In the foot, the metatarsus was "arctometatarsalian", meaning that the part of the third metatarsal near the ankle was pinched. The third metatarsal was also exceptionally sinuous.[50] Compensating for the immense bulk of the animal, many bones throughout the skeleton were hollowed, reducing its weight without significant loss of strength.[50]

Classification

Tyrannosaurus is the type genus of the superfamily Tyrannosauroidea, the family Tyrannosauridae, and the subfamily Tyrannosaurinae; in other words it is the standard by which paleontologists decide whether to include other species in the same group. Other members of the tyrannosaurine subfamily include the North American Daspletosaurus and the Asian Tarbosaurus,[18][60] both of which have occasionally been synonymized with Tyrannosaurus.[61]

Tyrannosaurids were once commonly thought to be descendants of earlier large theropods such as megalosaurs and carnosaurs, although more recently they were reclassified with the generally smaller coelurosaurs.[49] The earliest tyrannosaur group were the crested proceratosaurids, while later and more derived members belong to the Pantyrannosauria. Tyrannosaurs started out as small theropods; however at least some became larger by the Early Cretaceous.

Tyrannosauroids are characterized by their fused nasals and dental arrangement. Pantyrannosaurs are characterized by unique features in their hips as well as an enlarged foramen in the quadrate, a broad postorbital and hourglass shaped nasals. Some of the more derived pantyrannosaurs lack nasal pneumaticity and have a lower humerus to femur ratio with their arms starting to see some reduction. Some pantyrannosaurs started developing an arctometatarsus. Eutyrannosaurs have a rough texture on their nasal bones and their mandibular fenestra is reduced externally. Tyrannosaurids lack kinetic skulls or special crests on their nasal bones, and have a lacrimal with a distinctive process on it. Tyrannosaurids also have an interfenestral strut that is less than half as big as the maxillary fenestra.[62]

It is quite likely that tyrannosauroids rose to prominence after the decline in allosauroid and megalosauroid diversity seen during the early stages of the Late Cretaceous. Below is a simple cladogram of general tyrannosauroid relationships that was found after an analysis conducted by Li and colleagues in 2009.[63]

Many phylogenetic analyses have found Tarbosaurus bataar to be the sister taxon of T. rex.[60] The discovery of the tyrannosaurid Lythronax further indicates that Tarbosaurus and Tyrannosaurus are closely related, forming a clade with fellow Asian tyrannosaurid Zhuchengtyrannus, with Lythronax being their sister taxon.[64][65] A further study from 2016 by Steve Brusatte, Thomas Carr and colleagues, also indicates that Tyrannosaurus may have been an immigrant from Asia, as well as a possible descendant of Tarbosaurus.[66]

Below is the cladogram of Tyrannosauridae based on the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Loewen and colleagues in 2013.[64]

| Tyrannosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

In their 2024 description of Tyrannosaurus mcraeensis, Dalman et al. recovered similar results to previous analyses, with Tyrannosaurus as the sister taxon to the clade formed by Tarbosaurus and Zhuchengtyrannus, called the Tyrannosaurini. They also found support for a monophyletic clade containing Daspletosaurus and Thanatotheristes, typically referred to as the Daspletosaurini.[67][68]

Paleoecology

Tyrannosaurus lived during what is referred to as the Lancian faunal stage (Maastrichtian age) at the end of the Late Cretaceous. Tyrannosaurus ranged from Canada in the north to at least New Mexico in the south of Laramidia.[5] During this time Triceratops was the major herbivore in the northern portion of its range, while the titanosaurian sauropod Alamosaurus "dominated" its southern range. Tyrannosaurus remains have been discovered in different ecosystems, including inland and coastal subtropical, and semi-arid plains.

Several notable Tyrannosaurus remains have been found in the Hell Creek Formation. During the Maastrichtian this area was subtropical, with a warm and humid climate. The flora consisted mostly of angiosperms, but also included trees like dawn redwood (Metasequoia) and Araucaria. Tyrannosaurus shared this ecosystem with ceratopsians Leptoceratops, Torosaurus, and Triceratops, the hadrosaurid Edmontosaurus annectens, the parksosaurid Thescelosaurus, the ankylosaurs Ankylosaurus and Denversaurus, the pachycephalosaurs Pachycephalosaurus and Sphaerotholus, and the theropods Ornithomimus, Struthiomimus, Acheroraptor, Dakotaraptor, Pectinodon and Anzu.[69]

Another formation with Tyrannosaurus remains is the Lance Formation of Wyoming. This has been interpreted as a bayou environment similar to today's Gulf Coast. The fauna was very similar to Hell Creek, but with Struthiomimus replacing its relative Ornithomimus. The small ceratopsian Leptoceratops also lived in the area.[70]

In its southern range, specifically based on remains discovered from the North Horn Formation of Utah, Tyrannosaurus rex lived alongside the titanosaur Alamosaurus, the ceratopsid Torosaurus and the indeterminate troodontids and hadrosaurids.[71][72] Tyrannosaurus mcraeensis from the McRae Group of New Mexico coexisted with the ceratopsid Sierraceratops and possibly the titanosaur Alamosaurus.[67] Potential remains identified as cf. Tyrannosaurus have also been discovered from the Javelina Formation of Texas,[67] where the remains of the titanosaur Alamosaurus, the ceratopsid Bravoceratops, the pterosaurs Quetzalcoatlus and Wellnhopterus, and possible species of troodontids and hadrosaurids are found.[73][74][75] Its southern range is thought to have been dominated by semi-arid inland plains, following the probable retreat of the Western Interior Seaway as global sea levels fell.[76]

Tyrannosaurus may have also inhabited Mexico's Lomas Coloradas Formation in Sonora. Though skeletal evidence is lacking, six shed and broken teeth from the fossil bed have been thoroughly compared with other theropod genera and appear to be identical to those of Tyrannosaurus. If true, the evidence indicates the range of Tyrannosaurus was possibly more extensive than previously believed.[77] It is possible that tyrannosaurs were originally Asian species, migrating to North America before the end of the Cretaceous period.[78]

Population estimates

According to studies published in 2021 by Charles Marshall et al., the total population of adult Tyrannosaurus at any given time was perhaps 20,000 individuals, with computer estimations also suggesting a total population no lower than 1,300 and no higher than 328,000. The authors themselves suggest that the estimate of 20,000 individuals is probably lower than what should be expected, especially when factoring in that disease pandemics could easily wipe out such a small population. Over the span of the genus' existence, it is estimated that there were about 127,000 generations and that this added up to a total of roughly 2.5 billion animals until their extinction.[79][80]

In the same paper, it is suggested that in a population of Tyrannosaurus adults numbering 20,000, the number of individuals living in an area the size of California could be as high as 3,800 animals, while an area the size of Washington D.C. could support a population of only two adult Tyrannosaurus. The study does not take into account the number of juvenile animals in the genus present in this population estimate due to their occupation of a different niche than the adults, and thus it is likely the total population was much higher when accounting for this factor. Simultaneously, studies of living carnivores suggest that some predator populations are higher in density than others of similar weight (such as jaguars and hyenas, which are similar in weight but have vastly differing population densities). Lastly, the study suggests that in most cases, only one in 80 million Tyrannosaurus would become fossilized, while the chances were likely as high as one in every 16,000 of an individual becoming fossilized in areas that had more dense populations.[79][80]

Meiri (2022) questioned the reliability of the estimates, citing uncertainty in metabolic rate, body size, sex and age-specific survival rates, habitat requirements and range size variability as shortcomings Marshall et al. did not take into account.[81] The authors of the original publication replied that while they agree that their reported uncertainties were probably too small, their framework is flexible enough to accommodate uncerainty in physiology, and that their calculations do not depend on short-term changes in population density and geographic range, but rather on their long-term averages. Finally, they remark that they did estimate the range of reasonable survivorship curves and that they did include uncertainty in the time of onset of sexual maturity and in the growth curve by incorporating the uncertainty in the maximum body mass.[82]

Cultural significance

Since it was first described in 1905, T. rex has become the most widely recognized dinosaur species in popular culture. It is the only dinosaur that is commonly known to the general public by its full scientific name (binomial name) and the scientific abbreviation T. rex has also come into wide usage.[50] Robert T. Bakker notes this in The Dinosaur Heresies and explains that, "a name like 'T. rex' is just irresistible to the tongue."[38]

See also

- History of paleontology

- Sue (dinosaur) (FMNH-PR-2081)

- Tyrannosauridae

Notes

- ^ lit. 'tyrant lizard'; from Ancient Greek τύραννος (túrannos) 'tyrant', and σαῦρος (saûros) 'lizard'

References

- ^ "The Colorado Transcript". July 8, 1874 – via www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org.

- ^ a b Breithaupt, B. H.; Southwell, E. H.; Matthews, N. A. (October 15, 2005). "In Celebration of 100 years of Tyrannosaurus rex: Manospondylus gigas, Ornithomimus grandis, and Dynamosaurus imperiosus, the Earliest Discoveries of Tyrannosaurus rex in the West". Abstracts with Programs; 2005 Salt Lake City Annual Meeting. 37 (7). Geological Society of America: 406. ISSN 0016-7592. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ^ Hatcher, J. B. (1907). "The Ceratopsia". Monographs of the United States Geological Survey. 49: 113–114. ISSN 0886-7550.

- ^ Osborn, H. F. (1917). "Skeletal adaptations of Ornitholestes, Struthiomimus, Tyrannosaurus". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 35 (43): 733–771. hdl:2246/1334.

- ^ a b c d e f Cite error: The named reference

larson2008was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

osborn1905was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Dingus, L.; Norell, M. (May 3, 2010). Barnum Brown: The Man Who Discovered Tyrannosaurus rex. University of California Press. pp. 90, 124. ISBN 978-0-520-94552-4.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

osborn1906was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Breithaupt, B. H.; Southwell, E. H.; Matthews, N. A. (2006). Lucas, S. G.; Sullivan, R. M. (eds.). "Dynamosaurus imperiosus and the earliest discoveries of Tyrannosaurus rex in Wyoming and the West" (PDF). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 35: 258.

The original skeleton of Dynamosaurus imperiosus (AMNH 5866/BM R7995), together with other T. rex material (including parts of AMNH 973, 5027, and 5881), were sold to the British Museum of Natural History (now The Natural History Museum) in 1960. This material was used in an interesting 'half-mount' display of this dinosaur in London. Currently the material resides in the research collections.

- ^ McDonald, A. T.; Wolfe, D. G.; Dooley, A. C. Jr. (2018). "A new tyrannosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico". PeerJ. 6: 6:e5749. doi:10.7717/peerj.5749. PMC 6183510. PMID 30324024.

- ^ Small, Zachary (October 7, 2020). "T. Rex Skeleton Brings $31.8 Million at Christie's Auction". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 7, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ "Preparing Sue's bones". Sue at the Field Museum. The Field Museum. 2007. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ Erickson, G.; Makovicky, P. J.; Currie, P. J.; Norell, M.; Yerby, S.; Brochu, C. A. (May 26, 2004). "Gigantism and life history parameters of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs" (PDF). Nature. 430 (7001): 772–775. Bibcode:2004Natur.430..772E. doi:10.1038/nature02699. PMID 15306807. S2CID 4404887. (Erratum: doi:10.1038/nature16487, PMID 26675726, Retraction Watch)

- ^ "Stan". The University of Manchester. September 18, 2010. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010.

- ^ Fiffer, S. (2000). "Jurassic Farce". Tyrannosaurus Sue. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-0-7167-4017-9.

- ^ "Meet Bucky The Teenage T. Rex". Children's Museum of Indianapolis. July 7, 2014. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ "Dig pulls up five T. rex specimens". BBC News. October 10, 2000. Retrieved December 13, 2008.

- ^ a b Currie, P. J.; Hurum, J. H.; Sabath, K. (2003). "Skull structure and evolution in tyrannosaurid dinosaurs" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 48 (2): 227–234. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ^ Black, Riley (October 28, 2015). "Tiny terror: Controversial dinosaur species is just an awkward tween Tyrannosaurus". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ a b "Museum unveils world's largest T-rex skull". 2006. Archived from the original on April 14, 2006. Retrieved April 7, 2006.

- ^ Gignac, P. M.; Erickson, G. M. (2017). "The biomechanics behind extreme osteophagy in Tyrannosaurus rex". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 2012. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.2012G. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-02161-w. PMC 5435714. PMID 28515439.

- ^ Lockley, M. G.; Hunt, A. P. (1994). "A track of the giant theropod dinosaur Tyrannosaurus from close to the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary, northern New Mexico". Ichnos. 3 (3): 213–218. Bibcode:1994Ichno...3..213L. doi:10.1080/10420949409386390.

- ^ "A Probable Tyrannosaurid Track From the Hell Creek Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Montana, United States". National Museum of History News. 2007. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ^ Manning, P. L.; Ott, C.; Falkingham, P. L. (2009). "The first tyrannosaurid track from the Hell Creek Formation (Late Cretaceous), Montana, U.S.A". PALAIOS. 23 (10): 645–647. Bibcode:2008Palai..23..645M. doi:10.2110/palo.2008.p08-030r. S2CID 129985735.

- ^ Smith, S. D.; Persons, W. S.; Xing, L. (2016). "A "Tyrannosaur" trackway at Glenrock, Lance Formation (Maastrichtian), Wyoming". Cretaceous Research. 61 (1): 1–4. Bibcode:2016CrRes..61....1S. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.12.020.

- ^ Perkins, S. (2016). "You could probably have outrun a T. rex". Palaeontology. doi:10.1126/science.aae0270.

- ^ Walton, T. (2016). "Forget all you know from Jurassic Park: For speed, T. rex beats velociraptors". USA Today. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ Ruiz, J. (2017). "Comments on "A tyrannosaur trackway at Glenrock, Lance Formation (Maastrichtian), Wyoming" (Smith et al., Cretaceous Research, v. 61, pp. 1–4, 2016)". Cretaceous Research. 82: 81–82. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2017.05.033.

- ^ a b Hutchinson, J. R.; Bates, K. T.; Molnar, J.; Allen, V.; Makovicky, P. J. (2011). "A Computational Analysis of Limb and Body Dimensions in Tyrannosaurus rex with Implications for Locomotion, Ontogeny, and Growth". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e26037. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...626037H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026037. PMC 3192160. PMID 22022500.

- ^ Holtz, T. R. (2011). "Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix" (PDF). Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ a b "Sue Fact Sheet" (PDF). Sue at the Field Museum. Field Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 18, 2016.

- ^ "How well do you know SUE?". Field Museum of Natural History. August 11, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ "Sue the T. Rex". Field Museum. February 5, 2018. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ a b Persons, S. W.; Currie, P. J.; Erickson, G. M. (2019). "An Older and Exceptionally Large Adult Specimen of Tyrannosaurus rex". The Anatomical Record. 303 (4): 656–672. doi:10.1002/ar.24118. ISSN 1932-8486. PMID 30897281.

- ^ Hartman, Scott (July 7, 2013). "Mass estimates: North vs South redux". Scott Hartman's Skeletal Drawing.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- ^ Lyle, A. (March 22, 2019). "Paleontologists identify biggest Tyrannosaurus rex ever discovered". Folio, University of Alberta. Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ Anderson, J. F.; Hall-Martin, A. J.; Russell, D. (1985). "Long bone circumference and weight in mammals, birds and dinosaurs". Journal of Zoology. 207 (1): 53–61. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1985.tb04915.x.

- ^ a b Bakker, R. T. (1986). The Dinosaur Heresies. New York: Kensington Publishing. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-688-04287-5. OCLC 13699558.

- ^ Henderson, D. M. (January 1, 1999). "Estimating the masses and centers of mass of extinct animals by 3-D mathematical slicing". Paleobiology. 25 (1): 88–106.

- ^ Erickson, G. M.; Makovicky, P. J.; Currie, P. J.; Norell, M. A.; Yerby, S. A.; Brochu, C. A. (2004). "Gigantism and comparative life-history parameters of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs" (PDF). Nature. 430 (7001): 772–775. Bibcode:2004Natur.430..772E. doi:10.1038/nature02699. PMID 15306807. S2CID 4404887.

- ^ Farlow, J. O.; Smith, M. B.; Robinson, J. M. (1995). "Body mass, bone 'strength indicator', and cursorial potential of Tyrannosaurus rex". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 15 (4): 713–725. Bibcode:1995JVPal..15..713F. doi:10.1080/02724634.1995.10011257. Archived from the original on October 23, 2008.

- ^ Seebacher, F. (2001). "A new method to calculate allometric length–mass relationships of dinosaurs" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (1): 51–60. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.462.255. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0051:ANMTCA]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 53446536.

- ^ Christiansen, P.; Fariña, R. A. (2004). "Mass prediction in theropod dinosaurs". Historical Biology. 16 (2–4): 85–92. Bibcode:2004HBio...16...85C. doi:10.1080/08912960412331284313. S2CID 84322349.

- ^ Stevens, Kent A. (June 2006). "Binocular vision in theropod dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (2): 321–330. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[321:BVITD]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85694979.

- ^ Jaffe, E. (July 1, 2006). "Sight for 'Saur Eyes: T. rex vision was among nature's best". Science News. 170 (1): 3–4. doi:10.2307/4017288. JSTOR 4017288. Archived from the original on September 29, 2012. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ^ Snively, E.; Henderson, D. M.; Phillips, D. S. (2006). "Fused and vaulted nasals of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs: Implications for cranial strength and feeding mechanics" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 51 (3): 435–454. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ^ Meers, M. B. (August 2003). "Maximum bite force and prey size of Tyrannosaurus rex and their relationships to the inference of feeding behavior". Historical Biology. 16 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1080/0891296021000050755. S2CID 86782853.

- ^ Erickson, G. M.; Van Kirk, S. D.; Su, J.; Levenston, M. E.; Caler, W. E.; Carter, D. R. (1996). "Bite-force estimation for Tyrannosaurus rex from tooth-marked bones". Nature. 382 (6593): 706–708. Bibcode:1996Natur.382..706E. doi:10.1038/382706a0. S2CID 4325859.

- ^ a b Holtz, T. R. (1994). "The Phylogenetic Position of the Tyrannosauridae: Implications for Theropod Systematics". Journal of Paleontology. 68 (5): 1100–1117. Bibcode:1994JPal...68.1100H. doi:10.1017/S0022336000026706. JSTOR 1306180. S2CID 129684676.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Brochu, C. R. (2003). "Osteology of Tyrannosaurus rex: insights from a nearly complete skeleton and high-resolution computed tomographic analysis of the skull". Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoirs. 7: 1–138. doi:10.2307/3889334. JSTOR 3889334.

- ^ Smith, J. B. (December 1, 2005). "Heterodonty in Tyrannosaurus rex: implications for the taxonomic and systematic utility of theropod dentitions". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (4): 865–887. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0865:HITRIF]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86184190.

- ^ Douglas, K.; Young, S. (1998). "The dinosaur detectives". New Scientist. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

One palaeontologist memorably described the huge, curved teeth of T. rex as 'lethal bananas'

- ^ "Sue's vital statistics". Sue at the Field Museum. Field Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved September 15, 2007.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

carr2017was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Morhardt, Ashley (2009). Dinosaur smiles: Do the texture and morphology of the premaxilla, maxilla, and dentary bones of sauropsids provide osteological correlates for inferring extra-oral structures reliably in dinosaurs? (MSc thesis). Western Illinois University.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ MORPHOLOGY, TAXONOMY, AND PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS OF THE MONTEVIALE CROCODYLIANS (OLIGOCENE, ITALY). 2018. p. 67. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- ^ Cullen, Thomas M.; Larson, Derek W.; Witton, Mark P.; Scott, Diane; Maho, Tea; Brink, Kirstin S.; Evans, David C.; Reisz, Robert (March 31, 2023). "Theropod dinosaur facial reconstruction and the importance of soft tissues in paleobiology". Science. 379 (6639): 1348–1352. Bibcode:2023Sci...379.1348C. doi:10.1126/science.abo7877. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 36996202. S2CID 257836765.

- ^ Lipkin, C.; Carpenter, K. (2008). "Looking again at the forelimb of Tyrannosaurus rex". In Carpenter, K.; Larson, P. E. (eds.). Tyrannosaurus rex, the Tyrant King. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 167–190. ISBN 978-0-253-35087-9.

- ^ a b Holtz, T. R. Jr. (2004). "Tyrannosauroidea". In Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.). The dinosauria. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 111–136. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (1988). Predatory dinosaurs of the world: a complete illustrated guide. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-671-61946-6. OCLC 18350868.

- ^ Brusatte, Stephen L.; Norell, Mark A.; Carr, Thomas D.; Erickson, Gregory M.; Hutchinson, John R.; Balanoff, Amy M.; Bever, Gabe S.; Choiniere, Jonah N.; Makovicky, Peter J.; Xu, Xing (September 17, 2010). "Tyrannosaur Paleobiology: New Research on Ancient Exemplar Organisms". Science. 329 (5998): 1481–1485. Bibcode:2010Sci...329.1481B. doi:10.1126/science.1193304. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 20847260.

- ^ Li, Daqing; Norell, Mark A.; Gao, Ke-Qin; Smith, Nathan D.; Makovicky, Peter J. (2009). "A longirostrine tyrannosauroid from the Early Cretaceous of China". Proc Biol Sci. 277 (1679): 183–190. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0249. PMC 2842666. PMID 19386654.

- ^ a b Loewen, M. A.; Irmis, R. B.; Sertich, J. J. W.; Currie, P. J.; Sampson, S. D. (2013). Evans, D. C (ed.). "Tyrant Dinosaur Evolution Tracks the Rise and Fall of Late Cretaceous Oceans". PLoS ONE. 8 (11): e79420. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...879420L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079420. PMC 3819173. PMID 24223179.

- ^ Vergano, D. (November 7, 2013). "Newfound "King of Gore" Dinosaur Ruled Before T. Rex". National Geographic. Archived from the original on November 8, 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ Geggel, L. (February 29, 2016). "T. Rex Was Likely an Invasive Species". Live Science. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

T.mcraeensiswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Scherer, Charlie Roger; Voiculescu-Holvad, Christian (2024). "Re-analysis of a dataset refutes claims of anagenesis within Tyrannosaurus-line tyrannosaurines (Theropoda, Tyrannosauridae)". Cretaceous Research. 155. 105780. Bibcode:2024CrRes.15505780S. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105780. ISSN 0195-6671.

- ^ Estes, R.; Berberian, P. (1970). "Paleoecology of a late Cretaceous vertebrate community from Montana". Breviora. 343: 1–35.

- ^ Derstler, K. (1994). "Dinosaurs of the Lance Formation in eastern Wyoming". In Nelson, G. E. (ed.). The Dinosaurs of Wyoming. Wyoming Geological Association Guidebook, 44th Annual Field Conference. Wyoming Geological Association. pp. 127–146.

- ^ Sampson, Scott D.; Loewon, Mark A. (June 27, 2005). "Tyrannosaurus rex from the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) North Horn Formation of Utah: Biogeographic and Paleoecologic Implications". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (2): 469–472. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0469:TRFTUC]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4524461. S2CID 131583311.

- ^ Cifelli, Richard L.; Nydam, Randall L.; Eaton, Jeffrey G.; Gardner, James D.; Kirkland, James I. (1999). "Vertebrate faunas of the North Horn Formation (Upper Cretaceous–Lower Paleocene), Emery and Sanpete Counties, Utah". In Gillette, David D. (ed.). Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah. Salt Lake City: Utah Geological Survey. pp. 377–388. ISBN 1-55791-634-9.

- ^ Wick, Steven L.; Lehman, Thomas M. (July 1, 2013). "A new ceratopsian dinosaur from the Javelina Formation (Maastrichtian) of West Texas and implications for chasmosaurine phylogeny". Naturwissenschaften. 100 (7): 667–682. Bibcode:2013NW....100..667W. doi:10.1007/s00114-013-1063-0. PMID 23728202. S2CID 16048008. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ Andres, B.; Langston, W. Jr. (2021). "Morphology and taxonomy of Quetzalcoatlus Lawson 1975 (Pterodactyloidea: Azhdarchoidea)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (sup1): 142. Bibcode:2021JVPal..41S..46A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.1907587. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 245125409.

- ^ Tweet, J.S.; Santucci, V.L. (2018). "An Inventory of Non-Avian Dinosaurs from National Park Service Areas" (PDF). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 79: 703–730.

- ^ Jasinski, S. E.; Sullivan, R. M.; Lucas, S. G. (2011). "Taxonomic composition of the Alamo Wash local fauna from the Upper Cretaceous Ojo Alamo Formation (Naashoibito Member) San Juan Basin, New Mexico". Bulletin. 53: 216–271.

- ^ Serrano-Brañas, C. I.; Torres-Rodrígueza, E.; Luna, P. C. R.; González, I.; González-León, C. (2014). "Tyrannosaurid teeth from the Lomas Coloradas Formation, Cabullona Group (Upper Cretaceous) Sonora, México". Cretaceous Research. 49: 163–171. Bibcode:2014CrRes..49..163S. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2014.02.018.

- ^ Brusatte, S. L.; Carr, T. D. (2016). "The phylogeny and evolutionary history of tyrannosauroid dinosaurs". Scientific Reports. 6: 20252. Bibcode:2016NatSR...620252B. doi:10.1038/srep20252. PMC 4735739. PMID 26830019.

- ^ a b Chang, Kenneth (April 15, 2021). "How Many Tyrannosaurus Rexes Ever Lived on Earth? Here's a New Clue". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Marshall, Charles R.; Latorre, Daniel V.; Wilson, Connor J.; Frank, Tanner M.; Magoulick, Katherine M.; Zimmt, Joshua B.; Poust, Ashley W. (April 16, 2021). "Absolute abundance and preservation rate of Tyrannosaurus rex". Science. 372 (6539): 284–287. Bibcode:2021Sci...372..284M. doi:10.1126/science.abc8300. PMID 33859033.

- ^ Meiri, Shai (2022). "Population sizes of T. rex cannot be precisely estimated". Frontiers of Biogeography. 14 (2). doi:10.21425/F5FBG53781. S2CID 245288933.

- ^ Marshall, Charles R.; Latorre, Daniel V.; Wilson, Connor J.; Frank, Tanner M.; Magoulick, Katherine M.; Zimmt, Joshua P.; Poust, Ashley W. (2022). "With what precision can the population size of Tyrannosaurus rex be estimated? A reply to Meiri". Frontiers of Biogeography. 14 (2). doi:10.21425/F5FBG55042. hdl:10852/101238. S2CID 245314491.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Further reading

- Farlow, J. O.; Gatesy, S. M.; Holtz, T. R. Jr.; Hutchinson, J. R.; Robinson, J. M. (2000). "Theropod Locomotion". American Zoologist. 40 (4): 640–663. doi:10.1093/icb/40.4.640. JSTOR 3884284.

External links

- The University of Edinburgh Lecture Dr Stephen Brusatte – Tyrannosaur Discoveries Feb 20, 2015

- 28 species in the tyrannosaur family tree, when and where they lived Stephen Brusatte Thomas Carr 2016

- Australia's answer to T-Rex, State Library of Queensland