Typhoon Tip

Tip at its record peak intensity on October 12 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | October 4, 1979 |

| Extratropical | October 19, 1979 |

| Dissipated | October 24, 1979 |

| Violent typhoon | |

| 10-minute sustained (JMA) | |

| Highest winds | 260 km/h (160 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 870 hPa (mbar); 25.69 inHg (Worldwide record low) |

| Category 5-equivalent super typhoon | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 305 km/h (190 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 870 hPa (mbar); 25.69 inHg (Worldwide record low) |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 99 |

| Damage | $484 million (1979 USD) |

| Areas affected | Caroline Islands, Philippines, Korean Peninsula, Japan, Northeast China, Russian Far East, Alaska |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1979 Pacific typhoon season | |

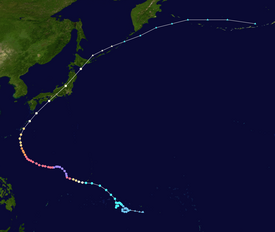

Typhoon Tip, known in the Philippines as Super Typhoon Warling, was an exceptionally large, extremely powerful, and long-lived tropical cyclone that traversed the Western Pacific for 20 days, shattering multiple records worldwide. The forty-third tropical depression, nineteenth tropical storm, twelfth typhoon, and third super typhoon of the 1979 Pacific typhoon season, Tip developed out of a disturbance within the monsoon trough on October 4 near Pohnpei in Micronesia. Initially, Tropical Storm Roger to the northwest hindered the development and motion of Tip, though after the storm tracked farther north, Tip was able to intensify. After passing Guam, Tip rapidly intensified and reached peak sustained winds of 305 km/h (190 mph)[nb 1] and a worldwide record-low sea-level pressure of 870 hPa (25.69 inHg) on October 12. At its peak intensity, Tip was the largest tropical cyclone on record, with a wind diameter of 2,220 km (1,380 mi). Tip slowly weakened as it continued west-northwestward and later turned to the northeast, in response to an approaching trough. The typhoon made landfall in southern Japan on October 19, and became an extratropical cyclone shortly thereafter. Tip's extratropical remnants continued moving east-northeastward, until they dissipated near the Aleutian Islands on October 24.

U.S. Air Force aircraft flew 60 weather reconnaissance missions into the typhoon, making Tip one of the most closely observed tropical cyclones.[1] Rainfall from Tip indirectly led to a fire that killed 13 United States Marines and injured 68 at Combined Arms Training Center, Camp Fuji in the Shizuoka Prefecture of Japan.[2] Elsewhere in the country, the typhoon caused widespread flooding and 42 deaths; offshore shipwrecks left 44 people killed or missing.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

At the end of September 1979, three circulations developed within the monsoon trough that extended from the Philippines to the Marshall Islands. The westernmost disturbance developed into a tropical depression on October 1, to the west of Luzon, which would later become Typhoon Sarah on October 7.[3] On October 3, the disturbance southwest of Guam developed into Tropical Storm Roger, and later on the same day, a third tropical disturbance that would later become Typhoon Tip formed south of Pohnpei. Strong flow from across the equator was drawn into Roger's wind circulation, initially preventing significant development of the precursor disturbance to Tip. Despite the unfavorable air pattern, the tropical disturbance gradually organized as it moved westward. Due to the large-scale circulation pattern of Tropical Storm Roger, Tip's precursor moved erratically and slowly executed a cyclonic loop to the southeast of Chuuk. A reconnaissance aircraft flight into the system late on October 4 confirmed the existence of a closed low-level circulation, and early on October 5, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) issued its first warning on Tropical Depression Twenty-Three-W.[1]

While executing another loop near Chuuk, the tropical depression intensified into Tropical Storm Tip, though the storm failed to organize significantly due to the influence of Tropical Storm Roger. Reconnaissance aircraft provided the track of the surface circulation, since satellite imagery estimated the center was about 60 km (37 mi) from its true position. After drifting erratically for several days, Tip began a steady northwest motion on October 8. By that time, Tropical Storm Roger had become an extratropical cyclone, resulting in the southerly flow to be entrained into Tip. An area of a tropical upper tropospheric trough moved north of Guam at the time, providing an excellent outflow channel north of Tip. Initially, Tip was predicted to continue northwestward and make landfall on Guam, though instead, it turned to the west early on October 9, passing about 45 km (28 mi) south of Guam. Later that day, Tip intensified to attain typhoon status.[1]

Owing to very favorable conditions for development, Typhoon Tip rapidly intensified over the open waters of the western Pacific Ocean. Late on October 10, Tip attained wind speeds equal to Category 4 strength on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale (SSHS), and it became a super typhoon on the next day. The central pressure dropped by 92 hPa (2.72 inHg) from October 9 to 11, during which the circulation pattern of Typhoon Tip expanded to a record diameter of 2,220 km (1,380 mi). Tip continued to intensify further, becoming a Category 5-equivalent super typhoon, and early on October 12, reconnaissance aircraft recorded a worldwide record-low pressure of 870 mbar (870.0 hPa; 25.69 inHg) with 1-minute sustained winds of 305 km/h (190 mph), when Tip was located about 840 km (520 mi) west-northwest of Guam.[1] In its best track, the Japan Meteorological Agency listed Tip as peaking with 10-minute sustained winds of 160 mph (260 km/h).[4] At the time of its peak strength, its eye was 15 km (9.3 mi) wide.[1] Tip crossed the 135th meridian east on the afternoon of October 13, prompting the PAGASA to issue warnings on Typhoon Tip, assigning it the local name Warling.[1][5]

After peaking in intensity, Tip weakened to 230 km/h (145 mph) and remained at that intensity for several days, as it continued west-northwestward. For five days after its peak strength, the average radius of winds stronger than 55 km/h (35 mph) extended over 1,100 km (684 mi). On October 17, Tip began to weaken steadily and decrease in size, recurving northeastward under the influence of a mid-level trough the next day. After passing about 65 km (40 mi) east of Okinawa, the typhoon accelerated to 75 km/h (45 mph). Tip made landfall on the Japanese island of Honshū with winds of about 130 km/h (80 mph) on October 19. It continued rapidly northeastward through the country and became an extratropical cyclone over northern Honshū a few hours after moving ashore.[1] The extratropical remnant of Tip proceeded east-northeastward and gradually weakened, crossing the International Date Line on October 22. The storm was last observed near the Aleutian Islands of Alaska on October 24.[4]

Impact

| Typhoon | Season | Pressure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hPa | inHg | |||

| 1 | Tip | 1979 | 870 | 25.7 |

| 2 | June | 1975 | 875 | 25.8 |

| Nora | 1973 | |||

| 4 | Forrest | 1983 | 876[6] | 25.9 |

| 5 | Ida | 1958 | 877 | 25.9 |

| 6 | Rita | 1978 | 878 | 26.0 |

| 7 | Kit | 1966 | 880 | 26.0 |

| Vanessa | 1984 | |||

| 9 | Nancy | 1961 | 882 | 26.4 |

| 10 | Irma | 1971 | 884 | 26.1 |

| 11 | Nina | 1953 | 885 | 26.1 |

| Joan | 1959 | |||

| Megi | 2010 | |||

| Source: JMA Typhoon Best Track Analysis Information for the North Western Pacific Ocean.[7] | ||||

The typhoon produced heavy rainfall early in its lifetime while passing near Guam, including a total of 231 mm (9.1 in) at Andersen Air Force Base.[1] Gusts of 125 km/h (80 mph) were measured during October 9 at the Naval Base Guam, as the center of the storm was positioned 70 km (43 mi) south of Agana. Tip caused a total loss of nearly US$1.6 million (1979 USD, US$6.93 million in 2024) across Guam.[8] The outer rainbands of the large circulation of Tip produced moderate rainfall in the mountainous regions of the Philippine islands of Luzon and Visayas.[9]

Heavy rainfall from the typhoon breached a flood-retaining wall at Camp Fuji, a training facility for the United States Marine Corps near Yokosuka.[10] Marines inside the camp weathered the storm inside huts situated at the base of a hill which housed a fuel farm. The breach led to hoses being dislodged from two rubber storage bladders, releasing large quantities of fuel. The fuel flowed down the hill and was ignited by a heater used to warm one of the huts.[11][12][13] The resultant fire killed 13 Marines, injured 68,[1] and caused moderate damage to the facility. The facility's barracks were destroyed,[10] along with fifteen huts and several other structures.[11][14] The barracks were rebuilt,[10] and a memorial was established for those who lost their lives in the fire.[11]

During recurvature, Typhoon Tip passed about 65 km (40 mi) east of Okinawa. Sustained winds reached 72 km/h (45 mph), with gusts to 112 km/h (70 mph). Sustained wind velocities in Japan are not known, though they were estimated at minimal typhoon strength. The passage of the typhoon through the region resulted in millions of dollars in damage to the agricultural and fishing industries of the country.[1] Eight ships were grounded or sunk by Tip, leaving 44 fishermen dead or unaccounted for. A Chinese freighter broke in half as a result of the typhoon, though its crew of 46 were rescued.[9] The rainfall led to over 600 mudslides throughout the mountainous regions of Japan and flooded more than 22,000 homes; 42 people died throughout the country, with another 71 missing and 283 injured.[9] River embankments broke in 70 places, destroying 27 bridges, while about 105 dikes were destroyed. Following the storm, at least 11,000 people were left homeless. Tip destroyed apple, rice, peach and other crops. Five ships sank in heavy seas off the coast and 50-story buildings swayed in the capital, Tokyo.[15][16] Transportation in the country was disrupted; 200 trains and 160 domestic flights were canceled.[17] In total, damages associated with Tip in Japan were estimated as ¥105.7 billion (US$482.34 million in 1979 USD, US$2.09 billion in 2024).[18] Tip was described as the most severe storm to strike Japan in 13 years.[19]

Records and meteorological statistics

Typhoon Tip was the largest tropical cyclone on record, with a diameter of 1,380 mi (2,220 km)—almost double the previous record of 700 mi (1,130 km) in diameter set by Typhoon Marge in August 1951.[20][21][22] At its largest, Tip was nearly half the size of the contiguous United States.[23] The temperature inside the eye of Typhoon Tip at peak intensity was 30 °C (86 °F) and described as exceptionally high.[1] With 10-minute sustained winds of 160 mph (260 km/h), Typhoon Tip is the strongest cyclone in the complete tropical cyclone listing by the Japan Meteorological Agency.[4]

The typhoon was also the most intense tropical cyclone on record, with a pressure of 870 mbar (25.69 inHg), 5 mbar (0.15 inHg) lower than the previous record set by Super Typhoon June in 1975.[1][24][25] The records set by Tip still technically stand, though with the end of routine reconnaissance aircraft flights in the western Pacific Ocean in August 1987, modern researchers have questioned whether Tip indeed remains the strongest. After a detailed study, three researchers determined that two typhoons, Angela in 1995 and Gay in 1992, registered higher Dvorak numbers than Tip, and concluded that one or both of the two may have therefore been more intense.[26] Other recent storms may have also been more intense than Tip at its peak; for instance, satellite-derived intensity estimates for Typhoon Haiyan of 2013 indicated that its core pressure may have been as low as 858 mbar (25.34 inHg).[27] Due to the dearth of direct observations and Hurricane hunters into these cyclones, conclusive data is lacking.[26] In October 2015, Hurricane Patricia reached an estimated peak intensity of 872 millibars (25.8 inHg), with maximum 1-minute sustained winds of 345 km/h (215 mph), making Patricia the second-most intense tropical cyclone recorded worldwide. However, the NHC noted in their report on the cyclone that Patricia may have surpassed Tip at the time of its peak intensity, as it was undergoing rapid intensification; however, due to the lack of direct aircraft observations at the time of the storm's peak, this possibility cannot be determined.[28]

Despite the typhoon's intensity and damage, the name Tip was not retired and was reused in 1983, 1986, and 1989.[4] The name was discontinued from further use in 1989, when the JTWC changed their naming list.[29]

See also

- List of tropical cyclone records

- Other notable tropical cyclones that broke records:

- Cyclone Mahina (1899) – Possibly the most intense storm recorded in the Southern Hemisphere, with a peak low pressure of 880 hPa (25.99 inHg)

- Typhoon Nancy (1961) - An extremely powerful typhoon that unofficially had the strongest winds ever recorded in a typhoon, with maximum 1-minute sustained winds at 215 mph (346 km/h), tying Hurricane Patricia

- Tropical Storm Marco (2008) – The smallest tropical cyclone on record

- Hurricane Patricia (2015) – Second-most intense tropical cyclone, most intense ever recorded in the Western Hemisphere, with the highest maximum 1-minute sustained winds recorded in a tropical cyclone, at 215 mph (346 km/h)

- Cyclone Winston (2016) - Officially the most intense storm in the Southern Hemisphere, with peak low pressure of 884 hPa (26.10 inHg). Also became the most intense landfalling tropical cyclone on record, impacting with same pressure

- Typhoon Goni (2020) – A Category 5-equivalent super typhoon that became the strongest landfalling storm on record, with 1-minute sustained winds of 195 mph (314 km/h)

- Typhoon Haiyan (2013) - The deadliest Philippine typhoon in modern history

- Cyclone Freddy (2023) - The longest lasting tropical cyclone ever recorded.

- Other notable tropical cyclones that impacted Japan:

- Typhoon Vera (1959) - The strongest storm to ever impact Japan, with maximum sustained wind speeds of 160 mph (260 km/h) upon landfall - Comparable to a Category 5-equivalent super typhoon

- Typhoon Wipha (2013) - Similar impacts and dissipation

- Typhoon Lan (2017) – Another very large and powerful typhoon

- Typhoon Jebi (2018) – A typhoon that took a slightly similar track path and struck Japan as a Category 2-equivalent typhoon; caused substantial damage, primarily in the Kansai region

- Typhoon Trami (2018) – A Category 5-equivalent super typhoon that affected the same general area

- Typhoon Hagibis (2019) – A typhoon that took almost similar track path, similar size, similar landfall date and struck Japan as a Category 2-equivalent typhoon; caused tremendous damage and marked the 40th anniversary of Tip

- Hypercane

Notes

- ^ All wind speeds in the article are maximum sustained winds sustained for one minute, unless otherwise noted.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l George M. Dunnavan; John W. Dierks (1980). "An Analysis of Super Typhoon Tip (October 1979)". Monthly Weather Review. 108 (II). Joint Typhoon Warning Center: 1915–1923. Bibcode:1980MWRv..108.1915D. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1980)108<1915:AAOSTT>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0493.

- ^ Little, Vince (2007-10-19). "Marines recall 1979 fire at Camp Fuji that claimed 13 lives". Stars and Stripes. Archived from the original on 2018-10-17. Retrieved 2016-07-25.

- ^ "1979 ATCR TABLE OF CONTENTS". Pearl Harbor, Hawaii: Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 1978. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2021-05-12.

- ^ a b c d Japan Meteorological Agency (2010-01-12). "Best Track for Western North Pacific Tropical Cyclones". Archived from the original (TXT) on 2013-06-25. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ^ "The speediest and deadliest cyclones in the world". Financial Express. 14 June 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "World Tropical Cyclone Records". World Meteorological Organization. Arizona State University. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ^ Japan Meteorological Agency. "RSMC Best Track Data (Text)" (TXT).

- ^ Tropical Cyclones Affecting Guam (1671-1990) (PDF) (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c Debi Iacovelli; Tim Vasquez (August 1998). Marthin S. Baron (ed.). "Super Typhoon Tip: Shattering all records" (PDF). Mariners Weather Log. 42 (2). Voluntary Observing Ship Project: 4–8. ISSN 0025-3367. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-11-24. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

- ^ a b c "History of the U.S. Naval Mobile Construction Battalion FOUR". U.S. Naval Construction Force. 2004. Archived from the original on 2007-02-05. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

- ^ a b c "Camp Fuji Fire Memorial". United States Marine Corps. 2006-08-03. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

- ^ "Second U.S. Marine Dies In Typhoon-Caused Fire". The Washington Post. 1979-10-20.

- ^ "Marine Killed in Japanese Typhooe [sic]". The Washington Post. 1979-10-20.

- ^ "1 Marine Killed as Typhoon Hits Facility in Japan". Palm Beach Post. 1979-10-20.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "25 are killed as Typhoon Tip crosses Japan". The Globe and Mail. Reuters. 1979-10-20.

- ^ "International News". Associated Press. 1979-10-19.

- ^ "International News". Associated Press. 1979-10-18.

- ^ "Digital Typhoon: Typhoon 197920 (TIP) - Disaster Information". Digital Typhoon Disaster Database. National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ^ "International News". Associated Press. 1979-10-22.

- ^ National Weather Service Southern Region Headquarters (2010-01-05). "Tropical Cyclone Structure". JetStream - Online School for Weather: Tropical Weather. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 2013-12-07. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ Bryan Norcross (2007). Hurricane Almanac: The Essential Guide to Storms Past, Present, and Future. St. Martin's Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-312-37152-4. Archived from the original on 2015-03-22. Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- ^ Steve Stone (2005-09-22). "Rare Category 5 hurricane is history in the making". The Virginia Pilot. Archived from the original on 2012-01-20. Retrieved 2011-12-31.

- ^ M. Ragheb (2011-09-25). "Natural Disasters and Man made Accidents" (PDF). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-26. Retrieved 2011-12-31.

- ^ Jay Barnes (2007). Florida's Hurricane History. Chapel Hill Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-8078-3068-0.

- ^ National Weather Service (2005). "Super Typhoon Tip". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved 2014-06-23.

- ^ a b Karl Hoarau; Gary Padgett; Jean-Paul Hoarau (2004). Have there been any typhoons stronger than Super Typhoon Tip? (PDF). 26th Conference on Hurricanes and Tropical Meteorology. Miami, Florida: American Meteorological Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-11-09. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ^ Satellite Services Division (2013). "Typhoon 31W". National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ Todd B. Kimberlain; Eric S. Blake; John P. Cangialosi (February 1, 2016). Hurricane Patricia (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Robert J. Plante; Charles P. Guard (6 July 1990). 1989 Annual Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF). Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

External links

Media related to Typhoon Tip at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Typhoon Tip at Wikimedia Commons