TrueType

| Filename extension | .ttf & .tte (for EUDC usage) for Microsoft Windows, .dfont for macOS |

|---|---|

| Internet media type |

|

| Type code | TFIL |

| Uniform Type Identifier (UTI) | public.truetype-ttf-font |

| Developed by | Apple |

| Type of format | outline font |

| Extended from | SFNT |

| Extended to | OpenType |

TrueType is an outline font standard developed by Apple in the late 1980s as a competitor to Adobe's Type 1 fonts used in PostScript. It has become the most common format for fonts on the classic Mac OS, macOS, and Microsoft Windows operating systems.

The primary strength of TrueType was originally that it offered font developers a high degree of control over precisely how their fonts are displayed, right down to particular pixels, at various font sizes. With widely varying rendering technologies in use today, pixel-level control is no longer certain in a TrueType font.

History

TrueType was known during its development stage, first by the codename "Bass" and later on by the codename "Royal".[2] The system was developed and eventually released as TrueType with the launch of Mac System 7 in May 1991. The initial TrueType outline fonts, four-weight families of Times Roman, Helvetica, Courier,[3] and the pi font "Symbol" replicated the original PostScript fonts of the Apple LaserWriter. Apple also replaced some of their bitmap fonts used by the graphical user-interface of previous Macintosh System versions (including Geneva, Monaco and New York) with scalable TrueType outline-fonts. For compatibility with older systems, Apple shipped these fonts, a TrueType Extension and a TrueType-aware version of Font/DA Mover for System 6. For compatibility with the Laserwriter II, Apple developed fonts like ITC Bookman and ITC Chancery in TrueType format.

All of these fonts could now scale to all sizes on screen and printer, making the Macintosh System 7 the first OS to work without any bitmap fonts. The early TrueType systems — being still part of Apple's QuickDraw graphics subsystem — did not render Type 1 fonts on-screen as they do today. At the time, many users had already invested considerable money in Adobe's still proprietary Type 1 fonts. As part of Apple's tactic of opening the font format versus Adobe's desire to keep it closed to all but Adobe licensees, Apple licensed TrueType to Microsoft. When TrueType and the license to Microsoft was announced, John Warnock, co-founder and then CEO of Adobe, gave an impassioned speech in which he claimed Apple and Microsoft were selling snake oil, and then announced that the Type 1 format was open for anyone to use.

Meanwhile, in exchange for TrueType, Apple got a license for TrueImage, a PostScript-compatible page-description language owned by Microsoft that Apple could use in laser printing. This was never actually included in any Apple products when a later deal was struck between Apple and Adobe, where Adobe promised to put a TrueType interpreter in their PostScript printer boards. Apple renewed its agreements with Adobe for the use of PostScript in its printers, resulting in lower royalty payments to Adobe, who was beginning to license printer controllers capable of competing directly with Apple's LaserWriter printers.

Part of Adobe's response to learning that TrueType was being developed was to create the Adobe Type Manager software to scale Type 1 fonts for anti-aliased output on-screen. Although ATM initially cost money, rather than coming free with the operating system, it became a de facto standard for anyone involved in desktop publishing. Anti-aliased rendering, combined with Adobe applications' ability to zoom in to read small type, and further combined with the now open PostScript Type 1 font format, provided the impetus for an explosion in font design and in desktop publishing of newspapers and magazines.

Apple extended TrueType with the launch of TrueType GX in 1994, with additional tables in the sfnt which formed part of QuickDraw GX. This offered powerful extensions in two main areas. First was font axes (today known as variations), for example allowing fonts to be smoothly adjusted from light to bold or from narrow to extended — competition for Adobe's "multiple master" technology. Second was Line Layout Manager, where particular sequences of characters can be coded to flip to different designs in certain circumstances, useful for example to offer ligatures for "fi", "ffi", "ct", etc. while maintaining the backing store of characters necessary for spell checkers and text searching. However, the lack of user-friendly tools for making TrueType GX fonts meant there were no more than a handful of GX fonts.

Much of the technology in TrueType GX, including variations and substitution, lives on as AAT (Apple Advanced Typography) in macOS. Few font-developers outside Apple attempt to make AAT fonts; instead, OpenType has become the dominant sfnt format, and all of the font variation technology is the de facto standard today in OpenType Variations.

Adoption by Microsoft

To ensure its wide adoption, Apple licensed TrueType to Microsoft for free.[4] Microsoft added TrueType into the Windows 3.1 operating environment. In partnership with their contractors, Monotype Imaging, Microsoft put a lot of effort into creating a set of high quality TrueType fonts that were compatible with the core fonts being bundled with PostScript equipment at the time. This included the fonts that are standard with Windows to this day: Times New Roman (compatible with Times Roman), Arial (compatible with Helvetica) and Courier New (compatible with Courier). In this context, "compatible" means two things. On an aesthetic level, it means that the fonts are similar in appearance. On a functional level, it means that the fonts have the same character widths. This allows documents which have been typeset in one font to be changed to the other, without reflow.

Microsoft and Monotype technicians used TrueType's hinting technology to ensure that these fonts did not suffer from the problem of illegibility at low resolutions, which had previously forced the use of bitmapped fonts for screen display. Subsequent advances in technology have introduced first anti-aliasing, which smooths the edges of fonts at the expense of a slight blurring, and more recently subpixel rendering (the Microsoft implementation goes by the name ClearType), which exploits the pixel structure of LCD based displays to increase the apparent resolution of text. Microsoft has heavily marketed ClearType, and sub-pixel rendering techniques for text are now widely used on all platforms.

Microsoft also developed a "smart font" technology, named TrueType Open in 1994, later renamed to OpenType in 1996 when it merged support of the Adobe Type 1 glyph outlines. Opentype now contains all of the same functionality of Apple TrueType and Apple TrueType GX.

Platform support

Macintosh and Microsoft Windows

TrueType has long been the most common format for fonts on classic Mac OS, Mac OS X, and Microsoft Windows, although Mac OS X and Microsoft Windows also include native support for Adobe's Type 1 format and the OpenType extension to TrueType (since Mac OS X 10.0 and Windows 2000). While some fonts provided with the new operating systems are now in the OpenType format, most free or inexpensive third-party fonts use plain TrueType.

Increasing resolutions and new approaches to screen rendering have reduced the requirement of extensive TrueType hinting. Apple's rendering approach on macOS ignores almost all the hints in a TrueType font, while Microsoft's ClearType ignores many hints, and according to Microsoft, works best with "lightly hinted" fonts.

Linux and other platforms

The FreeType project of David Turner has created an independent implementation of the TrueType standard (as well as other font standards in FreeType 2). FreeType is included in many Linux distributions.

Until May 2010, there were potential patent infringements in FreeType 1 because parts of the TrueType hinting virtual machine were patented by Apple, a fact not mentioned in the TrueType standards. (Patent holders who contribute to standards published by a major standards body such as ISO are required to disclose the scope of their patents, but TrueType was not such a standard.)[5] FreeType 2 included an optional automatic hinter to avoid the patented technology, but these patents have now expired so FreeType 2.4 now enables these features by default.[6]

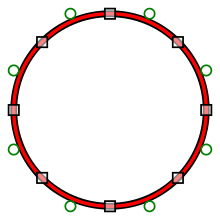

Outlines

The outlines of the characters (or glyphs) in TrueType fonts are made of straight line segments and quadratic Bézier curves. These curves are mathematically simpler and faster to process than cubic Bézier curves, which are used both in the PostScript-centered world of graphic design and in Type 1 fonts. However, most shapes require more points to describe with quadratic curves than cubics. This difference also means that it is not possible to convert Type 1 losslessly to the TrueType format, although in practice it is often possible to do a lossless conversion from TrueType to Type 1.[7][8]

Hinting language

TrueType systems include a virtual machine that executes programs inside the font, processing the "hints" of the glyphs, in TrueType called “instructions”. These distort the control points which define the outline, with the intention that the rasterizer produce fewer undesirable features on the glyph. Each glyph's instruction set takes account of the size (in pixels) at which the glyph is to be displayed, as well as other less important factors of the display environment.

Although incapable of receiving input and producing output as normally understood in programming, the TrueType instruction language does offer the other prerequisites of programming languages: conditional branching (IF statements), looping an arbitrary number of times (FOR- and WHILE-type statements), variables (although these are simply numbered slots in an area of memory reserved by the font), and encapsulation of code into functions. Special instructions called delta instructions are the lowest level control, moving a control point at just one pixel size.

The hallmark of effective TrueType glyph programming techniques is that it does as much as possible using variables defined just once in the whole font (e.g., stem widths, cap height, x-height). This means avoiding delta instructions as much as possible. This helps the font developer to make major changes (e.g., the point at which the entire font's main stems jump from 1 to 2 pixels wide) most of the way through development.

Creating a very well-instructed TrueType font remains a significant amount of work, despite the increased user-friendliness of programs for adding instructions to fonts. Many TrueType fonts therefore have only rudimentary instructions, or have them automatically applied by the font editor, with results of various quality.

Embedding protection

The TrueType format allows for the most basic type of digital rights management – an embeddable flag field that specifies whether the author allows embedding of the font file into things like PDF files and websites. Anyone with access to the font file can directly modify this field, and simple tools exist to facilitate modifying it (obviously, modifying this field does not modify the font license and does not give extra legal rights).[9][10] These tools have been the subject of controversy over potential copyright issues.[11][12]

Emoji

Apple has implemented a proprietary extension to allow color .ttf files for its emoji font Apple Color Emoji.

File formats

Basic

A basic font is composed of multiple tables specified in its header. A table name can have up to 4 letters.

A .ttf extension indicates a regular TrueType font or an OpenType font with TrueType outlines. Windows end user defined character editor (EUDCEDIT.EXE) creates TrueType font with name EUDC.TTE.[13] An OpenType font with PostScript outlines must have an .otf extension. In principle an OpenType font with TrueType outlines may have an .otf extension, but this has rarely been done in practice.

In classic Mac OS and macOS, OpenType is one of several formats referred to as data-fork fonts, as they lack the classic Mac resource fork.

Collection

TrueType Collection (TTC) is an extension of TrueType format that allows combining multiple fonts into a single file, creating substantial space savings for a collection of fonts with many glyphs in common. They were first available in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean versions of Windows, and supported for all regions in Windows 2000 and later. Classic Mac OS included support of TTC starting with Mac OS 8.5.

A TrueType Collection file begins with a ttcf table that allows access to the fonts within the collection by pointing to individual headers for each included font. The fonts within a collection share the same glyph-outline table, though each font can refer to subsets within those outlines in its own manner, through its cmap, name and loca tables. Collection files bear a .ttc filename extension. In classic Mac OS and macOS, TTC has file type ttcf.

Suitcase

The suitcase format for TrueType is used on classic Mac OS and macOS. It adds additional Apple-specific information.

Like TTC, it can handle multiple fonts within a single file. But unlike TTC, those fonts need not be within the same family.

Suitcases come in resource-fork and data-fork formats. The resource-fork version was the original suitcase format. Data-fork-only suitcases, which place the resource fork contents into the data fork, were first supported in macOS. A suitcase packed into the data-fork-only format has the extension dfont.

PostScript

In the PostScript language, TrueType outlines are handled with a PostScript wrapper as Type 42 for name-keyed or Type 11 for CID-keyed fonts.

See also

- Apple Type Services for Unicode Imaging (New Macintosh multilingual text rendering engine)

- ClearType

- Core Text

- Datafork TrueType

- Embedded TrueType font

- FreeType

- GNU FreeFont

- Graphite (SIL)

- Nonzero-rule

- Online office suite

- Open-source Unicode typefaces

- OpenType

- Pango (Open source multilingual text rendering engine)

- Typeface

- Typography

- Unicode, UTF-8, Unicode fonts.

- Uniscribe (Windows multilingual text rendering engine)

- Web Open Font Format

- WorldScript (Old Macintosh multilingual text rendering engine)

References

- ^ "Media Types". IANA. 2017-10-12. Retrieved 2017-10-17.

- ^ Jacobs, Mike (2017-10-19). "A brief history of TrueType". Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2019-05-25. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- ^ "A History of TrueType". www.truetype-typography.com. Retrieved 2020-01-08.

- ^ Gassée, Jean-Louis (11 April 2010). "The Adobe – Apple Flame War". mondaynote.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ "FreeType and Patents". Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ "The TrueType Bytecode Patents Have Expired!". FreeType & Patents. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ ""Interview: Donald E. Knuth" by advogato" (PDF).

- ^ ""Interview: Donald E. Knuth" by advogato".

- ^ "TTFPATCH — a free tool to change the embeddable flag (fsType) of TrueType fonts". Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ "Truetype embedding-enabler". Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ "Unintended Consequences: Twelve Years under the DMCA". Electronic Frontier Foundation. 3 March 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ "Truetype embedding-enabler : DMCA threats". Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ "How to create and use custom fonts for PDF generation" (PDF). apitron.com. 6 March 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2017.