Taxation in ancient Rome

There were four primary kinds of taxation in ancient Rome: a cattle tax, a land tax, customs, and a tax on the profits of any profession. These taxes were typically collected by local aristocrats. The Roman state would set a fixed amount of money each region needed to provide in taxes, and the local officials would decide who paid the taxes and how much they paid. Once collected the taxes would be used to fund the military, create public works, establish trade networks, stimulate the economy, and to fund the cursus publicum.

Types

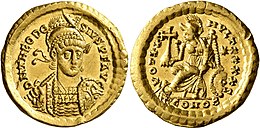

The ancient Romans had two classes of taxes: the tributa and the vectigalia.[1] Tributa included the tributum soli (a land tax) and the tributum capitis (a poll tax). The vectigalia consisted of four kinds of tax: the portoria (poll tax), the vicesima hereditatium (inheritance tax), the vicesima liberatis (postage tax), and the centesima rerum venalium (auction sales tax). Cities may have occasionally levied other taxes; however, they were usually temporary.[2] In ancient Rome there was no income tax, instead the primary tax was the portoria. This tax was imposed on goods exiting or entering the city.[3][4] The size of the tax was based on the value of the item itself. It was higher on luxurious or expensive items, but lower on basic necessities. It was abolished in 60 BCE as it was no longer needed. The Roman empire's increasing size allowed for the government to procure sufficient funds from tributaries.[5] Roman veterans were exempt from paying the portoria tax.[6] Augustus created the vicesima hereditatium and the centesima. The vicesima was an inheritance tax and the centesima was a sales tax on auctions.[7] Both policies were unpopular.[8] They were designed to fund the aerarium militare,[9] which was a service that provided money to veterans.[10] Caligula abolished the centesima rerum venalium on account of its unpopularity.[11][12] Caracalla granted Roman citizenship to all male residents of the empire, which was likely a method of increasing the taxable population of the empire.[13][14] Under Constantine, it had become difficult to pay taxes due to the continued debasement of the solidus, increasing the prevalence of payment in kind.[15]

Collection and management

Administration

Ancient Roman tax systems were regressive, they applied a heavier tax burden on lower income levels and reduced taxation on wealthier social classes.[16] In ancient Rome, taxation was primarily levied upon the provincial population who lived outside of Italy. Direct taxes on Italian land were abolished in 167 BCE and indirect taxes on certain transactions were removed in 60 BCE. The urbanized, populous, and important city of Rome possibly had greater influence on politics than the more dispersed and less prominent provincial population.[17]

Taxation in ancient Rome was decentralized, with the government preferring to leave the task of collecting taxes to local elected magistrates.[2] Typically these magistrates were wealthy landowners. During the Roman Republic finances were stored inside the temple of Saturn. Under the reign of Augustus a new institution was created: the fiscus. At first it only contained the wealth gained through taxes on Egypt; but it expanded to other sources later in Roman history. It also collected wealth from people who died without a will, half of the wealth of unclaimed property, and fines.[15]

The ancient Roman census, as administered by the censors, was important for the administration of taxes in ancient Rome. The results of their periodic census determined the amount of tax a citizen owed. They registered the value of each citizen's property, which determined the amount of property tax they had to pay.[18] In Roman Egypt, Greeks were entitled to reduced taxation compared to other people in Egypt. These Greco-Egyptian persons were likely the members of a special social group referenced in other Roman documents called hoi apo tou gymnasiou, meaning "gymnasial group." Difficulty identifying which members of the Egyptian populace were entitled to reduced taxation likely prompted a special census of these groups in the year 4 or 5 CE. Following this census, the number of gymnasial groups per nome was limited to one and future members of gymnasial groups were required to prove their genealogy.[19] The censors also participated in tax farming through their auctions; they auctioned off the space of a lustrum to the highest bidder in return for tithes and taxes.[20][21][22] Censors had similar duties to a modern minister of finance. They could impose new vectiglia,[23] sell government land,[24] and manage the budget.

The emperor Diocletian changed the method of collecting taxes in ancient Rome.[25] He replaced the local optimates with a bureaucracy. He established a new tax system known as the Capitatio-Iugatio to try to combat the rampant inflation of that time.[16] This system combined the land rents, known as iugatio, and the capitatio, which affected individuals. Under this policy, arable land was divided into different regions according to their yield and crop. All land, income, and direct taxes were merged into a single tax.[26] This policy tied the peasantry to their land, and those without land were taxed.[27] Diocletian instituted the aurum oblaticium and the aurum coronarium which taxed landowning senators. He also taxed businessmen with a new tax called the collatio lustralis. These policies contributed to an improved accounting system for the Late Roman Empire.[16]

Indiction

The indiction was a periodic reassessment for agricultural taxes and land taxes used throughout Roman history. During the Roman Republic this easement occurred every five years; later during the empire the cycle lasted 15 years, although in Roman Egypt a 14-year cycle was used. If the emperors made any change to the tax policy it usually occurred at the beginning of these cycles, and at the end it was common for the Emperors to forgive any arrears.[28]

The Chronicon Paschale, a 7th-century Greek Christian chronicle, claims that this system was established in 49 BCE by Julius Caesar, although it is also possible it began in 48 BC.[28] It also may have begun in 58 CE when Nero issued a series of tax reforms.[28][29] The earliest known event associated with this cycle was in 42 CE, when Claudius established a board of praetors to pursue arrears for it.[28][30] The cycle in Egypt only lasted fourteen years because in Egypt the liability for the poll tax began at the age of fourteen.[28]

Tax farming

Tax farming is a financial management technique in which a legal contract assigns the management of a revenue source to a third party while the original holder of the revenue stream receives fixed periodic rents from the contractor. This practice was first developed by the Romans.[31] Under their system, the Roman State reassigned the power to collect taxes to private individuals or organizations. These private groups paid the taxes for the area, and they used the products and money that could be garnered from the area to cover the outlay.[32][33] Tax farmers may have been tasked with collecting as much wealth in taxes as possible, with their only limit being the local political rulers who wanted to avoid the potential negative effects of overexploitation on future revenue.[17] During wartime, Publicani supplied the Roman military using their own personal resources. They would make profit by collecting taxes on the local populace. This tax would be collected by local municipal councils. If the council failed to fulfill the quota, a not uncommon occurrence, the fiscus would provide the publican with the uncollected quantity of wealth and place the council in debt for the expense.[34] Systems of tax farming may have proliferated in ancient Rome due to benefits it provided to the aristocracy of the ancient Roman world, who were not subject to the same high levels of taxation as the rest of the populace.[17]

By the time of the Roman Empire these private people or groups had become known as the publicani. Although Augustus limited the power of the publicani significantly,[35] the Roman government assumed control of farming indirect taxes under the Flavian dynasty. By Trajan's reign they controlled the collection of all vectigalia in all regions except Syria, Egypt and Judea.[36]

Usage and effects

Although the taxes levied upon the population, especially the poorer population, were likely very high, it seems probable that the exact amount of tax wealth which reached the state's treasury was lower than the amount collected. As the Roman empire expanded, it required more resources to maintain itself and continue growing, resulting in an increased level of taxation.[25] The Roman government would set a fixed amount of wealth each region needed to pay in taxes, while the magistrates were tasked with determining who would pay the taxes, and how much they would each pay. Certain regions, such as Egypt, paid some taxes in kind. Egyptian farmers supplied portions of their crop yield in tax to the rest of the Roman Empire,[37] where it would then be sold to the populace in other regions and therefore converted into monetary wealth.[38] Keith Hopkins, a British historian and sociologist, has argued that the ancient Roman tax economy contributed to urbanization by creating a system where natural resources were taxed in kind by Rome, supplying resources and trade to the city, and then these goods were sold to bring back wealth to the exporter. Taxpayer money was often abused in ancient Rome. Instead of funding public projects or internal improvements, it was often used for the more selfish pursuits of bureaucrats.[16] Hopkins argues that the tax collection systems of the Roman Empire funneled wealth into an aristocratic class, which was then primarily used to fund the Roman military and to maintain the luxurious lifestyle of Roman elites.[38] Emperor Julian stopped the city of Corinth from taxing the city of Argos, over which they had been given some power, and using that money to fund wild beast hunts.[16]

Throughout much of Roman history the tax burden was almost exclusively laid on the poorest people of the Empire while wealthier bureaucrats could avoid taxation. These systems may have contributed to the concentration of wealth and land in the hands of a small class of aristocrats.[16] Excessive taxation may also have limited the ability of provinces such as Egypt to provide goods to customers.[39] Tax debt was a prevalent issue in Roman Egypt. The Emperor Hadrian is recorded to have prided himself on writing off more tax debt than his predecessors. However, Julian the Apostate is recorded to have halted the practice of writing off tax debt to its disproportionately negative effects on the poorer Roman people, who had to pay more immediately than wealthier citizens.[16]

During the late Roman empire the level of taxation progressively needed to increase as the Roman empire needed to continue funding the military.[40] Most of the responsibility for taxation fell on the lower classes and especially the farmers. Bureaucrats used their position of authority to evade taxes, leaving the burden of taxation on the poorer citizens. By now, taxes consumed enough produce to risk the peasants survival.[41] Emperor Constantine refused to place the empire's revenue back into circulation, thus hurting the economy, and forcing farmers to sell their goods at low prices due to the emperor's economic policies. Preventing them from gathering the funds necessary to meet the high tax burden.[42] People who were unable to bear this burden would have agreed to become indebted to landlords in exchange for protection, effectively transforming them from free citizens into serfs.[43] The poor flocked to these estates, and as they grew the usage of money became increasingly rarer. This crippled the economy and the ability of the military to gather the necessary funds and manpower.[2] The poverty-stricken lower class often turned towards crime.[35][36]

Heavy taxation made the Roman government appear as oppressors, possibly contributing to the loss of provinces such as Africa.[42] Germanic incursions forced the emperors to lower tax rates in the year 413. The government of Rome also decreed that for five years, the tax rate of Italy was reduced by 80%. Despite these reductions, the provinces of Rome struggled to pay their taxes, and the Roman government was unable to receive the funding it needed.[44][45][46] Increased levels of inflation reduced the value of the money the government received in taxation. The difficulties in receiving proper tax funds impaired the Roman state's ability to adequately fund the army.[47] Most Late Roman tax money was used to pay off Germanic peoples.[48]

References

- ^ Southern, Pat (2007-10-01). The Roman Army: A Social and Institutional History. Oxford University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-19-804401-7.

- ^ a b c Stephens, W. Richard (1982). "The Fall of Rome Reconsidered: A Synthesis of Manpower and Taxation Arguments". Mid-American Review of Sociology. 7 (2): 49–65. JSTOR 23252728.

- ^ Smith, William (2022-06-03). A Smaller Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. DigiCat.

- ^ Workshop, Impact of Empire (Organization) (2011-05-10). Frontiers in the Roman World: Proceedings of the Ninth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Durham, 16-19 April 2009). BRILL. p. 54. ISBN 978-90-04-20119-4.

- ^ Asakura, Hironori (2003). World History of the Customs and Tariffs. World Customs Organization. pp. 53–59. ISBN 978-2-87492-021-9.

- ^ Wallace, Sherman LeRoy (2015-12-08). Taxation in Egypt from Augustus to Diocletian. Princeton University Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-4008-7922-9.

- ^ Francisco, Pina Polo (2020-07-08). The triumviral period: civil war, political crisis and socioeconomic transformations. Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza. p. 392. ISBN 978-84-1340-096-9.

- ^ Roncaglia, Carolynn E. (2018-05-15). Northern Italy in the Roman World: From the Bronze Age to Late Antiquity. JHU Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-4214-2520-7.

- ^ Smith, William (2022-05-07). A Smaller Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 82. ISBN 978-3-375-01299-1.

- ^ Richardson, J. S. (2012-03-28). Augustan Rome 44 BC to AD 14: The Restoration of the Republic and the Establishment of the Empire. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2904-6.

- ^ Roncaglia, Carolynn E. (2018-05-15). Northern Italy in the Roman World: From the Bronze Age to Late Antiquity. JHU Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-2520-7.

- ^ Mokyr, Joel (2003-10-16). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History. Oxford University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-19-028299-8.

- ^ Imrie, Alex (2018-05-29). The Antonine Constitution: An Edict for the Caracallan Empire. BRILL. p. 41. ISBN 978-90-04-36823-1.

- ^ Lavan, Myles; Ando, Clifford (2021-11-16). Roman and Local Citizenship in the Long Second Century CE. Oxford University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-19-757390-7.

- ^ a b Conti, Flavio (2003). A Profile of Ancient Rome. Getty Publications. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-0-89236-697-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g DeLorme, Charles; Isom, Stacey; Kamerschen, David (10 April 2005). "Rent seeking and taxation in the Ancient Roman Empire". Applied Economics. 37 (6): 705–711. doi:10.1080/0003684042000323591. S2CID 154784350.

- ^ a b c Monson, Andrew (2007). "Rule and Revenue in Egypt and Rome: Political Stability and Fiscal Institutions". Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung. 32 (4 (122)): 252–274. ISSN 0172-6404.

- ^ cf. Livy xxxix.44.

- ^ Monson, Andrew (2019-03-21), Vandorpe, Katelijn (ed.), "Taxation and Fiscal Reforms", A Companion to Greco‐Roman and Late Antique Egypt (1 ed.), Wiley, pp. 147–162, doi:10.1002/9781118428429.ch10, ISBN 978-1-118-42847-4, retrieved 2024-04-13

- ^ Macrobius Saturnalia i.12.

- ^ Cicero de Lege Agraria i.3, ii.21.

- ^ Cicero ad Qu. Fr. i.1 §12, In Verrem iii.7, De Natura Deorum iii.19, Varro de re rustica ii.1.

- ^ Livy xxix.37, xl.51.

- ^ Livy xxxii.7.

- ^ a b Hopkins, Keith (1980). "Taxes and Trade in the Roman Empire (200 B.C.-A.D. 400)". The Journal of Roman Studies. 70: 101–125. doi:10.2307/299558. JSTOR 299558. S2CID 162507113.

- ^ Sommerfeld, Ray M., Silvia A. Madeo, Kenneth E. Anderson, Betty R. Jackson (1992), Concepts of Taxation, Dryden Press: Fort Worth, TX

- ^ Ostrogorsky (2004), History of the Byzantine State, p. 37

- ^ a b c d e Duncan-Jones, Richard (1994). "Tax and tax-cycles". Money and Government in the Roman Empire. pp. 47–64. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511552632.005. ISBN 978-0-521-44192-6.

- ^ Tacitus, Annales 13.31, 50–51

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History 60.10.4

- ^ Howatson M. C.: Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, Oxford University Press, 1989, ISBN 0-19-866121-5

- ^ Howatson, M. C., ed. (2011). The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199548545.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-954854-5.[page needed]

- ^ Balsdon, J. P. V. D. (1965). Roman Civilization. Penguin Books. OCLC 1239786768.[page needed]

- ^ Frank, R. I. (1972). "Ammianus on Roman Taxation". The American Journal of Philology. 93 (1): 69–86. doi:10.2307/292902. ISSN 0002-9475.

- ^ a b Markel, Rita J. (2013-01-01). The Fall of the Roman Empire, 2nd Edition. Twenty-First Century Books. pp. 9, 55–56. ISBN 978-1-4677-0378-9.

- ^ a b Sidebotham, Steven E. (1986). Roman Economic Policy in the Erythra Thalassa: 30 B.C.-A.D. 217. BRILL. pp. 114, 164. ISBN 978-90-04-07644-0.

- ^ Rathbone, Dominic (1993). "Egypt, Augustus and Roman taxation". Cahiers du Centre Gustave Glotz. 4: 81–112. ISSN 1016-9008.

- ^ a b Hopkins, Keith (2002-03-15), "Rome, Taxes, Rents and Trade", The Ancient Economy, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 190–230, doi:10.1515/9781474472326-016/html, ISBN 978-1-4744-7232-6, retrieved 2024-04-12

- ^ Erdkamp, Paul (June 2014). "How modern was the market economy of the Roman world?". OEconomia (4–2): 225–235. doi:10.4000/oeconomia.399.

- ^ Jones, Doug (16 September 2021). "Barbarigenesis and the collapse of complex societies: Rome and after". PLOS ONE. 16 (9): e0254240. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1654240J. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0254240. PMC 8445445. PMID 34529697.

- ^ Heather, Peter (2006). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-19-532541-6.

- ^ a b Bury, J. B. (2015-03-05). A History of the Later Roman Empire. Cambridge University Press. pp. 302, 458. ISBN 978-1-108-08318-8.

- ^ Bagnall, Roger S. (1985). "Agricultural Productivity and Taxation in Later Roman Egypt". Transactions of the American Philological Association. 115: 289–308. doi:10.2307/284204. JSTOR 284204.

- ^ Ward-Perkins, Bryan (2006-07-12). The Fall of Rome: And the End of Civilization. OUP Oxford. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-19-162236-6.

- ^ Temin, Peter (2012). The Roman Market Economy (PDF). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4542-2. Project MUSE 36509.[page needed]

- ^ Finley, M. I. (1999). The Ancient Economy. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21946-5.[page needed]

- ^ Middleton, Guy D. (2017-06-26). Understanding Collapse. Cambridge University Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-107-15149-9.

- ^ Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009-05-12). How Rome Fell: Death of a Superpower. Yale University Press. pp. 18–97, 374. ISBN 978-0-300-15560-0.