Federal Reserve: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

rv |

|||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

The dividends paid by the Federal Reserve Banks to member banks are considered partial compensation for the lack of interest paid on member banks' required reserves held at the Federal Reserve Banks. By law, banks in the United States must maintain [[Fractional-reserve banking|fractional reserves]], most of which are kept on account at the Fed. The Federal Reserve does not pay interest on these funds. |

The dividends paid by the Federal Reserve Banks to member banks are considered partial compensation for the lack of interest paid on member banks' required reserves held at the Federal Reserve Banks. By law, banks in the United States must maintain [[Fractional-reserve banking|fractional reserves]], most of which are kept on account at the Fed. The Federal Reserve does not pay interest on these funds. |

||

The Federal Reserve System was created via the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 which "established a new central bank designed to add both flexibility and strength to the nation's financial system." The legislation provided for a system that included a number of regional Reserve Banks and a seven-member governing board. All national banks were required to join the system and other banks could join. The Reserve Banks opened for business in November 1914. Congress created [[Federal Reserve Note]]s to provide the nation with an elastic supply of currency. The notes were to be issued to Reserve Banks for subsequent transmittal to banking institutions in accordance with the needs of the public. |

|||

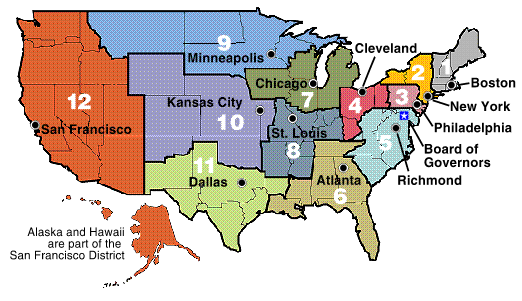

The Federal Reserve Districts are listed below along with their identifying letter and number. These are used on Federal Reserve Notes to identify the issuing bank for each note. |

The Federal Reserve Districts are listed below along with their identifying letter and number. These are used on Federal Reserve Notes to identify the issuing bank for each note. |

||

Revision as of 04:58, 26 June 2006

The Federal Reserve System (also the Federal Reserve; informally The Fed) is the central banking system of the United States.

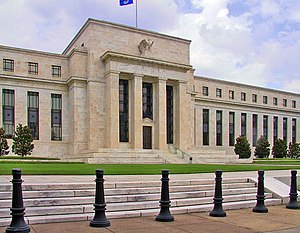

The Federal Reserve System is a quasi-governmental, decentralized central bank. It is composed of a central Board of Governors in Washington, D.C., twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks located in major cities throughout the nation, numerous member banks and other entities (see below). Ben Bernanke serves as the current Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve.

The Federal Reserve System was created via the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 which "established a new central bank designed to add both flexibility and strength to the nation's financial system." The legislation provided for a system that included a number of regional Reserve Banks and a seven-member governing board. All national banks were required to join the system and other banks could join. The Reserve Banks opened for business in November 1914. Congress created Federal Reserve Notes to provide the nation with an elastic supply of currency. The notes were to be issued to Reserve Banks for subsequent transmittal to banking institutions in accordance with the needs of the public. It includes a system of eight to twelve regional reserve banks, owned by its commercial member banks and supervised by the Federal Reserve Board. The board and its chairman are appointed by the president and approved by the Senate.

History

The first institution with responsibilities of a central bank in the U.S. was the First Bank of the United States, chartered in 1791. Later, in 1816, the Second Bank of the United States was chartered. From 1837 to 1862, in the Free Banking Era there was no formal central bank, while from 1862 to 1913, a system of national banks was instituted by the 1863 National Banking Act. A series of bank runs later provided the impetus for the creation of a more centralized banking system.

After the Panic of 1907 came close to shutting down the national banking system, bankers turned to Europe for ideas on how to implement central banking. Impetus for the System came from the voluminous reports (1909-1912) of the National Monetary Commission created by the Aldrich-Vreeland Act in 1908. Senator Nelson W. Aldrich was the Republican leader in the Senate. It took the political clout of Woodrow Wilson to get the bankers' plan passed over the objections of agrarian leader William Jennings Bryan. Wilson started with the bankers' plan that had been designed for conservative Republicans by banker Paul M. Warburg. Wilson had to outmaneuver the powerful agrarian wing of the party, led by William Jennings Bryan, which strenuously denounced banks and Wall Street. They wanted a government owned central bank which could print paper money whenever Congress wanted; Wilson convinced them that because Federal Reserve notes were obligations of the government, the plan fit their demands. Southerners and westerners learned from Wilson that that the system was decentralized into 12 districts and surely would weaken New York and strengthen the hinterlands. One key opponent Congressman Carter Glass, was given credit for the bill, and his home of Richmond, Virginia, was made a district headquarters. Powerful Senator James A. Reed of Missouri was given two district headquarters in St. Louis and Kansas City. Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act in late 1913. Wilson named Warburg and other prominent bankers to direct the new system, pleasing the bankers. The New York branch dominated the Fed and thus power remained in Wall Street. The new system began operations in 1915 and played a major role in financing the Allied and American war efforts. [Link 1956 pp 199-240]

Roles and responsibilities

The main tasks of the Federal Reserve are to:

- Supervise and regulate banks

- Implement monetary policy by open market operations, setting the discount rate, and setting the reserve ratio

- Maintain a strong payments system

- Control the amount of currency that is made and destroyed on a day to day basis (in conjunction with the Mint and Bureau of Engraving and Printing)

Other tasks include:

- Economic research

- Economic education

- Community outreach

Organization of the Federal Reserve

The basic structure of the Federal Reserve System includes:

- The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System;

- The Federal Reserve Banks;

- The member banks.

Each privately owned Federal Reserve Bank and each member bank of the Federal Reserve System is subject to oversight by a Board of Governors (see generally 12 U.S.C. § 248). The 7 members of the board are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. See 12 U.S.C. § 241. Members are selected to terms of 14 years (unless removed by the President for cause), with the ability to serve for no more than one term. See 12 U.S.C. § 242. A governor may serve the remainder of another governor's term in addition to his or her own full term.

The current members of the Board of Governors are:

- Ben Bernanke, Chairman

- Roger W. Ferguson, Jr., Vice-Chairman

- Susan Bies

- Donald Kohn

- Randall S. Kroszner

- Mark Olson

- Kevin Warsh

On February 22 2006, Vice-Chairman Roger W. Ferguson, Jr. announced his resignation effective April 28 2006.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) comprises the 7 members of the board of governors and 5 representatives selected from the Federal Reserve Banks. The representative from the 2nd District, New York, is a permanent member, while the rest of the banks rotate on two and three year intervals.

Control of the money supply

The Federal Reserve controls the size of the money supply by conducting open market operations, in which the Federal Reserve engages in the lending or purchasing of specific types of securities with authorized participants, known as the Fed's primary dealers. All Open Market Operations in the United States are conducted by the Open Market Desk at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York with an aim to making the federal funds rate as close to the target rate as possible. For a detailed look at the process by which changes to a reserve account held at the Fed affect the wider monetary supply of the economy, see money creation.

The Open Market Desk has two main tools to adjust the monetary supply, repurchase agreements and outright transactions.

To smooth temporary or cyclical changes in the monetary supply, the desk engages in repurchase agreements (repos) with its primary dealers. Repos are essentially secured, short-term lending by the Fed. On the day of the transaction, the Fed deposits money in a primary dealer’s reserve account, and receives the promised securities as collateral. When the transaction matures, the process unwinds: the Fed returns the collateral and charges the primary dealer’s reserve account for the principal and accrued interest. The term of the repo (the time between settlement and maturity) can vary from 1 day (called an overnight repo) to 65 days, though the Fed will most commonly conduct overnight and 14-day repos.

Since there is an increase of bank reserves during the term of the repo, repos temporarily increase the money supply. The effect is temporary since all repo transactions unwind, with the only lasting net effect being a slight depletion of reserves caused by the accrued interest (think one day of interest at a 4.5% annual yield, which is 0.0121% per day). The Fed has conducted repos almost daily in 2004-2005, but can also conduct reverse repos to temporarily shrink the money supply.

In a reverse repo the Fed will borrow money from the reserve accounts of primary dealers in exchange for Treasury securities as collateral. At maturity, the Fed will return the money to the reserve accounts with the accrued interest, and collect the collateral. Since this drains reserves, reverse repos temporarily contract the monetary supply, except, again, for the extremely small lasting increase caused by the accrued interest.

The other main tool available to the Open Market Desk is the outright transaction. Outrights differ from repos in that they permanently alter the money supply. Outright transactions overwhelmingly involve the purchase of Treasury securities in the secondary market.

In an outright purchase, the Fed will buy Treasury securities from primary dealers and finance these purchases by depositing newly created money in the dealer’s reserve account at the Fed. Since this operation does not unwind at the end of a set period, the resulting growth in the monetary supply is permanent. The Fed also has the authority to sell Treasuries outright, but this has been exceedingly rare since the 1980's. The sale of Treasury securities results in a permanent decrease in the money supply, as the money used as payment for the securities from the primary dealers is removed from their reserve accounts, thus working the money multiplier (see Money creation) process in reverse.

Implementation of monetary policy

Buying and selling federal government securities. When the Federal Reserve buys securities, it in effect puts more money into circulation and takes securities out of circulation. With more money around, interest rates tend to drop, and more money is borrowed and spent. When the Federal Reserve sells government securities, it in effect takes money out of circulation, causing interest rates to rise and making borrowing more difficult.

Regulating the amount of money that a member bank must keep in hand as reserves. A bank lends out most of the money deposited with it. If the Federal Reserve says that it must keep in reserve a larger fraction of its deposits, then the amount that it can lend drops, loans become harder to obtain, and interest rates rise.

Changing the interest charged to banks that want to borrow money from the federal reserve system. Banks borrow from the Federal Reserve to cover short-term needs. The interest that the Fed charges for this is called the discount rate; this will have an effect, though usually rather small, on how much money the banks will lend.

Discount rates

The Federal Reserve implements monetary policy largely by targeting the federal funds rate. This is the rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans of federal funds, which are the reserves held by banks at the Fed.

The Federal Reserve also directly sets the discount rate, which is the interest rate that banks pay the Fed to borrow directly from it. However, a bank will prefer to borrow Fed funds from another bank, rather than from the Fed at the normally higher discount rate, which might suggest problems with the bank's credit-worthiness or solvency.

Both of these rates influence the prime rate which is usually about 3 percentage points higher than the federal funds rate. The prime rate is the rate that most banks price their loans at for their best customers.

Lower interest rates stimulate economic activity by lowering the cost of borrowing, making it easier for consumers and businesses to buy and build. Higher interest rates slow the economy by increasing the cost of borrowing. (See monetary policy for a fuller explanation.)

The Federal Reserve usually adjusts the federal funds rate by 0.25% or 0.50% at a time. From early 2001 to mid 2003 the Federal Reserve lowered its interest rates 13 times, from 6.25 to 1.00%, to fight recession. In November 2002, rates were cut to 1.75, and many interest rates went below the inflation rate. (This is known as a negative real interest rate, because money paid back from a loan with an interest rate less than inflation has lower purchasing power than it had before the loan.) On June 25, 2003, the federal funds rate was lowered to 1.00%, its lowest nominal rate since July, 1958, when the overnight rate averaged 0.68%. Starting at the end of June, 2004, the Federal Reserve started to raise the target interest rate. As of May 10, 2006, the rate is at 5.00%; this is the result of sixteen 0.25% increases.

The Federal Reserve might also attempt to use open market operations to change long-term interest rates, but its "buying power" on the market is significantly smaller than that of private institutions. The Fed can also attempt to "jawbone" the markets into moving towards the Fed's desired rates, but this is not always effective.

The Federal Reserve Banks and the member banks

The twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks, which were established by the Congress as the operating arms of the nation's central banking system, are organized much like private corporations—possibly leading to some confusion about “ownership.” For example, the Reserve Banks issue shares of stock to member banks. However, owning Reserve Bank stock is quite different from owning stock in a private company. The Reserve Banks are not operated for profit, and ownership of a certain amount of stock is, by law, a condition of membership in the system. The stock may not be sold or traded or pledged as security for a loan; dividends are, by law, limited to 6% per year.[1] The largest of the Reserve Banks, in terms of assets, is the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, which is responsible for the Second District covering the state of New York, the New York City region, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

The dividends paid by the Federal Reserve Banks to member banks are considered partial compensation for the lack of interest paid on member banks' required reserves held at the Federal Reserve Banks. By law, banks in the United States must maintain fractional reserves, most of which are kept on account at the Fed. The Federal Reserve does not pay interest on these funds.

The Federal Reserve System was created via the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 which "established a new central bank designed to add both flexibility and strength to the nation's financial system." The legislation provided for a system that included a number of regional Reserve Banks and a seven-member governing board. All national banks were required to join the system and other banks could join. The Reserve Banks opened for business in November 1914. Congress created Federal Reserve Notes to provide the nation with an elastic supply of currency. The notes were to be issued to Reserve Banks for subsequent transmittal to banking institutions in accordance with the needs of the public.

The Federal Reserve Districts are listed below along with their identifying letter and number. These are used on Federal Reserve Notes to identify the issuing bank for each note.

- Boston A 1 [2]

- New York B 2 [3]

- Philadelphia C 3 [4]

- Cleveland D 4 [5]

- Richmond E 5 [6]

- Atlanta F 6 [7]

- Chicago G 7 [8]

- St Louis H 8 [9]

- Minneapolis I 9 [10]

- Kansas City J 10 [11]

- Dallas K 11 [12]

- San Francisco L 12 [13]

Legal status and position in government

The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System is an independent government agency. It is subject to laws like the Freedom of Information Act and the Privacy Act which cover Federal agencies and not private entities. Like some other independent agencies, its decisions do not have to be ratified by the President or anyone else in the executive or legislative branches of government. The Board of Governors does not receive funding from Congress, and the terms of the members of the Board span multiple presidential and congressional terms. Once a member of the Board of Governors is appointed by the president, he or she is relatively independent (although the law provides for the possibility of removal by the President "for cause" under 12 U.S.C. section 242).

In Lewis v. United States, 680 F.2d 1239 (9th Cir. 1982), the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit stated that the "Federal reserve banks are not federal instrumentalities for purposes of a Federal Torts Claims Act, but are independent, privately owned and locally controlled corporations." The opinion also stated that "the Reserve Banks have properly been held to be federal instrumentalities for some purposes."

Influence of government

Central bank independence from political control is a crucial concept in both economic theory and practice. The problem arises as central banks strive to maintain a credible commitment to price stability, when the markets know that there is political pressure to keep interest rates low. Low interest rates tend to keep unemployment below trend, encourage economic growth, and allow for cheap credit and loans. Some models however say such a policy is not sustainable without accelerating inflation in the long term. Thus, a central bank believed to be under political control cannot make a credible commitment to fight inflation, as the markets know that sitting politicians will lobby to keep rates low. This point was one of the major research topics of economist Edward C. Prescott's career. It is in this limited sense that the Federal Reserve System is independent. The members of the FOMC are not elected and do not answer to politicians in making their interest rate decisions.

The Federal Reserve is financially independent because it runs a surplus, due in part to its ownership of government bonds. In fact, it returns billions of dollars to the government each year. However, the Fed is still subject to oversight by the Congress, which periodically reviews its activities and can alter its responsibilities by statute. To further communication with Congress, the Fed delivers a report to both houses semiannually. Its independence from the executive branch was strengthened by the 1951 Accord. In general, the Federal Reserve must work within the framework of the overall objectives of economic and financial policy established by the government.

Fractional-reserve banking

In its role of setting reserve requirements for the country's banking system, the Fed regulates what is known as fractional-reserve banking. This is the common practice by banks of retaining only a fraction of their deposits to satisfy demands for withdrawals, lending the remainder at interest to obtain income that can be used to pay interest to depositors and provide profits for the banks' owners. Some people also use the term to refer to fiat money, which is money that is not backed by a tangible asset such as gold.

Fractional reserves are very easily abused and rules for these will necessarily favor certain activities in the economy very systematically over others. The United States' rules and oversight are within limits and guidelines set by the Bank for International Settlements, a banking agency which pre-dates the Bretton Woods financial and monetary system and its institutions. More recently the WTO has been regarded also as such a peer.

Criticisms of the Fed

A large and varied group of criticisms are often directed against the Federal Reserve. Some of these criticisms relate to inflation and fractional reserve banking more generally, and an in-depth treatment of these issues may be found in their respective articles. There are also specific issues relating to the chairmanship of Alan Greenspan, specifically, that the Fed’s credibility is based on a cult of personality around him and his successors. This line of argument is also more thoroughly addressed in this article. Nonetheless, critics still point to a number of specific criticisms about the methods and actions of the Fed; these are treated below.

Historical criticisms

Criticisms of the Fed are not new, and some historical criticisms are reflective of current concerns.

At one extreme are a few economists from the Austrian School and the Chicago School who want the Fed abolished. They criticize the Fed’s expansionary monetary policy in the 1920’s, allowing misallocations of capital resources and supporting a massive stock price bubble.

Milton Friedman, leader of the Chicago School argues that the Fed did not cause the Great Depression but made it worse by contracting the money supply at the very moment that markets needed liquidity. He believes the Fed should be abolished.

Opacity

Another criticism of the Federal Reserve is that it is shrouded in secrecy. Meetings are held behind closed doors, and the transcripts are released with a lag of five years. Even expert policy analysts are unsure as to the logic behind Fed decisions. Critics argue that such opacity leads to greater market volatility, as the markets must guess, often with only limited information, about how the Fed is likely to change policy in the future. The jargon-laden fence-sitting opaque style of Fed communication is often called "Fed speak." It has also been known to be standoffish in its relations with the media in an effort to maintain its carefully crafted image and resents any public information that runs contrary to this notion. A recent example occurred when MSNBC reporter Maria Bartiromo reported on MSNBC that during a conversation at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner in April of 2006, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke stated flatly "no" when asked whether the Fed was done raising interest rates. This triggered a drop in stock prices just as the market was about to close.

Additional criticism is leveled at the fact that despite its name, the Federal Reserve is not a federal government agency. As pointed out by the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in Lewis v. United States, "[e]xamining the organization and function of the Federal Reserve Banks, and applying the relevant factors, we conclude that the Reserve Banks are not federal instrumentalities for purposes of the FTCA, but are independent, privately owned and locally controlled corporations."[17]

(see e.g. [14] [15] [16]) [17]

Furthermore, the lag in the release of FOMC transcripts, as well as the extremely limited and carefully worded minutes and statement, leads to the public being unaware of the issues of major concern to the Fed, and leaves it with an inadequate understanding of the logic and rationale behind the decisions. Some argue that this is a concerted attempt to keep Congress and the public at arm’s length, but this criticism has not gained much widespread acceptance.

Legality, Opposition, and Motives of the Federal Reserve

In America: From Freedom to Fascism, film maker Aaron Russo theorizes that the popular power over the the U.S. Government has been usurped and is instead controlled by the interests of Federal Reserve through their manipulation of monetary policy and corporate banking allies. Aaron Russo then links the U.S. Federal Income Tax as a scheme for direct repayment of interest on the "debt" incurred on the "money" created "out of thin air" by the Federal Reserve. Russo further draws the lines connecting the Federal Reserve to the World Bank, World Trade Organization, and other international entities involved in controlling global monetary, and ultimately, governmental policy. This film suggests that the interests that created and own the Federal Reserve system, have an agenda based more on global economic and political domination, then on simply acting as a central bank.

In The Creature from Jekyll Island author G. Edward Griffin details how the Federal Reserve System was planned in secret by several extremely rich and powerful people for the purposes of furthering their family wealth and political power.

Economists of the Austrian School such as Ludwig von Mises contend that it is the Federal Reserve's artificial manipulation of the money supply that leads to the boom/bust business cycle that has occurred over the last century. Many economic libertarians, such as Austrian School economists, believe that the Federal Reserve's manipulation of the money supply to stop "gold flight" from England caused, or was instrumental in causing, the Great Depression. In general, laissez-faire advocates of free banking argue that there is no better judge of the proper interest rate and money supply than the market. Nobel Economist Milton Friedman says, he "prefer[s] to abolish the federal reserve system altogether."[1].

The Libertarian Party platform [18] and the Constitution Party hold positions that the Federal Reserve should be abolished on legal and economic grounds.

Further reading

- J. Lawrence Broz; The International Origins of the Federal Reserve System Cornell University Press. 1997.

- Vincent P. Carosso, "The Wall Street Trust from Pujo through Medina," Business History Review (1973) 47:421-37

- Epstein, Lita & Martin, Preston (2003). The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Federal Reserve. Alpha Books. ISBN 0028643232.

- Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960 (1963)

- Greider, William (1987). Secrets of the Temple. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671675567; nontechnical book explaining the structures, functions, and history of the Federal Reserve, focusing specifically on the tenure of Paul Volcker

- G. Edward Griffin, "The Creature from Jekyll Island: A Second Look at the Federal Reserve" (1994) ISBN 0912986212

- R.W. Hafer. The Federal Reserve System: An Encyclopedia_. Westport Greenwood Press, 2005. 451 pp, 280 entries ISBN 0-313-32839-0.

- Link, Arthur. Wilson: The New Freedom (1956) pp 199-240.

- Livingston, James. Origins of the Federal Reserve System: Money, Class, and Corporate Capitalism, 1890-1913 (1986), Marxist approach to 1913 policy

- Meltzer, Allan H. A History of the Federal Reserve, Volume 1: 1913-1951 (2004) the standard scholarly history

- Meyer, Lawrence H (2004). A Term at the Fed: An Insider's View. HarperBusiness. ISBN 0060542705; focuses on the period from 1996 to 2002, emphasizing Alan Greenspan's chairmanship during the Asian financial crisis, the stock market boom and the financial aftermath of the September 11 attacks

- Roberts, Priscilla. "'Quis Custodiet Ipsos Custodes?' The Federal Reserve System's Founding Fathers and Allied Finances in the First World War," Business History Review (1998) 72: 585-603

- Rothbard, Murray N. A History of Money and Banking in the United States: The Colonial Era to World War II (2002) libertarian who wants no Fed

- Rothbard, Murray N. (1994). The Case Against the Fed. Ludwig Von Mises Institute. ISBN 094546617X. libertarian who wants no Fed

- Bernard Shull, "The Fourth Branch: The Federal Reserve's Unlikely Rise to Power and Influence" (2005) ISBN 1567206247

- Steindl, Frank G. Monetary Interpretations of the Great Depression. (1995).

- West, Robert Craig. Banking Reform and the Federal Reserve, 1863-1923 (1977)

- Wicker, Elmus R. "A Reconsideration of Federal Reserve Policy during the 1920-1921 Depression," Journal of Economic History (1966) 26: 223-238, by economist

- Wells, Donald R. The Federal Reserve System: A History (2004)

- Wicker, Elmus. The Great Debate on Banking Reform: Nelson Aldrich and the Origins of the Fed Ohio State University Press, 2005.

- Wood, John H. A History of Central Banking in Great Britain and the United States (2005)

- Bob Woodward, Maestro: Greenspan's Fed and the American Boom (2000) popular history of Greenspan in 1990s.

Notes

- ^ Friedman and Freedom, Interview with Peter Jaworski. The Journal, Queen's University, March 15, 2002 - Issue 37, Volume 129

See also

- Reserve Bank of Australia

- Bank of Canada

- Bank of England

- Bank of Japan

- Discount window

- Economic reports

- European Central Bank

- Federal Funds

- Fort Knox Bullion Depository

- Free banking

- Gold standard

- Government debt

- Money market

- Money supply

- NESARA (National Economic Stabilization and Recovery Act) - Proposed legislation to reform the Federal Reserve System

- People's Bank of China

- Repurchase agreement

- United States dollar