Falcon 9: Difference between revisions

→Launcher versions: start cleanup/reduction of the detail on Falcon 9 v1.0 now that a separate article exists for that detail, and this article can summarize/highlight |

→Launcher versions: more copyediting to reduce detail on the F9 v1.0 |

||

| Line 88: | Line 88: | ||

All Falcon 9 vehicles are [[Two-stage-to-orbit|two-stage]], [[Liquid oxygen|LOX]]/[[RP-1]]-powered launch vehicles. |

All Falcon 9 vehicles are [[Two-stage-to-orbit|two-stage]], [[Liquid oxygen|LOX]]/[[RP-1]]-powered launch vehicles. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

SpaceX uses multiple redundant [[:Category:Avionics computers|flight computer]]s in a [[fault-tolerant design]]. Each Merlin engine is controlled by three [[Voting logic|voting]] computers, each of which has two physical processors that constantly check each other. The software runs on [[Linux]] and is written in [[C++]].<ref name=aw20121118/> |

SpaceX uses multiple redundant [[:Category:Avionics computers|flight computer]]s in a [[fault-tolerant design]]. Each Merlin engine is controlled by three [[Voting logic|voting]] computers, each of which has two physical processors that constantly check each other. The software runs on [[Linux]] and is written in [[C++]].<ref name=aw20121118/> |

||

| Line 93: | Line 97: | ||

For flexibility, [[commercial off-the-shelf]] parts and system-wide "radiation-tolerant" design are used instead of [[radiation hardening|rad-hardened]] parts.<ref name=aw20121118> |

For flexibility, [[commercial off-the-shelf]] parts and system-wide "radiation-tolerant" design are used instead of [[radiation hardening|rad-hardened]] parts.<ref name=aw20121118> |

||

{{cite news |last=Svitak|first=Amy |title=Dragon's "Radiation-Tolerant" Design |url=http://www.aviationweek.com/Blogs.aspx?plckBlogId=Blog%3a04ce340e-4b63-4d23-9695-d49ab661f385&plckPostId=Blog%3a04ce340e-4b63-4d23-9695-d49ab661f385Post%3aa8b87703-93f9-4cdf-885f-9429605e14df |accessdate=2012-11-22 |newspaper=Aviation Week |date=2012-11-18 }}</ref> |

{{cite news |last=Svitak|first=Amy |title=Dragon's "Radiation-Tolerant" Design |url=http://www.aviationweek.com/Blogs.aspx?plckBlogId=Blog%3a04ce340e-4b63-4d23-9695-d49ab661f385&plckPostId=Blog%3a04ce340e-4b63-4d23-9695-d49ab661f385Post%3aa8b87703-93f9-4cdf-885f-9429605e14df |accessdate=2012-11-22 |newspaper=Aviation Week |date=2012-11-18 }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | {{cite news |last=Klotz|first=Irene |title=Musk Says SpaceX Being "Extremely Paranoid" as It Readies for Falcon 9’s California Debut |url=http://www.spacenews.com/article/launch-report/37094musk-says-spacex-being-%E2%80%9Cextremely-paranoid%E2%80%9D-as-it-readies-for-falcon-9%E2%80%99s |accessdate=2013-09-13 |newspaper=Space News |date=2013-09-06 }}</ref> |

||

=== Falcon 9 v1.0 === |

=== Falcon 9 v1.0 === |

||

{{main|Falcon 9 v1.0}} |

{{main|Falcon 9 v1.0}} |

||

The first version of the Falcon 9 launch vehicle, Falcon 9 v1.0, was developed in 2005–2010, and was launched for the first time in 2010. Falcon 9 v1.0 made five flights in 2010–2013, |

The first version of the Falcon 9 launch vehicle, Falcon 9 v1.0, was developed in 2005–2010, and was launched for the first time in 2010. Falcon 9 v1.0 made five flights in 2010–2013, after which it was retired. |

||

==== First stage ==== |

|||

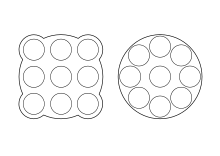

[[File:Falcon 9 v1.0 and v1.1 engine.svg|thumb|left|Falcon 9 v1.0 (left) and v1.1 (right) engine configurations]] |

[[File:Falcon 9 v1.0 and v1.1 engine.svg|thumb|left|Falcon 9 v1.0 (left) and v1.1 (right) engine configurations]] |

||

[[File:SpaceX factory Falcon 9 booster tank.jpg|thumb|350px|Falcon 9 booster tank at the SpaceX factory, 2008]] |

[[File:SpaceX factory Falcon 9 booster tank.jpg|thumb|350px|Falcon 9 booster tank at the SpaceX factory, 2008]] |

||

The Falcon 9 v1.0 first stage was |

The Falcon 9 v1.0 first stage was powered by nine SpaceX [[Merlin (rocket engine)#Merlin 1C|Merlin 1C]] rocket engines arranged in a 3x3 pattern. Each of these engines had a sea-level thrust of {{convert|556|kN|abbrev=in}} for a total thrust on liftoff of about {{convert|5000|kN|abbrev=in}}.<ref name="sxf9o20100508" /> |

||

The Falcon 9 v1.0 second stage was powered by a single [[Merlin 1C vacuum|Merlin 1C engine modified for vacuum operation]], with an [[expansion ratio]] of 117:1 and a nominal burn time of 345 seconds. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

==== Second stage ==== |

|||

The upper stage was powered by a single [[Merlin (rocket engine family)#Merlin Vacuum .281C.29|Merlin 1C engine modified for vacuum operation]], with an [[expansion ratio]] of 117:1 and a nominal burn time of 345 seconds. For added reliability of restart, the engine has dual redundant [[Pyrophoricity|pyrophoric]] igniters (TEA-TEB),<ref name="sxf9o20100508" /> and insulated propellant lines were added to the Falcon 9 v1.1 design to support in-space restart following long coast phases for orbital trajectory maneuvers.<ref name=aw20131124/><!-- this was a fix following a restart failure on the first F9 v1.1 flight in Sep 2013 --> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | {{cite news |last=Klotz|first=Irene |title=Musk Says SpaceX Being "Extremely Paranoid" as It Readies for Falcon 9’s California Debut |url=http://www.spacenews.com/article/launch-report/37094musk-says-spacex-being-%E2%80%9Cextremely-paranoid%E2%80%9D-as-it-readies-for-falcon-9%E2%80%99s |accessdate=2013-09-13 |newspaper=Space News |date=2013-09-06 }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Four [[Draco (rocket engine family)|Draco]] thrusters were used on the Falcon 9 v1.0<!-- the date of the source indicates it only supports a claim about the v1.0 version of the rocket --> second-stage as a [[reaction control system]].<ref name=sxF9LVPUG2009/> |

Four [[Draco (rocket engine family)|Draco]] thrusters were used on the Falcon 9 v1.0<!-- the date of the source indicates it only supports a claim about the v1.0 version of the rocket --> second-stage as a [[reaction control system]].<ref name=sxF9LVPUG2009/> |

||

| Line 123: | Line 120: | ||

and in 2011 SpaceX began a formal and funded [[New product development|development program]] for a [[SpaceX reusable rocket launching system|reusable Falcon 9 second stage]], with the early program focus however on return of the first stage.<ref name=pm20120207> |

and in 2011 SpaceX began a formal and funded [[New product development|development program]] for a [[SpaceX reusable rocket launching system|reusable Falcon 9 second stage]], with the early program focus however on return of the first stage.<ref name=pm20120207> |

||

{{cite news |last=Simberg|first=Rand |title=Elon Musk on SpaceX’s Reusable Rocket Plans |url=http://www.popularmechanics.com/science/space/rockets/elon-musk-on-spacexs-reusable-rocket-plans-6653023 |newspaper=Popular Mechanics |date=2012-02-08 |accessdate=2013-03-08 }}</ref> |

{{cite news |last=Simberg|first=Rand |title=Elon Musk on SpaceX’s Reusable Rocket Plans |url=http://www.popularmechanics.com/science/space/rockets/elon-musk-on-spacexs-reusable-rocket-plans-6653023 |newspaper=Popular Mechanics |date=2012-02-08 |accessdate=2013-03-08 }}</ref> |

||

=== Falcon 9 v1.1 === |

=== Falcon 9 v1.1 === |

||

| Line 148: | Line 144: | ||

{{cite web |title=Landing Legs |url=http://www.spacex.com/news/2013/03/26/landing-leg |date=2013-07-29 |publisher=SpaceX News |accessdate=2013-07-30 |quote=''The Falcon 9 first stage carries landing legs which will deploy after stage separation and allow for the rocket’s soft return to Earth. The four legs are made of state-of-the-art carbon fiber with aluminum honeycomb. Placed symmetrically around the base of the rocket, they stow along the side of the vehicle during liftoff and later extend outward and down for landing.''}}</ref> |

{{cite web |title=Landing Legs |url=http://www.spacex.com/news/2013/03/26/landing-leg |date=2013-07-29 |publisher=SpaceX News |accessdate=2013-07-30 |quote=''The Falcon 9 first stage carries landing legs which will deploy after stage separation and allow for the rocket’s soft return to Earth. The four legs are made of state-of-the-art carbon fiber with aluminum honeycomb. Placed symmetrically around the base of the rocket, they stow along the side of the vehicle during liftoff and later extend outward and down for landing.''}}</ref> |

||

which will be used only for [[SpaceX reusable rocket launching system#Falcon 9 booster post-mission.2C controlled-descent tests|post-mission technology development testing]] in the early [[Falcon 9 v1.1]] flights while supporting full [[VTVL|vertical-landing]] capability in later flights once the technology is fully developed.<ref name=nsw20130328/><ref name=pa20120328/> |

which will be used only for [[SpaceX reusable rocket launching system#Falcon 9 booster post-mission.2C controlled-descent tests|post-mission technology development testing]] in the early [[Falcon 9 v1.1]] flights while supporting full [[VTVL|vertical-landing]] capability in later flights once the technology is fully developed.<ref name=nsw20130328/><ref name=pa20120328/> |

||

Following the September 2013 launch, the second stage igniter propellant lines were insulated to better support in-space restart following long coast phases for orbital trajectory maneuvers.<ref name=aw20131124/><!-- this was a fix following a restart failure on the first F9 v1.1 flight in Sep 2013 --> |

|||

====Payload fairing==== |

====Payload fairing==== |

||

Revision as of 12:48, 29 November 2013

A Falcon 9 v1.0 launches with an uncrewed Dragon spacecraft | |

| Function | Orbital launch vehicle |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | SpaceX |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Cost per launch | v1.1: $56.5M[1] v1.0: $54M - $59.5M[2] |

| Size | |

| Height | v1.1: 68.4 m (224 ft)[3] v1.0: 54.9 m (180 ft)[2] |

| Diameter | 3.66 m (12.0 ft) |

| Mass | v1.1: 505,846 kg (1,115,200 lb)[3] v1.0: 333,400 kg (735,000 lb)[2] |

| Stages | 2 |

| Capacity | |

| Payload to LEO | v1.1: 13,150 kg (28,990 lb)[1][3] v1.0: 10,450 kg (23,040 lb)[2] |

| Payload to GTO | v1.1: 4,850 kg (10,690 lb)[1][3] v1.0: 4,540 kg (10,010 lb)[2] |

| Launch history | |

| Status | V1.1: Active v1.0: Retired |

| Launch sites | Cape Canaveral SLC-40 Vandenberg SLC-4E |

| Total launches | 6 (v1.1: 1, v1.0: 5) |

| Success(es) | 5 (v1.1: 1, v1.0: 4) |

| Partial failure(s) | 1 (v1.0) |

| First flight | v1.1: September 29, 2013[4] v1.0: June 4, 2010[5] |

| First stage | |

| Engines | v1.1: 9 Merlin 1D[3] v1.0: 9 Merlin 1C[2] |

| Thrust | v1.1: 5,885 kN (1,323,000 lbf) v1.0: 4,940 kN (1,110,000 lbf) |

| Specific impulse | v1.1 Sea level: 282 s[6] Vacuum: 311 s v1.0 Sea level: 275 s Vacuum: 304 s |

| Burn time | v1.1: 180 seconds v1.0: 170 seconds |

| Propellant | LOX/RP-1 |

| Second stage | |

| Engines | v1.1: 1 Merlin Vacuum (1D) v1.0: 1 Merlin Vacuum (1C) |

| Thrust | v1.1: 801 kN (180,000 lbf) v1.0: 445 kN (100,000 lbf) |

| Specific impulse | Vacuum: 342 s [7] |

| Burn time | v1.1: 375 seconds v1.0: 345 seconds |

| Propellant | LOX/RP-1 |

Falcon 9 is a family of rocket-powered spaceflight launch vehicles designed and manufactured by SpaceX, headquartered in Hawthorne, California. It is currently the only active rocket of the Falcon rocket family. The family consists of the Falcon 9 v1.0, Falcon 9 v1.1, and the Falcon 9-R.

Both stages of this two-stage-to-orbit vehicle use liquid oxygen (LOX) and rocket-grade kerosene (RP-1) propellants. The current Falcon 9 can lift payloads of 13,150 kilograms (28,990 lb) to low Earth orbit, and 4,850 kilograms (10,690 lb) to geostationary transfer orbit, which places the version 1.1 Falcon 9 design in the medium-lift range of launch systems.

The Falcon 9 and Dragon capsule combination won a Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) contract from NASA to resupply the International Space Station (ISS) under the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) program. The first commercial resupply mission to the International Space Station launched on October 7, 2012. Falcon 9 will also be human-rated for transporting astronauts under NASA's CCDev program.

SpaceX has developed a new and 60 percent larger launch vehicle—the Falcon 9 v1.1—which flew for the first time on a demonstration mission on the sixth overall launch of the Falcon 9 on September 29, 2013.[8]

Development and production

Funding

While SpaceX spent its own money to develop the previous launcher, the Falcon-1, the development of the Falcon-9 was accelerated by the purchase of several demonstration flights by NASA. This started with seed money from the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) program in 2006.[9] Without the NASA money, development would have taken longer, Musk said.

SpaceX estimated that development costs are on the order of $300 million.[10] NASA evaluated them using a traditional cost-plus contract approach initially at $3.6 billion.[11]

Production and testing history

The original NASA COTS contract called for the first demonstration flight of Falcon in September 2008, and completion of all three demonstration missions by September 2009.[12] In February 2008, the plan for the first Falcon 9/Dragon COTS Demo flight was delayed by six months to late in the first quarter of 2009. According to Elon Musk, the complexity of the development work and the regulatory requirements for launching from Cape Canaveral contributed to the delay.[13]

The first multi-engine test (with two engines connected to the first stage, firing simultaneously) was successfully completed in January 2008,[14] with successive tests leading to the full Falcon 9 complement of nine engines test fired for a full mission length (178 seconds) of the first stage on November 22, 2008.[15] In October 2009, the first flight-ready first stage had a successful all-engine test fire at the company's test stand in McGregor, TX. In November 2009 Space X conducted the initial second stage test firing lasting forty seconds. This test succeeded without aborts or recycles. On January 2, 2010, a full-duration (329 seconds) orbit-insertion firing of the Falcon 9 second stage was conducted at the McGregor test site[citation needed] The full stack arrived at the launch site for integration at the beginning of February 2010, and SpaceX initially scheduled a launch date of March 22, 2010, though they estimated anywhere between one and three months for integration and testing.[16]

On February 25, 2010, SpaceX's first flight stack was set vertical at Space Launch Complex 40, Cape Canaveral,[17] and on March 9, SpaceX performed a static fire test, where the first stage was to be fired without taking off. The test aborted at T-2 seconds due to a failure in the system designed to pump high-pressure helium from the launch pad into the first stage turbopumps, which would get them spinning in preparation for launch. Subsequent review showed that the failure occurred when a valve didn't receive a command to open. As the problem was with the pad and not with the rocket itself, it didn't occur at the McGregor test site, which didn't have the same valve setup. Some fire and smoke were seen at the base of the rocket, leading to speculation of an engine fire. However, the fire and smoke were the result of normal burnoff from the liquid oxygen and fuel mix present in the system prior to launch, and no damage was sustained by the vehicle or the test pad. All vehicle systems leading up to the abort performed as expected, and no additional issues were noted that needed addressing. A subsequent test on March 13 was successful in firing the nine first-stage engines for 3.5 seconds.[18]

The first flight was delayed from March 2010 to June due to review of the Falcon 9 flight termination system by the Air Force.

The first actual launch attempt occurred at 1:30 pm EDT on Friday, June 4, 2010 (1730 UTC). The launch was aborted shortly after ignition, and the rocket successfully went through a failsafe abort.[19] Ground crews were able to recycle the rocket, and successfully launched it at 2:45 pm EDT (1845 UTC) the same day.[20]

The second Falcon 9 launch, and first COTS demo flight, lifted off on December 8, 2010.[21]

The second version of the Falcon 9—Falcon 9 v1.1—was developed in 2010-2013, and launched for the first time in September 2013.

In December 2010, the SpaceX production line was manufacturing one new Falcon 9 (and Dragon spacecraft) every three months, with a plan to double to one every six weeks.[22] By September 2013, SpaceX total manufacturing space had increased to nearly 1,000,000 square feet (93,000 m2) and the factory had been configured to achieve a production rate of up to 40 rocket cores per year.[23] The November 2013 production rate for Falcon 9 vehicles was one per month. The company has stated that this will increase to 18 per year in mid-2014, and will be 24 launch vehicles per year by the end of 2014.[24]

Launcher versions

There are presently two versions of the Falcon 9. The original Falcon 9 flew five successful orbital launches in 2010–2013, and the much larger Falcon 9 v1.1 made its first flight—a demonstration mission with a very small 500 kilograms (1,100 lb) primary payload that was manifested at a "cut rate price" due to the demo mission nature of the flight[25]—on September 29, 2013.

In addition, a reusable first stage is under development for the Reusable Falcon 9 launch vehicle, with initial atmospheric testing being conducted on the Grasshopper experimental technology-demonstrator reusable launch vehicle (RLV).[26]

Common design elements

All Falcon 9 vehicles are two-stage, LOX/RP-1-powered launch vehicles.

The Falcon 9 tank walls and domes are made from aluminum lithium alloy. SpaceX uses an all-friction stir welded tank, the highest strength and most reliable welding technique available.[27]

The second stage tank of a Falcon 9 is simply a shorter version of the first stage tank and uses most of the same tooling, material and manufacturing techniques. This saves money during vehicle production.[27]

SpaceX uses multiple redundant flight computers in a fault-tolerant design. Each Merlin engine is controlled by three voting computers, each of which has two physical processors that constantly check each other. The software runs on Linux and is written in C++.[28]

For flexibility, commercial off-the-shelf parts and system-wide "radiation-tolerant" design are used instead of rad-hardened parts.[28] Both stages use a pyrophoric mixture of triethylaluminum-triethylborane (TEA-TEB) as an engine ignitor.[29]

The Falcon 9 interstage, which connects the upper and lower stage for Falcon 9, is a carbon fiber aluminum core composite structure. Reusable separation collets and a pneumatic pusher system separate the stages. The original design stage separation system had twelve attachment points, which was reduced to just three in the v1.1 launcher.[25]

Falcon 9 v1.0

The first version of the Falcon 9 launch vehicle, Falcon 9 v1.0, was developed in 2005–2010, and was launched for the first time in 2010. Falcon 9 v1.0 made five flights in 2010–2013, after which it was retired.

The Falcon 9 v1.0 first stage was powered by nine SpaceX Merlin 1C rocket engines arranged in a 3x3 pattern. Each of these engines had a sea-level thrust of 556 kilonewtons (125,000 lbf)* for a total thrust on liftoff of about 5,000 kilonewtons (1,100,000 lbf)*.[27]

The Falcon 9 v1.0 second stage was powered by a single Merlin 1C engine modified for vacuum operation, with an expansion ratio of 117:1 and a nominal burn time of 345 seconds.

Four Draco thrusters were used on the Falcon 9 v1.0 second-stage as a reaction control system.[30] The thrusters are used to hold a stable attitude for payload separation or, as a non-standard service, can be used to spin up the stage and payload to a maximum of 5 rotations per minute (RPM).[30][needs update]

Early on, SpaceX expressed hopes that both stages would eventually be reusable,[31] and in 2011 SpaceX began a formal and funded development program for a reusable Falcon 9 second stage, with the early program focus however on return of the first stage.[32]

Falcon 9 v1.1

The Falcon 9 v1.1 is a 60 percent heavier rocket with 60 percent more thrust than the v1.0 version of the Falcon 9.[25] It includes realigned first-stage engines[33] and 60 percent longer fuel tanks, making it more susceptible to bending during flight.[25] The engines themselves have been upgraded to the more powerful Merlin 1D. These improvements will increase the payload capability from 9,000 kilograms (20,000 lb) to 13,150 kilograms (28,990 lb).[34] The stage separation system has been redesigned and reduces the number of attachment points from twelve to three,[25] and the vehicle has upgraded avionics and software as well.[25] The new first stage will also be used as side boosters on the Falcon Heavy launch vehicle.[35]

The Falcon 9 v1.1, first launched on September 29, 2013, uses a longer (68.4 metres (224 ft)) first stage powered by nine Merlin 1D engines arranged in an "octagonal" pattern.[36][37] Development testing of the v1.1 Falcon 9 first stage was completed in July 2013.[38][39] The v1.1 first stage has a total sea-level thrust at liftoff of 5,885 kilonewtons (1,323,000 lbf)*, with the nine engines burning for a nominal 180 seconds, while stage thrust rises to 6,672 kilonewtons (1,500,000 lbf)* as the booster climbs out of the atmosphere.[40]

The v1.1 booster version arranges the engines in a structural form SpaceX calls Octaweb, aimed at streamlining the manufacturing process,[41] and will eventually include four extensible landing legs,[42] which will be used only for post-mission technology development testing in the early Falcon 9 v1.1 flights while supporting full vertical-landing capability in later flights once the technology is fully developed.[43][44]

Following the September 2013 launch, the second stage igniter propellant lines were insulated to better support in-space restart following long coast phases for orbital trajectory maneuvers.[24]

Payload fairing

The sixth flight (CASSIOPE, 2013) was the first launch of the Falcon 9 configured with a jettisonable payload fairing, which introduced an additional separation event – a risky operation that has doomed many previous government and commercial launch missions,[45] including the 2009 Orbiting Carbon Observatory and 2011 Glory satellite, both on Taurus rockets.

Fairing design was done by SpaceX, with production of the 13 m (43 ft)-long, 5.2 m (17 ft)-diameter payload fairing done in Hawthorne, California at the SpaceX rocket factory. Since the first five Falcon 9 launches had a capsule and did not carry a large satellite, no fairing was required on those flights. It was required on the CASSIOPE flight, as with most satellites, in order to protect the payload during launch. Testing of the new fairing design was completed at NASA's Plum Brook Station test facility in spring 2013 where the acoustic shock and mechanical vibration of launch, plus electromagnetc static discharge conditions, were simulated on a full-size fairing test article in a very large vacuum chamber. SpaceX paid NASA US$581,300 to lease test time in the $150 million NASA simulation chamber facility.[45] The fairing separated without incident during the launch of CASSIOPE.

Falcon 9-R

A third version of the rocket is in development. The Falcon 9-R, a reusable variant of the Falcon 9 is being developed using systems and software tested on the Grasshopper technology demonstrator, as well as a set of technologies being developed by SpaceX to facilitate rapid reusability of both the first and second stages.[46]

While the differences between the Falcon 9 v1.0 and the Falcon 9 v1.1 were significant, there are a much smaller set of differences between the Falcon 9 v1.1 and the emerging design of the Falcon 9-R. While no changes in rocket length or thrust are planned, the principal visible change will be the presence of extensible landing legs on the lower portion of the first-stage booster in the F9-R.[47] Additional changes will be less visible, including changes to the attitude control technology for the rocket and guidance control system software changes to regularly and reliably effect a ground landing.

Comparison

| Version | Falcon 9 v1.0 | Falcon 9 v1.1[35] |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | 9 × Merlin 1C | 9 × Merlin 1D |

| Stage 2 | 1 × Merlin 1C Vacuum | 1 × Merlin 1D Vacuum |

| Max height (m) | 53[35] | 69.2 (227 ft) |

| Diameter (m) | 3.6[48] | 3.6 |

| Initial thrust (kN) | 3,807 | 5,880 |

| Takeoff weight (tonnes) | 318[35] | 480 |

| Fairing diameter (inner; m) | * | 3.6 or 5.2 (large fairing) |

| Payload to LEO (kg) | 8,500–9,000 kg (launch at Cape Canaveral)[35] | 13,150 kg (launch at Cape Canaveral)[34] |

| Payload to GTO (kg) | 3,400[35] | 4,850[34] |

| Price (Mil. USD) | 56.5[34] | |

| Minimal cost to LEO (USD/kg) | 4,109[49][needs update] | |

| Minimal cost to GTO (USD/kg) | ||

| Complete success ratio | 4/5 | 1/1 |

| Partial success ratio | 1/5 (Secondary payload problem) (Primary payload success was 5/5) |

0/1 |

| Total loss ratio | 0/5 | 0/1 |

* = The Falcon 9 v1.0 only launched the Dragon spacecraft; it never used the payload fairing, only a nose cap.

Features

Reliability

The reliability of the Falcon-9 will not be established until the vehicle has a significant launch record. The company has predicted that it will have high reliability based on the philosophy that "through simplicity, reliability and low cost can go hand-in-hand,"[50] but this remains to be shown. As a comparison, the Russian Soyuz series has more than 1,700 launches to its credit, far more than any other rocket.[51] 75% of current launch vehicles have had at least one failure in the first three flights.[52]

After the successful launch of the CRS-2 mission on March 1, 2013, Falcon 9 v1.0 boasts a perfect record: five successful launches in five tries. Future launches of the rocket will be in the v1.1 configuration.

As with the company's smaller Falcon 1 vehicle, Falcon 9's launch sequence includes a hold-down feature that allows full engine ignition and systems check before liftoff. After first stage engine start, the launcher is held down and not released for flight until all propulsion and vehicle systems are confirmed to be operating normally. Similar hold-down systems have been used on other launch vehicles such as the Saturn V[53] and Space Shuttle. An automatic safe shut-down and unloading of propellant occurs if any abnormal conditions are detected.[27]

Falcon 9 has triple redundant flight computers and inertial navigation, with a GPS overlay for additional orbit insertion accuracy.[27]

Engine-out capability

Like the Saturn series from the Apollo program, the presence of multiple first stage engines can in principle allow for mission completion even if one of the first-stage engines fails mid-flight.[27][54] Detailed descriptions of several aspects of destructive engine failure modes and designed-in engine-out capabilities were made public by SpaceX in a 2007 "update" that was publicly released.[55]

SpaceX emphasized over several years that the Falcon 9 first stage is designed for engine out capability.[56] The SpaceX CRS-1 mission was a partial success after an engine failure in the first stage: The primary payload was inserted into the correct orbit, but due to contractual requirements of the primary payload customer, NASA, the second firing of the Falcon 9 upper stage was not allowed to insert the secondary payload into a higher orbit. This risk was understood by the secondary payload customer at time of the signing of the launch contract. As a result, the secondary payload satellite reentered atmosphere a few days after launch.[57]

In detail, the first stage experienced a loss of pressure in, and then shut down, engine no. 1 at 79 seconds after its October 2012 launch. To compensate for the resulting loss of acceleration, the first stage had to burn 28 seconds longer than planned, and the second stage had to burn an extra 15 seconds.[58][unreliable source?] That extra burn time of the second stage reduced its fuel reserves, so that the likelihood that the fuel would suffice to reach the planned orbit above the space station with the secondary payload dropped from 99% to 95%. Because the safety of the ISS was a priority, NASA declined SpaceX the right to restart the second stage and attempt to deliver the secondary payload into the correct orbit. The secondary payload was lost in earth's atmosphere a few days after launch, and was therefore considered a loss.[57]

Reusability

Although the first stages of several early Falcon flights were equipped with parachutes and were intended to be recovered to assist engineers in designing for future reusability, SpaceX was not successful in recovering the stages from the initial test launches using the original approach.[31] The Falcon boosters did not survive post separation aerodynamic stress and heating. Although reusability of the second stage is more difficult, SpaceX intended from the beginning to eventually make both stages of the Falcon 9 reusable.[59]

Both stages in the early launches were covered with a layer of ablative cork and possessed parachutes to land them gently in the sea. The stages were also marinized by salt-water corrosion resistant material, anodizing and paying attention to galvanic corrosion.[59] In early 2009, Musk stated:

"By [Falcon 1] flight six we think it’s highly likely we’ll recover the first stage, and when we get it back we’ll see what survived through re-entry, and what got fried, and carry on with the process. ... That's just to make the first stage reusable, it'll be even harder with the second stage – which has got to have a full heatshield, it'll have to have deorbit propulsion and communication."[31]

While many commentators[who?] are skeptical about reusability, Musk has said that if the vehicle does not become reusable, "I will consider us to have failed.”[60]

In late 2011, SpaceX announced a change in the approach, ditching the parachutes and going with a propulsively-powered-descent approach. On September 29, 2011, at the National Press Club, Musk indicated the initiation of a privately funded program to develop powered descent and recovery of both Falcon 9 stages – a fully vertical takeoff, vertical landing (VTVL) rocket.[61][62] Included was a video[63] said to be an approximation depicting the first stage returning tail-first for a powered descent and the second stage, with heat shield, reentering head first before rotating for a powered descent.[62][64]

Design was complete on the system for "bringing the rocket back to launchpad using only thrusters" in February 2012.[32] The reusable launch system technology is under consideration for both the Falcon 9 and the Falcon Heavy, and is considered particularly well suited to the Falcon Heavy where the two outer cores separate from the rocket much earlier in the flight profile, and are therefore moving at slower velocity at stage separation.[32]

A reusable first stage is now being flight tested by SpaceX with the suborbital Grasshopper rocket.[65] By April 2013, a low-altitude, low-speed demonstration test vehicle, Grasshopper v1.0, had made five VTVL test flights including a 80-second hover flight to an altitude of 744 metres (2,441 ft).

In March 2013, SpaceX announced that, beginning with the first flight of the stretch version of the Falcon 9 launch vehicle—the sixth flight overall of Falcon 9, currently scheduled for late September 2013—every first stage would be instrumented and equipped as a controlled descent test vehicle. SpaceX intends to do propulsive-return over-water tests and "will continue doing such tests until they can do a return to the launch site and a powered landing. ... [They] expect several failures before they 'learn how to do it right.'"[43] For the early-fall 2013 flight, after stage separation, the first stage booster will do a burn to slow it down and then a second burn just before it reaches the water. When all of the over-water testing is complete, they intend to fly back to the launch site and land propulsively, perhaps as early as mid-2014.[43][44] SpaceX has been explicit that they do not expect a successful recovery in the first several powered-descent tests. [44]

Photos of the first test of the restartable ignition system for the reusable Falcon 9—the Falcon 9-R— nine-engine v1.1 circular- engine configuration were released in April 2013.[66]

Post-mission high-altitude launch vehicle testing of Falcon 9 v1.1 boosters

The post-mission test plan calls for the first stage booster on the sixth Falcon 9 flight, and several subsequent F9 flights, to do a burn to reduce the rocket's horizontal velocity and then effect a second burn just before it reaches the water. SpaceX announced the test program in March 2013, and their intention to continue to conduct such tests until they can return to the launch site and perform a powered landing.[43]

Falcon 9 Flight 6's first stage performed the first propulsive-return over-water tests on 29 September 2013.[67] Although not a complete success, the stage was able to change direction and make a controlled entry into the atmosphere.[67] During the final landing burn, the ACS thrusters could not overcome an aerodynamically induced spin, and centrifugal force deprived the landing engine of fuel leading to early engine shutdown and a hard splashdown which destroyed the first stage. Pieces of wreckage were recovered for further study.[67] Elon Musk stated that Falcon 9 Flight 10, in 2014, will be the next attempt to recover a first stage.[68]

Launch sites

Launch Complex 40 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station was the Falcon 9's first launch site and is the main location for ISS launches and for payloads going to geostationary orbits. The second launch site is for polar-orbit launches and is located at Vandenberg Air Force Base's SLC-4, becoming active on 29 September 2013 when it launched the Canadian-built CASSIOPE satellite.[67][69] A third site, intended solely for commercial launches, is currently being planned, with locations in Texas, Florida, Georgia, or Puerto Rico being evaluated before a final decision is made.[70][71]

Launch prices

As of March 2013[update], Falcon 9 launch prices are $4,109 per kilogram ($1,864/lb) to low-Earth orbit when the launch vehicle is transporting its maximum cargo weight.[49]

Earlier, at an appearance in May 2004 before the U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, Elon Musk testified, "Long term plans call for development of a heavy lift product and even a super-heavy, if there is customer demand. [...] Ultimately, I believe $500 per pound ($1100/kg) [of payload delivered to orbit] or less is very achievable."[72]

SpaceX formally announced plans for the Falcon 9 on September 8, 2005, describing it as being a "fully reusable heavy lift launch vehicle."[73] A Falcon 9 medium[clarification needed] was described as being capable of launching approximately 21,000 lb (9,500 kg) to low Earth orbit, priced at $27 million per flight ($1286/lb).[74][citation needed]

According to SpaceX in May 2011, a standard Falcon 9 launch will cost $54 million ($1,862/lb), while NASA Dragon cargo missions to the ISS will have an average cost of $133 million.[75]

At a National Press Club luncheon on Thursday, September 29, 2011, Elon Musk stated that fuel and oxygen for the Falcon 9 v1.0 rocket total about $200,000 for the Falcon 9 rocket.[76] The first stage uses 39,000 US gallons (150,000 L; 32,000 imp gal) of liquid oxygen and almost 25,000 US gallons (95,000 L; 21,000 imp gal) of kerosene, while the second stage uses 7,300 US gallons (28,000 L; 6,100 imp gal) of liquid oxygen and 4,600 US gallons (17,000 L; 3,800 imp gal) of kerosene.[77]

Secondary payload services

Falcon 9 payload services include secondary and tertiary payload connection via an ESPA-ring, the same interstage adapter first utilized for launching secondary payloads on US DoD missions that utilize the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicles (EELV) Atlas V and Delta IV. This reduces launch costs[citation needed] for the primary mission and enables secondary and even tertiary missions with minimal impact to the original mission. As of 2011[update], SpaceX announced pricing for ESPA-compatible payloads on the Falcon 9.[78]

Launch history

As of September 2013, SpaceX has made six launches of the Falcon 9 since 2010, and all six have successfully delivered their primary payloads to Low Earth orbit.

The first Falcon 9 flight was launched, after several delays, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on June 4, 2010, at 2:45 pm EDT (19:45 UTC) with a successful orbital insertion.[20]

The second launch of the Falcon 9, and the first of the SpaceX Dragon spacecraft atop it, occurred at 10:43 EST (15:43 UTC) on December 8, 2010, from Cape Canaveral.[79] The Dragon spacecraft completed two orbits, then splashed down in the Pacific Ocean.[21] A second NASA-contracted demonstration flight was flown in 2012, followed by the first two ISS resupply flights in late 2012 and early 2013.

The Falcon 9 Flight 6 successfully flew on 29 September 2013, [67][80] and was the first launch of the substantially upgraded Falcon 9 v1.1 vehicle. The launch included a number of Falcon 9 "firsts":[4][81]

- First use of the upgraded Merlin 1D engines, generating approximately 56 percent more sea-level thrust than the Merlin 1C engines used on all previous Falcon 9 vehicles.

- First use of the significantly longer first stage, which holds the additional propellant for the more powerful engines.

- The nine Merlin 1D engines on the first stage are arranged in an octagonal pattern with eight engines in a circle and the ninth in the center.[41]

- First launch from SpaceX's new launch facility, Space Launch Complex 4, at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California, and will be the first launch over the Pacific ocean using the facilities of the Pacific test range.

- First Falcon 9 launch to carry a satellite payload for a commercial customer, and also the first non-CRS mission. Each prior Falcon 9 launch was of a Dragon capsule or a Dragon-shaped test article, although SpaceX has previously successfully launched and deployed a satellite on the Falcon 1, Flight 5 mission.

- First Falcon 9 launch to have a jettisonable payload fairing, which introduces the risk of an additional separation event.

While a number of the new capabilities were successfully tested on the flight, there was an issue with the second stage on 29 Sep 2013. SpaceX was unsuccessful in reigniting the second stage Merlin 1D vacuum engine once the rocket had deployed its primary payload (CASSIOPE) and all of its nanosat secondary payloads.[82] "A second burn of the upper stage will be required during SpaceX’s next mission, intended to place the SES-8 telecommunications satellite into geostationary transfer orbit for satellite operator SES of Luxembourg."[82]

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Capabilities & Services". SpaceX. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "Falcon 9". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Falcon 9". SpaceX. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ^ a b Graham, Will. "SpaceX successfully launches debut Falcon 9 v1.1". NASASpaceFlight. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ "Detailed Mission Data – Falcon-9 ELV First Flight Demonstration". Mission Set Database. NASA GSFC. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

- ^ "Falcon 9". SpaceX. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ "SpaceX Falcon 9 Upper Stage Engine Successfully Completes Full Mission Duration Firing" (Press release). SpaceX. March 10, 2009.

- ^ "SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket launch in California". CBS News. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ Mr. Alan Lindenmoyer, Manager, NASA Commercial Crew & Cargo Program, quoted in Minutes of the NAC Commercial Space Committee, April 26, 2010

- ^ "THE FACTS ABOUT SPACEX COSTS". spacex.com. May 4, 2011.

- ^ "Falcon 9 Launch Vehicle NAFCOM Cost Estimates" (PDF). nasa.gov. August 2011.

- ^ Space Act Agreement between NASA and Space Exploration Technologies, Inc., for Commercial Orbital Transportation Services Demonstration (pdf)

- ^ Coppinger, Rob (2008-02-27). "SpaceX Falcon 9 maiden flight delayed by six months to late Q1 2009". Flight Global.

- ^ "SpaceX Conducts First Multi-Engine Firing of Falcon 9 Rocket" (Press release). SpaceX. 18 January 2008.

- ^ "SpaceX successfully conducts full mission-length firing of its Falcon 9 launch vehicle" (Press release). SpaceX. November 23, 2008.

- ^ "SpaceX announces Falcon 9 assembly underway at the Cape". Orlando Sentinel. 11 Feb 2010.

- ^ "Updates". SpaceX. February 25, 2010. Retrieved 2010-06-04.

- ^ Kremer, Ken (March 13, 2010). "Successful Engine Test Firing for SpaceX Inaugural Falcon 9". Universe Today. Retrieved 2010-06-04.

- ^ Kaufman, Marc (June 4, 2010). "Falcon 9 rocket launch aborted". Washington Post. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ^ a b Staff writer (August 20, 2010). "SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket enjoys successful maiden flight". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-06-05.

- ^ a b "COTS Demo Flight 1 status". SpaceFlight Now.

- ^ Q & A with SpaceX CEO Elon Musk: Master of Private Space Dragons, space.com, 2010-12-08, accessed 2010-12-09. "now have Falcon 9 and Dragon in steady production at approximately one F9/Dragon every three months. The F9 production rate doubles to one every six weeks in 2012."

- ^ "Production at SpaceX". SpaceX. 2013-09-24. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

- ^ a b

Svitak, Amy (2013-11-24). "Musk: Falcon 9 Will Capture Market Share". Aviation Week. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

SpaceX is currently producing one vehicle per month, but that number is expected to increase to '18 per year in the next couple of quarters.' By the end of 2014, she says SpaceX will produce 24 launch vehicles per year.

- ^ a b c d e f Klotz, Irene (2013-09-06). "Musk Says SpaceX Being "Extremely Paranoid" as It Readies for Falcon 9's California Debut". Space News. Retrieved 2013-09-13.

- ^ "SpaceX's reusable rocket testbed takes first hop". 2012-09-24. Retrieved 2012-11-07.

- ^ a b c d e f "Falcon 9 Overview". SpaceX. 8 May 2010.

- ^ a b Svitak, Amy (2012-11-18). "Dragon's "Radiation-Tolerant" Design". Aviation Week. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- ^ Mission Status Center, June 2, 2010, 1905 GMT, SpaceflightNow, accessed 2010-06-02, Quotation: "The flanges will link the rocket with ground storage tanks containing liquid oxygen, kerosene fuel, helium, gaserous nitrogen and the first stage ignitor source called triethylaluminum-triethylborane, better known as TEA-TAB."

- ^ a b "Falcon 9 Launch Vehicle Payload User's Guide, 2009" (PDF). SpaceX. 2009. Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- ^ a b c

"Musk ambition: SpaceX aim for fully reusable Falcon 9". NASAspaceflight.com. 2009-01-12. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

With Falcon I's fourth launch, the first stage got cooked, so we're going to beef up the Thermal Protection System (TPS). By flight six we think it's highly likely we'll recover the first stage, and when we get it back we'll see what survived through re-entry, and what got fried, and carry on with the process. That's just to make the first stage reusable, it'll be even harder with the second stage – which has got to have a full heatshield, it'll have to have deorbit propulsion and communication.

- ^ a b c Simberg, Rand (2012-02-08). "Elon Musk on SpaceX's Reusable Rocket Plans". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ^ "Falcon 9's commercial promise to be tested in 2013". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d "SpaceX Capabilities and Services". webpage. SpaceX. 2013. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- ^ a b c d e f "Space Launch report, SpaceX Falcon Data Sheet". Retrieved 2011-07-29.

- ^ "The Annual Compendium of Commercial Space Transportation: 2012" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. February 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (2012-05-18). "Q&A with SpaceX founder and chief designer Elon Musk". SpaceFlightNow. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- ^ "SpaceX Test-fires Upgraded Falcon 9 Core for Three Minutes". Space News. Retrieved 2013-08-11.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (20 June 2013). "Reducing risk via ground testing is a recipe for SpaceX success". NASASpaceFlight (not affiliated with NASA). Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ^ "Falcon 9". SpaceX. Retrieved 2013-08-02.

- ^ a b

"Octaweb". SpaceX News. 2013-07-29. Retrieved 2013-07-30.

The Octaweb structure of the nine Merlin engines improves upon the former 3x3 engine arrangement. The Octaweb is a metal structure that supports eight engines surrounding a center engine at the base of the launch vehicle. This structure simplifies the design and assembly of the engine section, streamlining our manufacturing process.

- ^

"Landing Legs". SpaceX News. 2013-07-29. Retrieved 2013-07-30.

The Falcon 9 first stage carries landing legs which will deploy after stage separation and allow for the rocket's soft return to Earth. The four legs are made of state-of-the-art carbon fiber with aluminum honeycomb. Placed symmetrically around the base of the rocket, they stow along the side of the vehicle during liftoff and later extend outward and down for landing.

- ^ a b c d

Lindsey, Clark (2013-03-28). "SpaceX moving quickly towards fly-back first stage". NewSpace Watch. Retrieved 2013-03-29.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "nsw20130328" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c

Messier, Doug (2013-03-28). "Dragon Post-Mission Press Conference Notes". Parabolic Arc. Retrieved 2013-03-30.

Q. What is strategy on booster recover? Musk: Initial recovery test will be a water landing. First stage continue in ballistic arc and execute a velocity reduction burn before it enters atmosphere to lessen impact. Right before splashdown, will light up the engine again. Emphasizes that we don't expect success in the first several attempts. Hopefully next year with more experience and data, we should be able to return the first stage to the launch site and do a propulsion landing on land using legs. Q. Is there a flight identified for return to launch site of the booster? Musk: No. Will probably be the middle of next year.

- ^ a b Mangels, John (2013-05-25). "NASA's Plum Brook Station tests rocket fairing for SpaceX". Cleveland Plain Dealer. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

- ^ Abbott, Joseph (2013-05-08). "SpaceX's Grasshopper leaping to NM spaceport". Waco Tribune. Retrieved 2013-05-09.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (2013-06-20). "Reducing risk via ground testing is a recipe for SpaceX success". NASAspaceflight.com. Retrieved 2013-10-24.

- ^ "Falcon 9 Overview". SpaceX. 2010. Retrieved 4 Apr 2011.

- ^ a b Upgraded Spacex Falcon 9.1.1 will launch 25% more than the old Falcon 9 and bring the price down to $4109 per kilogram to LEO, NextBigFuture, 22 Mar 2013.

- ^ Space Exploration Technologies, Inc., Reliability brochure, v 12, undated (accessed Dec. 29, 2011)

- ^ "Russia scores success in its 1,700th Soyuz launch". Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ^ "SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket facts".

- ^ NASA PAO, Hold-Down Arms and Tail Service Masts, Moonport, SP-4204 (accessed 26 August 2010)

- ^ Behind the Scenes With the World's Most Ambitious Rocket Makers, Popular Mechanics, 2009-09-01, accessed 2012-12-11. "It is the first since the Saturn series from the Apollo program to incorporate engine-out capability—that is, one or more engines can fail and the rocket will still make it to orbit."

- ^

"Updates: December 2007". Updates Archive. SpaceX. Dec 2007. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

Once we have all nine engines and the stage working well as a system, we will extensively test the "engine out" capability. This includes explosive and fire testing of the barriers that separate the engines from each other and from the vehicle. ... It should be said that the failure modes we've seen to date on the test stand for the Merlin 1C are all relatively benign – the turbo pump, combustion chamber and nozzle do not rupture explosively even when subjected to extreme circumstances. We have seen the gas generator (which drives the turbo pump assembly) blow apart during a start sequence (there are now checks in place to prevent that from happening), but it is a small device, unlikely to cause major damage to its own engine, let alone the neighboring ones. Even so, as with engine nacelles on commercial jets, the fire/explosive barriers will assume that the entire chamber blows apart in the worst possible way. The bottom close out panels are designed to direct any force or flame downward, away from neighboring engines and the stage itself. ... we've found that the Falcon 9's ability to withstand one or even multiple engine failures, just as commercial airliners do, and still complete its mission is a compelling selling point with customers. Apart from the Space Shuttle and Soyuz, none of the existing [2007] launch vehicles can afford to lose even a single thrust chamber without causing loss of mission.

- ^ "Falcon 9 Overview". SpaceX. 8 May 2010.

- ^ a b

de Selding, Peter B. (2012-10-11). "Orbcomm Craft Launched by Falcon 9 Falls out of Orbit". Space News. Retrieved 2012-10-12.

Orbcomm requested that SpaceX carry one of their small satellites (weighing a few hundred pounds, vs. Dragon at over 12,000 pounds)... The higher the orbit, the more test data [Orbcomm] can gather, so they requested that we attempt to restart and raise altitude. NASA agreed to allow that, but only on condition that there be substantial propellant reserves, since the orbit would be close to the space station. It is important to appreciate that Orbcomm understood from the beginning that the orbit-raising maneuver was tentative. They accepted that there was a high risk of their satellite remaining at the Dragon insertion orbit. SpaceX would not have agreed to fly their satellite otherwise, since this was not part of the core mission and there was a known, material risk of no altitude raise.

- ^ Leitenberger, Bernd. "SpaceX CRS-1 Nachlese". Retrieved 2012-10-29.

- ^ a b Lindsey, Clark S. "Interview* with Elon Musk". HobbySpace. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- ^ Simburg, Rand. "SpaceX Press Conference". Retrieved 16 June 2010.. Musk quote: “We will never give up! Never! Reusability is one of the most important goals. If we become the biggest launch company in the world, making money hand over fist, but we’re still not reusable, I will consider us to have failed.”

- ^

"SpaceX chief details reusable rocket". Washington Post. 2011-09-30. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

Both of the rocket's stages would return to the launch site and touch down vertically, under rocket power, on landing gear after delivering a spacecraft to orbit.

Cite error: The named reference "wp20110929" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Wall, Mike (2011-09-30). "SpaceX Unveils Plan for World's First Fully Reusable Rocket". SPACE.com. Retrieved 2011-10-11. Cite error: The named reference "sdc20110930" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ http://www.spacex.com/assets/video/spacex-rtls-green.mp4

- ^ National Press Club: The Future of Human Spaceflight, cspan, 29 Sep 2011.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (2012-12-24). "SpaceX launches its Grasshopper rocket on 12-story-high hop in Texas". MSNBC Cosmic Log. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ^ First test of the Falcon 9-R (reusable) ignition system, 28 April 2013

- ^ a b c d e

Graham, William (2013-09-29). "SpaceX successfully launches debut Falcon 9 v1.1". NASAspaceflight.com. Archived from the original on 2013-09-29. Retrieved 2013-09-29.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Messier, Doug (2013-09-29). "Falcon 9 Launches Payloads into Orbit From Vandenberg". Parabolic Arc. Retrieved 2013-09-30.

- ^ "SpaceX Press Conference". Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ^ "Texas, Florida Battle for SpaceX Spaceport". Parabolic Arc. Retrieved 2012-11-06.

- ^

Dean, James (2013-05-07). "3 states vie for SpaceX's commercial rocket launches". USA Today. Archived from the original on 2013-09-29.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Testimony of Elon Musk (May 5, 2004). "Space Shuttle and the Future of Space Launch Vehicles". U.S. Senate.

- ^ "SpaceX Announces the Falcon 9 Fully Reusable Heavy Lift Launch Vehicle" (Press release). SpaceX. 2005-09-08.

- ^ David, Leonard. "SpaceX tackles reusable heavy launch vehicle". MSN. MSNBC.

- ^ http://www.spacex.com/usa.php

- ^ "National Press Club: The Future of Human Spaceflight" (Press release). c-span.org. 2012-01-14.

- ^ [1]

- ^

Foust, Jeff (2011-08-22). "New opportunities for smallsat launches". The Space Review. Retrieved 2011-09-27.

SpaceX ... developed prices for flying those secondary payloads ... A P-POD would cost between $200,000 and $325,000 for missions to LEO, or $350,000 to $575,000 for missions to geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO). An ESPA-class satellite weighing up to 180 kilograms would cost $4–5 million for LEO missions and $7–9 million for GTO missions, he said.

- ^ BBC News. "Private space capsule's maiden voyage ends with a splash." December 8, 2010. December 8, 2010. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-11948329

- ^ "Spaceflight Now - Worldwide launch schedule". Spaceflight Now Inc. 1 June 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (2013-03-27). "After Dragon, SpaceX's focus returns to Falcon". NewSpace Journal. Retrieved 2013-04-05.

- ^ a b Ferster, Warren (2013-09-29). "Upgraded Falcon 9 Rocket Successfully Debuts from Vandenberg". Space News. Retrieved 2013-09-30.

<references> tag (see the help page).External links

- Falcon 9 official page

- Falcon Heavy official page

- Test firing of two Merlin 1C engines connected to Falcon 9 first stage, Movie 1, Movie 2 (January 18, 2008)

- Press release announcing design (September 9, 2005)

- SpaceX hopes to supply ISS with new Falcon 9 heavy launcher (Flight International, September 13, 2005)

- SpaceX launches Falcon 9, With A Customer (Defense Industry Daily, September 15, 2005)