Shakespeare coat of arms

The Shakespeare coat of arms is an English coat of arms. It was granted to John Shakespeare (c. 1531 – 1601), a glover from Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, in 1596, and was used by his son, the playwright William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616), and other descendants.[1]

History

John Shakespeare made enquiries concerning a coat of arms around 1575.[2][3] Possibly he met the herald Robert Cooke of the College of Arms when Cooke visited Warwickshire. Cooke may have designed the "pattern" that was later granted.[4]: 27–28 John had been a bailiff and had the social standing and marriage that made such a request possible. Nothing came of it, presumably because of economic difficulties; such applications were expensive.[3][5][6]

In 1596, the application was renewed, either by John or by his son William on John's (and probably William's own) behalf. As the eldest son, William could make a request for his family to be granted a coat of arms. At the time, William had enough money, and could hope for support from influential men such as Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton and Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex.[3][2][7]

Two drafts of the grant document from 1596, written by the herald William Dethick, have been preserved.[3][2][7] The drafts have minor differences, and would have been used as a basis for the official grant or "letters patent", which as far as is known no longer exists,[8] though there is a late 17th-century copy.[9] According to the palaeographer Charles Hamilton, the drafts were written by William, and if so they are existing examples of his handwriting.[7] The heraldry scholar Wilfrid Scott-Giles suggests that the changes and additions that can be seen on the drafts may have been made during discussions between William and the heralds.[4]: 29

William's and his wife Anne's only son, the 11-year-old Hamnet, died and was buried only a few months before the application was approved. They now had no son to inherit the sought-after honour. William wrote in Macbeth, 10 years later:[10][11]

Upon my head they placed a fruitless crown

And put a barren sceptre in my grip,

Thence to be wrenched with an unlineal hand,

No son of mine succeeding.

A draft document from 1599 requests that the coat of arms of the Shakespeare family be combined, or impaled, with that of the Arden family, the higher-ranked family of John's wife Mary.[12] It is likely that she wanted the Arden family's coat of arms to descend to their children, but this only became possible after her husband's grant. It appears that the coat of arms of a more prestigious branch of the Arden family was requested, but stricken from the draft.[4]: 28, 32–33

According to the Shakespeare scholar James S. Shapiro, the 1599 document includes embellishments and outright fabrications.[10] The clergyman William Harrison wrote in 1577 that the heralds "do of custom pretend antiquity and service, and many gay things thereunto".[4]: 30 [13] For unknown reasons, the Shakespeares did not use the combined version, which would have been considered of higher status.[12] Possibly it was never granted. Scott-Giles hypothesises that William simply found the un-combined version more aesthetically pleasing.[4]: 32–33

In 1602, Ralph Brooke, a rival of Dethick, challenged a number of coats of arms approved by Dethick, including Shakespeare's. According to Brooke, the Shakespeares did not qualify, and the coat of arms was too similar to an existing coat of arms. Dethick argued that there was sufficient distinction, and noted John Shakespeare's qualifications. The dispute seems to have been resolved in Dethick's favour.[14][3][15]

The coat of arms can be seen on the seal of William's daughter Susanna Hall,[15] and can partly be seen on the wax seal of the will of her daughter Elizabeth Barnard, the playwright's last surviving descendant.[2][16]

Description

The 1596 drafts of the grant document define the coat of arms this way:

Gold, on a bend sable [black diagonal bar], a spear of the first [gold, the first colour mentioned], steeled argent [with a silver head]; and for his crest... a falcon his wings displayed argent [silver], standing on a wreath of his colours supporting a spear gold, steeled as aforesaid, set upon a helmet with mantles and tassles.[1]

Added is a simple sketch and what is presumed to be a motto, Non Sanz Droict, old French for "Not without right". There is no indication that the motto was ever used by the Shakespeares,[1][3] though it has been taken for a motto by the Warwickshire County Council.[4]: 41 In what may have been a joke on the part of the writer, the motto was first written Non, Sanz Droict, "No, without right". This was stricken and corrected.[17][4]: 31–32

Symbolism

The spear is an allusion to the family name and the falcon, with "shaking" wings, could refer to an interest in hunting.[15][18] Shakespeare scholar Katherine Duncan-Jones connects the falcon to the coat of arms of Henry Wriothesley, which displays 4 silver falcons or hawks.[19][20] However, the Shakespeare design may have been made when William was a boy, and if so, there is no such connection.[4]: 31

She proposes that the colours on the shield imply that the Shakespeare family had included crusading knights. The spear, or lance, can be seen as resembling a silver-tipped golden pen.[19][11][21]

Scott-Giles states that apart from the connection between the spear and the family name, the design has no obvious other meaning.[4]: 31

Similar coats of arms

Similar coats of arms have been granted to people named Shakespeare in 1858, 1918, and in 1946, when the Shakespeare Baronetcy was created.[4]: 41

In fiction

A speech in the play Richard II, written around 1595, mentions a lance and a falcon, possibly inspired by William's dealings with the heralds.[4]: 35 The falcon is the type of bird most often mentioned in his plays.[21]

It has been suggested that William's friend Ben Jonson alluded to the coat of arms in the 1599 comedy Every Man out of His Humour. In this play, the rustic Sogliardo, who has just purchased a coat of arms, is told to take the motto Not without mustard.[22][3][4]: 32

The character Claudius Marcus wears the coat of arms in the 1968 Star Trek episode "Bread and Circuses".[23][24]

In the 2016 British sitcom Upstart Crow John's desire and William's application for a coat of arms is a recurring plot point. It is granted in the episode "Wild Laughter in the Throat of Death".[25][26]

Gallery

-

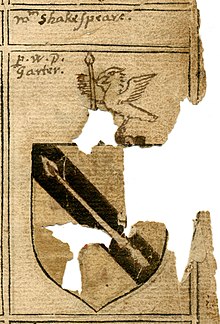

Sketch from draft document, 1596.

-

Coat of arms of John Hall, William Shakespeare's son-in-law, combined with the Shakespeare coat of arms.

-

Late 17th-century version.[27]

-

Version from 1787, Arden family combination below

-

The Gail Kern Paster Reading Room at the Folger Shakespeare Library, with bookshelves decorated with the coat of arms

-

Shakespeare's Birthplace, with coat of arms displayed.

See also

- Shakespeare's signet ring, a seal ring that may have belonged to William Shakespeare

- Heather Wolfe, Shakespeare coat of arms scholar

References

- ^ a b c "Shakespeare Coat of Arms". Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d Schuessler, Jennifer (29 June 2016). "Shakespeare: Actor. Playwright. Social Climber". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Schoenbaum, S. (1987). William Shakespeare: a compact documentary life (Rev. with a new postscript ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 38, 227-232. ISBN 0195051610.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Scott-Giles, C. Wilfrid (Charles Wilfrid) (1950). Shakespeare's heraldry. London, Dent.

- ^ Kay, Dennis (1995). William Shakespeare: his life and times. New York: Twayne Publishers. p. 8. ISBN 9780805770636.

- ^ Wilson, Ian (1994). Shakespeare, the evidence: unlocking the mysteries of the man and his work. St. Martin's Press. p. 37, 270. ISBN 9780312113353.

- ^ a b c Hamilton, Charles (1985). In search of Shakespeare: a reconnaissance into the poet's life and handwriting (First ed.). San Diego. pp. 127–129. ISBN 0151445346.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Wolfe, Heather (20 January 2016). "Grant of arms to John Shakespeare: draft 1". Shakespeare documented. Folger Shakespeare Library. doi:10.37078/117. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Wolfe, Heather. "Grant of arms to various families from 33 Elizabeth to 8 Car I inclusive chiefly by Sir William Dethick Garter King of Arms". Shakespeare Documented. Folger Shakespeare Library. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ a b Shakespeare the Man: New Decipherings. Rowman & Littlefield. 13 March 2014. pp. 26, 40–41. ISBN 978-1-61147-676-7.

- ^ a b Beer, Anna (26 April 2021). The Life of the Author: William Shakespeare. John Wiley & Sons. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-119-60527-0.

- ^ a b "Draft confirmation of arms, impaling Arden on Shakespeare, 1599". Shakespeare Documented. Folger Shakespeare Library. 1599. doi:10.37078/119.

- ^ Harrison, William (1577). "Chapter I, Of Degrees of People in the Commonwealth of Elizabethan England". A Description of Elizabethan England.

- ^ "Shakespeare's arms defended: College of Arms copy of Garter and Clarenceux's reply". Shakespeare documented. Folger Shakespeare Library. 20 January 2016. doi:10.37078/120.

- ^ a b c The Oxford companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press. 2001. p. 21-22. ISBN 0-19-811735-3.

- ^ "Will of Elizabeth Barnard, Shakespeare's granddaughter and his last surviving descendant: original copy". Shakespeare Documented. Folger Shakespeare Library. doi:10.37078/543.

- ^ Ramsay, Nigel (1 July 2014). "William Dethick and the Shakespeare Grants of Arms". The Collation. Folger Shakespeare Library. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Wells, Stanley (2003). Shakespeare: for all time. Oxford [U.K.]: Oxford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 0195160932.

- ^ a b Duncan-Jones, Katherine (2 March 2018). "Shakespeare part 2. Shakespeare among the Heralds". Coat of Arms. Winter 2000 (192). Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Kaaber, Lars (20 June 2017). Hamlet's Age and the Earl of Southampton. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-4438-9613-9.

- ^ a b Dingfelder, Sadie (10 July 2014). "A draft of Shakespeare's coat of arms is on display for Folger Shakespeare Library's 'Symbols of Honor'". Washington Post. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ Tiffany, Grace (13 March 2014). Shakespeare the Man: New Decipherings. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-61147-676-7.

- ^ Tichenor, Austin (27 August 2019). "Shakespeare in Star Trek: quotes, plot lines, and more references". Shakespeare & Beyond. Folger Shakespeare Library. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Kosowan, Gene (12 August 2020). "10 Shakespeare References In The Star Trek Franchise That You Probably Missed". Screen Rant. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Stubbs, David (11 September 2017). "Monday's best TV: The Search for a New Earth, Upstart Crow, Rellik". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "Upstart Crow Series 3, Episode 2 – Wild Laughter In The Throat Of Death". British Comedy Guide. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "John Shakespeare's grant of arms". Shakespeare Documented. Folger Shakespeare Library. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

External links

- Shakespeare's coat of arms, all documents, at Shakespeare Documented

- Shakespeare part 1. The Grants of Arms to Shakespeare's Father, 1964 article at The Heraldry Society

- Shakespeare part 2. Shakespeare among the Heralds, 2000 article by Katherine Duncan-Jones at The Heraldry Society

- Dr Kat and the Arms of Shakespeare, video at Reading the Past

- Heraldry, Will applies for a coat of arms on Upstart Crow

![Late 17th-century version.[27]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ad/John_Shakespeare_coat_of_arms.jpg/72px-John_Shakespeare_coat_of_arms.jpg)