Senusret II

| Senusret II | |

|---|---|

| Senwosret II, Sesostris II | |

Head of a statue of Senusret II from Karnak | |

| Pharaoh | |

| Reign | Co-regent of five years; sole reign of around fifteen years.[1][note 1] |

| Predecessor | Amenemhat II |

| Successor | Senusret III |

| Consort | Khenemetneferhedjet I, Nofret II, Itaweret (?), Khenmet (?) |

| Children | Senusret III, Senusret-sonbe, Itakayt, Neferet, Sithathoryunet |

| Father | Amenemhat II |

| Burial | Pyramid of Senusret II |

| Dynasty | Twelfth Dynasty |

Senusret II was the fourth pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled from 1897 BC to 1878 BC. His pyramid was constructed at El-Lahun. Senusret II took a great deal of interest in the Faiyum oasis region and began work on an extensive irrigation system from Bahr Yussef through to Lake Moeris through the construction of a dike at El-Lahun and the addition of a network of drainage canals. The purpose of his project was to increase the amount of cultivable land in that area.[11] The importance of this project is emphasized by Senusret II's decision to move the royal necropolis from Dahshur to El-Lahun where he built his pyramid. This location would remain the political capital for the 12th and 13th Dynasties of Egypt. Senusret II was known by his prenomen Khakheperre, which means "The Ka of Re comes into being". The king also established the first known workers' quarter in the nearby town of Senusrethotep (Kahun).[12]

Unlike his successor, Senusret II maintained good relations with the various nomarchs or provincial governors of Egypt who were almost as wealthy as the pharaoh.[13] His Year 6 is attested in a wall painting from the tomb of a local nomarch named Khnumhotep II at Beni Hasan.

Reign

Co-regency

Co-regencies are a major issue for Egyptologists' understanding of the history of the Middle Kingdom and the Twelfth Dynasty.[14][15] The Egyptologist Claude Obsomer wholly rejects the possibility of co-regencies in the Twelfth Dynasty.[16] The Egyptologist Karl Jansen-Winkeln[17] having investigated Obsomer's work concluded in favour of co-regencies.[18] Jansen-Winkeln cites a rock stele found at Konosso as irrefutable evidence in favour of a co-regency between Senusret II and Amenemhat II, and by extension proof of co-regencies in the Twelfth Dynasty.[19] The Egyptologist William J. Murnane states that "the co-regencies of the period are all known ... from double-dated[note 2] documents".[21] The Egyptologist Thomas Schneider concludes that recently discovered documents and archaeological evidence are effectively proof of co-regencies in this period.[22]

Some sources ascribe a co-regency period to Senusret II's rule, with his father Amenemhat II as his co-regent. The Egyptologist Peter Clayton ascribes at least three years of co-regency to Senusret II's reign.[23] The Egyptologist Nicolas Grimal assigns nearly five years of co-regency prior to sole accession to the throne.[1]

Length of reign

The lengths of the reigns of Senusret II and Senusret III are one of the main considerations for discerning the chronology of the Twelfth Dynasty.[15] The Turin Canon is believed to assign a reign of 19 years to Senusret II and 30 years of reign to Senusret III.[25] This traditional view was challenged in 1972 when the Egyptologist William Kelly Simpson observed that the latest attested regnal year for Senusret II was his 7th, and similarly for Senusret III his 19th.[25]

Kim Ryholt, a professor of Egyptology at the University of Copenhagen, suggests the possibility that the names on the canon had been misarranged and offers two possible regnal lengths for Senusret II: 10+ years, or 19 years.[26] Several Egyptologists, such as Thomas Schneider, cite Mark C. Stone's 1997 article in the Göttinger Miszellen as determining that Senusret II's highest recorded regnal year was his 8th, based on Stela Cairo JE 59485.[27]

Some scholars prefer to ascribe him a reign of only 10 years and assign the 19-year reign to Senusret III instead. Other Egyptologists, however, such as Jürgen von Beckerath and Frank Yurco, have maintained the traditional view of a longer 19-year reign for Senusret II given the level of activity undertaken by the king during his reign.[citation needed] Yurco notes that reducing Senusret II's regnal length to 6 years poses difficulties because:

That pharaoh built a complete pyramid at Kahun, with a solid granite funerary temple and complex of buildings. Such projects optimally took fifteen to twenty years to complete, even with the mudbrick cores used in Middle Kingdom pyramids.[28]

At present, the problem concerning the reign length of Senusret II is irresolvable but many Egyptologists today prefer to assign him a reign of 9 or 10 years only given the absence of higher dates attested for him beyond his 8th regnal year. This would entail amending the 19-year figure which the Turin Canon assigns for a 12th dynasty ruler in his position to 9 years instead. However, Senusret II's monthly figure on the throne might be ascertained. According to Jürgen von Beckerath, the temple documents of El-Lahun, the pyramid city of Sesostris/Senusret II often mention the Festival of "Going Forth to Heaven" which might be the date of death for this ruler.[29] These documents state that this Festival occurred on IV Peret day 14.[30][31][32] However, Rita Gautschy states that this Festival date did not mark the actual day of Senusret II's death, but of his funeral or burial.[33] Lisa Saladino Haney observe. based on Gautschy's interpretation of this date, "Therefore, if one takes seventy days from the feast day IV Peret 14, one gets II Peret 4 as the approximate date of death of Senwosret/[Senusret II].[34]

Domestic activities

The Faiyum Oasis, a region in Middle Egypt, has been inhabited by humans for more than 8000 years.[35] It became an important centre in Egypt during the Middle Kingdom.[35] Throughout the period, rulers undertook developmental projects turning Faiyum into an agricultural, religious, and resort-like centre.[35] The oasis was located 80 km (50 mi) south-west of Memphis offering arable land[1] centred around Lake Moeris, a natural body of water.[35]

Senusret II initiated a project to exploit the marshy region's natural resources for hunting and fishing, a project continued by his successors and which "matured" during the reign of his grandson Amenemhat III.[1] To set off this project, Senusret II developed an irrigation system with a dyke and a network of canals which siphoned water from Lake Moeris.[9][1] The land reclaimed in this project was then farmed.[36]

Cults honouring the crocodile god Sobek were prominent at the time.[35]

Activities outside Egypt

Senusret II's reign ushered in a period of peace and prosperity, with no recorded military campaigns and the proliferation of trade between Egypt and the Near-East.[9]

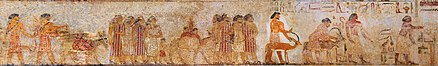

Around the same time, parties of Western Asiatic foreigners visiting the Pharaoh with gifts are recorded, as in the tomb paintings of 12th-dynasty official Khnumhotep II, who also served under Senusret III. These foreigners, possibly Canaanites or Bedouins, are labelled as Aamu (ꜥꜣmw), including the leading man with a Nubian ibex labelled as Abisha the Hyksos (𓋾𓈎𓈉 ḥḳꜣ-ḫꜣsw, Heqa-kasut for "Hyksos"), the first known instance of the name "Hyksos".[37][38][39][40]

Succession

There is an absence of serious evidence for a co-regency between Senusret II and Senusret III.[41] Murnane identifies that the only existing evidence for a coregency of Senusret II and III is a scarab with both kings names inscribed on it.[42] The association can be explained as being the result of retroactive dating where Senusret II's final regnal year was absorbed into Senusret III's first one, as would be supported by contemporaneous evidence from the Turin Canon which give Senusret II a regnal duration of 19 full regnal years and a partial one.[43] A dedicatory inscription celebrating the resumption of rituals begun by Senusret II and III, and a papyrus with entries identifying Senusret II's nineteenth regnal year and Senusret III's first regnal year are scant evidence and do not necessitate a coregency.[42] Murnane argues that if there was a coregency, it could not have lasted more than a few months.[42]

The evidence from the papyrus document is now obviated by the fact that the document has been securely dated to Year 19 of Senusret III and Year 1 of Amenemhet III.[citation needed] At present, no document from Senusret II's reign has been discovered from Lahun, the king's new capital city.

Tomb treasure

In 1889, the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie found "a marvellous gold and inlaid royal uraeus" that must have originally formed part of Senusret II's looted burial equipment in a flooded chamber of the king's pyramid tomb.[44] It is now located in the Cairo Museum. The tomb of Princess Sithathoriunet, a daughter of Senusret II, was also discovered by Egyptologists in a separate burial site. Several pieces of jewellery from her tomb including a pair of pectorals and a crown or diadem were found there. They are now displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of New York or the Cairo Museum in Egypt.

In 2009, Egyptian archaeologists announced the results of new excavations led by the Egyptologist Abdul Rahman Al-Ayedi. They described unearthing a cache of pharaonic-era mummies in brightly painted wooden coffins near the Lahun pyramid. The mummies were reportedly the first to be found in the sand-covered desert rock surrounding the pyramid.[45]

Pyramid

The pyramid was built around a framework of limestone radial arms, similar to the framework used by Senusret I. Instead of using an infill of stones, mud and mortar, Senusret II used an infill of mud bricks before cladding the structure with a layer of limestone veneer. The outer cladding stones were locked together using dovetail inserts, some of which still remain. A trench was dug around the central core that was filled with stones to act as a French Drain. The limestone cladding stood in this drain, indicating that Senusret II was concerned with water damage.

There were eight mastabas and one small pyramid to the north of Senusret's complex and all were within the enclosure wall. The wall had been encased in limestone that was decorated with niches, perhaps as a copy of Djoser's complex at Saqqara. The mastabas were solid and no chambers have found within or beneath, indicating that they were cenotaphs and possibly symbolic in nature. Flinders Petrie investigated the auxiliary pyramid and found no chambers.[citation needed]

The entrances to the underground chambers were on the southern side of the pyramid, which confused Flinders Petrie for some months as he looked for the entrance on the traditional northern side.

The builders' vertical access shaft had been filled in after construction and the chamber made to look like a burial chamber. This was no doubt an attempt to convince tomb robbers to look no further.

A secondary access shaft led to a vaulted chamber and a deep well shaft. This may have been an aspect of the cult of Osiris, although it may have been to find the water table. A passage led northwards, past another lateral chamber and turned westwards. This led to an antechamber and vaulted burial chamber, with a sidechamber to the south. The burial chamber was encircled by a unique series of passages that may have reference to the birth of Osiris. A large sarcophagus was found within the burial chamber; it is larger than the doorway and the tunnels, showing that it was put in position when the chamber was being constructed and it was open to the sky. The limestone outer cladding of the pyramid was removed by Rameses II so he could re-use the stone for his own use. He left inscriptions that he had done so.

See also

Notes

- ^ Proposed dates for Senusret II's reign: c. 1900–1880 BCE,[2] c. 1897–1878 BCE,[3][4][5] c. 1897–1877 BCE,[6] c. 1895–1878 BCE,[7] c. 1877–1870 BCE.[8][9]

- ^ A document with regnal dates for two kings. One such double-date is found on the stela from Konosso cited by Jansen-Winkeln,[19] which identifies Senusret II's third regnal year first, and Amenemhat II's thirty-fifth regnal year after it.[20]

References

- ^ a b c d e Grimal 1992, p. 166.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 289.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Arnold 2003, p. 267.

- ^ a b c Clayton 1994, p. 78.

- ^ Frey 2001, p. 150.

- ^ Grimal 1992, p. 391.

- ^ Shaw 2004, p. 483.

- ^ a b c Callender 2004, p. 152.

- ^ a b c d e f Leprohon 2013, p. 59.

- ^ Verner 2002, p. 386.

- ^ Petrie 1891, p. 5ff.

- ^ Clayton 1994, p. 83.

- ^ Callender 2004, pp. 137–138.

- ^ a b Simpson 2001, p. 453.

- ^ Schneider 2006, p. 170.

- ^ Jansen-Winkeln 1997, pp. 115–135.

- ^ Schneider 2006, pp. 170–171.

- ^ a b Jansen-Winkeln 1997, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Schneider 2006, p. 172.

- ^ Murnane 1977, p. 7.

- ^ Schneider 2006, p. 171.

- ^ Clayton 1994, p. 82.

- ^ "Guardian Figure". www.metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^ a b Ryholt 1997, p. 14.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Schneider 2006, p. 172 citing Stone (1997, pp. 91–100).

- ^ Yurco 2014, p. 69 citing Edwards (1985, pp. 98 & 292) and Grimal (1992, pp. 166 & 391).

- ^ von Beckerath 1995, p. 447.

- ^ Borchardt 1899, p. 91.

- ^ Gardiner 1945, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Simpson n.d., LA V900.

- ^ Rita Gautschy, "Monddaten aus dem Archiv von Illahun: Chronologie des Mittleren Reiches." ZÄS 138 (2011), p.17

- ^ Haney, Lisa Saladino. Visualizing Coregency: An Exploration of the Link between Royal Image and Co-Rule during the Reign of Senwosret III and Amenemhet III. Brill: Leiden/Boston, 2020, p.55

- ^ a b c d e Wilfong 2001, p. 496.

- ^ Callender 2004, pp. 152–153.

- ^ a b Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 131.

- ^ a b Bard 2015, p. 188.

- ^ a b Kamrin 2009, p. 25.

- ^ a b Curry, Andrew (2018). "The Rulers of Foreign Lands - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org.

- ^ Jansen-Winkeln 1997, p. 119.

- ^ a b c Murnane 1977, p. 9.

- ^ Murnane 1977, p. 228.

- ^ Clayton 1994, p. 80.

- ^ See El-Lahun recent discoveries and online Cache of mummies unearthed at Egypt's Lahun pyramid.

Sources

- Arnold, Dieter (2003). The Encyclopaedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture. London: I.B Tauris & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-1-86064-465-8.

- Bard, Kathryn A. (2015). An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9780470673362.

- Borchardt, Ludwig (1899). Erman, A.; Steindorff, G. (eds.). "Der zweite Papyrusfund von Kahun und die zeitliche Festlegung des mittleren Reiches der ägyptische Geschichte". Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde (in German) (37). Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung: 89–103. ISSN 2196-713X.

- Callender, Gae (2004). "The Middle Kingdom Renaissance (c.2055–1650 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 137–171. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Clayton, Peter (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-05074-3.

- de Morgan, Jacques; Bouriant, Urbain; Legrain, Georges Albert; Jéquier, Gustave; Barsanti, Alfred (1894). Catalogue des monuments et inscriptions de l'Ègypte (in French). Vienne: Adolphe Holzhausen. OCLC 741162031.

- Delia, Robert D. (1997). "Sésostris Ier; Étude chronologique et historique de règne. Étude No. 5 by Claude Obsomer". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt (in French): 267–268. doi:10.2307/40000813. ISSN 0065-9991. JSTOR 40000813.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05128-3.

- Edwards, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen (1985). The Pyramids of Egypt. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-140-22549-5.

- Frey, Rosa A. (2001). "Illahun". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Gardiner, Alan H. (1945). "Regnal Years and Civil Calendar in Pharaonic Egypt". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 31 (1): 11–28. doi:10.2307/3855380. ISSN 0307-5133. JSTOR 3855380.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Ian Shaw. Oxford: Blackwell publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8.

- Jansen-Winkeln, Karl (1997). "Zu den Koregenz der 12. Dynastie" (PDF). Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur (in German) (24): 115–135. ISSN 0340-2215.

- Kamrin, Janice (2009). "The Aamu of Shu in the Tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hassan". Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. 1: 22–36. S2CID 199601200.

- Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (2013). The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary. Vol. 33 of Writings from the ancient world. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-589-83736-2.

- Murnane, William J. (1977). "Ancient Egyptian Coregencies". Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization (SAOC) (40). Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. ISBN 978-0-918986-03-0. ISSN 0081-7554.

- Petrie, W. M. F. (1891). Illahun, Kahun and Gurob. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ryholt, Kim Steven Bardrum (1997). The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c. 1800–1550 B.C. CNI publications, 20. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press: University of Copenhagen. ISBN 978-87-7289-421-8.

- Schneider, Thomas (2006). "The relative chronology of the Middle Kingdom and the Hyksos Period (Dyns. 12–17)". In Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David A. (eds.). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Leiden, Boston: Brill. pp. 168–196. ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5.

- Shaw, Ian, ed. (2004). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Simpson, W. K. (n.d.). LA V900.

- Simpson, William Kelly (2001). "Twelfth Dynasty". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 453–457. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Stone, Mark (1997). "Reading the Highest Attested Date for Senwosret II: Stela Cairo JE 59485". Göttinger Miszellen (159): 91–100. ISSN 0344-385X.

- Van de Mieroop, Marc (2011). A History of Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405160704.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001e). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1703-8.

- Verner, Miroslav (2002). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture, and Science of Egypt's Great Monument. New York: Grove Press.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1995). "Nochmals zur Chronologie der XII. Dynastie". Orientalia (in German). 64 (4). Gregorian Biblical Press: 445–449. ISSN 0030-5367.

- Wilfong (2001). "Faiyum". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 496–497. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Yurco, Frank (2014). "Black Athena: An Egyptological Review". In Lefkowitz, Mary; Rogers, Guy Maclean (eds.). Black Athena Revisited. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 62–100. ISBN 978-0-8078-4555-4.

Further reading

- W. Grajetzki, The Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt: History, Archaeology and Society, Duckworth, London 2006 ISBN 0-7156-3435-6, 48-51