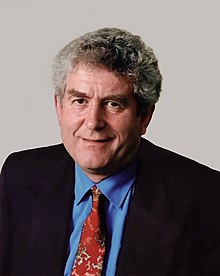

Rhodri Morgan

Rhodri Morgan | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 2007 | |

| First Minister of Wales[a] | |

| In office 15 February 2000 – 10 December 2009 Acting: 9 February 2000 – 15 February 2000 | |

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Deputy | Michael German Jenny Randerson (Acting) Ieuan Wyn Jones |

| Preceded by | Alun Michael |

| Succeeded by | Carwyn Jones |

| Leader of Welsh Labour | |

| In office 9 February 2000 – 1 December 2009 | |

| UK party leader | Tony Blair Gordon Brown |

| Preceded by | Alun Michael |

| Succeeded by | Carwyn Jones |

| Member of the Welsh Assembly for Cardiff West | |

| In office 6 May 1999 – 5 May 2011 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Mark Drakeford |

| Member of Parliament for Cardiff West | |

| In office 11 June 1987 – 14 May 2001 | |

| Preceded by | Stefan Terlezki |

| Succeeded by | Kevin Brennan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hywel Rhodri Morgan 29 September 1939 Roath, Cardiff, Wales |

| Died | 17 May 2017 (aged 77) Wenvoe, Wales |

| Political party | Welsh Labour |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent(s) | T. J. Morgan Huana Rees |

| Relatives | Prys Morgan (brother) Garel Rhys (second cousin) |

| Alma mater | St John's College, Oxford Harvard University |

| Cabinet | |

| Signature |  |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Leader of Welsh Labour (2000–2009)

First Minister of Wales (2000–2009)

|

||

Hywel Rhodri Morgan (29 September 1939 – 17 May 2017) was a Welsh Labour politician who was the First Minister of Wales and the Leader of Welsh Labour from 2000 to 2009. He was also the Assembly Member for Cardiff West from 1999 to 2011 and the Member of Parliament for Cardiff West from 1987 to 2001. He remains the longest-serving First Minister of Wales, having served in the position for 9 years and 304 days. He was Chancellor of Swansea University from 2011 until his death in 2017.

Early life and education

Hywel Rhodri Morgan was born at Mrs Gill's Nursing Home in Roath,[b] Cardiff on 29 September 1936.[4] He was the youngest of two children born to the Welsh writer and academic Thomas John (T.J.) Morgan and his wife Huana Morgan (née Rees), a writer and schoolteacher.[5][6] Morgan was born into a Welsh-speaking academic family.[7][8] His native language was Welsh, though he later became fluent in English, French and German as well.[4] His mother was one of the first women to study at University College, Swansea (now Swansea University), where she read Welsh.[9][7] She became a schoolteacher in Rhymney before settling in Radyr after her retirement.[9] Morgan's father also read Welsh at University College, Swansea, before reading Old Irish at University College, Dublin (UCD).[5] He became a Welsh language lecturer at the University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire (now Cardiff University) and a Welsh language professor at University College, Swansea,[4] where he also served as the vice-principal.[7] He met Huana at the National Eisteddfod of Wales in 1926 and they married in 1935.[10][5] Their first child, Morgan's brother Prys Morgan, was born in Cardiff in 1937.[11] He would grow up to become a history professor at Swansea University.[4] Morgan was also related to the academic Garel Rhys, who was his second cousin.[1]

Childhood and education

Morgan was raised with his brother Prys in the village of Radyr in outer Cardiff.[12][13] Until the age of 21, he lived with his family at 32 Heol Isaf,[4][1] in a house which sat on the main road of the village beside what is now a Methodist church.[14][1] Morgan was born in the first month of World War II, and the conflict had a great presence in his life during his early childhood.[1][3]: 1 He retained vivid memories of air raid sirens and prisoners of war into adulthood.[15] He also had a lifelong love for gardening which began when he watched his father grow vegetables for the wartime dig for victory campaign.[16][17] Radyr did, however, avoid the conflict's worst hardships.[18] Morgan had a mostly positive childhood, however he was often ill as an infant, and he almost died from pneumonia in 1942.[18][3]: 9 As a child, Morgan was nicknamed "fuzzy" by his family and friends for his curly, frizzy hair.[19]

In 1944, Morgan started attending Radyr Primary School. Having begun his education near the end of World War II, Morgan found his class in the first year of primary school was mostly populated by evacuees.[20][1] In 2005, Morgan remarked that the school was "like the League of Nations" because of the refugees and evacuees in Radyr.[15] The school was populated by a combination of evacuees and children from Radyr and Morganstown, another village in Cardiff,[20] with the children from Morganstown accounting for 66% of its population.[1] At the time, other children from Radyr would instead be sent to The Cathedral School in Llandaff, which was a private school.[18] Morgan showed signs of intelligence at school, and he would be tracked two academic years ahead of his peers, sharing classes with his older brother Prys.[18] He finished primary school in 1950 and passed his eleven-plus examination.[1][21] He attended Whitchurch Grammar School, becoming one of the few children from Radyr to attend a school in Whitchurch at the time.[22] At the grammar school, Morgan achieved high results in most subjects but science.[21] He finished his secondary education there in 1957[23] after winning a place at St John's College, Oxford on an open exhibition for the study of modern languages.[18]

At Oxford, Morgan studied modern languages for two academic terms before becoming disinterested in the subject and changing his subject to philosophy, politics and economics (PPE).[18][4] Morgan disliked the formal and ostentatious atmosphere of Oxford, and he later said he "had more respect for a semi-retired porter … than for the college president".[18][3]: 37 Morgan graduated from Oxford in 1961. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree with second class honours in PPE.[21][4] Morgan's American friends from his time at Oxford convinced him to apply for a place at Harvard University.[24] His second class honours was enough to secure him a place at Harvard to read a Master of Arts degree in government.[18][4] Morgan's studies in the United States were paid for through a scholarship.[25] He graduated from the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences with a Master of Arts degree in government in 1963,[26] before coming back to the United Kingdom in that year's summer.[18]

Early political involvement

Morgan's interest in politics began when he was eleven or twelve years old.[27][24] He had convinced his mother to take him to a local political meeting. At the meeting he saw Dorothy Rees, the Labour Party Member of Parliament (MP) for Barry, shouted down by public school pupils who supported the Conservative Party, which made her cry.[21][24] Morgan later recalled thinking: "I'm going to nail those bastards".[7][21] He was an active member of the Oxford University Labour Club[28] and is said to have discouraged other students at Oxford from joining Plaid Cymru.[29]: 2 By the time Morgan finished his studies at Harvard, he had decided to pursue his political interests practically rather than academically.[4] He joined the Labour Party in December 1963, where he became a member of the constituency Labour Party for Cardiff South East.[4][29]: 2

Early career

Morgan returned to the United Kingdom in the summer of 1963, where he took up his first job as a tutor organiser for the Workers' Educational Association (WEA),[18][10] which was then a training ground for future Labour Party MPs.[4] He was responsible for organising the association's tutors in South Wales.[28] In December, Morgan attended a local Labour Party meeting where he met Labour activists Julie Edwards and Neil Kinnock, the future leader of the Labour Party.[30][4][7] In the same month, Morgan moved into a flat in Cardiff, which he shared with Kinnock and two other local Labour Party activists until 1965.[31][4][7] Together, the flatmates engaged in anti-apartheid activism.[31][32] In the 1964 general election, Morgan campaigned with Edwards, Kinnock and Kinnock's partner Glenys in support of James Callaghan, the Labour MP for Cardiff South East who later became prime minister.[8][30] Morgan pursued a relationship with Edwards and after three years of campaigning together they married on 22 April 1967.[18] They had their first child, Mari, in 1968, and a second child, Siani, in 1969.[21] They also had an adopted son, Stuart, who was born in 1969 or 1970.[33] In 1966, Morgan was considered for selection as the Labour Party's prospective parliamentary candidate for Cardiff North, though he was ultimately not selected.[4] At the time, Morgan did not have a strong interest in a parliamentary career,[4] and whilst Kinnock and other former WEA workers quickly became MPs, he instead wanted to spend time with his family.[18] By the time of the 1970 general election he had a wife and three children, and he may have believed that a parliamentary career and its instabilities would take too much time away from them.[4] He left the WEA in 1965, taking up jobs as a research officer for Cardiff City Council, the Welsh Office and the Department of the Environment in that order,[28] remaining in this field of work until 1971.[18] At the Welsh Office, Morgan authored documents to expand the M4 motorway through parts of South Wales.[34] He also contributed to the creation of the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Centre in Wales, as well as the relocation of the Royal Mint and a part of the Inland Revenue to Wales.[35] In addition to his work as a research officer at Cardiff City Council, Morgan was also a junior town planner.[4][2]: 55 He reported to the Cardiff City Planning Department.[26] In 1972, Morgan became a civil servant at the Department of Trade and Industry[36] where he worked for Christopher Chataway as an economic adviser.[4][3]: 55 He remained at the department until 1974.[26] In 1974, Morgan became the industrial development officer for South Glamorgan County Council, which he said was his "dream job".[4][3]: 59 He stopped working for the council in 1980.[4] From 1980 to 1987 Morgan worked at the European Commission's Office for Wales as the head of its press and information bureau.[17][7][28] His ability to speak German, Welsh and French proved useful.[4] In this role, he was the highest paid civil servant in Wales.[37]

Morgan's work had permitted him to keep living in Cardiff while staying politically active as a neutral civil servant.[18] However, he was still interested in partisan politics, and he was thinking about standing as an MP.[18][4] In 1985, Morgan decided to stand for parliament after his wife was elected as a councillor for South Glamorgan County Council.[18] James Callaghan had announced his plans to retire from his seat, Cardiff South and Penarth, at the next general election, and Morgan intended to take over from Callaghan as Labour's candidate for the seat.[3]: 67 However, another contender had already been promised local support by the Labour Party. Morgan was encouraged to seek selection in the seat of Cardiff West instead.[4] He was successfully nominated for selection as Labour's candidate in Cardiff West, beating contenders such as Ivor Richard, the United Kingdom's former ambassador to the United Nations, where he would stand in the 1987 general election.[28]

Parliamentary career

In the 1987 general election, Morgan was elected as the Labour MP for Cardiff West, defeating the incumbent Conservative MP Stefan Terlezki, who had been elected in the 1983 general election.[38][39] Morgan won the seat with a majority of 4,045 votes (9.1%).[40] He increased his majority to 9,291 (20.3%) in the 1992 general election[41] and 15,628 (38.8%) in the 1997 general election.[42] He was sponsored by the Transport and General Workers' Union[43] and shared an office at Transport House with Alun Michael, the Labour MP for Cardiff South and Penarth, following their election to parliament in 1987.[44] He was joined in parliament by his wife Julie following the 1997 general election, when she was elected as the Labour MP for Cardiff North.[45]

Morgan made his maiden speech in the House of Commons on 8 July 1987, during a debate on a Finance Bill.[46] The media developed a liking for Morgan; The Times reviewed the maiden speeches of the 1987 parliamentary intake and placed Morgan's maiden speech into joint-first place.[18] He established a reputation for being a "maverick" and a witty and outspoken "loose-cannon".[47] In line with the majority of backbench MPs from Wales,[48] Morgan aligned himself with the soft left of the Labour Party.[49][3]: 68 He was associated with the "Riverside Mafia", a group of soft left Labour councillors in South Glamorgan County Council which included Mark Drakeford, Jane Hutt, Sue Essex and Morgan's wife Julie.[29]: 4–5, 297 Morgan's main interests as an MP were industrial policy, regional policy, regional development, health, European affairs, the environment, and the conservation of wild life, particularly marine life and birds.[50] He also had an interest in freedom of information.[21]

Cardiff Bay Barrage campaign

An early challenge for Morgan during his parliamentary career was the controversial Cardiff Bay Barrage project. Mark Drakeford and Jane Hutt were suspended by the leadership of the Labour group in South Glamorgan County Council for opposing the scheme.[51][29]: 5 The council had been promoting the project with the Cardiff Bay Development Corporation, with both organisations claiming that the barrage would regenerate the Cardiff Docklands. Its opponents, meanwhile, claimed that it would be costly and potentially damaging to the environment.[52] Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock and Labour MP for Cardiff South and Penarth Alun Michael, whose constituency included the site where the new bay would be formed, both supported the project.[53] However, the constituency Labour Party for Cardiff West, Morgan's own constituency, had voted to oppose the barrage, and the local Labour Party branches for Riverside and Canton were also against it.[53]

On 3 July 1989, Morgan announced his opposition to the barrage, stating that it was wrong "to subject my constituents to disturbance for something of extremely doubtful value".[54] Morgan was concerned about the differing opinions from geologists on the barrage's possible effects.[54] He was a naturalist who found the bay's mudflats to be of value, and he believed that damming it could cause a permanent increase in drainage, damp and rot.[52][28] Morgan also believed that the barrage could flood Cardiff West,[47] with the constituency having had a history of damaging floods as recent as 1979.[52] He became the spokesman for a group of Labour councillors in Cardiff City Council and South Glamorgan County Council who opposed the project,[52] and in parliament he led a five year campaign against the bill which would allow for its construction.[28] Using parliamentary procedure and filibusters, Morgan was able to delay the construction of the barrage until the Conservative government finally pushed the bill through parliament in 1993.[55][28] Morgan's campaign against the bill generated animosity between him and Alun Michael, who had supported the barrage, and it made him appear less trustworthy to the more centrist-leaning elements of the Labour Party.[28] In 1993, Morgan warned John Redwood, the Welsh secretary, that a Labour government might stop the construction of the barrage before its completion. This prompted Michael to state that he was "fed up" with Morgan's "outrageous and irresponsible nonsense", adding that his remarks could deter employers from coming to Cardiff.[56]

Shadow ministerial career

In his first year in parliament, Morgan worked on standing committees for the Finance Bill, the Housing Bill and the Steel Privatisation Bill.[18] Labour leader Neil Kinnock rewarded Morgan for this work[18] by appointing him to Labour's shadow energy team on 10 November 1988.[57][58] He became a junior shadow minister for energy, where he was given responsibility for Labour's response to the government's electricity privatisation policy. When taking the role, Morgan said he intended to scrutinise the government's plans for electricity privatisation as he found "no virtues in converting a public monopoly into a private sector monopoly" and wanted to find "a better deal for consumers".[59] During Morgan's tenure, the shadow energy team opposed electricity privatisation.[60] He spoke beyond his brief, asking why Wales received less investment than Cornwall and Devon and exploring a now disproven conspiracy theory[61] that the Spandau prisoner believed to be Nazi German deputy Führer Rudolf Hess was an imposter.[28][62]

In the shadow energy team, Morgan initially worked under Tony Blair, the shadow secretary of state for energy from 1988 to 1989.[4][63] He then worked under Frank Dobson, the shadow energy secretary from 1989 to 1992.[47][64] According to The Independent, Morgan and Blair worked "harmoniously" together.[17] In contrast, the New Statesman said Morgan "antagonised [Blair] at every step".[65] Morgan himself believed that he was "highly regarded" by Blair.[60] He supported Blair's attempt to get elected to the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party in 1992 and voted for Blair during his campaign for the Labour leadership in 1994, which he won.[17][60]

On 30 July 1992, the recently elected Labour leader John Smith appointed Morgan as a shadow minister for Welsh affairs.[66] He remained in this post after Tony Blair became Labour leader in 1994.[67][68] At first, Morgan worked under Ann Clwyd, the shadow secretary of state for Wales from July 1992 to November 1992.[66][69] He then worked under Ron Davies, the shadow welsh secretary from November 1992, serving as his deputy.[29]: 3 He was also given responsibility for Labour's health policy in Wales.[70][71]

In the Welsh affairs brief, Morgan targeted quangos in Wales for their alleged cronyism, unaccountability and lack of democracy.[28][29]: 3 These quangos were unelected, publicly funded organisations whose leaders were appointed by the Conservative government.[72][29]: 3 Under John Redwood's tenure as Welsh secretary, the Welsh Office was criticised for presiding over a large increase over the amount of quangos in the country, with people sympathetic to the Conservative Party often appointed to lead them. In 1979, there were 44 quangos in Wales. By 1994, there were 111.[73] Quangos came to dominate Wales.[28] In 1994, Morgan claimed that government plans would result in there being more people sitting on quangos than local councillors in the country.[72] He refused to vote for the Welsh Language Act 1993; the act's main purpose was to set up a new quango called the Welsh Language Board. Morgan said Labour would abstain on the act "because we hope to have the opportunity before long to do the job properly. That will be done when we revisit the question of a Welsh language measure when we are in Government."[74] When William Hague was Welsh secretary, Morgan staged a protest with other Welsh Labour MPs outside the 1996 Conservative Party Conference, where he claimed that the total cost of the quangos in Wales had reached £51.5 million.[75]

To tackle the cost of the Welsh quangos, Morgan stated in 1996 that a devolved Welsh Assembly established by a Labour government would combine four quangos, the Welsh Development Agency, the Cardiff Bay Development Corporation, the Development Board for Rural Wales and the Land Authority for Wales to create an "economic powerhouse".[76] The idea of establishing a devolved Welsh Assembly had been supported by Morgan, who was one of its leading proponents.[77] He was involved in talks with the upper ranks of the Labour Party on devolution,[18] becoming an important figure in drawing up its devolution policy for Wales.[29]: 3 In the Welsh affairs brief, he campaigned for Welsh devolution,[8] helping move the proposal for a Welsh Assembly further up the Labour Party's policy platform.[78] He was a member of the Campaign for the Welsh Assembly[78] and supported Wales Labour Action, a pressure group within the Labour Party that called for the establishment of a Welsh Assembly.[79]: 40

Morgan's opposition to the Welsh quangos, as well as his attempts to stop the construction of the Cardiff Bay Barrage, alienated the traditionalists within the Labour Party in Wales. These actions also made him a known troublemaker towards the Welsh political establishment. In Cardiff, Morgan faced hostility from the local political establishment in the Labour Party.[29]: 3–4 He ultimately found the 1992–1997 parliament more challenging than the previous parliament.[4] He had a difficult relationship with some of Tony Blair's inner circle,[18] including his close confidant Alun Michael and his closest adviser Peter Mandelson.[60][77]

Return to the backbenches

In the 1997 general election, the Labour Party secured a landslide victory against the Conservative Party, returning to government after 18 years in opposition.[80] Morgan had been aspiring to become a government minister since at least 1994,[81] and when Labour returned to government he was expected to be given a role in the Welsh Office as a junior minister.[18][82] However, in what was viewed as a surprising decision, Prime Minister Tony Blair refused to give Morgan a role in the government.[83][84] Ron Davies, the Welsh secretary in the new government, had wanted to keep Morgan in his team as a junior minister, but Blair refused to appoint him to such a role.[85]: 23 At the time, Blair's official explanation was that Morgan, aged 57, was too old for a ministerial career.[60][86] However, in a 2017 interview with BBC News, Blair revealed that he did not appoint Morgan to the government because they disagreed on policy, adding that he viewed himself as a progressive politician bringing change while he viewed Morgan as a traditionalist.[84] Morgan returned to the backbenches[85]: 219 where he was elected chair of the House of Commons Public Administration Committee as a consolation prize.[21][87]

In his later parliamentary career as a backbencher, Morgan provoked the Labour government for its hesitance to ban the advertising of cigarettes, its unenthusiastic approach to freedom of information and for the party's parliamentary selection process.[28]

Welsh Labour leadership campaigns

Labour's election manifesto for the 1997 general election included a commitment to hold a devolution referendum in Wales to determine whether to establish a devolved Welsh assembly.[88] In the 1997 Welsh devolution referendum, Morgan campaigned for the Yes vote.[89] He was also considering standing for election to the assembly if the referendum passed.[77] The referendum resulted in a narrow majority in favour, which led to the passing of the Government of Wales Act 1998 and the formation of the devolved National Assembly for Wales in 1999. Morgan decided to put his name forward as Labour's candidate for the assembly seat of Cardiff West, which had the same name and boundaries as his seat in the House of Commons. He was subsequently identified as a likely contender to become the first leader of the assembly, known as the First Secretary of Wales.[90]

Following the result of the 1997 devolution referendum, Morgan immediately decided to run for the leadership of the Labour Party in Wales.[4] This meant that he was also running to become the inaugural first secretary of Wales, as Labour was expected to win the most seats in the first election to the assembly.[4][91] Leading the assembly had been a long-held ambition of Morgan's.[92][79]: 202 However, the favourite to become first secretary was the Welsh secretary Ron Davies, who was viewed as the architect of the government's plans for the devolved assembly.[93] In March 1998, Davies announced his intention to stand for a seat in the assembly and run for the post of first secretary.[94] Morgan then called for a leadership election to determine who the party's candidate for first secretary would be.[95] Senior figures in the Labour Party in Wales feared that a leadership election could split the party and instead preferred to avoid an election, with Davies running for the post of first secretary unopposed. However, Morgan continued to insist on a leadership election, stating that he had already announced his intention to become first secretary before Davies did.[95][79]: 202

Campaigning for the 1998 Welsh Labour leadership election began in March 1998 and lasted until September.[96] In his leadership pitch, Morgan cited his administrative experience in London, Europe, local government and the Welsh Office.[93] He also presented himself as the "new beginning, anti-establishment" candidate and as the "unity" candidate.[94][95] Davies had the support of Tony Blair and the party machinery of the Labour Party[4] and was viewed as the establishment candidate.[97] Morgan also presented himself as the "democratic" candidate, as he had campaigned for the election to be held under the one member, one vote electoral system.[97] However, senior figures in the Labour Party in Wales decided to hold the election under an electoral college with block voting, which was decried as "undemocratic" by Davies' opponents.[98] Support for Davies came from the large trade unions such as Unison and the Transport and General Workers' Union and from the majority of Labour MPs, MEPs and Welsh assembly candidates. Support for Morgan came from the smaller trade unions, the constituency membership and the party grassroots.[97] Ideologically, both Morgan and Davies were on the soft left of the Labour Party.[97]

In September 1998, Davies won the leadership election, therefore becoming the Labour Party in Wales' candidate for first secretary.[99] Morgan had won the most nominations from the constituency Labour parties,[4] as well as the membership vote across the constituency parties which held a membership ballot, but the electoral college left him with 31.78% of the vote to Davies' 68.22%.[99] Davies would resign from the cabinet and the leadership six weeks later after being involved in an alleged gay sex scandal on Clapham Common. Tony Blair appointed Alun Michael as Welsh secretary and planned for him to become the first secretary without a leadership election.[4] Blair appointed Michael, a Blairite, to prevent Morgan from taking the leadership.[18] Michael invited Morgan and another likely contender for the post, Wayne David, to serve with him as his deputies. Morgan declined Michael's offer and insisted on another leadership election.[92][4] Blair met with Morgan and tried to convince him not to stand, but Morgan rejected this appeal and continued his leadership campaign.[100][4]

The 1999 Welsh Labour leadership election took place in February 1999. It was a repeat of the 1998 leadership contest in several ways.[4] Morgan once again presented himself as the "anti-establishment" candidate. He also presented himself as the choice of the Welsh people. In contrast, Michael was widely seen as a reluctant parachute candidate from London who was imposed on Wales by the Labour Party leadership. In actuality, both Michael and Morgan were native Welsh speakers from Wales who shared a long-standing commitment to Welsh devolution. Morgan was described as the left-wing "Old Labour" candidate while Michael was described as the centrist "New Labour" candidate. Although Michael had by this point become a Blairite, both candidates had their origins in the soft left of the Labour Party. There was also some animosity between them, as Morgan had been a leading campaigner against the Cardiff Bay Barrage project while Michael had been a leading campaigner in support of it.

Assembly career

First Assembly (1999)

| |

| Premiership of Rhodri Morgan 9 February 2000 – 10 December 2009 | |

Rhodri Morgan | |

| Cabinet | Interim government 1st government 2nd government 3rd government 4th government |

| Party | Welsh Labour Party |

| Election | 2003, 2007 |

| Appointed by | Elizabeth II |

| Seat | Tŷ Hywel |

|

| |

A committed supporter of Welsh devolution, Morgan contested the position of Labour's nominee for the (then titled) First Secretary for Wales. He lost to the then Secretary of State for Wales, Ron Davies. Davies was then forced to resign his position after an alleged sex scandal, whereupon Morgan again ran for the post. His opponent, Alun Michael, the new Secretary of State for Wales, was seen as a reluctant participant despite also having a long-standing commitment to Welsh devolution, and was widely regarded as being the choice of the UK leadership of the Labour Party.[101]

Michael was duly elected to the leadership but resigned a little more than a year later, amid threats of an imminent no-confidence vote and alleged plotting against him by members of not only his own party, but also Assembly groups and Cabinet members. Morgan, who had served as Minister for Economic Development under Michael,[82] became Labour's new nominee for First Secretary, and was elected in February 2000, later becoming First Minister on 16 October 2000 when the position was retitled. He was also appointed to the Privy Council in July 2000.[102]

Morgan stepped down from the House of Commons at the 2001 General Election.

Morgan's leadership was characterised by a willingness to distance himself from a number of aspects of UK Labour Party policy, particularly in relation to plans to introduce choice and competition into public services, which he has argued do not fit Welsh attitudes and values, and would not work effectively in a smaller and more rural country. In a speech given in Swansea to the National Centre for Public Policy in November 2002, Morgan stated his opposition to foundation hospitals (a UK Labour proposal), and referred to the "Clear Red Water"[103] separating policies in Wales and in Westminster.[104]

Second Assembly (2003)

On 1 May 2003, Labour under Morgan's leadership was re-elected in the Assembly elections. Morgan managed to win enough seats to form a Labour-only administration (the election was held under proportional representation, and Labour won 30 of the 60 seats in the Assembly and the overall majority was achieved when Dafydd Elis-Thomas AM was elected Presiding Officer of the Assembly) and named his cabinet on 9 May. In that election, Labour easily took back all of the former strongholds they lost to Plaid Cymru at the height of Alun Michael's unpopularity in 1999.

In his second term, Morgan's administration continued its theme of "Welsh solutions for Welsh problems", a marked contrast to the Blairite public service reform agenda.[citation needed] Instead of competition, Welsh Labour emphasised the need for collaboration between public service providers.[105]

Third Assembly (2007)

Labour was the biggest party with 26 out of the 60 seats, five short of an overall majority. After one month of minority government, Morgan signed a coalition agreement (One Wales) with Ieuan Wyn Jones, leader of Plaid Cymru, on 27 June 2007. Morgan became the first modern political leader of Wales to lead an Assembly with powers to pass primary legislation (subject to consent from Westminster).[citation needed]

Retirement

In July 2005, Morgan announced his intention to lead the Welsh Labour party into the 2007 general election, but retire as leader of Welsh Labour and First Minister sometime in 2009, when he would be 70.[106] On his 70th birthday (29 September) he set the exact date as immediately following the Assembly's budget session on 8 December 2009.[107] Counsel General Carwyn Jones, Health Minister Edwina Hart and Merthyr Tydfil and Rhymney AM Huw Lewis entered a leadership contest to elect a new Labour leader in Wales.[108] On 1 December 2009 the winner was declared as Carwyn Jones,[109] who assumed office as First Minister on 10 December 2009. Morgan remained a backbench AM until April 2011, when the third Assembly was dissolved before the general election on 5 May 2011.

Personal life

Morgan married Julie Morgan (née Edwards) in 1967. Julie would later have her own political career as an AM and MP, joining Morgan in the House of Commons in 1997.[4][45] The couple had two daughters, Mari and Siani, and an adopted son, Stuart. Mari was born in 1968 and became a scientist while Siani was born in 1969 and became a charity worker.[7] Stuart, born in 1969 or 1970,[33] was troubled and had multiple convictions.[7] Morgan also had eight grandchildren[110] and a Labrador named William Tell.[111][112] His elder brother Prys Morgan was a history professor at Swansea University[18] and his second cousin Garel Rhys was an academic.[1]

After marriage, Morgan settled at Dinas Powys. From 1986, he then lived with his wife and children at Lower House, a former farmhouse in the countryside of Michaelston-le-Pit.[113][16] The home was known for being untidy and disorganised,[113] with friends reportedly describing it as a "tip".[114] The couple also had a caravan in Mwnt, on the coast of Ceredigion, where the family holidayed each summer for at least 40 years.[82][115] Morgan was a long-time friend of Neil Kinnock, leader of the Labour Party from 1983 to 1992.[116][3]: 299 In their younger years, they were part of a rock band together.[117] They shared a flat in Cardiff from 1963 to 1965.[7] Morgan was also a long-time friend of the former AM Sue Essex.[118]

In July 2007, Morgan had an unstable angina which caused a partial blockage in two of his arteries and a heart attack.[119][29]: 20 He was admitted to hospital where he underwent cardiac surgery and had two stent implants to unblock his arteries.[120][121] Even though he left hospital within the week, doctors said he would not be fully recovered for a few weeks.[122]

Death

Morgan collapsed on the evening of 17 May 2017 while cycling on Cwrt yr Ala Road, Wenvoe, near his home. Police and paramedics were called to the scene and he was pronounced dead.[123] He was 77.[124]

Morgan's family held a humanist funeral for him, in line with his humanist beliefs, at the Welsh Assembly on 31 May, which was open on a first-come first-served basis to the public, as well as broadcast on screens outside the Senedd and online. The funeral was televised and billed as a major national event. The ceremony was led by Morgan's friend and former Welsh Labour colleague Lorraine Barrett.[125][126] A private service of committal was held at Thornhill Crematorium's Wenallt Chapel in Cardiff the next day.

Honorary degrees

Morgan was awarded several honorary degrees for his service to the United Kingdom, including the following.

| Country | Date | School | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| 26 November 2007 | University of Wales | Honorary Doctor of Laws (LL.D)[127] | |

| June 2009 | Bangor University | Honorary Doctorate[128] | |

| 2009 | Aberystwyth University | Honorary Fellow[129] | |

| 2010 | Cardiff University | Honorary Doctorate[130] | |

| 2010 | Swansea University | Honorary Doctorate[131] | |

| July 2011 | University of Glamorgan | Honorary Doctorate[132] |

He was also appointed Chancellor of Swansea University in 2011, a post he held until his death. He had close links with the university as both his parents had graduated from it in the 1920s and his father and brother also taught there.[133]

References

Notes

- ^ First Secretary until 2006

- ^ In 2017, following Morgan's death, the website for the community of Radyr and Morganstown claimed that he was born in Radyr.[1] In his 1994 book Cardiff: Half-and-half a Capital, Morgan states that he was in fact born in Roath and that Radyr was where he was raised.[2]: 8 In his 2017 autobiography Rhodri: A Political Life in Wales and Westminster, Morgan specifies that he was born at Mrs Gill's Nursing Home,[3]: 40–41 which was located at 88 Connaught Road, Roath.[4]

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Rhodri Morgan (29 September 1939 – 17 May 2017)". Radyr & Morganstown Community. 18 May 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ a b Morgan, Rhodri (1994). Cardiff: Half-and-half a Capital. Gomer Press. ISBN 978-1-85902-112-5. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Morgan, Rhodri (15 September 2017). Rhodri: A Political Life in Wales and Westminster. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-1-78683-148-4. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Hyman, Gavin (14 January 2021). "Morgan, (Hywel) Rhodri (1939–2017)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.013.90000380313. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Brynley Francis (11 May 2016). "MORGAN, THOMAS JOHN (1907–1986), Welsh scholar and writer". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Shipton, Martin (12 January 2010). "Rhodri Morgan's brother spills the beans". WalesOnline. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Obituary: Rhodri Morgan". The Times. 19 May 2017. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ a b c "Rhodri Morgan (1939–2017): Humanist, first First Minister of Wales, and father of Welsh devolution". Humanists UK. 18 May 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ a b "Rhodri's mum dies aged 99". WalesOnline. 27 December 2005.

- ^ a b McKie, Andrew (19 May 2017). "Obituary – Rhodri Morgan, Welsh politician". The Herald. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Academi Gymreig (Welsh Academy) (January 2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopaedia of Wales. University of Wales Press. p. 571. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.

- ^ "From turning down a peerage to being a proud grandfather – Rhodri Morgan in his last interview". ITV News. 19 June 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "'Rhodri had always nursed the possibility that he would see some sort of dawn of revolution'". Western Mail. 12 November 2022. pp. 6–9. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "First Minister Meets His Czech Mates". Welsh Assembly Government. 28 June 2002. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ a b "WWII display targets the young". BBC News. 19 February 2005. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ a b Bodden, Tom (10 August 2011). "Rhodri Morgan talks about his retirement passion for his garden". North Wales Live. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d McSmith, Andy (18 May 2017). "Rhodri Morgan, obituary: Former Welsh First Minister nicknamed the 'father of the nation'". The Independent. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Phillips, Ioan (20 July 2021). "MORGAN, HYWEL RHODRI (1939–2017), politician". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Morgan's "fuzzy" childhood". BBC News. 8 December 2009. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ a b Williams, Tryst (1 March 2006). "What I remember is all us boys taking leeks to school". WalesOnline. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Clement, Barrie (13 February 1999). "The Saturday Profile: Rhodri Morgan, MP for Cardiff West: The clown prince of Wales". The Independent. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Rhodri sees his friends reunited". WalesOnline. 12 August 2006. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Notable Alumni". Whitchurch High School. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Williamson, David (23 May 2017). "Rhodri Morgan refused to spruce up or dumb down but lived with authenticity". WalesOnline. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ Phillips, Rob (9 August 2021). "Rhodri Morgan in America". National Library of Wales. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ a b c "People in the Assembly: Rhodri Morgan". BBC News. 1 September 1999. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ Powys, Betsan (7 May 2009). "Betsan's blog: Asking Rhodri". BBC News. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Rhodri Morgan, former First Minister of Wales – obituary". The Daily Telegraph. 18 May 2017. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Williams, Jane; Eirug, Aled (15 June 2022). The Impact of Devolution in Wales: Social Democracy with a Welsh Stripe?. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-1-78683-887-2. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Morgan and Kinnock fondly recall fighting the 1964 election". WalesOnline. 28 March 2005. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ a b Drower, G. M. F. (3 October 1994). Kinnock: A Biography. South Woodham Ferrers: The Publishing Corporation. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-897780-41-1. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ Morgan, Rhodri (7 December 2013). "Nelson Mandela: Rhodri Morgan on the fateful 1964 day when Wales prayed for Mandela's life". WalesOnline. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ a b "MPs' son jailed for assault on girlfriend". The Herald. 17 June 1997. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ "Maverick who shaped post-devolution Wales". WalesOnline. 26 April 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ Hargreaves, Ian (29 January 1999). "Profiles: Rhodri Morgan". New Statesman. Vol. 128, no. 4421. p. 18. ISSN 1364-7431.

- ^ "Rhodri Morgan: Lab Cardiff West". BBC News. 1997. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ Rosen, Greg (2001). Dictionary of Labour Biography. London: Politico's. pp. 419–420. ISBN 978-1-902301-18-1. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ Roth, Andrew (1 March 2006). "Obituary: Stefan Terlezki". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Stefan will be much missed". WalesOnline. 23 February 2006. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Wood, Alan H. (June 1987). The Times Guide to the House of Commons. Times Newspapers Limited. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-7230-0298-7. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Wood, Alan H.; Wood, Roger (April 1992). The Times Guide to the House of Commons. Times Newspapers Limited. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-7230-0497-4. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Waller, Robert; Criddle, Byron (1999). The Almanac of British Politics. Psychology Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-415-18541-7. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Balsom, Denis (1995). The Wales Yearbook 1995. HTV Cardiff. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-9500-4297-8. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Woodward, Will (15 February 1999). "Divisive battle revives old emnity". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Rhodri Morgan – Third time lucky". BBC News. 11 February 2000. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Morgan, Rhodri (8 July 1987). "Orders of the Day — Finance Bill: Contribution from Mr Rhodri Morgan, Cardiff West". Hansard. 381. Retrieved 8 April 2023 – via TheyWorkForYou.

- ^ a b c Roth, Andrew (16 March 2001). "Rhodri Morgan". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

From his maiden speech his brilliance was not in doubt. But he was seen as a maverick, a 'loose cannon' who tended to strike out wittily.

- ^ Waugh, Paul (6 November 1998). "The Davies Affair: Maverick will not toe the line". The Independent. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ "Separate slots for Welsh rivals". The Guardian. 31 August 1998. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Bedford, Michael (January 1990). "Dod's Parliamentary Companion 1990: 158th Year". Dod's Parliamentary Companion. 171. London: 520. ISBN 978-0-905702-16-2. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Horton, Nick (27 April 1989). "Bay rebels: Why we voted No". South Wales Echo. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Powell, Kenneth (3 March 1990). "The barrage of controversy". The Daily Telegraph. No. 41, 893. p. 51. ISSN 0307-1235.

- ^ a b "Now Rhodri Morgan has to do some convincing". South Wales Echo. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. 4 July 1989. p. 10.

- ^ a b Arnold, Mike (4 July 1989). "'Best news' on barrage". South Wales Echo. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. p. 2.

- ^ "Commons blamed for Bay delay". BBC News. 16 March 2000. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Wright, Geoff (16 November 1993). "'Bay may not stay'". South Wales Echo. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. p. 7.

- ^ Millward, David (11 November 1988). "Kinnock gives Blunkett job on Front Bench". The Daily Telegraph. No. 41, 487. p. 18. ISSN 0307-1235.

- ^ Rose, David (11 November 1988). "Kinnock beefs up Welsh team". Daily Post. Wrexham, Clwyd. p. 5.

- ^ "S. Wales MPs set for action". South Wales Echo. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. 14 November 1988. p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e Shipton, Martin (11 May 1997). "'It seems Tony Blair has no sense of obligation to me for helping him construct his glittering career'". South Wales Echo. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. pp. 20–21.

- ^ "Rudolf Hess: DNA test disproves Spandau prison conspiracy theory". BBC News. 22 January 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "Mystery of Spandau's prisoner No 7". The Herald. 4 April 1998. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Mardell, Mark (26 May 2016). "Ghost of Blair continues to haunt Labour". BBC News. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ Dod, Charles Roger; Dod, Robert Phipps (2007). Dod's Parliamentary Companion 2007: 175th Year. London: Dod's Parliamentary Companion. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-905702-66-7. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ Parrish, Duncan (27 November 1998). "Rhodri Morgan". New Statesman. Vol. 127, no. 4413. p. 34. ISSN 1364-7431.

- ^ a b Rose, David (31 July 1992). "Marek rejects front bench job". Daily Post. Wrexham, Clwyd. p. 4.

- ^ Shrimsley, Robert (27 October 1994). "Blair puts women in key junior posts". The Daily Telegraph. No. 43, 342. p. 9. ISSN 0307-1235.

- ^ Hibbs, Jon (7 November 1998). "A welcome in the hillsides – but not at No10". The Daily Telegraph. No. 44, 600. p. 12. ISSN 0307-1235.

- ^ "MPs and Lords: Ann Clwyd". UK Parliament. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ "Keynote speech by Blair". South Wales Echo. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. 28 February 1997. pp. 18–19.

- ^ McSmith, Andy (20 February 1994). "Health chief's resignation fuels row over quangos". The Observer. No. 10558. p. 10.

- ^ a b "Dam irony of Aberpergau". Wales on Sunday. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. 6 March 1994. p. 15.

- ^ Purnell, Sonia (31 May 1994). "Redwood fails to stem the flood of scandal". The Daily Telegraph. p. 11. ISSN 0307-1235.

- ^ "New Welsh Language Act – A Real Opportunity!: Proposals for a New Welsh Language Act" (PDF). Welsh Language Act Campaign Group. November 2005. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ "Labour's counter attack". South Wales Echo. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. 25 November 1996. p. 12.

- ^ Linford, Paul (21 March 1996). "Hague sets tough aim for quangos". South Wales Echo. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. p. 21.

- ^ a b c Shipton, Martin (3 August 1997). "Crown him King Rhodri of Wales". Wales on Sunday. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Deacon, Russell (30 September 2012). Devolution in the United Kingdom. Edinburgh University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-7486-6973-8. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Jones, James Barry; Balsom, Denis (2000). The Road to the National Assembly for Wales. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1492-0. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ "Labour routs Tories in historic election". BBC News. 2 May 1997. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ Linford, Paul (25 July 1994). "Rhodri's Cardiff is essential reading: Cardiff: Half and Half a Capital book review". South Wales Echo. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. p. 17.

- ^ a b c Hannan, Patrick (18 May 2017). "Rhodri Morgan obituary". The Guardian. (posthumous). Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ "Welsh MP Snubbed As Referendum Plans Take Place". Local Government Chronicle. 7 May 1997. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ a b Servini, Nick (11 September 2017). "Blair and his steamrollered devolution". BBC News. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ a b Deacon, Russell (2002). The Governance of Wales: The Welsh Office and the Policy Process 1964–1999. Welsh Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-86057-039-1. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ Cornock, David (10 May 2007). "Blair waves last goodbye to Wales". BBC News. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ Morgan, Rhodri (16 July 2011). "Brooks raises awkward questions for Murdochs". NorthWalesLive. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ "History of devolution". Welsh Parliament. 12 July 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ Ridd, Susan (13 September 1997). "Voters urged to seize opportunity for Wales". South Wales Echo. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. p. 2.

- ^ "MP to bid for assembly". South Wales Echo. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. 25 October 1997. p. 4.

- ^ "Davies beats off backbench challenge". BBC News. 19 September 1998. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- ^ a b Womersley, Tara; Smale, Will (6 November 1998). "Alun Michael makes bid to lead assembly". South Wales Echo. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. p. 23.

- ^ a b "Davies is favourite to lead an assembly". South Wales Echo. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. 19 September 1997. p. 9.

- ^ a b Ward, Lucy (31 March 1998). "Ron Davies wants to be Wales prime minister". The Guardian. p. 2. ISSN 0261-3077.

- ^ a b c Shipton, Martin (5 April 1998). "Battle for Assembly leadership could split Labour". Wales on Sunday. Cardiff, South Glamorgan. p. 4.

- ^ Morgan, Kevin; Mungham, Geoff (2000). Redesigning Democracy: The Making of the Welsh Assembly. Seren. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-85411-283-5. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d MacAskill, Ewen (17 September 1998). "Davies faces hollow victory in Wales". The Guardian. p. 9. ISSN 0261-3077.

- ^ Berry, Brendan (4 August 1998). "Ron Davies set to become First Secretary of Wales". The Independent. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ a b Shipton, Martin (20 September 1998). "Poll victory puts Ron within reach of the title of Welsh First Secretary". Wales on Sunday. pp. 4–5.

- ^ Powell, Nick (25 July 2020). "Power struggles revealed in Rhodri Morgan's memoirs". ITV News. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ Guto Harri (9 February 2000). "Q&A: The Alun Michael vote". BBC News. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ "Morgan made privy councillor". BBC News. 24 July 2000. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ "Clear Red Water: Rhodhri Morgan's speech to the National Centre for Public Policy Swansea". Socialist Health Association. 11 December 2002. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "New Labour 'attack' under fire". BBC News. 11 December 2002. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ Welsh Assembly Government. "Making the Connections". Archived from the original on 3 April 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ "Morgan is stepping down as leader". BBC News. 1 October 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Morgan plans to step down in 2009". BBC News. 13 July 2005. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Two join race to succeed Morgan". BBC News. 2 October 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "Carwyn Jones clinches leadership in Wales". WalesOnline. 1 December 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ Mosalski, Ruth (30 May 2017). "'He wouldn't like us to be sorrowful' In her first interview since his death, Rhodri Morgan's wife describes her shock and heartbreak". WalesOnline. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ "Portraits of Rhodri Morgan at work and play unveiled". BBC News. 26 January 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ "Senedd tribute to Rhodri Morgan unveiled". South Wales Argus. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ a b Underwood, Peter (25 February 1987). "Marathon man runs for a new Lower House...". South Wales Echo. Cardiff, South Glamorgan.

- ^ Watt, Nicholas (10 February 2000). "Morgan earns his spurs". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ "I'm still in charge, says Morgan". BBC News. 11 August 2009.

- ^ Kinnock, Neil (21 May 2017). "Me and my old friend Rhodri Morgan". WalesOnline. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ Moncur, Andrew (23 June 1989). "Diary". The Guardian. p. 23.

- ^ Shipton, Martin (19 July 2018). "Friends of Rhodri Morgan want a statue of him in Cardiff Bay". WalesOnline. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Bodden, Tom (24 December 2007). "Rhodri Morgan gets fit for office after heart scare". North Wales Live. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ Shipp, Tom (10 July 2007). "Plaid leader to become Wales's deputy first minister". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ "Post-op Morgan says 'I'm lucky'". BBC News. 11 July 2007. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ Mulholland, Hélène (9 July 2007). "Rhodri Morgan spends night in hospital". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ Owen, Cathy (18 May 2017). "Rhodri Morgan collapsed and died cycling". Western Mail. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ "Rhodri Morgan: Tributes to Wales' former first minister". BBC News. 17 May 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ "Public humanist funeral for Rhodri Morgan at National Assembly for Wales". Humanists UK. 31 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ "Rhodri Morgan funeral to be held at the Senedd, Cardiff". BBC Wales News. 31 May 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ "Rhodri set to receive an honorary degree". WalesOnline. 26 November 2007.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees". Bangor University. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ "Honorary Awards". Aberystwyth University.

- ^ "Honorary Fellows". Cardiff University.

- ^ Williamson, David (2 April 2013). "Swansea University honour for Rhodri Morgan". WalesOnline. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Honorary doctorate for former First Minister Rhodri Morgan". WalesOnline. 22 March 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Rhodri Morgan becomes Swansea University chancellor". BBC News. 25 October 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2022.