Retrogaming

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

Retrogaming, also known as classic gaming and old school gaming, is the playing and collection of obsolete personal computers, consoles, and video games. Usually, retrogaming is based upon systems that are outmoded or discontinued, although ported retrogaming allows games to be played on modern hardware via ports or compilations. It is typically for nostalgia, preservation, or authenticity. A new game could be retro styled, such as an RPG with turn-based combat and pixel art in isometric camera perspective.

Retrogaming has existed since the early years of the video game industry, and was popularized with the Internet and emulation technology.[1] It is argued that the main reasons players are drawn to retrogames are nostalgia for different eras,[2] the idea that older games are more innovative and original,[2] and the simplicity of the games.

Retrogaming and retrocomputing have been described as preservation activity and as aspects of the remix culture.[3]

Games

The distinction between retro and modern is heavily debated, but it usually coincides with either the shift from 2D to 3D games (making the fourth the last retro generation, and the fifth the first modern), the turn of the millennium and the increase in online gaming (making the fifth the last retro generation, and the sixth the first modern), or the switch from analog to digital for audiovisual output and from 4:3 to 16:9 aspect ratio (making the sixth the last retro generation, and the seventh the first modern). They can be played on original hardware or in modern emulation.

Retrogaming methods

With increasing nostalgia and success of retro compilations in the fifth, sixth, and seventh generations of consoles, retrogaming has become a motif in modern games. Modern retrogames impose limitations on color palette, resolution, and memory well below the actual limits of the hardware, to mimic the look of old hardware. These may be based on a general concept of retro, as with Cave Story, or an attempt to imitate a specific piece of hardware, as with MSX color palette of La Mulana.

This concept, known as deliberate retro[4] and NosCon,[5] gained popularity due part to the independent gaming scene,[6] where the short development time was attractive and commercial viability was not a concern. Major publishers have embraced modern retrogaming with releases such as Mega Man 9 which mimics NES hardware; Retro Game Challenge, a compilation of new games on faux-NES hardware; and Sega's Fantasy Zone II remake, which uses emulated System 16 hardware running on PlayStation 2 to create a 16-bit reimagining of the 8-bit original.

Vintage retrogaming

Vintage retrogaming can involve collecting original cartridge and disc media[8] and arcade and console hardware, which can be expensive and rare.[9][10] Most are priced lower than their original retail prices.[11] The popularity of vintage retrogaming has led to counterfeit media, which generally lack collectible value.[11] During the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, prices for vintage hardware began spiking to much higher levels than pre-pandemic, mostly attributed to the millennial generation pursuing the hobby during the lockdown due to boredom and nostalgia.[12]

Retrogaming emulation

Retrogaming may involve older game systems being emulated on modern hardware. It bypasses the need to collect older consoles and original games. Read-only memory (ROM) files are copied by third parties, directly from the original media. They are then typically put online through file sharing sites.[8] They are often sold as re-releases, typically in compilations containing multiple games running on emulation software.[13] The accessibility of emulation popularized and expanded on retrogaming.[14]

Ported retrogaming

Ported retrogaming involves original games being converted to native on new systems, just as emulation but without original ROM files.[8] Ported games are available through official collections, console-based downloads, and plug and play systems.[14] Ported retrogaming is comparatively rare, since emulation is a much easier and more accurate method.

Remakes

Modern retrogaming may be more broadly applied to retro-style designs and reimaginings with more modern graphics. These enhanced remakes include Pac-Man: Championship Edition, Space Invaders Extreme, Super Mega Worm, and 3D Dot Game Heroes. Some are based directly upon the enhanced emulation of original games, as with Nintendo's NES Remix.

When remakes are created by an individual or a group of enthusiasts without commercial motivation, such games sometimes are also called fangames. These are often motivated by the phenomenon of abandonware, which is the discontinuation of sales and support by the original producers. Examples of fan-made remakes are King's Quest I: Quest for the Crown, King's Quest II: Romancing the Stones, and Freeciv.

The nostalgia-based revival of past game styles has also been accompanied by the development of the modern chiptune genre of game music. Chiptunes are characterized by severe limitations of sound imposed by the author's self-restriction to using only the original sound chips from 8-bit or 16-bit games. These compositions are featured in many retro-style modern games and are popular in the demoscene.

Re-releases

With the new possibility of the online distribution in mid-2000, the commercial distribution of older games became feasible, as deployment and storage costs dropped significantly:

... we can put something up on Steam [a digital distributor], deliver it to people all around the world, make changes. We can take more interesting risks ... Retail doesn't know how to deal with those games. On Steam there's no shelf-space restriction. It's great because they're a bunch of old, orphaned games

A digital distributor specialized in bringing older games out of abandonware is GOG.com (formerly called Good Old Games) who started 2008 to search for copyright holders of older games to re-release them legally and DRM-free.[17] Other companies have also been established to rerelease retro games, including Limited Run Games and iam8bit.[18]

Online platforms for older video games re-releases include Nintendo's Virtual Console and Sony's PlayStation Network.

Mobile application developers have been purchasing the rights and licensing to re-release older arcade games on iOS and Android operating systems. Some publishers are creating spinoffs to their older games, keeping the core gameplay while adding new features, levels, and styles of play.

Plug-and-play systems

Plug-and-play systems have been released or licensed by companies such as Atari, Sega, and Nintendo. These systems include stand-alone game libraries and plug directly into the user's television.[8]

Retrogaming community

The retrogaming market is active with online and physical spaces where retrogames are discussed, collected, and played.[14]

Online

Several websites and online forums are devoted to retrogaming. The content on these online platforms typically includes reviews of older games, interviews with developers, fan-made content, game walkthroughs, and message boards for discussions.[14] Many gameplay videos posted online feature attempts at breaking speedrun or high score records.

Fighting games

The competitive Fighting game community comes from arcades, such as Street Fighter and Mortal Kombat.[19] Some fighting games have continued to receive arcade releases after the end of the arcade era.[20] Face-to-face competition of Super Street Fighter II Turbo has been featured in the Evolution Championship Series.[21]

Exhibitions

Events typically include vendors, gameplay, tournaments, costumes, and live music. The Classic Tetris World Championship has been streamed online to millions of views and recaps have been broadcast on ESPN2.[22]

Museums

Retrogaming is recognized by museums worldwide. For example, the RetroGames arcade museum of Karlsruhe, Germany was founded in 2002[23][24] and the Computerspielemuseum Berlin was founded in 1997. Some classical art museums bear a video gaming retrospective, as with 2012's Smithsonian American Art Museum exhibition titled The Art of Video Games[25] or as part of the Museum of Modern Art "Applied Design" exhibition in 2013.[26] Starting in 2015, The Strong National Museum of Play adds games annually to the World Video Game Hall of Fame. In 2016, the first museum dedicated solely to the history of the videogame industry, The National Videogame Museum, was opened in Frisco, Texas.

Legal issues

An exemption in the United States' Digital Millennium Copyright Act allows consumers to modify video games they already own to make them playable.[27] However, the duration of copyright on creative works in most countries is far longer than the era of home computing, leading to criticism that software piracy is the only way to preserve some titles. In some cases, such as No One Lives Forever, the rights remain ambiguous, preventing legal distribution.[28]

Emulators are typically created by third parties, and the software they run is often taken directly from the original games and put online for free download.[8] While it is completely legal for anyone to create an emulator for any hardware, unauthorized distribution of the code for a retro game is an infringement of the game's copyright.[29] Some companies have made public statements, such as Nintendo, stating that "the introduction of emulators created to play illegally copied Nintendo software represents the greatest threat to date in the intellectual property rights of video game developers".[30] However, video game developers and publishers typically ignore emulation.[8] One reason for this is that at any given time, most of the games illegally distributed for emulation are not presently being sold by the company which owns the game, and so the financial damages in a successful lawsuit would likely be negligible.[29]

Copyright infringement cases

Nintendo of America Inc. v. Tropic Haze LLC, No.

Nintendo filed a lawsuit in 2024 against Tropic Haze, claiming Yuzu, Tropic Haze's emulator, infringed copyright by reverse engineering Nintendo's hardware. The settlement included Tropic Haze paying $2.4 million and halting their emulator projects.[31][32][33]

Nintendo of America Incorporated v. Mathias Designs LLC.

Nintendo sued the owner of LoveROMs.com and LoveRETRO.co in 2018 for hosting copyrighted game files and facilitating piracy. The court awarded Nintendo $12,230,000 in damages, leading to the shutdown of the sites.[34][35][36]

Sony Computer Entertainment Inc. v. Connectix Corp.

In 1999, Sony sued Connectix, the court issued a preliminary injunction against Connectix for copyright infringement on their Virtual Game Station, an emulator enabling PC users to play PlayStation games, violating Sony's BIOS copyright.[37][38][39]

Sega Enterprises Ltd. v. Accolade, Inc.

Sega Enterprises sued Accolade in 1992 for reverse engineering Sega's technology to develop compatible games for the Sega Genesis console. The court sided with Accolade, supporting certain reverse engineering efforts for compatibility.[37][40]

Lewis Galoob Toys, Inc. v. Nintendo of America, Inc.

In 1992, Lewis Galoob Toys was sued by Nintendo over the Game Genie, a device allowing game modifications for personal use. The 9th District Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Lewis Galoob Toys, stating such modifications did not infringe copyright, permitting the continued sale of the Game Genie.[37][41]

See also

- Video game collecting

- List of retro style video game consoles

- History of arcade video games

- History of mobile games

- History of video game consoles

- Halcyon Days: Interviews with Classic Computer and Video Game Programmers

- MAME, multi-system emulator

- Old School Revival

- Retrocomputing

References

- ^ Heineman, David S. (January 22, 2014). "Public Memory and Gamer Identity: Retrogaming as Nostalgia". Journal of Games Criticism. Vol. 1, no. 1. pp. 1–24. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ a b "Revival of the Fittest". Next Generation. No. 28. Imagine Media. April 1997. pp. 36–45.

- ^ Yuri Takhteyev; Quinn DuPont (2013). "Retrocomputing as Preservation and Remix" (PDF). IConference 2013 Proceedings. University of Toronto: 422–432. doi:10.9776/13230 (inactive January 31, 2024). hdl:2142/38392. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 13, 2018. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

This paper looks at the world of retrocomputing, a constellation of largely non-professional practices involving past computing technology. Retrocomputing includes many activities that can be seen as constituting 'preservation.' At the same time, it is often transformative, producing assemblages that 'remix' fragments from the past with newer elements or joining together historic components that were never combined before. While such 'remix' may seem to undermine preservation, it allows for fragments of computing history to be reintegrated into a living, ongoing practice, contributing to preservation in a broader sense. The seemingly unorganized nature of retrocomputing assemblages also provides space for alternative 'situated knowledges' and histories of computing, which can sometimes be quite sophisticated. Recognizing such alternative epistemologies paves the way for alternative approaches to preservation.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link) - ^ "Deliberately Retro". giantbomb.com. Archived from the original on December 27, 2016. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- ^ "NosCon". giantbomb.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ "9 indie games shamelessly inspired by retro ancestors". gamesradar.com. April 25, 2014. Archived from the original on November 1, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ "Crippled by Nostalgia: The Fraud of Retro Gaming". Eurogamer. September 12, 2012. Archived from the original on December 31, 2014. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f "What is Retrogaming?". wiseGEEK. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ "What Happened to Classic Video Game Packaging? - IGCritic". Archived from the original on November 6, 2016.

- ^ "The Rarest and Most Valuable Super Nintendo (SNES) Games". February 21, 2018. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ^ a b "The Real Thing". Next Generation. No. 28. Imagine Media. April 1997. pp. 44–45.

- ^ Heubl, Ben (May 12, 2020). "Retro-gaming boom during lockdown". Institution of Engineering and Technology. Archived from the original on January 25, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ^ "Classic Game Collections". Next Generation. No. 28. Imagine Media. April 1997. pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b c d Heineman, David S. (January 22, 2014). "Public Memory and Gamer Identity: Retrogaming as Nostalgia". Journal of Games Criticism. Vol. 1, no. 1. pp. 1–24. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

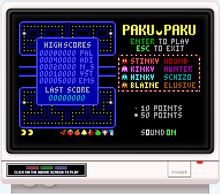

- ^ Knight, Jason. "Paku Paku – A game for early PC/MS-DOS Computers". deathshadow.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ Walker, John (November 22, 2007). "RPS Exclusive: Gabe Newell Interview". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

The worst days [for game development] were the cartridge days for the NES. It was a huge risk – you had all this money tied up in silicon in a warehouse somewhere, and so you'd be conservative in the decisions you felt you could make, very conservative in the IPs you signed, your art direction would not change, and so on. Now it's the opposite extreme: we can put something up on Steam, deliver it to people all around the world, make changes. We can take more interesting risks.... Retail doesn't know how to deal with those games. On Steam [a digital distributor] there's no shelf-space restriction. It's great because they're a bunch of old, orphaned games.

- ^ Caron, Frank (September 9, 2008). "First look: GOG revives classic PC games for download age". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on December 20, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

... [Good Old Games] focuses on bringing old, time-tested games into the downloadable era with low prices and no DRM.

- ^ Thorpe, Nick (January 1, 2021). "Let's get physical: Meet the companies reissuing retro classics for audiences new and old". GamesRadar. Archived from the original on January 1, 2021. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Bowman, Mitch (February 6, 2014). "Why the fighting game community is color blind". Polygon. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "A Brief History of 2D Fighting Games". Archived from the original on October 2, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Walker, Ian. "Evo 2015 Super Street Fighter II Turbo Side Tournaments Unveiled, Registration Now Live". Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "Organize This - Talking Tetris Champs With Vincent Clemente". www.twingalaxies.com. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

- ^ "RetroGames e.V. | Erhalt und Pflege der Videospielkultur in Deutschland". www.retrogames.info (in German). Retrieved December 16, 2023.

- ^ Schmitz, Peter (July 19, 2002). "Erster eingetragener Verein für Computer- und Konsolenspiele-Oldies eröffnet" (in German). Heise.de. Archived from the original on November 21, 2007. Retrieved June 1, 2012.

- ^ Snider, Mike (March 13, 2012). "Are video games art? Draw your own conclusions". USA Today. Gannett. Archived from the original on June 26, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ^ Antonelli, Paola (November 29, 2012). "Video Games: 14 in the Collection, for Starters". Inside / Out. A MoMA/MoMA PS1 Blog. Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on November 30, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- ^ Orphanides, K. G. (October 28, 2015). "Explained: new US copyright exclusions for abandoned games". Wired UK. Retrieved June 17, 2023.

- ^ Cobbett, Richard (May 10, 2015). "Why it shouldn't be left to pirates to keep our games alive". TechRadar. Retrieved June 17, 2023.

- ^ a b "Emulations". Next Generation. No. 28. Imagine Media. April 1997. pp. 42–43.

- ^ "| Nintendo – Corporate Information | Legal Information (Copyrights, Emulators, ROMs, etc.)". www.nintendo.com. Archived from the original on June 18, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ Lyles, Taylor (March 4, 2024). "Yuzu Creators Will Pay Nintendo $2.4 Million in Damages and End Development of Switch Emulator". IGN. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ "Makers of Switch emulator Yuzu quickly settle with Nintendo for $2.4 million". Yahoo Finance. March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Carpenter, Nicole (March 4, 2024). "Nintendo wins $2.4M in Switch emulator lawsuit, Yuzu to shut down". Polygon. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Zwiezen, Z. (2021, August 14). Nintendo orders ROM site to 'Destroy' all its games, or else. Kotaku. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved from https://www.kotaku.com.

- ^ Valentine, Rebekah (November 12, 2018). "Nintendo reaches final judgment agreement with ROM site owners". GamesIndustry.biz. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ "Nintendo Suing Pirate Websites For Millions". Kotaku. July 23, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ a b c Lee, C. A. (2022). Video game modding in the U.S. intellectual property law: Controversial issues and gaps. Digital Law Journal, 3(4), 8-31.

- ^ "CNN - Judge rules against PlayStation emulator - April 21, 1999". www.cnn.com. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ "Court Upholds PlayStation Rival". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Coats, William; Rafter, Heather (January 1, 1993). "The Games People Play: Sega v. Accolade and the Right to Reverse Engineer Software". UC Law SF Communications and Entertainment Journal. 15 (3): 557. ISSN 1061-6578.

- ^ When Nintendo fought a device that gave Mario 'new superpowers'. (2020, November 18). CBC News. Retrieved January 19, 2023, from https://www.cbc.ca/news