Reading, Massachusetts

Reading, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

Downtown Reading in March 2014 | |

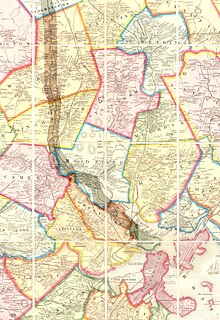

Location of Reading in Middlesex County, Massachusetts (left) and of Middlesex County in Massachusetts (right) | |

| Coordinates: 42°31′32″N 71°05′45″W / 42.52556°N 71.09583°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Middlesex |

| Settled | 1644 |

| Named for | Reading, England |

| Government | |

| • Type | Representative town meeting |

| Area | |

• Total | 9.9 sq mi (25.7 km2) |

| • Land | 9.9 sq mi (25.7 km2) |

| • Water | 0.0 sq mi (0.0 km2) |

| Elevation | 127 ft (39 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 25,518 |

| • Density | 2,600/sq mi (990/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Code | 01867 |

| Area code | 339 / 781 |

| FIPS code | 25-56130 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0618232 |

| Website | http://www.ci.reading.ma.us/ |

Reading (/ˈrɛdɪŋ/ ⓘ RED-ing) is a town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States, 16 miles (26 km) north of central Boston. The population was 25,518 at the 2020 census.[1]

History

Settlement

Many of the Massachusetts Bay Colony's original settlers arrived from England in the 1630s through the ports of Lynn and Salem.

In 1639, some citizens of Lynn petitioned the government of the colony for a "place for an inland plantation". They were initially granted six square miles, followed by an additional four. The first settlement in this grant was at first called "Lynn Village" and was located on the south shore of the "Great Pond", now known as Lake Quannapowitt. On June 10, 1644, the settlement was incorporated as the town of Reading, taking its name from the town of Reading in England.[2]

The first church was organized soon after the settlement, and the first parish separated and became the town of "South Reading" in 1812, renaming itself as Wakefield in 1868. Thomas Parker was one of the founders of Reading. He also was a founder of the 12th Congregational Church (now the First Parish Congregational Church), and served as deacon there.[3][4][5][6] He was a selectman of Reading and was appointed a judicial commissioner.[7] There is evidence that Parker was "conspicuous in naming the town" and that he was related to the Parker family of Little Norton, England, who owned land by the name of Ryddinge.[8][9][10]

A special grant in 1651 added land north of the Ipswich River to the town of Reading. In 1853 this area became the separate town of North Reading. The area which currently comprises the town of Reading was originally known as "Wood End", or "Third Parish".[2]

Reading was initially governed by an open town meeting and a board of selectmen, a situation that persisted until the 1940s. In 1693, the town meeting voted to fund public education in Reading, with grants of four pounds for three months school in the town, two pounds for the west end of the town, and one pound for those north of the Ipswich River. In 1769, the meeting house was constructed, in the area which is now the Common in Reading. A stone marker commemorates the site.[2]

Reading played an active role in the American Revolutionary War. It was prominently involved in the engagements pursuing the retreating British Army after the battles of Lexington and Concord. John Brooks, later to become Governor of Massachusetts, was captain of the "Fourth Company of Minute" and subsequently served at the Battle of White Plains and at Valley Forge. Only one Reading soldier was killed in action during the Revolution; Joshua Eaton died in the Battle of Saratoga in 1777.[2]

In 1791, sixty members started the Federal Library. This was a subscription Library with each member paying $1.00 to join, and annual dues of $.25. The town's public library was created in 1868.[2]

19th century

The Andover-Medford Turnpike was built by a private corporation in 1806-7. This road, now known as Massachusetts Route 28, provided the citizens of Reading with a better means of travel to the Boston area. In 1845, the Boston and Maine Railroad came to Reading and improved the access to Boston, and the southern markets. During the first half of the 19th century, Reading became a manufacturing town. Sylvester Harnden's furniture factory, Daniel Pratt's clock factory, and Samuel Pierce's organ pipe factory were major businesses. By the mid-19th century, Reading had thirteen establishments that manufactured chairs and cabinets. The making of shoes began as a cottage industry and expanded to large factories. Neckties were manufactured here for about ninety years. During and after Civil War the southern markets for Reading's products declined and several of its factories closed. For many years, Reading was an important casket manufacturing center.[2]

During the Civil War, members of the Richardson Light Guard of South Reading fought at the First Battle of Bull Run. A second company was formed as part of the Army of the Potomac, and a third company joined General Bank's expedition in Louisiana. A total of 411 men from Reading fought in the Civil War, of whom 15 died in action and 33 died of wounds and sickness. A memorial exists in the Laurel Hill Cemetery commemorating those who died in the Civil War.[2]

20th century

In the 20th century, Reading became a small, residential community with commuter service to Boston on the Boston and Maine Railroad and the Eastern Massachusetts Street Railway. Both commuter services were later taken over by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, and for many years, there was discussion of extending the MBTA Orange Line to Reading. Industrial expansion during that time included the Goodall-Sanford Co. off Ash Street, later sold to General Tire & Rubber Company, later known as GenCorp. Additional businesses created after World War I included the Boston Stove Foundry, Roger Reed Waxes, Ace Art, Addison-Wesley Publishing and several other companies. For many years, Wes Parker's Fried Clams was a landmark off state Route 128.

Military installations also came to the town, with two Nike missile sites, one on Bear Hill and the other off Haverhill Street, and the opening of Camp Curtis Guild, a National Guard training facility. The business community currently consists of a number of retail and service businesses in the downtown area, a series of commercial businesses in and around the former town dump on Walker's Brook Road (formerly John Street) as well as the Analytical Sciences Corporation (TASC).[2]

In 1944, Reading adopted the representative town meeting model of local government in place of the open town meeting. This retained the representative town meeting and board of selectmen, but focused policy and decision making in a smaller number of elected boards and committees whilst providing for the employment of a town manager to be responsible for day-to-day operations of the local government.[2]

Basketball player Bill Russell lived in Reading in the 1960s at 1361 Main Street, but later moved to 701 Haverhill Street.[11] Vandals broke into the basketball player's home and damaged his property, leaving racial epithets in their wake as well as defecating in Russell's bed. Russell left Reading after retiring as coach of the Boston Celtics in 1969.

In recent years the town of Reading struggled with the decisions to build a new elementary school, to cope with the influx of new families to the community, and renovate Reading Memorial High School which was opened in 1954 with an addition added in 1971. Both of these projects were approved and in August 2007 the new $57 million renovation at the High School was completed.

Geography

Reading is located at 42°31′33″N 71°6′35″W / 42.52583°N 71.10972°W (42.52585, −71.109939).[12] According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 9.9 square miles (25.7 km2). No significant amount of land is covered permanently by water, although there is a plethora of vernal pools in various areas of conservation land.

Reading borders the towns of Woburn, Stoneham, Wakefield, Lynnfield, North Reading, and Wilmington.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 3,108 | — |

| 1860 | 2,662 | −14.4% |

| 1870 | 2,664 | +0.1% |

| 1880 | 3,181 | +19.4% |

| 1890 | 4,088 | +28.5% |

| 1900 | 4,969 | +21.6% |

| 1910 | 5,818 | +17.1% |

| 1920 | 7,439 | +27.9% |

| 1930 | 9,767 | +31.3% |

| 1940 | 10,866 | +11.3% |

| 1950 | 14,006 | +28.9% |

| 1960 | 19,259 | +37.5% |

| 1970 | 22,539 | +17.0% |

| 1980 | 22,678 | +0.6% |

| 1990 | 22,539 | −0.6% |

| 2000 | 23,708 | +5.2% |

| 2010 | 24,747 | +4.4% |

| 2020 | 25,518 | +3.1% |

| 2022* | 25,205 | −1.2% |

| * = population estimate. Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23] | ||

As of the census[24] of 2010, there were 24,747 people, 9,617 households, and 6,437 families residing in the town. The population density was 2,486.1 inhabitants per square mile (959.9/km2). There were 9,617 housing units at an average density of 888.8 per square mile (343.2/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 92.4% White, 0.8% Black or African American, 0.1% Native American, 4.2% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.21% from other races, and 0.65% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.5% of the population.

There were 8,688 households, out of which 36.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 63.5% were married couples living together, 8.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 25.9% were non-families. 22.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.71 and the average family size was 3.22.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 26.3% under the age of 18, 5.1% from 18 to 24, 29.8% from 25 to 44, 24.6% from 45 to 64, and 14.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.3 males.

As of 2015, according to the Census Bureau,[25] the median income for a household in the town was $107,654 and the median income for a family was $124,485. The per capita income for the town was $47,981. Of the families in Reading, 1.0% were below the poverty line, as opposed to 1.9% of the general population. 2.7% of those under age 18 and 3.2% of those age 65 or over were under the poverty line.

Climate

In a typical year, Reading, Massachusetts temperatures fall below 50 °F (10 °C) for 195 days per year. Annual precipitation is typically 44.3 inches per year (high in the US) and snow covers the ground 62 days per year, or 17% of the year (high in the US). It may be helpful to understand the yearly precipitation by imagining nine straight days of moderate rain per year. The humidity is below 60% for approximately 25.4 days, or 7% of the year.[26]

| Climate data for Reading, Massachusetts (1990–2019 normals, extremes 1960-2019) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71 (22) |

76 (24) |

92 (33) |

94 (34) |

95 (35) |

96 (36) |

99 (37) |

105 (41) |

95 (35) |

89 (32) |

80 (27) |

78 (26) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 57 (14) |

58 (14) |

68 (20) |

83 (28) |

89 (32) |

91 (33) |

94 (34) |

91 (33) |

88 (31) |

79 (26) |

71 (22) |

61 (16) |

95 (35) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 36.1 (2.3) |

38.8 (3.8) |

46.2 (7.9) |

58.6 (14.8) |

68.4 (20.2) |

76.5 (24.7) |

82.1 (27.8) |

80.5 (26.9) |

73.1 (22.8) |

62.0 (16.7) |

51.6 (10.9) |

41.3 (5.2) |

59.5 (15.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 27.2 (−2.7) |

29.2 (−1.6) |

36.4 (2.4) |

47.6 (8.7) |

57.5 (14.2) |

66.4 (19.1) |

72.3 (22.4) |

70.8 (21.6) |

63.1 (17.3) |

52.0 (11.1) |

42.0 (5.6) |

32.8 (0.4) |

49.7 (9.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 18.4 (−7.6) |

19.7 (−6.8) |

26.7 (−2.9) |

36.5 (2.5) |

46.6 (8.1) |

56.3 (13.5) |

62.4 (16.9) |

61.2 (16.2) |

53.1 (11.7) |

41.9 (5.5) |

32.4 (0.2) |

24.3 (−4.3) |

39.9 (4.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 0 (−18) |

2 (−17) |

9 (−13) |

25 (−4) |

34 (1) |

44 (7) |

52 (11) |

50 (10) |

38 (3) |

28 (−2) |

18 (−8) |

8 (−13) |

−3 (−19) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −21 (−29) |

−15 (−26) |

−9 (−23) |

13 (−11) |

25 (−4) |

33 (1) |

41 (5) |

32 (0) |

26 (−3) |

16 (−9) |

−2 (−19) |

−14 (−26) |

−21 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.94 (100) |

3.68 (93) |

4.80 (122) |

4.34 (110) |

3.96 (101) |

4.15 (105) |

4.09 (104) |

3.91 (99) |

3.92 (100) |

4.91 (125) |

3.90 (99) |

4.82 (122) |

49.96 (1,269) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 17.1 (43) |

16.3 (41) |

13.0 (33) |

2.1 (5.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

1.9 (4.8) |

12.4 (31) |

61.7 (157) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 10 (25) |

11 (28) |

9 (23) |

1 (2.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (2.5) |

7 (18) |

16 (41) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 12 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 137 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 8 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 28 |

| Source: NOAA[27] | |||||||||||||

Government

Since 1944, the municipal government of the town of Reading comprises a representative town meeting, whose 192 members are elected from eight precincts.[28][29][30] Prior to 1944, the town was governed by an open town meeting.

The town elects a five-member select board by general election, who serve for overlapping three-year terms. The select board are responsible for calling the elections for the town meeting, and for calling town meetings. They initiate legislative policy by proposing legislative changes to the town meeting, and then implement the votes subsequently adopted. They also review fiscal guidelines for the annual operating budget and capital improvements program and make recommendations on these to the town meeting. In addition the board serves as the local road commissioners and licensing board, and appoints members to most of the town's other boards, committees, and commissions.[31]

The day-to-day running of the town government is the responsibility of a town manager, appointed by the board of selectmen.[31]

Transportation

Reading is located close to the junction of Interstate 93 and Interstate 95/Massachusetts Route 128 to the north of Boston. I-93 provides a direct route south to central Boston and beyond via the Big Dig, whilst I-95/128 loops around Boston to the west, crosses Interstate 90/Massachusetts Turnpike, and then continues south before meeting up with I-93 again at Canton.

Reading is served by Reading station on the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority's Haverhill/Reading commuter rail line, which links the town to Boston's North Station. Plans existed during the 1970s, when this line of track was bought by the MBTA, to extend the Orange Line rapid transit service out as far as Reading. Although new stations were successfully constructed at Malden Center and Oak Grove station, residents just past Oak Grove complained and such plans were put on hold.

Reading is also served by MBTA bus service routes 136 and 137, which run between Reading station and Malden station.

Education

Reading's public school system, managed by Reading Public Schools, comprises:[32]

- Reading Memorial High School

- Coolidge Middle School

- Walter S. Parker Middle School

- A. M. Barrows Elementary School

- Birch Meadow Elementary School

- Joshua Eaton Elementary School

- JW Killam Elementary School

- Wood End Elementary School

Austin Preparatory School, is a co-ed, independent school, in the Augustinian Catholic tradition, founded in 1962. It is located on 55 acres of land and has an enrollment of 700 students, providing instruction for students in grades 6–12.

Points of interest

- The Parker Tavern – The town's oldest remaining 17th century structure, built in 1694. This property, on Washington Street, is currently owned and operated by the non-profit Reading Antiquarian Society.[2]

- The roof of the St. Athanasius Parish, on Haverhill St., was designed by Louis A. Scibelli and Daniel F. Tulley, and is one of the largest hyperbolic paraboloids in the Western Hemisphere. The roof was a point of great interest. The pouring of the concrete roof had to be done in one day.

- Burbank Arena skating rink on Haverhill St. as well as private condos on Bear Hill St. both reside over the sites of decommissioned Army National Guard Nike Ajax missile silos.[33][34]

- The Stephen Hall House, a building on the National Register of Historic Places.

- The Capt. Nathaniel Parker Red House, a building on the National Register of Historic Places, known for its Red exterior. It was the original town Tavern, and a meeting place for notable American Revolutionaries.

- The Walnut Street School, a building on the National Register of Historic Places, and current home to a local community theatre.

Local media

- The Daily Times Chronicle publishes a Reading edition of the newspaper on weekdays.[35]

- The Reading Advocate publishes weekly and is delivered by mail.[36]

- Reading's Community Access Television station is RCTV, which provides trainings and air-time for residents to produce their own programs.[37]

Notable people

- Jess Brallier, award-winning publisher, best-selling author, and web publisher

- James Cerretani, pro tennis player and ranked No. 50 in the world in doubles play

- Clarence DeMar, seven-time winner of the Boston Marathon, died in Reading, June 11, 1958

- John Doherty, Major League Baseball player for parts of two seasons for the California Angels

- Mark Erelli, folk musician

- William M. Fowler, U.S. naval historian, professor at Northeastern University and former director of the Massachusetts Historical Society

- Fred Foy, radio and television announcer for the Lone Ranger, Green Hornet, Sgt. Preston of the Yukon, and Dick Cavett shows

- John Hart, originally from Ipswich (born October 13, 1751); served as a regimental surgeon during the American Revolution

- Thomas Junta, hockey dad convicted of involuntary manslaughter

- Danny McBride, lead guitarist for Sha Na Na, a member of the RMHS class of '63

- Lennie Merullo, professional baseball player who played for the Chicago Cubs for seven seasons and became a professional baseball scout until the age of 85

- Moses Nichols, officer during the American Revolutionary War

- Thomas Parker, founder of Reading

- Eddie Peabody, banjo player

- Chris Pizzotti, former Harvard University and New York Jets quarterback

- Bill Russell, former member of the Boston Celtics from 1956 to 1969

- Matt Siegel, WXKX-FM disc jockey once lived on the West Side

- Tom Silva, general contractor for This Old House on PBS

- Cousin Stizz, rapper, made songs with Migos and has his song "Butterfly" in NBA 2k20

- Charles Stuart, murderer

- Mollie Sweetser, American politician

- Jonathan Temple (1796–1866), Los Angeles, California, landowner, cattle rancher and politician, born in Reading

- William Weston, Vermont politician who served as a member of the Vermont Senate, born in Reading[38]

- Brad Whitford, guitarist for Aerosmith, a member of the RMHS class of '70

See also

References

- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Reading town, Middlesex County, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "The Town of Reading – History". The Town of Reading. Archived from the original on March 18, 2019. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ Our History. First Parish Congregational Church. fpccwakefield.com

- ^ Parker, Theodore, John Parker of Lexington and his Descendants, Showing his Earlier Ancestry in America from Dea. Thomas Parker of Reading, Mass. from 1635 to 1893, pp. 15–16, 468–470, Press of Charles Hamilton, Worcester, MA, 1893.

- ^ About Wakefield. wakefield.ma.us

- ^ Eaton, William E. Historical Sketches of Ancient Redding, Massachusetts, Vol. I, pp. 6, 6A, 20, 23, 30, 34, 114–5, Wakefield, MA, 1935.

- ^ Cutter, William Richard, Historic Homes and Places and Genealogical and Personal Memoirs Relating to the Families of Middlesex County, Massachusetts, p. 1860, Lewis Historical Publishing Co., New York, NY, 1908.

- ^ Parker, Theodore, John Parker of Lexington and his Descendants, Showing his Earlier Ancestry in America from Dea. Thomas Parker of Reading, Mass. from 1635 to 1893, pp. 21–36, Press of Charles Hamilton, Worcester, MA, 1893.

- ^ Parker, Augustus G., Parker in America, 1630–1910, pp. 5, 27, 49, 53–54, 154, Niagara Frontier Publishing Co., Buffalo, NY, 1911.

- ^ A Brief History Archived October 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. wakefieldhistory.org

- ^ Goudsouzian, Aram. King of the Court: Bill Russell and the Basketball Revolution. Univ of California Press, 2011.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "City and Town Population Totals: 2020−2022". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- ^ "Climate in Reading, Massachusetts". Retrieved September 3, 2022.

- ^ "Climate". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

- ^ 1943 Chap. 0007. An Act Establishing In The Town Of Reading Representative Town Government By Limited Town Meetings. Boston, Massachusetts: Secretary of the Commonwealth. 1943.

- ^ "The Town of Reading – Voting Precincts". The Town of Reading. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ^ "Town of Reading". MMA.org. Massachusetts Municipal Association. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ a b "The Town of Reading – Board of Selectmen". The Town of Reading. Archived from the original on December 24, 2012. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ^ "Directory List". Reading Public Schools. Retrieved November 8, 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Missile Sites. Ed-thelen.org. Retrieved on July 21, 2013.

- ^ Nike Sites of Boston: Reading B-03 CL. Ed-thelen.org (May 17, 2000). Retrieved on July 21, 2013.

- ^ "Reading Chronicle". Woburn Chronicle. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ^ "Reading Advocate". WickedLocal.com. Gatehouse Media. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ^ "Reading Community Television". RCTV.org. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ^ "The Late William Weston". Burlington Free Press. Burlington, VT. April 2, 1875. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

Further reading

- Dutton, E.P. Chart of Boston Harbor and Massachusetts Bay with Map of Adjacent Country. Published 1861. A good map of roads and rail lines from Reading to Boston and surrounding area.

- History of the Town of Reading, including the Present Towns of Wakefield, Reading and North Reading with Chronological and Historical Sketches from 1639 to 1874. By Lilley Eaton, 815 pages, published 1874.

- History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts, by Samuel Adam Drake, published 1880, Volume 2. Page 270 Reading by Hirum Barrus and Carroll D. Wright. Page 259 North Reading. Page 399 Wakefield by Chester W. Eaton.