Portal:Phoenicia

THE PHOENICIA PORTAL

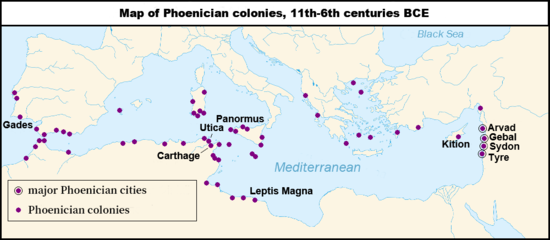

Phoenicia (/fəˈnɪʃə, fəˈniːʃə/), or Phœnicia, was an ancient Semitic thalassocratic civilization originating in the coastal strip of the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenicians expanded and contracted throughout history, with the core of their culture stretching from Arwad in modern Syria to Mount Carmel in modern Israel covering the entire coast of modern Lebanon. Beyond their homeland, the Phoenicians extended through trade and colonization throughout the Mediterranean, from Cyprus to the Iberian Peninsula.

The Phoenicians directly succeeded the Bronze Age Canaanites, continuing their cultural traditions following the decline of most major cultures in the Late Bronze Age collapse and into the Iron Age without interruption. It is believed that they self-identified as Canaanites and referred to their land as Canaan, indicating a continuous cultural and geographical association. The name Phoenicia is an ancient Greek exonym that did not correspond precisely to a cohesive culture or society as it would have been understood natively. Therefore, the division between Canaanites and Phoenicians around 1200 BC is regarded as a modern and artificial division.

The Phoenicians, known for their prowess in trade, seafaring and navigation, dominated commerce across classical antiquity and developed an expansive maritime trade network lasting over a millennium. This network facilitated cultural exchanges among major cradles of civilization like Greece, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. The Phoenicians established colonies and trading posts across the Mediterranean; Carthage, a settlement in northwest Africa, became a major civilization in its own right in the seventh century BC.

The Phoenicians were organized in city-states, similar to those of ancient Greece, of which the most notable were Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos. Each city-state was politically independent, and there is no evidence the Phoenicians viewed themselves as a single nationality. While most city-states were governed by some form of kingship, merchant families likely exercised influence through oligarchies. After reaching its zenith in the ninth century BC, the Phoenician civilization in the eastern Mediterranean gradually declined due to external influences and conquests. Yet, their presence persisted in the central and western Mediterranean until the destruction of Carthage in the mid-second century BC. — Read more about Phoenicia, its mythology and language

Featured article

•

Featured article

•

A Featured article represents some of the best content on Wikipedia

The Battle of Bagradas, the Bagradas, or the Bagradas River (the ancient name of the Medjerda) may refer to:

- Battle of the Bagradas River (255 BC), also known as the Battle of Tunis, during the First Punic War

- Battle of the Bagradas River (240 BC), also known as the Battle of the Macar, during the Mercenary War

- Battle of the Bagradas River (203 BC), usually known as the Battle of the Great Plains, during the Second Punic War

- Battle of the Bagradas River (49 BC), a battle during the Roman civil war between Caesar and Pompey

- Battle of the Bagradas River (536), a battle between the rebel leader Stotzas and Byzantine commander Belisarius (Full article...)

List of Featured articles

|

|---|

Phoenician mythology •

Images

-

Phoenician sarcophagi found in Cádiz, Spain, thought to have been imported from the Phoenician homeland around Sidon. Archaeological Museum of Cádiz. (from Phoenicia)

-

Ruins of the Punic and then Roman town of Tharros (from Punic people)

-

Major Phoenician trade networks (c. 1200–800 BC) (from Phoenicia)

-

Earring from a pair, each with four relief faces; late fourth–3rd century BC; gold; overall: 3.5 x 0.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (from Phoenicia)

-

Phoenician metal bowl with hunting scene (8th century BC). The clothing and hairstyle of the figures are Egyptian. At the same time, the subject matter of the central scene conforms with the Mesopotamian theme of combat between man and beast. Phoenician artisans frequently adapted the styles of neighboring cultures. (from Phoenicia)

-

Female figurines from Tyre (c.1000–550 BC). National Museum of Beirut. (from Phoenicia)

-

Carthaginian sphere of influence 264 BC (from Punic people)

-

Phoenicians build pontoon bridges for Xerxes I of Persia during the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC (1915 drawing by A. C. Weatherstone). (from Phoenicia)

-

Face bead; mid-4th–3rd century BC; glass; height: 2.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (from Phoenicia)

-

Map of Phoenician (yellow labels) and Greek (red labels) colonies around 8th to 6th century BC (with German legend) (from Phoenicia)

-

Figure of Ba'al with raised arm, 14th–12th century BC, found at ancient Ugarit (Ras Shamra site), a city at the far north of the Phoenician coast. Musée du Louvre (from Phoenicia)

-

Tomb of King Hiram I of Tyre, located in the village of Hanaouay in southern Lebanon. (from Phoenicia)

-

Oinochoe; 800–700 BC; terracotta; height: 24.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) (from Phoenicia)

-

19th-century depiction of Phoenician sailors and merchants. The importance of trade to the Phoenician economy led to a gradual sharing of power between the King and assemblies of merchant families. (from Phoenicia)

-

Achaemenid-era coin of Abdashtart I of Sidon, who is seen at the back of the chariot, behind the Persian King. (from Phoenicia)

-

Sarcophagus of Ahiram, which bears the oldest inscription of the Phoenician alphabet. National Museum of Beirut (from Phoenicia)

-

Phoenician faces. Glass from Olbia, 4th century BC. The bold pools of color and detailed hair give a Greek impression. (from Phoenicia)

-

A naval action during Alexander the Great's Siege of Tyre (332 BC). Drawing by André Castaigne, 1888–89. (from Phoenicia)

Good article

•

Good article

•

A Good article meets a core set of high editorial standards

The Battle of Salamis (/ˈsæləmɪs/ sal-ə-MISS) was a naval battle fought in 480 BC, between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles, and the Achaemenid Empire under King Xerxes. It resulted in a decisive victory for the outnumbered Greeks. The battle was fought in the straits between the mainland and Salamis, an island in the Saronic Gulf near Athens, and marked the high point of the second Persian invasion of Greece. It was arguably the largest naval battle of the ancient world, and marked a turning point in the invasion.

To block the Persian advance, a small force of Greeks blocked the pass of Thermopylae, while an Athenian-dominated allied navy engaged the Persian fleet in the nearby straits of Artemisium. In the resulting Battle of Thermopylae, the rearguard of the Greek force was annihilated, while in the Battle of Artemisium the Greeks suffered heavy losses and retreated after the loss at Thermopylae. This allowed the Persians to conquer Phocis, Boeotia, Attica and Euboea. The allies prepared to defend the Isthmus of Corinth while the fleet was withdrawn to nearby Salamis Island. (Full article...)Phoenician inscriptions & language •

The Baal Lebanon inscription, known as KAI 31, is a Phoenician inscription found in Limassol, Cyprus in eight bronze fragments in the 1870s. At the time of their discovery, they were considered to be the second most important finds in Semitic palaeography after the Mesha stele.

It was purchased in 1874–75 by a Limassol merchant named Laniti from a scrap metal dealer, who did not know of their previous provenance. A copy was passed to Julius Euting, and after Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau secured its acquisition by the Cabinet des Médailles, the inscription was published in full by Ernest Renan in 1877.

It is particularly notable for having mentioned Hiram I. It is the only Phoenician inscription to suggest a "colonial" system amongst the Phoenician domains. (Full article...)Did you know (auto-generated) •

- ... that the earliest-known Phoenician inscriptions were found near Bethlehem?

- ... that the deity of the Phoenician sanctuary of Kharayeb remains unidentified due to the absence of names of specific gods in unearthed inscriptions?

- ... that the sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II, the Phoenician king of Sidon, is one of only three ancient Egyptian sarcophagi unearthed outside Egypt?

- ... that Eshmunazar I, the Phoenician king of Sidon, participated in the Neo-Babylonian campaigns against Egypt, where he seized stone sarcophagi belonging to members of the Egyptian elite?

- ... that alongside a 7th-century BC Phoenician shipwreck, two additional wrecks from various historical periods were unearthed in Bajo de la Campana, situated off the coast of Cartagena, Spain?

- ... that according to second-century AD Greek rhetorician Athenaeus, the Phoenicians played a flute-like instrument called the gingras in their mourning rituals?

Related portals

Categories

Wikiproject

Other Wikimedia and Wikiportals

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wikivoyage

Free travel guide -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus

Parent portal: Lebanon