Perry Como television and radio shows

Perry Como was an American singer, radio and television performer whose career covered more than fifty years. He is probably best known for his television shows and specials over a period of almost thirty years.[1][2] Como came to television in 1948 when his radio show was selected by NBC for experimental television broadcasts.[3] His television programs were seen in more than a dozen countries, making Como a familiar presence outside of the United States and Canada.[4][5][6]

He received five Emmys from 1955 to 1959,[7] a Christopher Award (1956) and shared a Peabody Award with good friend Jackie Gleason in the same year.[8][9] Como was inducted into the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Hall of Fame in 1990[10][11][12] and received a Kennedy Center Honor in 1987.[13] Como has the distinction of having three stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for his work in radio, television, and music.[14]

Radio

Perry Como began performing on radio in 1936 when he became a member of the Ted Weems Orchestra. The band had its own weekly radio show on the Mutual Broadcasting System from 1936 to 1937.[15][16] They were also part of the regularly featured cast of Fibber McGee and Molly.[17][18][19][20] Ted Weems and his Orchestra were cast members for the first season of the radio show Beat the Band, which was a musical quiz show; they were weekly performers from 1940 – 1941.[15] Como left the Ted Weems Orchestra for his home in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania with the intention of returning to his trade as a barber in late 1942. Before he could sign a lease for a barber shop, Como was offered an opportunity to host his own sustaining (non-sponsored) radio show on CBS from New York City.[10][21][22] He began working for CBS March 12, 1943.[23]

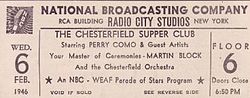

Doug Storer, then an advertising executive with the Blackman Company, was a listener of Como's CBS radio show. Storer believed Como's ability and style would be ideal for a new radio variety program he was planning. He created an audition recording of the proposed program with Como and the Mitchell Ayres Orchestra and brought it to the advertising agency that handled the Chesterfield cigarettes account. The agency liked the concept of the radio show, but had someone else in mind as its host. The singer of their choice was under contract with someone else, so the agency asked Storer to obtain a release from his contract for their new program. Storer believed that Perry Como was the right host for the new radio show and did not do anything about the singer's release from his contract. Weeks later, he received a call from Chesterfield's advertising agency, asking about the status of the singer's contract, since the show was scheduled to begin on NBC in about one week. Storer told the agency that the right person for their new program was the man on the audition recording. The agency had no time to spare and agreed to sign Perry Como.[24] At the end of 1944, Como became the host of The Chesterfield Supper Club.[25][26][27]

The Chesterfield Supper Club had a main theme song, "Smoke Dreams", composed by John Klenner, Lloyd Shaffer and Ted Steele. Another musical theme that was also used on the broadcasts was Roy Ringwald's "A Cigarette, Sweet Music and You".[28] These themes were also used when the Chesterfield Supper Club television shows began in 1948.[3] Como was joined by Jo Stafford in 1946, with Perry hosting the 15 minute program on Monday, Wednesday and Friday evenings. By 1948, Peggy Lee and the Fontane Sisters had joined the cast, with the Fontane Sisters moving to television with Como.[29][26][30][31] The radio show continued and was simulcast after the "Supper Club" television broadcasts began; Como was heard on radio until he left NBC in 1950 for CBS with The Perry Como Chesterfield Show.[3] Mutual began simulcasting his CBS television show on radio in 1953; it was the first instance of a simulcast between two different networks.[10] The radio show continued until June 1955, when Como left CBS to return to NBC.[10][32][33] [34][35][36]

Radio shows

|

As host or cast member

|

As a guest

|

Television

Como's television career began when NBC decided to experiment with televising his Chesterfield Supper Club radio show on December 24, 1948. The cameras were simply brought into the radio studio to televise the radio broadcast of the show.[3][40][41] NBC initially planned to televise three Friday evening "Supper Club" radio shows; the network was pleased enough with the results that the experimental period was extended into August 1949.[42][43] Como admitted that he felt awkward and unsure at first, but was able to relax enough to perform on the television show in the same manner as he did for normal radio broadcasts.[44] On September 8, 1949, Chesterfield Supper Club became an officially scheduled television program airing on Sunday nights for a half-hour.[27][45]

Perry and his sponsor moved to CBS in 1950; the show was re-titled The Perry Como Chesterfield Show and the schedule returned to one similar to the "Supper Club" radio shows: a 15-minute program three times a week.[10][46][47] J. Fred Muggs, who rose to fame on the NBC Today show, made his debut on Perry Como's CBS program. Pat Weaver of Today saw the baby chimp on the show and thought he would be able to help his still-floundering morning program.[48] NBC offered Como a long-term contract to host a weekly hour-long television show that would beginning in the fall of 1955. Como signed a 12-year contract with the network in April 1955.[32]

The Perry Como Show made its debut September 17, 1955, with the following announcement from announcer Frank Gallop: "We assume everyone can read, so we will not shout at you."[49] Initially, only Gallop's voice was heard because there was not enough room for him to appear onstage.[50][51] Clad in his well-known cardigan sweaters, Como welcomed guest stars to his musical-comedy variety program.[3][52][53] The "Sing to me, Mr. C." segment of the show was where Como responded to letters of viewer song requests.[6][54][55] Como was seated on a stool as he sang some of the music of the weekly requests. The setting for this segment had its beginnings in the first television broadcasts of the Chesterfield Supper Club. Como and his guests did the radio show sitting on stools behind music stands; this is what was seen by the cameras when they initially came into the radio studio.[56] The opening theme song for Como's shows from 1955 to 1963 was "Dream Along with Me (I'm On My Way to a Star)".[3] The closing theme was "You Are Never Far Away From Me". "We Get Letters", composed by Ray Charles, was the musical beginning of the "Sing to me, Mr. C." segment of Como's weekly shows. It was revived by the Late Show with David Letterman.[57]

The Perry Como Show was rated as number seven in the Nielsen top ten after it had been on the air for two months.[58] The program became one of the first color television programs with its 1956 season premiere; it was also the only NBC television show in the Nielsen top ten for the 1956–1957 season.[10][59] During this time, a ratings war developed between the Como show and that of entertainer Jackie Gleason. Off-screen, Gleason and Como were long-time friends; Como had been one of those who filled in for Gleason in 1954, when he suffered a broken leg and ankle in an on-air fall.[60][61] While both men were eager to win, neither wanted to do so at all costs. They kept their friendship intact with phone calls the day after the show; the winner of the weekly ratings battle phoned the loser for some good-natured joking.[10][62]

Kraft Foods had been the sponsor of a long-running radio program called Kraft Music Hall. The company decided to develop the show for television in 1958, hosted by Milton Berle.[63] Kraft approached Perry Como regarding becoming the program's new host in early 1959. Como signed what was then a record-breaking deal with Kraft, receiving $25 million to host the show for the next two years with another contract to serve as the company's spokesman for the next seven years. The agreement also put Como in charge of his television show's production, as well as for the shows replacing it during the summer hiatus. Como's production company, Roncom, named for his son, Ronnie Como, handled the transactions.[64] Como also had control of the show which would replace his during the summer television hiatus.[65][66] Como then moved from Saturday evenings to Wednesday evenings with Perry Como's Kraft Music Hall.

Como, who had done a regularly scheduled television show since 1948, began taking a slower pace by the fall of 1963. From 1963 to 1967, he only appeared on television in seven specials per season. The Como show was rotated with three other Kraft-sponsored programs: Kraft Suspense Theatre, The Andy Williams Show, and The Road West. After 1967, his television appearances mainly came in the form of specials at holidays, especially Christmas.[3][67][68][69] Como actually began doing specials in 1960 while he was still hosting Kraft Music Hall. Perry Como Comes To London was the first of these programs which would eventually span over twenty-five years.[70] He continued with the television specials, which were filmed in countries like Austria, France, Mexico and the United States until 1987, when an angry Como canceled the Christmas special after being offered a 10 pm late-prime time slot, outside the family hour, by ABC.[71] Como's final Christmas special, Perry Como's Irish Christmas, was seen on PBS in 1994.[10][72]

Television shows

Regularly scheduled television shows

- The Perry Como Chesterfield Supper Club (1948–1950).[45]

- The Perry Como Chesterfield Show (1950–1955)[73]

- The Perry Como Show (1955–1959)[74]

- Perry Como's Kraft Music Hall (1959–1967)[74]

Television specials

- Perry Como Comes To London (1960)[70]

- The Perry Como Holiday Special (1967)[75]

- Perry Como Special - In Hollywood (1968)

- Academy of Professional Sports Awards (February 21, 1969)[76]

- Christmas At The Hollywood Palace (1969)[10]

- The Many Moods Of Perry Como (1970)[77]

- Perry Como - In Person (1971)

- Perry Como's Winter Show (1971)[78]

- The Perry Como Winter Show (1972)[79]

- Cole Porter in Paris (1973)[80]

- The Perry Como Winter Show (1973)[81]

- The Perry Como Sunshine Show (1974)[82]

- Perry Como's Summer of '74 (1974)[82]

- Perry Como's Christmas Show (1974)[82]

- Como Country: Perry And His Nashville Friends (1975)[83]

- Perry Como's Springtime Special (1975)[82]

- Perry Como's Lake Tahoe Holiday (1975)[82]

- Perry Como's Christmas in Mexico (1975)[82]

- Perry Como's Hawaiian Holiday (1976)[82]

- Perry Como's Spring in New Orleans (1976)[82]

- Perry Como: Las Vegas Style (1976)[82]

- Perry Como's Christmas in Austria (1976)[82]

- Perry Como's Music From Hollywood (1977)[82]

- Perry Como's Olde Englishe Christmas (1977)[82]

- Perry Como's Easter by the Sea (1978)[82]

- Perry Como's Early American Christmas (1978)[84]

- Perry Como's Springtime Special (1979)[82]

- Perry Como's Christmas in New Mexico (1979)[82]

- Perry Como's Bahamas Holiday (1980)[82]

- Perry Como's Christmas in the Holy Land (1980)[82]

- Perry Como's Spring in San Francisco (1981)[82]

- Perry Como's French-Canadian Christmas (1981)[82]

- Perry Como's Easter in Guadalajara (1982)[82]

- Perry Como's Christmas in Paris (1982) [82]

- Perry Como's Christmas in New York (1983)[82]

- Perry Como's Christmas in England (1984)[82]

- Perry Como's Christmas in Hawaii (1985)[85]

- The Perry Como Christmas Special (1986)[86]

- Perry Como in Japan (March 1993-Japanese TV)[10]

- Perry Como's Irish Christmas (1994)[87]

Guest appearances

- The Frank Sinatra Show (March 10, 1951)[10]

- Texaco Star Theater (December 27, 1949), (January 9, 1951),

(January 16, 1951)[10] - Arthur Godfrey and His Friends (March 29, 1950), (April 5, 1950)[10]

- Treasury Open House (June 2, 1950)[10]

- The Frank Sinatra Show (October 19, 1951)[10]

- The U. S. Royal Showcase (February 23, 1952)[10]

- New York Hospital Cardiac Telethon (March 14/15, 1952)[10]

- Strike It Rich (December 17, 1952) [10]

- The Stork Club (January 10, 1953) [10]

- Stars on Parade (military-1953-1954-date unk.)[3]

- The All-Star Revue (February 14, 1953)[10]

- Colgate Comedy Hour (December 13, 1953)[10]

- Rosalia Home Fund Telethon (April 24, 1954 WDTV, Pittsburgh)[88]

- Dateline (December 13, 1954)[10][74]

- Max Leibman's Variety (January 30, 1955)[74]

- Some Of Manie's Friends: Tribute To RCA/NBC Executive Manie Saks (March 3, 1959)[74]

- The Bob Hope Show (November 18, 1956)[74]

- The Dinah Shore Chevy Show (January 31, 1957)[10]

- Il Musichiere (September 14, 1958)[10]

- Pontiac Star Special (March 24, 1959) [89]

- The Bing Crosby Show (February 28, 1960)[67]

- Bob Hope Special ~ "Potomac Madness" (October 21, 1960)[90]

- Celebrity Golf (October 9, 1960)[10]

- The Bob Hope Show (November 8, 1967)[10]

- Ethel Kennedy's Telethon (February 11, 1968) [10]

- Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In (November 25, 1968)[10]

- The Carol Burnett Show (January 20, 1969)[91]

- Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In (January 13, 1969)[10]

- Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In (March 24, 1969)[10]

- Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In (February 16, 1970)[10]

- Jimmy Durante Presents the Lennon Sisters (March 28, 1970)[10]

- The Tom Jones Show (November 6, 1970)[92]

- Evening at Pops (August 14, 1970) [10][74]

- The Doris Mary Anne Kapplehoff Special ~ The Doris Day Special (March 14, 1971)[93]

- The Pearl Bailey Show (December 26, 1971) [10]

- The Flip Wilson Show (October 6, 1971)[94]

- Julie on Sesame Street (November 23, 1973)[74]

- The Royal Variety Performance (November 24, 1974)[74]

- The Barber Comes To Town (December 14, 1975-BBC)[10]

- Ann-Margret: Rhinestone Cowgirl (April 26, 1977)[74]

- Parkinson (November 26, 1977) (UK)[10]

- Christmas With Nationwide: Journey to Bethlehem (December 21, 1977-BBC)[10]

- Bob Hope's Christmas Show (December 19, 1977)[10][74]

- Entertainment Tonight ~ On Perry Como's 40th Anniversary With RCA Records (1983)

- Today (July 5, 6, 7, 1983) [10]

- Bob Hope's Salute to NASA: 25 Years of Reaching for the Stars (July 5, 1983)[10][74]

- Emmy Awards (September 25, 1983)[10]

- The Kennedy Center Honors (December 27, 1983)[10]

- The Arlene Herson Show (June 6, 1984)[10]

- Good Company (Minneapolis TV Interview) (June 19, 1984)[10]

- AM Cleveland (July 31, 1984))[10]

- Regis Philbin's Life Styles (August, 1984)[10]

- Duke Children's Classic (May 1986-ESPN)[10]

- The Kennedy Center Honors (December 6, 1987)[74]

- Val Doonican's Very Special Christmas (December 24, 1987-BBC)[10]

- Evening at Pops—"A Tribute to Bing Crosby" (August 20, 1988)[74]

- Live with Regis & Kathie Lee (December 12, 1988)[10]

- Duke Children's Classic (May 15, 1989-ESPN)[10]

- Live with Regis & Kathie Lee (July 7, 1989)[10]

- Gala Concert For President Ronald Reagan (October 22, 1989)[10]

- The 6th Annual Television Academy of Arts and Sciences Hall of Fame

(January 24, 1990)[10][74] - Sinatra 75: The Best is Yet to Come (Frank Sinatra 75th Birthday Celebration) (1990)[74]

- Night of 100 Stars III (1990)[74]

- Broadcast Hall of Fame (January 7, 1990)[10]

- Sammy Davis Jr. Variety Club Telethon (KMOV-St. Louis) (March 2–3, 1990)[10]

- Live with Regis & Kathie Lee (December 4, 1990)[10]

- Live with Regis & Kathie Lee (December 5, 1990)[10]

- Hard Copy ~ Perry Como - The King of Crooners (June 14, 1991)[10]

- CBS This Morning (December 20, 1991)[10]

- National Memorial Day Concert, Washington D.C. (May 22, 1992)[74]

- Kenny Live (January 15, 1994-RTÉ)[10]

- Sammy Davis Jr. Variety Club Telethon (KMOV-St. Louis) (March 5–6, 1994)[10]

- Live with Regis & Kathie Lee (November 15, 1994)[10]

- Duke Children's Classic (May 1995)[10]

Filmography

Perry Como was signed to a seven-year 20th Century-Fox contract in 1943, prior to his becoming the host of the Chesterfield Supper Club.[95] Como wound up in a stock company, where actors were called for work only if the studio needed to make a film to complete a schedule.[96] For the filming of Something for the Boys in 1944, Como was told to report immediately to the Fox Studio Hollywood lot. It was five weeks from Como's arrival to his being called onto the set. When he came on the movie set, the director did not know who he was.[96]

Como made five feature films, but felt that his roles and his personality were a poor match. He expressed his discomfort with the medium, saying in 1949, "Television is going to do me a lot more personal good than the movies ever have...The reason should be obvious. On television, I'm allowed to be myself; in pictures, I was always some other guy. I come over like just another bum in a tuxedo."[42] Though his last movie, Words and Music, was produced by prestigious Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the change was of little help. Shortly before the film's debut, columnist Walter Winchell reported the following in his column: "Someone at MGM must have been dozing when they wrote the script for Words and Music. In most of the film Perry Como is called Eddie Anders and toward the end (for no reason) they start calling him Perry Como."[97] Como then asked for and received a release from the remainder of his MGM contract, saying, "I was wasting their time and they were wasting mine.".[38][98][99][100]

Films

Including shorts

- Swing, Sister, Swing (1938) with the Ted Weems Orchestra[101]

- Swing Frolic (1942) with the Ted Weems Orchestra[102]

- Upbeat in Music (1943)

- Something for the Boys (1944)

- Doll Face (1945) [103][104][105]

- March of Time (1945)

- If I'm Lucky (1946)

- Words and Music (1948)

- Tobaccoland on Parade (1950)

- The Fifth Freedom (1951).[10]

See also

- Perry Como discography

- Perry Como albums

- List of songs recorded by Perry Como

- Best selling music artists

- List of popular music performers

References

- ^ Laffler, William D. (21 August 1983). "Chopin Tune Helped Bring Fame to Perry Como". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ Campbell, Mary (11 June 1983). "Fifty years in show business". Rome News Tribune. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brooks, Tim; Marsh, Earle F., eds. (1987), The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows, Ballantine Books, pp. 1071–1072, ISBN 0-345-49773-2, retrieved 14 April 2010

- ^ Bacon, James (8 November 1960). "Como's Best Liked of Shows Abroad". Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ O'Brian, Jack (1 July 1971). "Como Far From Retired But He Fishes A Lot". Sarasota Journal. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ^ a b Severo, Richard (13 May 2001). "Perry Como, Relaxed and Elegant Troubadour of Recordings and TV, Dies at 88". New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "Primetime Emmy Database". American Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ Moore, Jacqueline (5 January 1957). "Perry Como: Even His Rivals Are Fans (pages-40,41,53)". Ottawa Citizen Magazine. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ "Como, Gleason Win Peabody Award". Long Beach Independent. April 12, 1956. p. 32. Retrieved January 5, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm Macfarlane, Malcolm, ed. (2009), Perry Como: A Biography and Complete Career Record, McFarland, p. 310, ISBN 978-0-7864-3701-6, retrieved 28 April 2010

- ^ "Como inducted into TV Hall of Fame tonight". Observer-Reporter. 24 January 1990. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ^ "Hall of Fame Lists Inductees". Spartanburg Herald-Journal. 12 December 1989. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ "Kennedy Center Honorees-Perry Como". 1987. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "Perry Como Hollywood Star Walk". LA Times. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dunning, John, ed. (1998), On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio, Oxford University Press, USA, p. 75, ISBN 0-19-507678-8, retrieved 7 April 2010

- ^ Cochran, Marie (26 March 1937). "Mr. Weems' Mr. Gibbs Comes Home, Tells All". The Toledo News-Bee. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ "Perry Como Biography". Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ "Ted Weems and his Orchestra". RedHot Jazz.com. Archived from the original on 25 January 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ a b audio file of Perry Como with Ted Weems Orchestra singing "Cabin of Dreams" on the "Fibber McGee & Molly" show on NBC October 11, 1937 (RealPlayer)

- ^ Monday Night Comes To Life. Life. 12 April 1937. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- ^ "Perry Como Gets More 'Swoons' Than Anyone". St. Petersburg Times. 25 July 1943. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ "Perry Como Started Out To Be Barber". Herald-Journal. 28 October 1951. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- ^ a b Cohen, Harold V. (5 March 1943). "The Drama Desk". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ Storer, Doug (14 October 1983). "Doing it his way paid off for famous trio". The Evening Independent. Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- ^ Mackenzie, Harry, ed. (1999), The Directory of the Armed Forces Radio Service Series, Greenwood Press, pp. 87–88, ISBN 0-313-30812-8, retrieved 14 April 2010

- ^ a b Fleming, Robert (23 November 1947). "Crosby Takes It Easy, But So Does Perry Como". Milwaukee Journal.

- ^ a b "Two Gypsy Folk Tales". Ottawa Citizen. 8 August 1949. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "The Chesterfield Supper Club". classicthemes.com. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ "Fontane Sisters Spend Yule with Parents in Cornwall". The Newburgh News. 26 December 1951. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ^ "Actresses and Vocalists Star on Networks". Youngstown Vindicator. 9 December 1945. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ^ Dunning, John, ed. (1998). On the air: the encyclopedia of old time radio. Oxford University Press USA. p. 840. ISBN 0-19-507678-8. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ a b Baft, Atra (1 April 1955). "Perry Como Signs With NBC For One-Hour Show Weekly". Reading Eagle. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ O'Brian, Jack (30 June 1955). "Value of $350,000 Is Placed On Farewell Gift to Como". Reading Eagle. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Perry Como Obituary". CNN. 13 May 2001. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Carnes, Mark C., ed. (2005). American national biography:Supplement issue 2. Oxford University Press USA. p. 848. ISBN 0-19-522202-4. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ "A gift to the community, A Perry Como Christmas Special". TCPalm. 20 December 2010. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ a b "A Bing Crosby Discography, part 2d - Radio Chesterfield Cigarettes, 21 September 1949-25 June 1952". jazzdiscography.com. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

- ^ a b Gilliland, John (1994). Pop Chronicles the 40s: The Lively Story of Pop Music in the 40s (audiobook). ISBN 978-1-55935-147-8. OCLC 31611854. Tape 1, side B.

- ^ MacKenzie, Bob (1972-10-29). "'40s Sounds Return to Radio" (PDF). Oakland Tribune. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-09. Retrieved 2009-04-03.

- ^ "Perry Como Show-1948-1955". CTVA-Classic TV Archive. Archived from the original on December 24, 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ Smith, Cecil (22 January 1970). "Perry Como's Relaxed As Ever". Toledo Blade. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ a b Sasso, Joey (27 August 1949). "Como Believes in Television". Lewiston Evening Journal. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "Perry Como Will Salute Azalea Fete". Star-News. 24 March 1949. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ Rich, Frank (30 December 2001). "The Lives They Lived-50's-Perry Como B. 1912". New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ^ a b "Chesterfield Supper Club". Internet Archives. 27 November 1949. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ Boyle, Hal (25 January 1955). "Perry Como Turns Down $250,000 A Year To Relax". The Tuscaloosa News. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "The Perry Como Show (video)". Internet Archives. 1952. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ Martinez, James (17 January 1992). "J. Fred missing at Today special". The Robsonian. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ^ O'Brian, Jack (19 September 1955). "'Joe and Mabel' Telecasts Canceled; 'Millie' Continues". Reading Eagle. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- ^ Oviatt, Ray (23 November 1958). "Frank Gallop: The Man Who Goes for 'Breaks'". Toledo Blade. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ Dornbrook, Don (25 January 1959), Perry Como's Announcer Comes Down to Earth, Milwaukee JournalRetrieved 10 June 2010

- ^ Denisova, Maria. Pennsylvania Book-Biographies-Perry Como. Archived from the original on 9 December 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "Regis Philbin recalls Perry Como on TV". Entertainment Weekly. 18 October 1991. Archived from the original on May 25, 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ "We Get Letters". Kokomo. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ "Sing to me, Mr. C." Kokomo. Archived from the original on August 1, 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ "It's impossible! Perry Como actually hated those sweaters". Milwaukee Journal. 24 July 1985.

- ^ "Perry Como TV Lyrics". Archived from the original on 15 August 2004. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ A World of Nice Guys. Time. 15 December 1955. Archived from the original on December 15, 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2010.(subscription required)

- ^ Bell, Joseph N. (9 March 1958). "Perry Como's Formula For Success". The Palm Beach Post. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ Wilson, Earl (13 February 1954). "New York". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Gleason's Ankle, Leg Are Broken". Youngstown Vindicator. 1 February 1954. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Reed, J. D. (28 May 2001). Mister Nice Guy. People. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Torre, Marie (11 March 1959). "Milton Berle Not Moping". Lawrence Journal-World. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ Perry Como Signs $25 million deal. Time. 16 March 1959. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ "Bennett, Brewer, Four Lads Star In Como Summer Show". The Montreal Gazette. 13 June 1959. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "For Perry Como Record TV Contract". Kentucky New Era. 5 March 1959. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ a b Morse, Jim (27 February 1960). "The Most Relaxing Show On Earth-Como And Crosby". The Miami News.

- ^ Lowry, Cynthia (21 February 1963). "Weary Perry Como Sets Limit of 6 Shows Next Year". Schenectady Gazette. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

- ^ Altschuler, Harry (29 May 1965). "What Perry Como Is Doing Now". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ a b Dornbrook, Don (28 April 1960). "TV Trips to London, Paris Provide Refreshing Tonic". Milwaukee Journal.

- ^ Dawson, Greg (17 December 1987). "No Perry Como? Say It Ain't So". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ "Irish Christmas". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ "The Perry Como Show (video)". Internet Archives. 1952. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Perry Como Biography". filmreference.com. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ "Ode To Perry Como". St. Petersburg Times. 26 November 1967. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Time Listings: Feb. 21, 1969. Time. 21 February 1969. Archived from the original on December 14, 2008. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ^ Scott, Vernon (4 February 1970). "Perry Como-Man of Many Moods". The Dispatch. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "Host Perry Como Welcomes Mitzi Gaynor and Art Carney". Rome News-Tribune. 3 December 1971. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "Perry Como back for winter show on Monday night". The Southeast Missourian. 2 December 1972. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ Scheuer, Steven (17 January 1973). "TV Selections for Wednesday". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ "Perry Como Croons In The Yule Sprit". Milwaukee Sentinel. 10 December 1973.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Terrace, Vincent, ed. (1985), Encyclopedia of Television: Series, Pilots and Specials 1974-1984, Baseline Books, pp. 323–324, ISBN 0-918432-61-8, retrieved 2010-04-14

- ^ "'Down Home' Como Style". The Dispatch. 14 February 1975. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ "Christmas With Perry Como". Herald-Journal. 9 December 1978. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Boone, Mike (14 December 1985). "You can always count on Perry Como for a first-class Christmas production". The Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Gardella, Kay (4 December 1986). "Hark! It's 74-year old Perry Como heralding yet another Christmas with a TV special". New York Daily News. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "Ad for Perry Como's Irish Christmas broadcast". Lawrence Journal-World. 5 December 1994. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ "Telethon to seek $250,000 For Rosalia Home Fund". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 23 April 1954. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ "Perry Como Will Visit Pals on Broadway". Miami News. 21 March 1959.

- ^ Oviatt, Ray (14 October 1960). "Hope's Humor Pointless". Toledo Blade. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "Perry Como Appears on Burnett Show". Ludington Daily News. 15 January 1969. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ "Debbie, Perry Join Jones in Tuneful Hour Tonight". The Evening Independent. 6 November 1970. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ^ Drew, Michael H. (14 March 1971). "Doris, Perry, That's Enough". Milwaukee Journal.

- ^ "Perry Como Visits on the Flip Wilson Show". The Sumter Daily Item. 3 October 1970. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "Teenage Girls Choose Como as 'Crooner of Year'". Pittsburgh Press. 19 September 1943. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ a b Thomas, Bob (21 January 1960). "Perry's Doing a Bit Better, These Days". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Winchell, Walter (19 December 1948). "Edgar Bergen Took Out Insurance and Retired". Herald-Journal. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (25 August 1985). "Cool, calm singer Perry Como just missed being a barber". Gainesville Sun. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ LaGumina, Salvatore J.; Cavaioli, Frank J.; Primeggia, Salvatore; Varavalli, Joseph A., eds. (1999), The Italian American Experience: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, pp. 130–133, ISBN 0-8153-0713-6, retrieved 13 April 2010

- ^ Grudens, Richard, ed. (1986), The Italian Crooners Bedside Companion, Celebrity Profiles Publishing, pp. 63–69, ISBN 0-9763877-0-0, retrieved 14 April 2010

- ^ "Swing, Sister, Swing". IMDB. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ "Shorts". Motion Picture Herald. May 9, 1942. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ^ "Garrison, Maxine (30 September 1945). "Canonsburg Barber is Hoofing Now". Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Perry Como and Martha Stewart sing "Hubba, Hubba, Hubba" in this clip from the movie-YouTube

- ^ "Doll Face-Full Movie Download". Internet Archives. 1945. Retrieved 7 June 2010.

External links

- A Perry Como Discography & CD Companion

- The Perry Como Home on the Internet

- Perry Como at IMDb

- Perry Como Collection 1955-1994-University of Colorado at Boulder Archives created by Perry Como, Mickey Glass, and Nick Perito

- Complete List of Perry Como Shows-1948-1955

- Complete List of Perry Como Shows-1955-1959

- Complete List of Perry Como-Kraft Music Hall Shows-1959-1963

Watch

- "Chesterfield Supper Club". Internet Archive. 27 November 1949. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- "Video of "Perry Como Show"". Internet Archive. 16 September 1953.

- "Video of "Perry Como Show"". Internet Archive. 20 January 1954.

- "Video of 1954 "Perry Como Show"". Internet Archive. 1954.

- "1956 episode with commercials removed, runs 52 minutes". Internet Archive. 1956.

- "1959 episode with commercials intact". Internet Archive. 1959.

Listen

- Audio Files-Songs from the Chesterfield Supper Club Radio Show Internet Archive