Pensions in the United Kingdom

Pensions in the United Kingdom, whereby United Kingdom tax payers have some of their wages deducted to save for retirement, can be categorised into three major divisions – state, occupational and personal pensions.

The state pension is based on years worked, with a 35-year work history yielding a pension of £203.85 per week.[1] It is linked to wage and price increases. Most employees and the self-employed are also enrolled in employer-subsidised and tax-efficient occupational and personal pensions which supplement this basic state-provided pension.

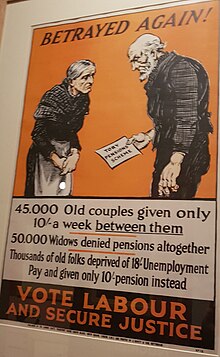

Historically, the "Old Age Pension" was introduced in 1909 in the United Kingdom (which included all of Ireland at that time). Following the passage of the Old Age Pensions Act 1908 a pension of 5/— per week (£0.25, equivalent, using the Consumer Price Index, to £33 in 2023),[2] or 7/6 per week (£0.38, equivalent to £49/week in 2023) for a married couple, was payable to persons with an income below £21 per annum (equivalent to £2800 in 2023); the qualifying age was 70, and the pensions were subject to a means test. The age of eligibility was moved to 65 for men and 60 for women, but, between April 2010 and November 2018, the age for women was raised to match that for men,[3][4] and the retirement age for both men and women is increasing to 68, based on date of birth, and by no later than 2046.[5]

History

Until the 20th century, poverty was seen as a quasi-criminal state,[citation needed] and this was reflected in the Vagabonds and Beggars Act 1494 that imprisoned beggars. In Elizabethan times, English Poor Laws represented a shift whereby the poor were seen merely as morally degenerate,[citation needed] and were expected to perform forced labour in workhouses.

The beginning of the modern state pension was the Old Age Pensions Act 1908, which provided 5 shillings (£0.25) a week for those over age 70 whose annual means did not exceed £31 10s. (£31.50). It coincided with the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress 1905–1909 and was the first step in the Liberal welfare reforms towards the completion of a system of social security, with unemployment and health insurance through the National Insurance Act 1911.

In the early 20th century, occupational (workplace) pension schemes started to become more common, with one driver being the Finance Act 1921 which provided tax-relief on pension scheme contributions.[6]

After the Second World War, the National Insurance Act 1946 completed universal coverage of social security. The National Assistance Act 1948 (11 & 12 Geo. 6. c. 29) formally abolished the poor law, and gave a minimum income to those not paying National Insurance. The Basic State Pension was also introduced in 1948. Occupational pension schemes also flourished after the Second World War, with pensions becoming a key tool to attract and retain staff.[6]

In the second half of the 20th century, there was a succession of legislative changes to protect pension scheme members, prevent abuse of the generous tax-reliefs available and prevent fraudulent activity. Some of these changes were precipitated by Robert Maxwell's plundering of the Mirror Pension Funds.[6] This led to the Goode Report, whose recommendations were implemented by comprehensive statutes in the Pension Schemes Act 1993 and the Pensions Act 1995.

The early 1990s established the existing framework for state pensions in the Social Security Contributions and Benefits Act 1992 and Superannuation and other Funds (Validation) Act 1992.

In 2002 the Pensions Commission was established as a cross-party body to review pensions in the United Kingdom. The first Act to follow was the Pensions Act 2004, which updated regulation by replacing the Occupational Pensions Regulatory Authority (OPRA) with the Pensions Regulator and relaxing the stringency of minimum funding requirements for pensions, while ensuring protection for insolvent businesses. In a major update of the state pension, the Pensions Act 2007 aligned and raised retirement ages. Since then, the Pensions Act 2008 has set up automatic enrolment for occupational pensions, and a public competitor designed to be a low-cost and efficient fund manager, called the National Employment Savings Trust (or "Nest").

Partially as a result of the new regulation, since the turn of the century there has been significant decline in the provision of defined benefit pensions in the private sector,[7] with money purchase arrangements increasingly being used for new benefit accrual.

In November 2023, The Trussell Trust calculated that a single adult in the UK in 2023 needs at least £29,500 a year to have an acceptable standard of living, up from £25,000 in 2022.[8]

On 14 November 2024, Rachel Reeves announced plans to merge pension funds into megafunds to unlock up to £80 billion for investment and boost the UK's economic growth. The reform, set to manage £500 billion by 2030, drew inspiration from similar initiatives in Australia and Canada. While business leaders welcomed the proposal, they expressed concerns about the government's recent budget and its impact on confidence in the UK economy, which has struggled since the 2008 financial crisis.[9]

Pensions Act 2011

The Act amended the timetable for increasing the state pension age to 66. Under the Pensions Act 2007, the increase to 66 was due to take effect between 2024 and 2026. This Act brought forward the increase, so that state pension age for both men and women began rising from 65 in December 2018 and reached 66 in October 2020. As a result of bringing forward the increase to 66, the timetable contained in the Pension Act 1995 for equalising women's and men's state pension ages at 65 by April 2020 was accelerated, so that the women's state pension age reached 65 in November 2018.[10]

The Act introduced amendments to primary legislation to amend the regulatory framework for the duty on employers to automatically enrol eligible workers into a qualifying pension scheme and to contribute to the scheme. These measures implemented recommendations from the Making Automatic Enrolment Work review and revised some of the automatic enrolment provisions in the Pensions Act 2008.

The Act amended existing legislation that provided for revaluation or indexation of occupational pensions and payments by the Pension Protection Fund.

The Act defined "money purchase benefits" for the purpose of pensions law. This was a consequence of the judgment of the Supreme Court in Houldsworth v Bridge Trustees and Secretary of State for Work and Pensions. The Act took powers to make transitional, consequential or supplementary provision as well and to make further amendments to the definition of "money purchase benefits".

The Act introduced provisions into the current judicial pension schemes to allow contributions to be taken towards the cost of providing personal pension benefits to members of those schemes.

The Act also contained a number of measures to correct particular references in the existing body of pensions-related legislation and other small and technical measures to both state and private pension legislation. This included the following measures:

- increased flexibility in the date of consolidation of additional state pension;

- abolition of new awards of Payable Uprated Contracted-out Deduction Increments (PUCODIs);

- Financial Assistance Scheme: amendments to legislation concerning transfer of assets, and amount of payments;

- miscellaneous amendments to Pension Protection Fund legislation;

- amendments to legislation concerning payments of surplus to employers;

- amendments to legislation concerning the requirement for indexation of cash balance benefits; and

- corrective amendments to legislation concerning the calculation of debt owing to a pension scheme.

State pensions

State pension comprises three main elements – the basic pension, additional pensions, and pension guarantee. These are described in the following sections.

Basic State Pension (BSP) or State Retirement Pension

Additional Pension

Three different state schemes have existed to provide extra pension provision above the Basic State Pension (BSP). These are collectively known as Additional Pension. They have been available only to employees paying National Insurance contributions and to certain exempted groups (not including the self-employed). The three schemes are/were:

- Graduated Pension or Graduated Retirement Benefit: This was earned between 6 April 1961 and 5 April 1975. Qualification was based on the amount of contributions paid, which are used to buy ‘units’. The value of a unit is £7.50 for men and women.[11] Graduated pension typically pays a small amount (£1 or so per week) to those entitled to it.

- State Earnings-Related Pension Scheme (SERPS): SERPS ran from 6 April 1978 to 5 April 2002. As the name implies, the level of pension payable was related to earnings via the amount of National Insurance contributions. Qualification was based on band earnings above a Lower Earnings Limit (LEL) in each year. The LEL (£84 per week /£4368 pa in 2006/07) was usually set at the same level as the BSP (£84.25) and increased when BSP did. Band earnings were those between the LEL and an Upper Earnings Limit (UEL) at which National Insurance contributions ceased to be payable by the employee (this was £645 per week/£2,795 per month in 2006/07, although the UEL now refers to a threshold where reduced NI payments are made, as opposed to payment ceasing). The UEL is also adjusted annually.

- State Second Pension (S2P): S2P was introduced on 6 April 2002. As with SERPS, the level of pension payable is related to the recipient's earnings via their National Insurance contributions. Qualification is based on earnings at, or above, the LEL, but no band earning calculation is made until earnings reach a higher base (£12,500 pa in 2006/07) called the Lower Earnings Threshold (LET). Earnings below the LET (but above the LEL) are credited up to the LET.

Unlike the Basic State Pension, participation in the Additional Pension schemes is voluntary. Those who do not wish to participate can contract out. This option was introduced with SERPS in 1978 and is only available to those who have made alternative pension arrangements through Personal or Occupational schemes. Further changes to be introduced in 2012 will see S2P change from an "earnings related" to a "flat rate" pension, and individuals will lose the right to contract out.

Pension Credit

Occupational pensions

Occupational pension schemes are arrangements established by employers to provide pension and related benefits for their employees. These are created under the Pension Schemes Act 1993, the Pensions Act 1995 and the Pensions Act 2008.

Automatic enrolment

The Pensions Act 2008 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The principal change brought about by the Act is that all workers will have to opt out of an occupational pension plan of their employer, rather than opt in. This is referred to as automatic enrolment, and moves a significant amount of responsibility onto the employer to ensure that their employees are enrolled in a workplace pension scheme.[12] Research based on ONS labour market data has found that partly due to the equalisation of the state pension age, women are driving employment growth in the UK and that the number of females over 65 working doubled in the 10 years between 2009 and 2019.[13]

Employers were required to initiate automatic enrolment into their workplace according to set staging dates based on the number of employees in the company. These dates varied from 1 January 2012 to 1 January 2017, with larger firms required to meet compliance guidelines first, and smaller firms later.[14] There were penalties for companies who are not compliant by their staging date.[15] There are a number of solutions available to help companies meet government compliance by their staging date, an example of this would be NEST which was set up by the government.[16]

Between the introduction of auto enrolment and April 2016, "the overall proportion of eligible employees saving into a workplace pension increased from 55% to 78%" with the largest increases found in the private sector.[17]

In July 2023, the Department for Work and Pensions announced that small pots worth less than £1000 would be consolidated into larger schemes in order to tackle an issue that had been exacerbated unintentionally by auto-enrolment, the problem of lost pension pots. Every time a worker switched jobs they would open a new scheme, meaning many workers had lots of pots and had difficulty keeping track of them. By consolidating the pots would be easier to keep track of, potentially generate higher growth, and not suffer from higher fees. [18]

Defined benefit/final salary schemes

Defined benefit schemes are pension schemes which provide a defined (i.e. guaranteed) level of benefit, such as "1/60 of your salary at retirement for each year of service". In such an arrangement, the employee was typically promised a pension of a fixed proportion of their salary in the period leading up to retirement or as an average of earnings over their career. The proportion would depend on the number of years of service with the employer. Post retirement increases are typically partly discretionary, however, must comply with statutory minimums.[19]

These schemes were common place in the second half of the 20th century (and are still used in the public sector), but declined significantly at the start of the 21st century in the private sector as the costs associated with these schemes increased substantially. These cost increases were driven by various factors, including an increase in life expectancy, the dot-com bubble bursting, a reduction in bond yields and increasing regulation.[6]

Defined contribution/money purchase schemes

Over recent years, many employers have closed their defined benefit schemes to new members, and established defined contribution or money purchase arrangements instead. In this arrangement, the employer (and sometimes also the employee) makes regular payments (typically a percentage of salary) into a pension fund, and the fund is used to buy a pension when the employee retires. So the amount of pension depends on a number of factors including the accumulated amount of the fund, interest rates and projected mortality rates at the time the individual retires.

Funding

UK occupational pension schemes are typically jointly funded by the employer and the employees. These are called "contributory pension schemes" since the employee contributes. "Non contributory pension schemes" are where the employer funds the scheme with no contribution from the individual. Contributions are put into a separate trust, whose assets will be used to provide benefits in due course.

Underfunding

Defined benefit pension schemes may be affected to swings in the financial markets. The Pension Protection Fund was set up to act as a safety net in case a scheme was unable to pay the defined benefits it was committed to. According to the PPF, pension funds in the UK are estimated to have been £367.5 billion in deficit at the end of January 2015. The report[20] puts the deficit at 40%. The PPF figures show that the funds fell into overall deficit at the end of 2011. The situation of the schemes is driven largely by quantitative easing.[21][22] By December 2019 the PPF estimated the total deficit of all pension funds in the U.K. to be £35.4 billion.[23]

Tax registration

Most schemes are also registered for tax purposes, which gives the scheme various tax advantages—assets grow free from income tax, capital gains tax and corporation tax, employees can normally make contributions out of their gross (untaxed) income, and employer contributions are generally tax deductible. Only funded schemes can be registered.

Prior to April 2006 schemes were 'approved' by HMRC rather than registered. Approval placed certain limits on the benefits which could be provided, which led to a growth of 'unapproved' (i.e. without the generous tax treatment) retirement arrangements—these unapproved schemes were commonly distinguished by reference to their funding status (funded unapproved retirement benefit schemes FURBS and unfunded unapproved retirement benefit schemes UURBS).

Individual or personal pensions

It is also possible for an individual to make contributions under an arrangement they themselves make with a provider (such as an insurance company). Similar tax advantages will usually be available as for occupational schemes. Contributions are typically invested during an individual's working life, and then used to purchase a pension at or following retirement. Various names are given to different types of individual arrangement, but they are not fundamentally different in nature. The generic term personal pension is used to refer to arrangements established since the rules were liberalised in the 1980s (earlier arrangements are usually called retirement annuity contracts), but can be subdivided into other types (such as the self-invested personal pension, where the member is allowed to direct what their contributions should be invested in).

Stakeholder pensions

Stakeholder pensions (insured personal pensions, with charges capped at a low level) are a form of pension arrangement designed to be easily understandable and available. Stakeholder pensions are in effect personal pension schemes set up on terms which meet standards set by the government (for example there are restrictions on the charges the provider may make). Although a stakeholder pension is a personal pension, they can (and in some circumstances must) be offered by an employer as a cost-effective way of providing pension cover for their workforce.

Group personal pensions

Group personal pensions are another pension arrangement that are personal pensions, but are linked to an employer.[citation needed] A group personal pension plan (GPPP) can be established by an employer as a way of providing all of its employees with access to a pension plan run by a single provider. By grouping all the employees together in this way, it is normally possible for the employer to negotiate favourable terms with the provider, thus reducing the cost of pension provision to the employees. The employer will also normally contribute to the GPPP.

SIPPs

Special categories of pension

Perpetual or hereditary pensions

Perpetual pensions were freely granted either to favourites or as a reward for political services from the time of Charles II onwards. Such pensions were very frequently attached as salaries to places which were sinecures, or, just as often, resulted in grossly overpaid posts which were really unnecessary, while the duties were discharged by a deputy at a small salary.

Prior to the reign of Queen Anne, such pensions and annuities were charged on the hereditary revenues of the sovereign and were held to be binding on the sovereign's successors.[24] By the Taxation, etc. Act 1702 (1 Ann. c. 7) it was provided that no portion of the hereditary revenues could be charged with pensions beyond the life of the reigning sovereign. This act did not affect the hereditary revenues of Ireland and Scotland, and many persons were quartered, as they had been before the act, on the Irish and Scottish revenues who could not be provided for in England for example, the Duke of St Albans, illegitimate son of Charles II, had an Irish pension of £800 a year (equivalent to £160,347 in 2023); Catherine Sedley, mistress of James II, had an Irish pension of £5,000 a year; the Duchess of Kendal and the Countess of Darlington, respectively mistress and half-sister of George I, had pensions of the united annual value of £5,000 (equivalent to £596,135 in 2023), while Madame de Wallmoden, a mistress of George II, had a pension of £3,000 (equivalent to £548,983 in 2023).[25]

These pensions had been granted in every conceivable form during the pleasure of the Crown, for the life of the sovereign, for terms of years, for the life of the grantee, and for several lives in being or in reversion.[26] On the accession of George III and his surrender of the hereditary revenues in return for a fixed civil list, this civil list became the source from which the pensions were paid. The three pension lists of England, Scotland and Ireland were consolidated in 1830, and the civil pension list reduced to finance the remainder of the pensions being charged on the Consolidated Fund.

In 1887 Charles Bradlaugh MP protested strongly against the payment of perpetual pensions, and as a result a committee of the House of Commons inquired into the subject.[27] An appendix to the report contains a detailed list of all hereditary pensions, payments and allowances in existence in 1881, with an explanation of the origin in each case and the ground of the original grant; there are also shown the pensions, etc., redeemed from time to time, and the terms upon which the redemption took place. The nature of some of these pensions may be gathered from the following examples:

- To the Duke of Marlborough and his heirs in perpetuity, £4,000 per annum; this annuity was redeemed in August 1884 for a sum of £107,780, by the creation of a ten years annuity of £12,796/17/-. per annum.

- By the Lord Nelson (Annuity) Act 1806 (46 Geo. 3. c. 146) an annuity of £5,000 per annum was conferred on Earl Nelson and his heirs in perpetuity.

- In 1793 an annuity of £2,000 was conferred on Lord Rodney and his heirs.

All these pensions were for services rendered, and although justifiable from that point of view, a preferable policy is pursued in the 20th century, by Parliament voting a lump sum, as in the cases of Lord Kitchener in 1902 (£50,000) and Lord Cromer in 1907 (£50,000).

Charles II granted the office of Receiver-General and Controller of the Seals of the Court of Kings Bench and Common Pleas to the Duke of Grafton. This was purchased in 1825 from the duke for an annuity of £843, which in turn was commuted in 1883 for a sum of £22,714/12/8. To the same duke was given the Office of the Pipe or Remembrancer of First-Fruits and Tenths of the Clergy. This office was sold by the duke in 1765 and, after passing through various hands, was purchased by one R. Harrisor in 1798. In 1835 on the loss of certain fees the holder was compensated by a perpetual pension of £62/9/8. The Duke of Grafton also possessed an annuity of £6,870 in respect of the commutator of the dues of butlerage and prisage.

To the Duke of St Albans was granted in 1684 the office of Master of the Hawks. The sum granted by the original patent were: Master of Hawks, salary £391/1/5.; four falconers at £50 per annum each, £200; provision of hawks, £600; provision of pigeons, hens and other meats £182/10/-.; total, £1373/11/5. This amount was reduced by office fees and other deductions to £965, at which amount it stood until commuted in 1891 for £18,335.

To the Duke of Richmond and his heirs was granted in 1676 a duty of one shilling per ton of all coals exported from the Tyne for consumption in England. This was redeemed in 1799 for an annuity of £19,000 (chargeable on the Consolidated Fund), which was afterwards redeemed for £633,333.

The Duke of Hamilton, as hereditary keeper of the palace of Holyrood House, received a perpetual pension of £45,105 and the descendants of the heritable usher of Scotland drew a salary of £242/10/-.

The conclusions of the committee were that pensions allowances and payments should not in future be granted in perpetuity, on the ground that such grants should be limited to the persons actually rendering the service, and that such reward should be defrayed by the generation benefited; that offices with salaries and without duties, or with merely nominal duties, ought to be abolished; that all existing perpetual pensions and payments and all hereditary offices should be abolished: that where no service or merely nominal service is rendered by the holder of an hereditary office or the original grantee of a pension, the pension or payment should in no case continue beyond the life of the present holder and that in all cases the method of commutation ought to ensure a real and substantial saving to the nation (the existing rate, about 27 years purchase, being considered by the committee to be too high). These recommendations of the committee were adopted by the government and outstanding hereditary pensions were gradually commuted, the only ones left outstanding being those to Lord Rodney (£2,000) and to Lord Nelson (£5,000), both chargeable on the Consolidated Fund. Neither of these pensions is currently active, the Rodney Pension was commuted in 1924 for a sum of £42,000,[28] and the Nelson Pension was ended as a result of the Trafalgar Estate Act 1947. This Act allowed for the pension to continue to be paid to the then-current recipient and his heir, and provided for payments to cease on the death of the heir.[29]

Political pensions

These are type sui generis as they either reward a career in domestic politics or are awarded in the colonial context not on grounds of justice, contract or socio-economic merits, but as a political decision, in order to take a politically significant person (often deemed a potential political danger) out of the picture by paying him or her off, regardless of seniority.[citation needed]

Civil List pensions

These are pensions granted by the sovereign from the Civil List upon the recommendation of the First Lord of the Treasury. They were to be "granted to such persons only as have just claims on the royal beneficence or who by their personal services to the Crown, or by the performance of duties to the public, or by their useful discoveries in science and attainments in literature and the arts, have merited the gracious consideration of their sovereign and the gratitude of their country."[30] As of 1911, a sum of £1,200 was allotted each year from the Civil List, in addition to the pensions already in force. In 1908, the total of civil list pensions payable in that year amounted to £24,665. For 2012–13 the total annual cost of civil list pensions paid to 53 people was £126,293. The average pension was £2,383.[31]

Judicial, municipal, etc. pensions

There are certain offices of the executive whose pensions are regulated by particular acts of Parliament. Judges of the High Court, on completing fifteen years' services or becoming permanently incapacitated for duty, whatever their length of service, may be granted a pension equal to two-thirds of their salary (Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1873). Historically the Lord Chancellor of Great Britain, however short a time he may have held office, received a pension of half his salary. The Public Service Pensions Act 2013 (c. 25) abolished this arrangement, and subsequent Lord Chancellors have participated in the Ministerial Pension Scheme.[32]

Local authorities contribute to pensions in the Local Government Pension Scheme using powers in the Superannuation Act 1972.

Ecclesiastical pensions

Bishops, deans, canons or incumbent who are incapacitated by age or infirmity from the discharge of their ecclesiastical duties may receive pensions which are a charged upon the revenues of the see or cure vacated.

Royal Navy – historical

Navy pensions were first instituted by William III of England in 1693 and regularly established by an order in council of Queen Anne in 1700. Since then the rate of pensions has undergone various modification and alterations; the full regulations concerning pensions to all ranks will be found in the quarterly Navy List, published by authority of the Admiralty. In addition to the ordinary pension there are also good-service pensions, Greenwich Hospital pension and pensions for wounds.

An officer was entitled to a pension when he retired at the age of 45, or if he retired between the ages c 40 and 45 at his own request, otherwise he received only half pay. The amount of his pension depended upon his rank, length of service and age. As an example, in past, the maximum retired pay of an admiral was £850 per annum, for which 30 years' service or its equivalent in half-pay time was necessary; he may, in addition, have held a good service pension of £300 per annum. The maximum retired pay of a vice-admiral with 29 years' service was £725; of rear-admirals with 27 years' service, £600 per annum. Pensions of captains who retire at the age of 55, commanders, who retire at 50, and lieutenants who retire at 45, ranged from £200 per annum for 17 years' service to £525 for 24 years' service. The pensions of other officers were calculated in the same way, according to age and length of service.

The good-service pensions consisted of ten pensions of £300 per annum for flag-officers, two of which may be held by vice-admirals and two by rear-admirals; twelve of £150 for captains; two of £200 a year and two of £150 a year for engineer officers; three of £100 a year for medical officers of the navy; six of £200 a year for general officers of the Royal Marines and two of £150 a year for colonels and lieutenant-colonels of the same. Greenwich Hospital pensions range from £150 a year for flag officers to £25 a year for warrant officers. All seamen and marines who have completed twenty-two years' service were entitled to pensions ranging from 1d a day to a maximum of 1/2 a day, according to the number of good-conduct badges, together with the good-conduct medal, possessed. Petty officers, in addition to the rates of pension allowed them as seamen, were allowed for each year's service in the capacity of superior petty officer, 15/2 a year, and in the capacity of inferior petty officer 7/7 a year.

Men who were discharged from the service on account of injuries and wounds or disability attributable to the service were pensioned with sums varying from 6d a day to 2/- a day. Pensions were also given to the widows of officers in certain circumstances and compassionate allowances made to the children of officers. In the Navy estimates for 1908–1909 the amount required for halfpay and retired-pay was £868,800, and for pensions, gratuities and compassionate allowances £1,334,600, a total of £2,203,400.

Navy pensions were updated in 1975 with the Armed Forces Pension Scheme 1975 Regulations.[33]

Modern armed forces

Members of all three modern armed forces are members of the Armed Forces Pensions Scheme, which is a career average defined benefit pension scheme, and is described by the government as one of the most generous pensions available in the UK today.[34] One key feature of the current scheme (dating from 2015) is that members pay no employee contribution, with the pension being entirely funded from the public purse. Each year a scheme member accumulates 1/47th of their salary, with a retirement age of 60. The annual pension payment increases each year in line with the Consumer Price Index.[35]

Pension provision by age group

The family resources survey[36] from the UK Department for Work and Pensions, details levels of income, saving and pension provision for a representative selection of UK households and is the source for the table below for UK employees (Table 7.12):

| Pension provision level | 16–24 age group | 25–34 age group | 35–44 age group | 45–54 age group | 55–59 age group | 60–64 age group | 65+ age group | Working-age male | Working-age female | All adult employees | All self-employed adults |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupational pension | 15% | 41% | 51% | 52% | 49% | 33% | 2% | 44% | 46% | 42% | 1% |

| Personal or stakeholder pension | 1% | 8% | 11% | 11% | 11% | 8% | 3% | 12% | 7% | 9% | 30% |

| Both occupational and personal pension | 0 | 1% | 2% | 3% | 3% | 2% | 0 | 2% | 2% | 2% | 0 |

| Not in any pension scheme | 83% | 49% | 36% | 34% | 37% | 56% | 95% | 42% | 46% | 47% | 68% |

Most employees over the state pension age of 65 would not have pension provision as part of their salary and benefits—they may well, however, be receiving income from a pension from previous employment.

See also

- History of the welfare state in the United Kingdom

- Association of Pension Lawyers

- Gender pension gap

- Pensions in Germany

- Pensions in the United States

- Ageing of Europe

- Pension tax simplification

- Minimum funding requirement

- Frozen pension

- Superannuation in Australia

- Pensions in Canada

- Personal pension scheme

State pensions acts

- Widows', Orphans' and Old Age Contributory Pensions Act 1925 (15 & 16 Geo. 5. c. 70)

- National Insurance Act 1946

- National Insurance Act 1965

- Social Security Contributions and Benefits Act 1992

Private pensions acts

- Superannuation and other Funds (Validation) Act 1992

- Pension Schemes Act 1993

- Pensions Act 1995

- Pensions Act 2004

- Pensions Act 2007

- Pensions Act 2008

Auto-enrolment solutions

Notes

- ^ "The new State Pension". GOV.UK. 1 August 2023. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "The new State Pension". GOV.UK.

- ^ "Background relating to changes in State Pension age for women".

- ^ "[ARCHIVED CONTENT] Changes to the planned increase in State Pension age : Directgov – Newsroom". nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d Rhodes, Matthew (2021). The Story of UK Pensions. Matthew Rhodes. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-8384320-0-3.

- ^ John Kay; Mervyn King (2020). Radical Uncertainty. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 312–313. ISBN 9781324004776.

- ^ Este, Jonathan (10 November 2023). "How much income is needed to live well in the UK in 2023? At least £29,500 – much more than many households bring in". The Conversation. Retrieved 12 November 2023.

- ^ PYLAS, PAN (14 November 2024). "UK set to create new pension megafunds with aim of unlocking $100 billion for investment". AP News. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

- ^ Pensions Act 2011

- ^ Prior to 6 April 2010, a woman’s unit was worth £9. Graduated Retirement Benefit (GRB) explained, SunLife

- ^ "Workplace Pensions – Automatic Enrolment – The Pensions Regulator". thepensionsregulator.gov.uk.

- ^ "Women Over the Age of 50 Have Driven 42% of UK Employment Growth in the Last 10 Years". Rest Less. 19 March 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ "New timetable clarifies automatic enrolment starting dates". gov.uk.

- ^ "What Happens If I Don't Comply?". The Pensions Regulator.

- ^ "About Nest".

- ^ "Automatic enrolment: Commentary and analysis: April 2016 – March 2017" (PDF). The Pensions Regulator. July 2017.

- ^ Ruth Emery (11 July 2023). "Small pension pots to be consolidated, says DWP". moneyweekuk. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Pension basics | Help with pension basics | MoneyHelper".

- ^ "Welcome to the PPF" (PDF).

- ^ "Pension deficits at record high as contributions threaten to choke business". The Telegraph. 10 February 2015.

- ^ "European companies dig deeper to fill pension holes". Financial Times. 8 February 2015.

- ^ "August 2021 update of Pension Protection Fund".

- ^ The Bankers Case, 1691; State Trials, xiv. 3–43

- ^ Lecky, William Edward Hartpole (1892). A History of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century.

- ^ Erskine May, Thomas (1862). The Constitutional History of England since the Accession of George III, 1760–1860.

- ^ Report of Select Committee on Perpetual Pensions, 248, 1887

- ^ "Willing to Commute Lord Rodney's Pension; Descendant of British Naval Hero Offers Quittance to Government for 42,000". New York Times. 11 March 1924. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ "Hansard 24 April 1947 - Trafalgar Estates Bill".

- ^ Civil List Act 1837 (c.2)

- ^ "Written Answers to Questions". House of Commons Hansard. 17 June 2013. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Commons Library (13 January 2022). "Pensions of ministers and senior office holders". Parliament.uk.

- ^ "Armed Forces Pension Scheme 1975 Regulations". gov.uk. 20 May 2019.

- ^ "Armed forces pensions". gov.uk.

- ^ "Armed Forces Pension Scheme 2015" (PDF). gov.uk.

- ^ Family Resources Survey 2005–06 Archived 11 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine

References

- Books

- Matthew Rhodes, 'The Story of UK Pensions' (2021), ISBN 9781838432003

- L Hannah, Inventing Retirement (1986) HD7165 H24

- Articles

- T Schuller and J Hyman, 'Pensions: The Voluntary Growth of Participation' (1983) 14(1) Industrial Relations Journal 70

- Reports

- White Paper, Occupation Pension Schemes: The Role of Members in the Running of Schemes (1976) Cmnd 6514

- Wilson Report (June 1980) Cmnd 7937

- R Goode, Pension Law Reform (1993) Cm 2342

External links

- Pension Wise – A free and impartial government service about your defined contribution pension options.

- Association of Member-Directed Pension Schemes (AMPS) – The principal body for discussing changes involved in the area of pension planning.

- Pensions and retirement planning (Directgov)

- "Pensions Bill 2007 – Impact Assessment" (PDF). Department for Work and Pensions. 5 September 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2009.

- Money Alive

- Chartercross Capital Management – Simple Impartial Advice.