Palace Museum

故宫博物院 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Front view of the Museum[note 1] | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Established | 10 October 1925 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | 4 Jingshan Front St, Dongcheng, Beijing | ||||||||||

| Coordinates | 39°55′01″N 116°23′27″E / 39.91694°N 116.39083°E | ||||||||||

| Type | |||||||||||

| Collection size | 1,860,000 | ||||||||||

| Visitors | 17 million (2018)[1] | ||||||||||

| Director | Wang Xudong | ||||||||||

| Public transit access | 1 at Tian'anmendong 2 8 at Qianmen | ||||||||||

| Website |

| ||||||||||

| Built | 1406–1420 | ||||||||||

| Architect | Kuai Xiang | ||||||||||

| Architectural style(s) | Chinese architecture | ||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 故宫博物院 | ||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Former-Palace Museum | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

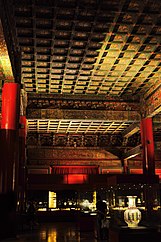

The Palace Museum (Chinese: 故宫博物院; pinyin: Gùgōng Bówùyùan), also known as the Beijing Palace Museum,[2][3][4] is a large national museum complex housed in the Forbidden City at the core of Beijing, China. With 720,000 square metres (180 acres), the museum inherited the imperial royal palaces from the Ming and Qing dynasties of China and opened to the public in 1925 after the last Emperor of China was evicted.

Constructed from 1406 to 1420, the museum consists of 980 buildings.[5] It is home to over 1.8 million pieces of art, mostly from the imperial collection of the Ming and Qing dynasties. The 20th century saw its expansion through new acquisitions, transfers from other museums, and new archaeological discoveries.

According to the Beijing Evening Post, the museum has seen more than 17 million visitors in 2018, making it the world's most visited museum. It has an average of 15 million visitors annually since 2012.[6][7] Due to this increased pressure, the management has set a daily limit for visitors of 80,000 since 2015 to protect the structure and the experience.[8]

History

Palace

The Palace Museum is housed in the Forbidden City, the Chinese imperial palace from the Ming dynasty to the end of the Qing dynasty. It is located in the middle of Beijing, China. For almost five centuries, it served as the home of the emperor and his household, and the ceremonial and political centre of Chinese government.

Built from 1406 to 1420, the complex consists of 980 surviving buildings with 8,707 bays of rooms[9] and covers 720,000 square metres (7,800,000 sq ft). The palace complex exemplifies traditional Chinese palatial architecture,[10] and has influenced cultural and architectural developments in East Asia and elsewhere. The Forbidden City was declared a World Heritage Site in 1987,[10] and is listed by UNESCO as the largest collection of preserved ancient wooden structures in the world.

Museum

In 1912, Puyi, the last emperor of China, abdicated. Under an agreement with the new Republic of China government, Puyi remained in the Inner Court, while the Outer Court was given over to public use,[11] where a small museum was set up to display artifacts housed in the Outer Court. In 1924, Puyi was evicted from the Inner Court after a coup.[12] The Palace Museum was then established in the Forbidden City on Double Ten Day (October 10), 1925.[13]

The collections of the Palace Museum are based on the Qing imperial collection. According to the results of a 1925 audit, some 1.17 million pieces of art were stored in the Forbidden City.[14] In addition, the imperial libraries housed countless rare books and historical documents, including government documents of the Ming and Qing dynasties.[15]

From 1933, the threat of Japanese invasion forced the evacuation of the most important parts of the museum's collection.[16] After the end of World War II, this collection was returned to Nanjing.[17] However, with the Chinese Communist Party's victory imminent in the Chinese Civil War, the Nationalist government under Chiang Kai-shek ordered the evacuation of the pick of this collection to Taiwan. Of the 13,491 boxes of evacuated artifacts, 2,972 boxes are now housed in the National Palace Museum in Taipei. This relatively small but high-quality collection today forms the core of that museum.[18] More than 8,000 boxes were returned to Beijing, but 2,221 boxes remain today in storage under the charge of the Nanjing Museum.[18]

Under the government of the People's Republic of China, the museum conducted a new audit as well as a thorough search of the Forbidden City, uncovering a number of important items. In addition, the government moved items from other museums around the country to replenish the Palace Museum's collection. It also purchased and received donations from the public.[19]

Collections

Today, there are over a million rare and valuable works of art in the permanent collection of the Palace Museum,[20] including paintings, ceramics, seals, steles, sculptures, inscribed wares, bronze wares, enamel objects, etc. The collections of the Palace Museum are based on the Qing imperial collection. According to the results of a 1925 audit, some 1.17 million pieces of art were stored in the Forbidden City.[14] From 1933, the threat of Japanese invasion forced the evacuation of the most important parts of the museum's collection. After the end of World War II, this collection was returned to Nanjing. However, with the Chinese Communist Party's victory imminent in the Chinese Civil War, the Nationalist government decided to ship the pick of this collection to Taiwan. Of the 13,491 boxes of evacuated artifacts, 2,972 boxes are now housed in the National Palace Museum in Taipei. More than 8,000 boxes were returned to Beijing, but 2,221 boxes remain today in storage under the charge of the Nanjing Museum.[18] According to an inventory of the museum's collection conducted between 2004 and 2010, the Palace Museum holds a total of 1,807,558 artifacts and includes 1,684,490 items designated as nationally protected "valuable cultural relics."[21] At the end of 2016, the Palace Museum held a press conference, announcing that 55,132 previously unlisted items had been discovered in an inventory check carried out from 2014 to 2016. The total number of items in the Palace Museum collection is presently at 1,862,690 objects.[22]

Ceramics

The Palace Museum holds 340,000 pieces of ceramics and porcelain. As well as other pieces, these include imperial collections from the Tang and Song dynasties, as well as pieces commissioned by the palace, and, sometimes, by the emperor personally. This collection is notable because it derives from the imperial collection, and thus represents the best of porcelain production in China; other large collections are in the National Palace Museum in Taipei and the Nanjing Museum.

The ceramic collection of the Palace Museum represents a comprehensive record of Chinese ceramic production over the past 8,000 years, as well as one of the largest such collections in the world.[19]

Painting

The Palace Museum holds close to 50,000 paintings. Of these, more than 400 date from before the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). This is the largest such collection in China and includes some of the rarest and most valuable paintings in Chinese history.[23]

The collection is based on the palace collection of the Ming and Qing dynasties. The personal interest of emperors such as Qianlong meant that one of the most important collections of paintings in Chinese history was held at the palace. However, a significant portion of this collection was lost. After his abdication, Puyi transferred paintings out of the palace, and many of these were subsequently lost or destroyed. In 1948, some of the best parts of the collection were moved to Taiwan. The collection has since been gradually replenished, through donations, purchases, and transfers from other museums.

Jade

Jade has a unique place in Chinese culture.[24] The museum's collection, mostly derived from the imperial collection, includes some 30,000 pieces. The pre-Yuan dynasty part of the collection includes several pieces famed throughout history, as well as artifacts from more recent archaeological discoveries. The earliest pieces date from the Neolithic period. Ming dynasty and Qing dynasty pieces, on the other hand, include both items for palace use, as well as tribute items from around the empire and beyond.[25]

Sculpture

Bronzeware

Bronze holds an important place in Chinese culture, and was always an important part of state ceremony. The Palace Museum's bronze collection dates from the early Shang dynasty. Of the almost 10,000 pieces held, about 1600 are inscribed items from the pre-Qin period (to 221 BC). A significant part of the collection is ceremonial bronzeware from the imperial court, including complete sets of musical instruments used by the imperial orchestras.[26]

Timepiece

The Palace Museum has one of the largest collections of mechanical timepieces of the 18th and 19th centuries in the world, with more than 1,000 pieces. The collection contains both Chinese- and foreign-made pieces. Chinese pieces came from the palace's own workshops, Guangzhou (Canton) and Suzhou (Suchow). Foreign pieces came from countries including Britain, France, Switzerland, the United States and Japan. Of these, the largest portion come from Britain.[27]

Notable pieces in the collection include a clock with an attached automaton which is able to write, with a miniature writing brush on inserted paper, an auspicious couplet in perfect Chinese calligraphy.[28]

Palace artifact

In addition to works of art, a large proportion of the museum's collection consists of the artifacts of the imperial court. This includes items used by the imperial family and the palace in daily life, as well as various ceremonial and bureaucratic items important to government administration. This comprehensive collection preserves the daily life and ceremonial protocols of the imperial era.[29]

Exhibitions

The permanent exhibitions of the museum can be divided into two types, one is the as-was exhibition (Chinese: 原状陈列), one is the themed exhibitions (Chinese: 专馆). The as-was exhibitions present the rooms in similar manners as the imperial time. There are eleven dedicated themed exhibitions halls:

- Digital

- Painting & Calligraphy

- Ceramic

- Treasury

- Timepiece

- Sculpture

- Architecture

- Bronzeware

- Xiqu

- Arsenal

- Furniture

Academics

The Palace Museum operates several academic organizations. The major two are the Palace Academy and the Palace Research Institute. It also hosts the Forbidden City Society, the Society of the Qing Palatial History, and the National Laboratory of Ancient Ceramics for Research and Preservation.[30]

Research

The Palace Research Institute is headed by Zheng Xinmiao. It is the publisher of the Palace Museum Journal (故宫博物院院刊), Journal of Gugong Studies (故宫学刊). It has numerous research labs.

Conservation

The Hospital for Conservation is the conservation branch of the museum responsible for the maintenance and conservation of the artifacts. It has several laboratories and studios responsible for the research and restoration of artifacts of different types. The laboratories are:

- Basic Analysis Lab

- Organic Conservation Lab

- Biology Lab

- Environmental Monitoring & Control Lab

- Inorganic Conservation Lab

- Historical Architecture Conservation Lab

- Sample Preparation Lab

- Computed Tomography Lab

- Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Lab

The studios are:

- Conservation Studio for Ceramics : Enamel Conservation, Ceramics Conservation, Stone Conservation

- Packaging Studio for Packaging : Package Design and Making

- Restoration Studio for Inlay Work : Restoration of Inlay Works.

- Restoration Studio for Lacquer: Lacquer Restoration

- Restoration Studio for Woodware : Furniture Restoration, Wooden Sculpture Restoration,

- Conservation Studio for Textile : Textile Conservation

- Restoration and Replication Studio for Bronzeware : Bronzeware Conservation

- Studio for the Mounting of Calligraphy and Painting

- Replication Studio for of Calligraphy and Painting

- Restoration Studio for Timepiece: Timepiece Restoration

- Studio for Digital Replication

- Studio for Diverse Arts: Thangka Restoration, Mural Restoration, Oil Painting Restoration

Administration

The curator of the museum is Wang Xudong, formerly director of Dunhuang Research Academy.[31]

His predecessor Shan Jixiang is well reputed for his many reforms of the institution.[32]

Satellite and sister museums

- Kulangsu Gallery of Foreign Artifacts from the Palace Museum Collection in Kulangsu, Xiamen.

- Northern Branch of the Palace Museum in Xibeiwang, Haidian, Beijing, under construction since December 2022.[33]

- Hong Kong Palace Museum in Hong Kong, opened in July 2022.

- National Palace Museum, in Taipei, Taiwan, shares the same root but split after Chinese Civil War

Performance

- Live Performance concert venue

The Forbidden City has also served as a performance venue. However, its use for this purpose is strictly limited, due to the heavy impact of equipment and performance on the ancient structures. Almost all performances said to be "in the Forbidden City" are held outside the palace walls.

- In 1997, Greek-born composer and keyboardist Yanni performed a live concert in front of the Forbidden City the first modern Western artist to perform at the historic Chinese site. The concert was recorded and later released as part of the Tribute album.[34]

- Giacomo Puccini's opera, Turandot, the story of a Chinese princess, was performed at the Imperial Shrine just outside the Forbidden City for the first time in 1998.[35]

- In 2001, the Three Tenors, Plácido Domingo and José Carreras and Luciano Pavarotti, sang in front of Forbidden City main gate as one of their performances.

- In 2004, the French musician Jean Michel Jarre performed a live concert in front of the Forbidden City, accompanied by 260 musicians, as part of the "Year of France in China" festivities.[36]

Notes

- ^ The main gate, the Gate of Divine Might, is now exit only.

References

- ^ Du, Juan (December 17, 2018). "Palace Museum sees record number of visitors". China Daily. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ "China's Forbidden City admits plans for 'rich club'". BBC News. 2011-05-17. Retrieved 2024-11-10.

- ^ Gilani, Fazal (2022-02-24). "Digitalizing Gandhara Art, Exhibition at the Palace Museum in Beijing in 2022". Gwadar Pro. Retrieved 2024-11-10 – via China Economic Net.

- ^ "Bringing the Palace Museum's treasures to life". Hong Kong Baptist University. 28 Jul 2022. Retrieved 2024-11-10.

- ^ 故宫到底有多少间房 [How many rooms in the Forbidden City]. Singtao Net (in Simplified Chinese). 27 September 2006. Archived from the original on 18 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ "Visitors to Beijing Palace Museum Topped 16 Million in 2016, An Average of 40,000 Every Day". thebeijinger.com. 3 January 2017.

- ^ Bi (毕), Nan (楠). "Beijing's Forbidden City ranks most visited museum in the world – Chinadaily.com.cn". hinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- ^ "Forbidden City becomes world's most visited museum". gbtimes.com. Archived from the original on 2019-06-04. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- ^ "故宫到底有多少间房 (How many rooms in the Forbidden City)" (in Chinese). Singtao Net. 2006-09-27. Archived from the original on 2007-07-18. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ a b "UNESCO World Heritage List: Imperial Palaces of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Beijing and Shenyang". UNESCO. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ p 137, Yang (2003)

- ^ Yan, Chongnian (2004). "国民—战犯—公民 (National - War criminal - Citizen)". 正说清朝十二帝 (True Stories of the Twelve Qing Emperors) (in Chinese). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. ISBN 710104445X.

- ^ Cao Kun (2005-10-06). "故宫X档案: 开院门票 掏五毛钱可劲逛 (Forbidden City X-Files: Opening admission 50 cents)". Beijing Legal Evening (in Chinese). People Net. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ^ a b Wen, Lianxi, ed. (1925). 故宫物品点查报告 [Palace items auditing report]. Beijing: Caretaker Committee of the Qing Dynasty Imperial Family. Reprint (2004): Xianzhuang Book Company. ISBN 7-80106-238-8.

- ^ Dorn, Frank (1970). The forbidden city: the biography of a palace. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 176. OCLC 101030.

- ^ See map of the evacuation routes at: "National Palace Museum – Tradition & Continuity". National Palace Museum. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ^ "National Palace Museum – Tradition & Continuity". National Palace Museum. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ^ a b c "三大院长南京说文物 (Three museum directors talk artifacts in Nanjing)". Jiangnan Times (in Chinese). People Net. 2003-10-19. Archived from the original on 2008-12-01. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ a b "北京故宫与台北故宫 谁的文物藏品多? (Beijing Palace Museum and Taipei Palace Museum: which collection is bigger?)". Guangming Daily (in Chinese). Xinhua Net. 2005-01-16. Archived from the original on 2009-01-10. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ Jackie Craven. "Forbidden City in Beijing, China". About.com: Architecture. Archived from the original on 2010-12-25. Retrieved 2010-05-06.

- ^ "Palace Museum puts its house in order". China Daily. Xinhua News Agency. 2011-01-27. Archived from the original on 2011-01-31. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ^ "Palace Museum discovers 55,000 items hidden within the Forbidden City – Life & Culture News – SINA English". english.sina.com. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ^ The Palace Museum. "Collection highlights – Paintings" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2007-07-01. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ Laufer, Berthold (1912). Jade: A Study in Chinese Archeology & Religion. Gloucestor MA: Reprint (1989): Peter Smith Pub Inc. ISBN 978-0-8446-5214-6.

- ^ The Palace Museum. "Collection highlights – Jade" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2007-07-01. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ The Palace Museum. "Collection highlights – Bronzeware" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2007-07-01. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ The Palace Museum. "Collection highlights – Timepieces" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2007-07-01. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ The Palace Museum. "Gilded copper clock with the decoration of writing person" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ The Palace Museum. "Collection highlights – Palace artifacts" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2007-07-01. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ^ "学术 – 故宫博物院". www.dpm.org.cn. Retrieved 2019-06-08.

- ^ 李雯蕊. "Palace Museum director Shan Jixiang retires – Chinadaily.com.cn". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- ^ "单霁翔". 故宫博物院. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ "New home for China's ancient treasures to display many more Palace Museum artefacts".

- ^ "Biography". Archived from the original on 14 August 2011.

- ^ "Turandot at the Forbidden City, Beijing 1998". Archived from the original on 2018-02-17. Retrieved 2007-05-01.; note some inconsistency in the description of the venue on the official site: it claims Archived 2016-04-25 at the Wayback Machine that the venue, the People's Cultural Palace, was the "Hall of Heavenly Purity". In fact, the Working People's Cultural Palace was the Temple to the Emperor's Ancestors= China.org: Working People's Cultural Palace Archived 2007-10-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Jean Michel Jarre lights up China". BBC. 2004-10-11. Retrieved 2007-05-01.