Operation Crazy Horse

| Operation Crazy Horse | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Vietnam War | |||||||

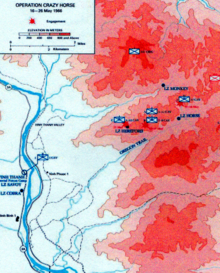

map of the Vinh Thanh valley and Operation Crazy Horse | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| unknown | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 missing[1] |

US body count: 478 killed[1] PAVN claim: 152 killed[3] | ||||||

Operation Crazy Horse (16 May to 5 June 1966), named after Lakota warrior Crazy Horse, was a search and destroy mission during the Vietnam War conducted by military forces of the United States, South Vietnam, and the Republic of South Korea in two valleys in Bình Định Province of South Vietnam.

The objective of the operation was to destroy the Viet Cong (VC) 2nd Regiment (approximately 2,000 men) believed to be in the area and thereby prevent an attack on the Vinh Thanh Civilian Irregular Defense Group camp. The U.S. forces had the continuing objective of protecting Highway 19 and the base camp of the 1st Cavalry Division at An Khe from harassment by the VC.

Background

In September 1965, the 1st Cavalry Division, newly arrived in South Vietnam, carved out Camp Radcliff, its base, near the town of An Khe to ensure that Highway 19 which reached from the coast of South Vietnam to the Central Highlands city of Pleiku remained under the control of allied forces. Almost immediately the 1st Cavalry began mounting operations against communist forces in the Vinh Thanh valley, 10 miles (16 km) northwest of An Khe. Vinh Thanh Valley was small, approximately 12 miles (19 km) long and less than 3 miles (4.8 km) wide, but heavily populated and dominated by the Viet Cong.[4]

10 miles (16 km) east of Vinh Thanh Valley was the Suoi Ca Valley. The two valleys were separated by a chain of heavily-forested mountains rising as much as 2,600 feet (790 m) over the river valleys. The soldiers dubbed Suoi Ca Valley "Happy Valley" (not to be confused with another American-named "Happy Valley" near the city of Danang). A trail crossing the mountains between the two valleys was named the "Oregon Trail." The U.S. estimated that a regiment of main force VC guerrillas controlled Suoi Ca Valley.

In late 1965, sweeps through the two valleys by the 1st Cavalry failed to find large numbers of VC. They were believed to have fled the valleys, but to have returned after the 1st Cavalry withdrew to its base.[4]

In early May 1966, Montagnard irregulars and U.S. Special Forces soldiers in the Vinh Thanh valley reported clashes and increased activity by the Viet Cong in the area and a possible major attack on 19 May, the birthday of North Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh. 1st Cavalry Division commander General John Norton ordered Operation Crazy Horse to preempt the attack and attempt to destroy the VC regiment believed to be in the area. Norton was prepared to dedicate up to five battalions of 1st Cavalry troopers to the task.[2]: 219–20

The operation

Phase One. The Americans began Operation Crazy Horse with heavy harassing artillery fire designed to disrupt a possible attack on the CIDG camp and to prepare for a helicopter landing. The initial helicopter landing was at Landing Zone Hereford on a ridge overlooking the Vinh Thanh valley and Special Forces camp three miles (5 km) distant.

Shortly after landing on May 16, Company B from the 2nd Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment became engaged with a VC battalion on a ridge near the landing zone. Because of bad weather, little air support was available to the Americans who were surrounded, during a break in the rain Company C 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry Regiment was landed and moved to support Company B. After an all-night fight at close quarters, the VC withdrew leaving behind 38 bodies and having killed 28 Americans.[5][2]: 220–1 Persuaded that they had located the VC regiment, Norton sent in two battalions on May 17 to find and pursue the VC. The 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry Regiment landed at Landing Zone Hereford while the 2/12th Cavalry touched down at Landing Zone Horse, in the mountains east of the Vinh Thanh Valley. The strategy was that the Americans would trap the VC between the two battalions, but, after initial firefights, the Americans searched eastward for several days mostly without success.[2]: 221–4

LZ Hereford. On 21 May, the situation at Landing Zone Hereford had been quiet for several days. Over the protests of the company commander, an under-strength weapons platoon of 20 soldiers was left alone at the landing zone while one company of the 1st Cavalry returned to An Khe and another departed the landing zone by foot on a search and destroy mission. Less than an hour after the platoon was left alone, the VC attacked with mortars followed by an infantry assault. Within the few minutes until reinforcements could arrive, 15 American soldiers and a journalist, Sam Castan, were killed. The VC retired uncontested from the area.[6][2]: 226

Phase Two. On May 24, in the wake of the VC attack at Landing Zone Hereford, General Norton changed strategies, called off search and destroy missions temporarily as he no longer wanted his soldiers "to go banging around in the enemy's backyard," and attempted instead to encircle the area where the VC were believed to be, cut off their escape routes, and called in artillery and airstrikes while Americans, South Korean, and South Vietnamese military units attempted to ambush VC units presumed to be fleeing the area. The peak allied strength devoted to Operation Crazy Horse was four American, one Vietnamese, one South Korean, and one CIDG (Montagnard with Special Forces advisers) battalions. One of the few significant clashes came on May 26 at Landing Zone Monkey where an American company was briefly under siege and a helicopter was shot down. By the end of May, it was apparent that most of the VC had escaped. Operation Crazy Horse was officially terminated on 5 June.[2]: 226–8

Assessment

Despite the failure by the Americans to engage the VC in large battles of attrition, the U.S. declared Operation Crazy Horse a success. The U.S. estimated that 507 VC had been killed at a loss of 83 Americans, 14 South Koreans, 8 South Vietnamese, and an unrecorded number of Montagnards. The operation also revealed, however, a limitation of airmobile warfare in heavily forested mountains. With only a few feasible places where helicopters could land, communist soldiers could anticipate likely landing sites and prepare to contest the landing or ambush the Americans as they fanned out from the landing zone.[2]: 227–8

Three months later the 1st Cavalry was back in Binh Dinh again with Operation Thayer to attempt once again to eliminate North Vietnamese and VC influence in the province.

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

- ^ a b Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015, 4th ed. Micheal Clodfelter. Micheal Clodfelter. ISBN 978-0-7864-7470-7. P. 676

- ^ a b c d e f g h Carland, John (2000). Combat Operations: Stemming the Tide, May 1965 to October 1966. United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 9781782663430.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "List of 3rd Division's KIA during the war". Archived from the original on 2022-10-07. Retrieved 2022-10-08.

- ^ a b "Publication, 1st Cavalry Division Association - Interim Report of Operations, First Cavalry Division, July 1965 to December 1966", ca. 1967, Folder 01, Box 01, Richard P. Carmody Collection". The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ Tolson, John F. (1999). Airmobility 1961-1971. Department of the Army. pp. 98–99.

- ^ Christy, Michael (2012),"Last Stand at Landing Zone Hereford", Vietnam, http://www.historynet.com/last-stand-at-lz-hereford.htm, accessed 1 May 2015