New London Union Station

New London, CT | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Front view of New London Union Station in July 2012 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | 35 Water Street New London, Connecticut United States | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owned by | New London RR Company (station)[1] Amtrak (track and platforms)[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line(s) | Amtrak Northeast Corridor[2] New England Central Railroad | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platforms | 1 side platform 1 island platform | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tracks | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Connections |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Construction | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parking | Yes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Accessible | Yes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station code | Amtrak: NLC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| IATA code | ZGD | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1848 (NLW&P) 1852 (NH&NL) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rebuilt | 1861(NLW&P) 1864 (NLN) 1886–1887 (Union Station) Renovations: 1976–77, 2002–03 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Passengers | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| FY 2023 | 154,876[3] (Amtrak) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2019 | 66 daily boardings[4] (Shore Line East) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Union Station | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 41°21′15″N 72°05′35″W / 41.35417°N 72.09306°W | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Architect | Henry Hobson Richardson[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NRHP reference No. | 71000913[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Added to NRHP | June 1971[5][6] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

New London Union Station is a railroad station on the Northeast Corridor located in downtown New London, Connecticut, United States. Union Station is a station stop for most Amtrak Northeast Regional trains and all CT Rail Shore Line East commuter rail trains, making it the primary railroad station in southeastern Connecticut. It serves as the centerpiece of the Regional Intermodal Transit Center, with connections to local and intercity buses as well as ferries to Long Island and Fishers Island, New York, and Block Island, Rhode Island. The station has one side platform and one island platform serving the two-track Northeast Corridor; the latter platform also serves a siding track that connects to the New England Central Railroad mainline.

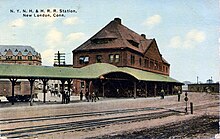

Rail service to New London began with the New London, Willimantic, and Palmer Railroad in 1848 and the New Haven and New London Railroad in 1852. The original stations were each replaced in the 1860s; after several consolidations, they were served by the Central Vermont Railway (CV) and New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad (New Haven) by the 1870s. After one of the stations burned in 1885, a new three-story brick union station was erected in 1887. It was the last and largest railroad station designed by famed architect H. H. Richardson, and his best according to biographer Henry-Russell Hitchcock.[7][8]

Passenger service declined in the 20th century; all CV passenger service to New London ended in 1949. The New London Redevelopment Agency began planning in 1961 to demolish the station as part of urban renewal. Amtrak took over passenger service in May 1971; Union Station was added to the National Register of Historic Places the next month following a local effort. After several years of controversy over whether to demolish or preserve the structure, it was purchased by architect George M. Notter in 1975. Notter's firm renovated the station for combined use by Amtrak and commercial tenants; it was the first station to be restored for Amtrak's use, and one of the earliest cases of adaptive reuse of an industrial-age building in New England.

Shore Line East commuter service joined Amtrak intercity service at the station in 1996. High-level platforms were added in 2001 to serve the new Acela Express service. A second renovation in 2002–03 restored the exterior and returned the waiting room to its original configuration. The planned National Coast Guard Museum, which will be located across the tracks from the station, will include a long-planned footbridge over the tracks.

History and design

Early stations

Union Station is the sixth railroad station to serve New London. When the New London, Willimantic, and Palmer Railroad opened in 1848, an existing building on Water Street a block east of Federal Street was converted into a station.[9][10] A two-story Greek Revival depot was built near the modern location in 1852 with the arrival of the New Haven and New London Railroad (NH&NL). The New London, Willimantic, and Palmer continued to use its older station for some time, although a track was built to join the two railroads.[10]

In 1854, a connecting track was opened through downtown Norwich, allowing trains from the Norwich and Worcester Railroad to connect with steamships at New London rather than Allyn's Point. Use of the connection stopped in November 1855, but was continuous after April 1859.[11] After the completion of the New London and Stonington Railroad to Groton Wharf in 1858, ferry service ran from New London to Groton to allow through railroad service.[11] The NH&NL station was soon too small to handle large passenger loads, and the Bureau of Railroad Commissioners was petitioned for a new station as early as 1859.[10]

The New Haven and New London Railroad merged with the New London and Stonington in 1857 to form the New Haven, New London and Stonington Railroad. The line was leased by the New York, Providence and Boston Railroad (NYP&B) in 1859. The NYP&B bought the section east of Groton outright in 1864; the section from New London westward was spun off as the Shore Line Railway. In 1870, the Shore Line was leased by the New York and New Haven Railroad, which itself became part of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad in 1872.[11] At some point during this series of events, the 1852-built station was replaced by a larger, two-story structure, which was also used by some through trains from the north.[10]

In 1861, the New London Northern Railroad succeeded the New London, Willimantic, and Palmer.[11] That year, the railroad constructed a freight depot and steamboat wharf (likely also used for passenger trains) along Water Street. The depot burned on May 8, 1864, but was rebuilt on the same site.[10]

The NYP&B-era station was highly unpopular; the Bureau was petitioned for a replacement not long after it was built, and local newspapers took up the issue in 1874 and 1875. In 1877, the commissioners referred to the "wholly insufficient and inconvenient accommodations" at the station. When the building burned on February 5, 1885, one newspaper remarked "few New London people are sorry, as the ancient structure had long since outlived its usefulness." It was torn down in April 1886.[10]

H.H. Richardson station

After the previous depot was destroyed, the Central Vermont Railroad (which then leased the New London Northern) began making plans for a larger replacement station. The Central Vermont and the New Haven Railroad (which had bought the Shore Line in 1870) bought the east end of the Parade from New London for the unusually low price of $15,000, with the understanding that the railroads would build a structure more suitable for the bustling city.[12]

Noted American architect Henry Hobson Richardson, known for his public buildings including several Boston and Albany Railroad depots, was hired by the Central Vermont in September 1885 to design the new station. Richardson likely obtained the commission through his friend and former classmate James A. Rumrill, who was a director of the railroad.[13] New London was the last of many railroad stations worked on by Richardson before his death in 1886, though numerous others were designed by his students (including the nearby New London Public Library designed by Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge). Many of Richardson's later attributed works were designed primarily by his office staff, but the quality of the design indicates that it was closely supervised by Richardson.[8] Richardson's biographer, Henry-Russell Hitchcock, considered New London to be his best station design.[8]

Union Station is particularly large for a Richardson train station, and stands out as the only of his stations not built in the Richardsonian Romanesque style of Trinity Church in Boston. Instead, it is a "severe, compact brick box", with significant Colonial influence taken from other buildings in New London.[9][14] Its design is heavily based on Sever Hall at Harvard University, which Richardson designed in 1878. The station has a similar profile, brick color and patterns, and arched entryway, but lacks the ornamentation of Sever.[8][13] Richardson originally designed Union Station with rough stone walls and Longmeadow trim like his other stations, but the material was changed to less expensive brick shortly before construction; the ornamentation was also likely eliminated at this time.[7] The strict symmetry is atypical of Richardson's designs and may have been a later change by Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge after Richardson's death.[7]

Although different from his other stations, the 2+1⁄2-story structure features many of Richardson's characteristic motifs, including its multi-faceted roof, prominent arched entrance, and elegant brickwork.[15] Like many of his stations, the roofline is dominant and contrasts the monochrome walls. The bricks are arranged in a mixture of Flemish bond and two different herringbone styles, broken by details around windows and doors, to create visual interest.[2] A projecting central section tempers the roofline on the east and west facades, while the dormers shown a slight Asian influence common in his designs. The rear bay window – the lone circular element save for the matching arched front doorway – served as the ticket booth.[2] The ceiling and third floor are suspended from the roof trusses using an array of 2-inch (51 mm)-diameter iron rods, which allowed for a large two-story waiting room without interior columns.[14] The platform canopy was notable for matching the broad curve of the tracks; it originally extended further south, with a raised "eyebrow" section over State Street.[9]

The new station began construction in September 1886 and opened in 1887, with a total cost of $76,300.[13] It was designated a union station as it connected two railroads – the Central Vermont Railroad which succeeded the New London, Willimantic, and Palmer, and the Shore Line which would merge into the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad in 1897. The Thames River Bridge was opened in October 1889, connecting the station to the New York, Providence and Boston Railroad and completing the Shore Line rail link from New York to Boston. The southern end of the Norwich and Worcester Railroad was completed through Gales Ferry in June 1899, allowing traffic from Worcester to reach New London via the bridge rather than through Norwich.[11]

Around 1912, New London citizens successfully petitioned the Public Utilities Commission for the installation of a footbridge connecting the station to the ferry docks in order to improve pedestrian safety. At the time, with no bridge crossing the river below Norwich, the ferries were heavily used. The footbridge, constructed of steel with a canopy to keep out rain, was constructed soon after.[16]

Decline and revival

Central Vermont passenger service running north ended in 1949, but service running east and west along the Shore Line has remained continuous since the station was built.[11] In the latter days of the New Haven Railroad, infrastructure was not maintained in order to cut costs, and stations like New London suffered for it. In 1953, the railroad asked the Public Utilities Commission for permission to remove the footbridge, but the request was denied. The railroad petitioned again in 1961, seeking to spend $1,250 to remove the bridge rather than $15,000 repairing it. Of the average 132 people using the bridge daily (versus 612 crossing the tracks on the street), most were reportedly using it as an "observation post" to view the harbor.[16][17] In 1955, architect Marcel Breuer designed new stations at Rye and New London for the New Haven Railroad as part of a design program overseen by Knoll Associates. Neither new station was ultimately built.[18]

In 1961, the New London Redevelopment Agency called for the station to be demolished to make room for a shopping mall or department store as an "urban renewal" project. This began a fifteen-year fight over the station building, pitting the Redevelopment Agency against a small group of private citizens who wished to have the building restored for further use.[19] The city paid $120,000 to buy the station; demolition costs were estimated at $55,000.[20] The New Haven Railroad folded into Penn Central in 1969; continually beset with financial problems, Penn Central had no interest in investing in the station.[20] The station by this time was "a dust-covered derelict with urine-soaked floors and peeling ceilings."[19] Amtrak took over intercity passenger service on May 1, 1971; Penn Central continued to operate a limited amount of local service that was discontinued over the rest of the decade.[21] After a local effort, Union Station was added to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in June 1971 over the lobbying efforts of former mayor Richard Martin. Martin claimed that ninety percent of the city agreed with the redevelopment plans. Under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the addition to the NRHP prevented local authorities from using federal funds for demolition, although the law did not provide for enforcement or punishment.[6][20]

The conflict was generally seen locally as outside "meddlers" – state officials, rich "out-of-state bleeding hearts", and historians – interfering with local plans that would improve the city. Robert P. Turk, director of the Redevelopment Agency, wrote a letter accusing preservationists of dealing in "pure academic nonsense".[22] Frank Scheetz, a Groton local and former submariner, attempted to buy the station for use as a submarine museum, with plans to berth a decommissioned submarine nearby.[6] The Redevelopment Agency rejected Scheetz's offer, claiming he was a speculator; Scheetz alleged that the city duplicitously changed prices in order to refuse the legitimate offer.[20] (Scheetz later funded the display of the USS Croaker in Groton from 1977 to 1987, and was "instrumental" in bringing the USS Nautilus to permanent display at Submarine Force Library and Museum at the Naval Submarine Base New London in the 1980s.)[23] In September 1973, the City Council voted to allow demolition. Amtrak responded with a letter stating that the company wanted to discuss the possibility of preservation and would be willing to contribute financially.[6] That year, a number of the same local activists formed the Union Railroad Station Trust, intending to restore the station.[2]

On February 20, 1975, the Redevelopment Agency voted to demolish the building.[24] Union Railroad Station Trust asked the Boston architectural firm Anderson Notter Associates to prepare a study of adding office and restaurant space.[25] George M. Notter, one of the firm's principals (and later president of the American Institute of Architects), was an early advocate of adaptive reuse.[2][26] Surprised that no developers were pursuing what he saw as a sure profit, Notter formed Union Station Associates as a subsidiary of Anderson Notter and invested a substantial sum of his own money into the station. Notter convinced Amtrak to agree to a 20-year lease for part of the station at $45,000 annually, thus giving the group a stronger negotiating point.[19][27] After eighteen months of negotiations, Union Station Associates purchased the building on July 24, 1975, effectively saving the station.[25][28] The group paid only the cost of the underlying land, $11,400 – the same figure Scheetz initially offered two years before.[19][20]

Union Station Associates spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on a full renovation of the building for combined use by Amtrak and commercial tenants.[19] The exterior was restored to the original 1885 specifications.[15] However, some of the interior work modified the station far from its original configuration. A mezzanine was built over half the waiting area to provide restaurant seating, and the floor of the rest was cut out to create an atrium. The basement became the passenger waiting area, with a newsstand and a plant shop occupying additional space.[27][29] New, wider platforms were built to improve the boarding experience.[9] The renovated station was celebrated and rededicated in July 1976.[19] The New London Day, which five years before called the station an "eyesore", ran their coverage under the headline "We were wrong!"[25] New London Union Station was the first station in the country to be restored for Amtrak use.[15] It represented a "watershed" in historic preservation as one of the first industrial age structures in New England to be reused – a shift away from the previous attitude that valued only Colonial buildings – as well as the recognition of the historic value of the old downtowns of New England's port cities.[25]

Turn of the century

As Notter predicted, the renovated station initially proved attractive to commercial tenants. When an engineering firm moved into the "Crow's Nest" of the attic space in the late 1980s, the building was fully occupied for the first time since the heyday of the New Haven railroad.[14] However, Notter and others involved in the 1975 purchase were approaching retirement age. In the late 1990s, the city offered to buy the station for use as a maritime museum detailing the history of the adjacent Thames River. No longer worried about the safety of the building, the developers sold, and the tenants moved elsewhere.[14]

In 1996, the well-connected owners of Cross Sound Ferry proposed a footbridge from the Water Street parking garage to the ferry slips so that ferry passengers would not have to cross Water Street and the tracks at grade. Amtrak saw the project as an opportunity to build a new elevated station nearby and contributed $1 million to the design of the bridge. However, Amtrak reversed course in 1999 and decided to keep using Union Station; in 2001, the railroad declined to fund the footbridge.[30] Also in 2001, Amtrak built a pair of high-level platforms to serve the new Acela high-speed service, thus adapting the 19th-century station for 21st-century usage. Catenary wires were installed over the tracks as part of the introduction of the Acela.[31][32] Late that year or early in 2002, the 1899-built freight house on the east side of the tracks was torn down as part of redevelopment sponsored by the New London Development Corporation. The freight house had previously been used by Amtrak maintenance-of-way crews, and before that by the Fishers Island Ferry District.[9]

By this time, many of the 1970s repairs were beginning to wear down, and the city put aside its plans for the maritime museum.[14] The New London Railroad Company, fronted by historian Barbara Timken and local businessman Todd O'Donnell, bought the station from the city as the New London Railroad Company in 2002. The pair organized a second full restoration of the station, including a new slate roof, restored brickwork, and restoration of the waiting room to its original configuration.[2] The mezzanine level and basement atrium created in the 1976 renovation were removed.[14] Additionally, mechanical systems were upgraded and various accessibility concerns addressed. The baggage room was restored for Greyhound use.[29] Amtrak and Greyhound rent space from the company for offices and passenger waiting areas.[33]

Despite Amtrak's disinterest in the project, Cross Sound continued to pursue construction of the footbridge. Standing as high as 73 feet (22 m) (higher than the station itself), the bridge was to cost $10 million, paid by public funds.[30] In 2003, the city used eminent domain to take portions of the station property in order to build a footbridge from the Water Street parking garage to the ferry slips on the east side of the tracks. The city only wished to pay for the small area taken up by the footprints, but O'Donnell wanted more compensation because the large footbridge would detract from the aesthetics of the historic station. With no agreement reached, the issue went to court.[14] Meanwhile, O'Donnell was in a financial conundrum: the taxi and auto traffic generated by the bus, rail, and ferry traffic was limiting his ability to lease space in the station. He abandoned renovations to the upper floors, and was forced to consider ending the leases with Amtrak and Greyhound and seek alternate tenants.[14][34] In 2007, the city abandoned the eminent domain case and scrapped the footbridge plans, although O'Donnell was still considering selling the building.[14]

Shore Line East

In February 1996, a single Shore Line East weekday round trip was extended from Old Saybrook to New London. An additional round trip was extended in February 2010, and 3 more in May 2010 for a total of 5 daily round trips between New London and New Haven.[35] Weekend Shore Line East service between Old Saybrook and New Haven Union Station began in 2008, but no regular weekend trains ran to New London.[36]

In July 2012, Governor Dannel Malloy announced that 5 weekend round trips would be extended to New London beginning in April 2013. However, the extension was dependent on ongoing negotiations with the marine industry over mandated closings of the Old Saybrook – Old Lyme bridge.[37] Two weekday midday trips were added in May 2013, while weekend service began on June 1, 2013, after the application for additional bridge closings was approved by the state Department of Energy and Environmental Protection.[38][39] Because Shore Line East service to New London is limited, Amtrak honors monthly Shore Line East passes on select intercity trains between New London and New Haven.[40] By 2019, weekend Shore Line East ridership at New London was nearly twice weekday ridership.[4]

Upgrades and Coast Guard Museum

In 2006, the Southeastern Connecticut Council of Governments (SCCOG) began a study of how to improve the Regional Intermodal Transportation Center (RITC), including Union Station.[14] The study analyzed problems with the RITC – including poor pedestrian connections, minimal bus facilities, and a lack of food vendors – and considered but rejected a move to a Fort Trumbull site. The proposed alternative released in 2010, which would cost around $20 million, would relocate Water Street slightly to the west. The bus terminal would be expanded, with a new building adding onto the existing former baggage office. A pedestrian bridge was to be constructed connecting the Water Street Garage, the main station area, the northbound Amtrak platform, and the ferry terminal – a design that served station passengers as well as the ferries. Other pedestrian improvements were to include wayfinding signs, pedestrian-scale lighting, and expanded sidewalks.[33]

Beginning in 2010, Union Station was considered a possible site for the National Coast Guard Museum, which would have added a glass atrium north of the main station building as well as a pedestrian bridge over the tracks to a second waterfront building. The Coast Guard removed the site from consideration in May 2012 due to opposition from Cross Sound Ferry over use of its property. The station's private owners stated that they would consider other uses for the space.[41]

However, after further consideration, the Coast Guard announced in April 2013 that the museum was to be located at Union Station.[42] The main portion of the museum is to be located east of the tracks, with a new 500-passenger ferry terminal likely integrated into the four-story, 54,300-square-foot glass-faced building.[43] A pedestrian bridge will connect the museum to the station and the northbound platform, as well as to the Water Street garage.[44]

In July 2013, the station owners sent a letter of concern to the state, seeking that the Environmental Impact Report for the museum and footbridge consider a breadth of possible impacts, particularly from the footbridge.[45] The museum itself received a Finding Of No Significant Impact in March 2014. The Environmental Impact Evaluation for the footbridge, released in July 2014, analyzed seven alternatives for the footbridge location. Alternative 5a, located east of the baggage building and including a section to the garage, was the preferred alternative.[44] The state committed $20 million towards the cost of the potential footbridge.[46]

In 2014, O'Donnell and Timken began talks with the Coast Guard Museum Association about selling the station to a third-party investor associated with the Association.[46] The sale was originally to be effective at the end of 2014, but was delayed because the Redevelopment Agency never issued a formal certificate of completion for the 1975 sale and renovations. Since the Agency was dissolved in 2008, the City Council issued the certificate in early January 2015, allowing the sale to proceed.[47] On January 12, the Council released the station from the 1960s urban renewal plan as part of an agreement with O'Donnell and Timken to ease the sale process. The new agreement also included stipulations for historic preservation of the building, and allowed – but did not require – its continued use as a train station.[48] On January 29, 2015, Union Station Development sold the station to the New London RR Company – a holding company owned by James Coleman Jr., chairman of the Association – for $3 million.[1][49] Coleman brought in a restaurant serving locally sourced food for the first floor, and intended to renovate the second floor for use by museum-related tenants.[50]

Electrification and track work on Track 6, necessary to allow use of M8 electric railcars on Shore Line East, took place from November 2021 to April 2022.[51] The cars entered service for Shore Line East that May.[52][53] In June 2023, the US Department of Transportation awarded $17 million for transportation improvements in downtown New London, including the footbridge and station renovations.[54]

Layout

New London Union Station | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

New London has an unconventional platform layout due to the State Street grade crossing and its location on a sharp curve. The two Northeast Corridor tracks (Tracks 1 and 2) are next to the station, while the New England Central Railroad (formerly Central Vermont) freight track (Track 6) is further away.[31][55]

Both NEC tracks have high-level platforms, which were added in 2001 for use by Acela trains, which cannot use low platforms.[31] The southbound NEC track is served by a low platform behind the station, which leads to a short high-level platform south of State Street. The northbound NEC track is served by a high-level platform behind the station building; the low platform south of State Street is generally only used for deboarding passengers from busy trains.[31] Because of the sharp curve, the high-level platforms are set slightly back from the tracks to avoid scraping the ends of train cars, and thus bridge plates are needed to span the gap between platform and car.[56]

The northbound platform, currently a side platform, can serve as an island platform should passenger service return to the NECR track. The 2010 SCCOG report indicated that Amtrak wished Shore Line East to move its operations to Track 6, freeing the mainline tracks for through trains.[33] In 2013, most Shore Line East trains began using Track 6. Most passengers use the low-level section of the platform south of State Street, but a short metal spur on the high-level platform provides handicapped accessible boarding for trains using the track.[31] A low-level section of the northbound platform also remains north of the high-level section; it has not been used since the high-level section was constructed.

The southbound platform is adjacent to the station building, and its high-level section requires crossing only a lightly used spur of State Street. However, access to the northbound platform requires crossing both Northeast Corridor tracks. The footbridge to the planned Coast Guard Museum will allow access to the northbound platform without crossing tracks, which will improve safety and prevent passengers from being trapped on the platform by stopped trains.[33]

Service

Most Amtrak Northeast Regional trains that run on the Northeast Corridor east of New Haven (about 9 trains each direction daily) stop at New London.

The station was previously also served by a small number of Acela trains: one southbound train in the morning, and northbound trains in the morning and evening. When Acela trains served the station, most ran nonstop between Providence and New Haven.[57] Acela service was discontinued by 2022.[58]

Shore Line East service to New London is limited by slots available over the Connecticut River bridge between Old Saybrook and Old Lyme; service is operated at uneven headways on weekdays and weekends. Multi-ride and monthly Shore Line East tickets are accepted on several Northeast Regional trains as well.[59]

The Central Corridor Rail Line is a proposed regional service which would run from New London north through Norwich, Willimantic, and Amherst to Brattleboro, Vermont over the New England Central Railroad. While locally supported by some towns along the route, the service is not currently funded.[60]

Intermodal connections

Several ferry services run from docks on Ferry Street just north of the station. The Cross Sound Ferry runs to Orient Point on Long Island with approximately hourly service year-round. The Block Island Fast Ferry, a high-speed catamaran to Block Island, runs several daily round trips during the summer months. The Fishers Island Ferry offers year-round local service to Fisher's Island, about 5 miles offshore, with multiple daily trips.[2]

Greyhound Bus Lines offers limited intercity service from a stop on Water Street. Current service consists of two daily buses in each direction operating along the I-95 corridor, with transfers available to other routes in Boston, New Haven, and New York City. Greyhound and Peter Pan Bus (which no longer serves New London) previously used the former baggage and express office.[9][33]

Union Station is one of four major transfer points for Southeast Area Transit (SEAT) local bus service, with timed connections on a clock-face schedule between several routes running from New London to nearby areas including Norwich, Groton, Niantic, Waterford, and Foxwoods Casino. SEAT buses serving the station stop at a shelter north of the station building on Water Street.[33] The following SEAT routes run from Union Station:

- 1 Norwich / Mohegan Sun / New London – Route 32

- 2 Norwich / Groton/ New London – Route 12

- 3 Groton / New London / Niantic

- 12 Jefferson Avenue / Crystal Mall / New London Shopping Center / Senior Center

- 13 Shaws Cove / L & M Hospital / Ocean Beach

- 14 New London Mall / Waterford Commons / Crystal Mall / New London Shopping Center

- 15 New London / Waterford – Evening Service

- 108 New London / Groton / Mistick Village / Foxwoods

Union Station is also served by 9 Town Transit route 643. The drop-off lane in front of the station also serves as a taxi stand for several local companies. Special buses to Foxwoods Casino, which connect primarily to Cross Sound Ferry services, also stop nearby.[33]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Warranty Deed" (PDF). New London RR CO. January 28, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "NEW LONDON, CT (NLC)". Great American Stations. Amtrak. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ "Amtrak Fact Sheet, Fiscal Year 2023: State of Connecticut" (PDF). Amtrak. March 2024. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ a b "Attachment 8: Shore Line East station ridership" (PDF). Facility Management Services for Various Railroad Station Facilities for Region C. Connecticut Department of Transportation. 2021.

- ^ a b c "Connecticut – New London County". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ^ a b c d "Amtrak Urges the Preservation Of Periled New London Station". The New York Times. September 23, 1973. p. 29 – via Proquest Historical Newspapers.

- ^ a b c Floyd, Margaret Henderson (1997). Henry Hobson Richardson: A Genius for Architecture. Monacelli Press. pp. 200, 218. ISBN 1885254709.

- ^ a b c d Hitchcock, Henry-Russell (1961). The Architecture of H. H. Richardson and His Times (revised ed.). Archon Books. pp. 273, 278. ISBN 9780262580052.

- ^ a b c d e f Roy, John H. Jr. (2007). A Field Guide to Southern New England Railroad Depots and Freight Houses. Branch Line Press. pp. 72–74. ISBN 9780942147087.

- ^ a b c d e f Belletzkie, Bob. "CT Passenger Stations, N-NE". TylerCityStation. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Karr, Ronald Dale (1995). The Rail Lines of Southern New England. Branch Line Press. p. 107. ISBN 0942147022.

- ^ "The Parade a Conspicuous Feature". The New London Day. July 2, 1931. Archived from the original on November 17, 2010 – via New London Landmarks.

- ^ a b c Ochsner, Jeffery Karl (1982). H.H. Richardson: Complete Architectural Works. MIT Press. pp. 403–406. ISBN 0262150239.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Dilts, James D. (Fall–Winter 2010). "Three Amtrak Stations Take Different Roads to Rehabilitation". Railroad History (203): 46–50. JSTOR 43525153.

- ^ a b c McDonald, Melissa (June 7, 1983). "Photographs: Written Historical and Descriptive Data" (PDF). Historic American Buildings Survey. United States National Park Service.

- ^ a b "State Gives Its Permission To Raze Railroad Footbridge". The New London Day. September 9, 1961 – via Google Newspapers.

- ^ "New London, Conn., railroad station". Leroy Roberts Railroad Collection. September 14, 1958. Archived from the original on June 23, 2010.

- ^ Frattasio, Marc J. (2023). "Marcel Breuer's Forgotten Articulated Commuter Car Project". Shoreliner. Vol. 44, no. 4. pp. 28–39.

- ^ a b c d e f Knight, Michael (July 23, 1976). "New London Station Restored by Amtrak". New York Times. p. 19. ProQuest 122879078.

- ^ a b c d e Knight, Michael (September 28, 1973). "Station (Landmark or Eyesore) Nears End". The New York Times. p. 35. ProQuest 119793625.

- ^ Baer, Christopher T. (April 2015). "A GENERAL CHRONOLOGY OF THE SUCCESSORS OF THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD COMPANY AND THEIR HISTORICAL CONTEXT: 1971" (PDF). Pennsylvania Railroad Technical and Historical Society.

- ^ Huxtable, Ada Louise (May 9, 1971). "A Lot Happens In Ten Years". The New York Times. ProQuest 119093677.

- ^ "Frank Scheetz dies; contractor, veteran led fight to return Nautilus to Groton". The New London Day. June 4, 1998. p. B1 – via Google Newspapers.

- ^ Baer, Christopher T. (April 2015). "PRR CHRONOLOGY: 1975" (PDF). Pennsylvania Technical and Historical Society. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Campbell, Robert (November 21, 1976). "Union Station: It's more than just a renovation". Boston Globe. p. E3. ProQuest 747838300.

- ^ Sullivan, Patricia (December 28, 2007). "George Notter, 74; Architect Remade Old Buildings (obituary)". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ^ a b "New life for old station". Boston Globe. September 5, 1976. p. E3. ProQuest 747472297.

- ^ "Special City Council Meeting Agenda" (PDF). City of New London. January 9, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 11, 2016. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^ a b "Union Railroad Station: New London's Gem". Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on March 12, 2013. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ^ a b Condon, Tom (January 16, 2005). "Skywalk Is Not The Ticket For New London". Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Cox, Jeremiah (December 24, 2014). "New London, CT". Subway Nut. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- ^ "Acela Express Startup Scheduled—Again" (PDF). TrainRider. Vol. 10, no. 3. Train Riders/Northeast. Fall 2000. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g TranSystems (March 2010). "Regional Intermodal Transportation Center Master Plan and Efficiency Study: Executive Summary" (PDF). Southeastern Connecticut Council of Governments. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ Holtz, Jeff (August 27, 2006). "A Station Unsure Where It's Headed". New York Times. p. P2. ProQuest 93090047.

- ^ "All aboard the Shore Line East!". The New London Day. May 9, 2010. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ "Governor Rell Announces Weekend Shore Line East Rail Service Starting on 4th of July" (Press release). Connecticut Department of Transportation. June 27, 2008.

- ^ "Shore Line East Steaming Into New London". Hartford Courant. July 6, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ Smith, Greg (May 17, 2013). "Shore Line East expands train service". The New London Day. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- ^ Altimari, Daniela (May 30, 2013). "Shore Line East Adding Weekend Service". Hartford Courant. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Drelich, Kimberly (July 10, 2015). "Commuters, officials cheer Amtrak honoring Shore Line East tickets". The New London Day. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ Langevald, Dirk (May 3, 2012). "Coast Guard Passes On Union Station As Museum Site". New London Patch. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Kathleen Edgecomb and Jennifer McDermott (April 5, 2013). "Great expectations for New London come with national museum". The New London Day. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ Petrone, Paul (April 5, 2013). "A National Coast Guard Museum For Downtown New London". Waterford Patch. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ a b Milone & MacBroom, INC (July 2014). "ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT EVALUATION: NATIONAL COAST GUARD MUSEUM PEDESTRIAN OVERPASS, NEW LONDON, CONNECTICUT" (PDF). State of Connecticut Department of Economic & Community Development.

- ^ Timken, Barbara; O'Donnell, Todd; Quinn, Daniel (July 17, 2003). "Re: Request for Scoping Determination, CEPA Scoping Notice, June 4, 2013, U.S. National Coast Guard Museum" (PDF). GreenbergTraurig. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 10, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- ^ a b Bergman, Julia (December 14, 2014). "Sale of Union Station is near on behalf of Coast Guard Museum group". The New London Day. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- ^ Bergman, Julia (January 6, 2015). "Sale of Union Station delayed by lack of document". The New London Day. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- ^ Young, Colin A.; Bergman, Julia (January 13, 2015). "New London's Union Station sale takes step forward". The New London Day. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- ^ Bergman, Julia (January 30, 2015). "Coast Guard museum project may be picking up steam". The New London Day. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- ^ Bergman, Julia (July 10, 2016). "Union Station owner in town to check on progress". The New London Day. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ "Project Information Appendix". Northeast Corridor Capital Investment Plan: Fiscal Years 2022-2026 (PDF). Northeast Corridor Commission. October 2021. p. A3-46.

- ^ "Governor Lamont Announces That M8 Electric Trains Have Arrived on Shore Line East". Office of the Governor of Connecticut (Press release). May 24, 2022.

- ^ Hartley, Scott A. (May 24, 2022). "Connecticut replaces diesel Shore Line East trains with electric multiple-unit equipment". Trains Magazine. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ "RAISE 2023 Fact Sheets" (PDF). United States Department of Transportation. June 2023. p. 29.

- ^ TranSystems (November 2010). "Analysis of Costs for the Operation and Maintenance of the Transportation Related Areas of New London Union Station, the Adjacent Greyhound Facility and the Water Street Parking Garage" (PDF). Regional Intermodal Transportation Center Master Plan and Efficiency Study. Southeastern Connecticut Council of Governments. pp. 9–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 10, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

- ^ "Northeast Corridor Employee Timetable #5" (PDF). Amtrak. October 6, 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2016 – via National Transportation Safety Board.

- ^ "Northeast Corridor Timetable" (PDF). Amtrak. March 10, 2018. Retrieved June 3, 2018.

- ^ "Acela Train". Retrieved April 10, 2022.

- ^ "Expanding Rail Service" (PDF). Connecticut Department of Transportation. January 1, 2007.

- ^ Benson, Adam (February 21, 2014). "Rail line plan to seek federal funding". Norwich Bulletin. Retrieved August 30, 2016.

External links

- New London, CT – Amtrak

- New London, CT – Station history at Great American Stations (Amtrak)

- Shore Line East – New London, CT

- Station Building on Google Maps Street View

- Historic American Engineering Record entry and images for New London Union Station

- "The Rescue of Mr. Richardson's last station", a video recording of a movie that documents the efforts in the late 1970s to save the station