Nanocrystalline material

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Nanomaterials |

|---|

|

| Carbon nanotubes |

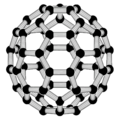

| Fullerenes |

| Other nanoparticles |

| Nanostructured materials |

A nanocrystalline (NC) material is a polycrystalline material with a crystallite size of only a few nanometers. These materials fill the gap between amorphous materials without any long range order and conventional coarse-grained materials. Definitions vary, but nanocrystalline material is commonly defined as a crystallite (grain) size below 100 nm. Grain sizes from 100 to 500 nm are typically considered "ultrafine" grains.

The grain size of a NC sample can be estimated using x-ray diffraction. In materials with very small grain sizes, the diffraction peaks will be broadened. This broadening can be related to a crystallite size using the Scherrer equation (applicable up to ~50 nm), a Williamson-Hall plot,[1] or more sophisticated methods such as the Warren-Averbach method or computer modeling of the diffraction pattern. The crystallite size can be measured directly using transmission electron microscopy.[1]

Synthesis

Nanocrystalline materials can be prepared in several ways. Methods are typically categorized based on the phase of matter the material transitions through before forming the nanocrystalline final product.

Solid-state processing

Solid-state processes do not involve melting or evaporating the material and are typically done at relatively low temperatures. Examples of solid state processes include mechanical alloying using a high-energy ball mill and certain types of severe plastic deformation processes.

Liquid processing

Nanocrystalline metals can be produced by rapid solidification from the liquid using a process such as melt spinning. This often produces an amorphous metal, which can be transformed into an nanocrystalline metal by annealing above the crystallization temperature.

Vapor-phase processing

Thin films of nanocrystalline materials can be produced using vapor deposition processes such as MOCVD.[2]

Solution processing

Some metals, particularly nickel and nickel alloys, can be made into nanocrystalline foils using electrodeposition.[3]

Mechanical properties

Nanocrystalline materials show exceptional mechanical properties relative to their coarse-grained varieties. Because the volume fraction of grain boundaries in nanocrystalline materials can be as large as 30%,[4] the mechanical properties of nanocrystalline materials are significantly influenced by this amorphous grain boundary phase. For example, the elastic modulus has been shown to decrease by 30% for nanocrystalline metals and more than 50% for nanocrystalline ionic materials.[5] This is because the amorphous grain boundary regions are less dense than the crystalline grains, and thus have a larger volume per atom, . Assuming the interatomic potential, , is the same within the grain boundaries as in the bulk grains, the elastic modulus, , will be smaller in the grain boundary regions than in the bulk grains. Thus, via the rule of mixtures, a nanocrystalline material will have a lower elastic modulus than its bulk crystalline form.

Nanocrystalline metals

The exceptional yield strength of nanocrystalline metals is due to grain boundary strengthening, as grain boundaries are extremely effective at blocking the motion of dislocations. Yielding occurs when the stress due to dislocation pileup at a grain boundary becomes sufficient to activate slip of dislocations in the adjacent grain. This critical stress increases as the grain size decreases, and these physics are empirically captured by the Hall-Petch relationship,

where is the yield stress, is a material-specific constant that accounts for the effects of all other strengthening mechanisms, is a material-specific constant that describes the magnitude of the metal's response to grain size strengthening, and is the average grain size.[6] Additionally, because nanocrystalline grains are too small to contain a significant number of dislocations, nanocrystalline metals undergo negligible amounts of strain-hardening,[5] and nanocrystalline materials can thus be assumed to behave with perfect plasticity.

As the grain size continues to decrease, a critical grain size is reached at which intergranular deformation, i.e. grain boundary sliding, becomes more energetically favorable than intragranular dislocation motion. Below this critical grain size, often referred to as the “reverse” or “inverse” Hall-Petch regime, any further decrease in the grain size weakens the material because an increase in grain boundary area results in increased grain boundary sliding. Chandross & Argibay modeled grain boundary sliding as viscous flow and related the yield strength of the material in this regime to material properties as

where is the enthalpy of fusion, is the atomic volume in the amorphous phase, is the melting temperature, and is the volume fraction of material in the grains vs the grain boundaries, given by , where is the grain boundary thickness and typically on the order of 1 nm. The maximum strength of a metal is given by the intersection of this line with the Hall-Petch relationship, which typically occurs around a grain size of = 10 nm for BCC and FCC metals.[4]

Due to the large amount of interfacial energy associated with a large volume fraction of grain boundaries, nanocrystalline metals are thermally unstable. In nanocrystalline samples of low-melting point metals (i.e. aluminum, tin, and lead), the grain size of the samples was observed to double from 10 to 20 nm after 24 hours of exposure to ambient temperatures.[5] Although materials with higher melting points are more stable at room temperatures, consolidating nanocrystalline feedstock into a macroscopic component often requires exposing the material to elevated temperatures for extended periods of time, which will result in coarsening of the nanocrystalline microstructure. Thus, thermally stable nanocrystalline alloys are of considerable engineering interest. Experiments have shown that traditional microstructural stabilization techniques such as grain boundary pinning via solute segregation or increasing solute concentrations have proven successful in some alloy systems, such as Pd-Zr and Ni-W.[7]

Nanocrystalline ceramics

While the mechanical behavior of ceramics is often dominated by flaws, i.e. porosity, instead of grain size, grain-size strengthening is also observed in high-density ceramic specimens.[8] Additionally, nanocrystalline ceramics have been shown to sinter more rapidly than bulk ceramics, leading to higher densities and improved mechanical properties,[5] although extended exposure to the high pressures and elevated temperatures required to sinter the part to full density can result in coarsening of the nanostructure.

The large volume fraction of grain boundaries associated with nanocrystalline materials causes interesting behavior in ceramic systems, such as superplasticity in otherwise brittle ceramics. The large volume fraction of grain boundaries allows for a significant diffusional flow of atoms via Coble creep, analogous to the grain boundary sliding deformation mechanism in nanocrystalline metals. Because the diffusional creep rate scales as and linearly with the grain boundary diffusivity, refining the grain size from 10 μm to 10 nm can increase the diffusional creep rate by approximately 11 orders of magnitude. This superplasticity could prove invaluable for the processing of ceramic components, as the material may be converted back into a conventional, coarse-grained material via additional thermal treatment after forming.[5]

Processing

While the synthesis of nanocrystalline feedstocks in the form of foils, powders, and wires is relatively straightforward, the tendency of nanocrystalline feedstocks to coarsen upon extended exposure to elevated temperatures means that low-temperature and rapid densification techniques are necessary to consolidate these feedstocks into bulk components. A variety of techniques show potential in this respect, such as spark plasma sintering[9] or ultrasonic additive manufacturing,[10] although the synthesis of bulk nanocrystalline components on a commercial scale remains untenable.

See also

References

- A. Inoue; K. Hashimoto, eds. (2001). Amorphous and nanocrystalline materials : preparation, properties, and applications. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3540672710.

- ^ a b Anandkumar, Mariappan; Bhattacharya, Saswata; Deshpande, Atul Suresh (2019-08-23). "Low temperature synthesis and characterization of single phase multi-component fluorite oxide nanoparticle sols". RSC Advances. 9 (46): 26825–26830. doi:10.1039/C9RA04636D. ISSN 2046-2069. PMC 9070433.

- ^ Jiang, Jie; Zhu, Liping; Wu, Yazhen; Zeng, Yujia; He, Haiping; Lin, Junming; Ye, Zhizhen (February 2012). "Effects of phosphorus doping in ZnO nanocrystals by metal organic chemical vapor deposition". Materials Letters. 68: 258–260. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2011.10.072.

- ^ Giallonardo, J.D.; Erb, U.; Aust, K.T.; Palumbo, G. (21 December 2011). "The influence of grain size and texture on the Young's modulus of nanocrystalline nickel and nickel–iron alloys". Philosophical Magazine. 91 (36): 4594–4605. doi:10.1080/14786435.2011.615350. S2CID 136571167.

- ^ a b Chandross, Michael; Argibay, Nicolas (March 2020). "Ultimate strength of metals". Physical Review Letters. 124 (12): 125501–125505. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.124.125501. PMID 32281861.

- ^ a b c d e Gleiter, Herbert (1989). "Nanocrystalline materials". Progress in Materials Science. 33 (4): 223–315. doi:10.1016/0079-6425(89)90001-7.

- ^ Cordero, Zachary; Knight, Braden; Schuh, Christopher (November 2016). "Six decades of the Hall–Petch effect – a survey of grain-size strengthening studies on pure metals". International Materials Reviews. 61 (8): 495–512. doi:10.1080/09506608.2016.1191808. hdl:1721.1/112642. S2CID 138754677.

- ^ Detor, Andrew; Schuh, Christopher (November 2007). "Microstructural evolution during the heat treatment of nanocrystalline alloys". Journal of Materials Research. 22 (11): 3233–3248. doi:10.1557/JMR.2007.0403.

- ^ Wollmershauser, James; Feigelson, Boris; Gorzkowski, Edward; Ellis, Chase; Gosami, Ramasis; Qadri, Syed; Tischler, Joseph; Kub, Fritz; Everett, Richard (May 2014). "An extended hardness limit in bulk nanoceramics". Acta Materialia. 69: 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2014.01.030.

- ^ Cha, Seung; Hong, Soon; Kim, Byung (June 2003). "Spark plasma sintering behavior of nanocrystalline WC–10Co cemented carbide powders". Materials Science and Engineering: A. 351 (1–2): 31–38. doi:10.1016/S0921-5093(02)00605-6.

- ^ Ward, Austin; French, Matthew; Leonard, Donovan; Cordero, Zachary (April 2018). "Grain growth during ultrasonic welding of nanocrystalline alloys". Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 254: 373–382. doi:10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2017.11.049.