Michael Sattler

Michael Sattler (1490 – 20 May 1527) was a monk who left the Roman Catholic Church during the Protestant Reformation to become one of the early leaders of the Anabaptist movement. He was particularly influential for his role in developing the Schleitheim Confession. His leadership has been seen as stabilizing and giving direction to the early Anabaptist movement after the first leaders had been scattered or martyred.[1]

He was convicted of heresy by Roman Catholic authorities and subsequently tortured and then burned to death at the stake.

| Part of a series on |

| Anabaptism |

|---|

|

|

|

Life

Sattler was born around 1490 in Staufen, Germany.[2] He became a Benedictine monk in the abbey of St. Peter, and probably became a prior.[2] He left St. Peter's probably in May 1525, when the monastery had been taken by troops from the Black Forest fighting in the German Peasants' War.[3] He later married a former Beguine named Margaretha.[4]

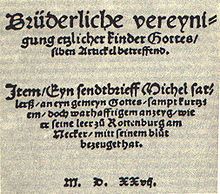

The date of Sattler's arrival in Zurich is not known, but he was expelled from that city on 18 November, 1525, in a wave of expulsions of foreigners resulting from the disputation on baptism of 6–8 November.[5] Some believe that Sattler was the "Brother Michael in the white coat" mentioned in a document dated 25 March of that year,[6] which would place him in Zurich before Snyder's estimation of when he left St. Peter's.[7] Snyder believed that Sattler may have arrived in Zurich to attend that disputation.[8] However, it may have been Michael Wüst who wore the white coat.[9] Sattler became associated with the Anabaptists and was probably rebaptised in the summer of 1526. He was involved in missionary activity around Horb and Rottenburg, and eventually traveled to Strasbourg. While in Strasbourg, he had extended discussions with the Protestant leaders of the city, Martin Bucer and Wolfgang Capito. Both of these men held Sattler in relative esteem for his character, even though they disagreed with him in certain points of doctrine and practice.[10] In February 1527 he chaired a meeting of the Swiss Brethren at Schleitheim, at which time the Schleitheim Confession was adopted.

In May 1527, Sattler was arrested by Austrian authorities, along with his wife and several other Anabaptists. He was kept a prisoner in the tower of Binsdorf in Baden-Württemberg.[11] The Catholic ruler of Austria, Archduke Ferdinand, urged that Sattler be immediately executed by drowning due to his prominence in the Anabaptist movement. However, Joachim I Nestor, Elector of Brandenburg had an interest in due process,[a] and wanted Sattler to undergo a trial procedure at Rottenburg am Neckar. Joachim assembled Catholic theologians and a group of twenty-four judges, which he chaired. Jakob Halbmayer, mayor of Rottenberg and himself an opponent of Sattler, was appointed to be Sattler's defense attorney.

Sattler was charged with defying the emperor, rejecting the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, rejecting infant baptism, rejecting extreme unction, dishonoring the saints, teaching against oaths, practicing the love feast, marrying, and advocating nonresistance. Sattler denied that he had defied the imperial edicts or dishonored the saints, but defended the remaining charges as moral and biblical. He also denied that courts should have jurisdiction in religious doctrine.[13]

Sattler was convicted. The sentence to execution read, "Michael Sattler shall be committed to the executioner. The latter shall take him to the square and there first cut out his tongue, and then forge him fast to a wagon and there with glowing iron tongs twice tear pieces from his body, then on the way to the site of execution five times more as above and then burn his body to powder as an arch-heretic."[14] The other men in the group were executed by sword, and the women, including Margaretha, were executed by drowning.

A memorial plaque at the site of his execution near Rottenburg am Neckar reads: "The Baptist Michael Sattler was executed by burning after severe torture on 20 May 1527 here on the "Gallows Hill". He died as a true witness of Jesus Christ. His wife Margaretha and other members of the congregation were drowned and burned. They acted for the baptism of those who want to follow Christ, for an independent congregation of the faithful, for the peaceful message of the Sermon on the Mount."

See also

- Martyrs Mirror, which includes an account of his death.

Notes

- ^ Joachim I introduced Roman law and established a new supreme court during his reign, called a Kammergericht.[12] For more on the legal situation in this era, see Reichskammergericht and Privilegium de non appellando.

Citations

- ^ Ste. Marie 2019, pp. 1–4.

- ^ a b Yoder 1973, p. 10.

- ^ Snyder 1984, p. 64.

- ^ Snyder 1984, p. 101.

- ^ Snyder 1984, p. 79.

- ^ Leonhard von Muralt and Walter Schmid eds. Quellen zur Geschichte der Täufer in der Schweiz I: Zürich (Zurich: S. Hirzel, 1952), p. 136.

- ^ E.g. Fritze Blanke, Brothers in Christ: The History of the Oldest Anabaptist Congregation, Zollikon, near Zurich, Switzerland (Scottsdale, Pennsylvania: Herald, 1961).

- ^ Fritze Blanke, Brothers in Christ: The History of the Oldest Anabaptist Congregation, Zollikon, near Zurich, Switzerland (Scottsdale, Pennsylvania: Herald, 1961), p. 82.

- ^ Ste. Marie 2019, pp. 37–39.

- ^ Ste. Marie 2019, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Deetjen, Werner-Ulrich (1985), 700 Jahre Stadt Ebingen - Geschichte in Bildern Vorträgezur Geschichte: Das Reich Gottes zu Ebingen-Gedanken zu seiner Geschichte und Eigenart [700 years of the City of Ebingen - History in Pictures Lectures on History: The Kingdom of God to Ebingen-thoughts about its history and peculiarity] (in German), Albstadt: Druck und Verlagshaus Daniel Balingen

- ^ Carlyle & Sanderson 1909, p. 21.

- ^ Estep 1996, p. 67-70.

- ^ Hutterite Large Chronicle, quoted in William Roscoe Estep, The Anabaptist Story, 3rd edition (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1960, p. 57.

References

- Carlyle, T.; Sanderson, E. (1909). The Life of Frederick the Great. A. C. McClurg & Company.

- Estep, W.R. (1996). The Anabaptist Story: An Introduction to Sixteenth-Century Anabaptism. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-0886-8.

- Gstohl, Mark (2004), "Michael Sattler", Theological Perspectives of the Reformation, Xavier University of Louisiana, retrieved 17 September 2017

- Horsch, John (1995) [1942]. Mennonites In Europe. Rod and Staff. pp. 70–78. Cited at http://www.anabaptists.org/history/sattler.html

- Kauffmann, Karl-Hermann (2010). Michael Sattler: ein Märtyrer der Täuferbewegung (in German). Brosamen-Verlag Albstadt. ISBN 978-3-00-032755-1.

- Snyder, C. Arnold (1984). The Life and Thought of Michael Sattler. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press. ISBN 0-8361-1264-4.

- Ste. Marie, Andrew V. (2019). I Appeal to Scripture!: The Life and Writings of Michael Sattler. Manchester, MI: Sermon on the Mount Publishing. ISBN 978-1-68001-027-5.

- Yoder, John Howard (1973). The Legacy of Michael Sattler. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press. ISBN 978-0-8361-1187-3.

External links

- Bossert, Gustav Jr.; Bender, Harold S.; Snyder, C. Arnold (1989). "Sattler, Michael (d. 1527)". In Roth, John D. (ed.). Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- Memorial stone at location of Michael Sattler's execution in Rottenburg, Germany, Sites of Memory webpage

- Theological Biography of Michael Sattler at Baptisttheology.org

- Two Kinds of Obedience Modern English version of tract usually attributed to Sattler

- [1] Website of Michael Sattler House associated with St. John's Abbey, Collegeville, MN

- [2] Powerpoint "Michael Sattler and the Peasants Revolt of 1525" for the 2013 Michael Sattler Conference