Law French

| Law French | |

|---|---|

| Lawe Frensch | |

| Region | Great Britain and Ireland |

| Era | Used in English law from c. 13th century until c. 18th century |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

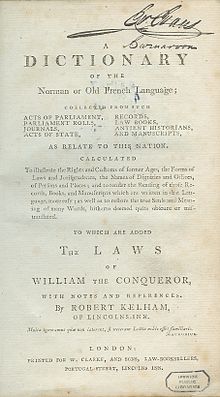

Law French (Middle English: Lawe Frensch) is an archaic language originally based on Anglo-Norman, but increasingly influenced by Parisian French and, later, English. It was used in the law courts of England from the 13th century.[3] Its use continued for several centuries in the courts of England and Wales and Ireland. Although Law French as a narrative legal language is obsolete, many individual Law French terms continue to be used by lawyers and judges in common law jurisdictions.

History

The earliest known documents in which 'French', i.e. Anglo-Norman, is used for discourse on English law date from the third quarter of the thirteenth century, and include two particular documents. The first is the 1258 The Provisions of Oxford,[4] consisting of the terms of oaths sworn by the 24 magnates appointed to rectify abuses in the administration of King Henry III, together with summaries of their rulings. The second is The Casus Placitorum[5] (c. 1250 – c. 1270), a collection of legal maxims, rules and brief narratives of cases.

In these works the language is already sophisticated and technical, well equipped with its own legal terminology. This includes many words which are of Latin origin, but whose forms have been shortened or distorted in a way which suggests that they already possessed a long history of French usage. Some examples include advowson from the Latin advocationem, meaning the legal right to nominate a parish priest; neif[e], from the Latin nātīvā, meaning a female serf, and essoyne or essone from the Latin sunnis, meaning a circumstance that provides exemption from a royal summons. Later essonia replaced sunnis in Latin, thus replacing into Latin from the French form.

Until the early fourteenth century, Law French largely coincided with the French used as an everyday language by the upper classes. As such, it reflected some of the changes undergone by the northern dialects of mainland French during the period. Thus, in the documents mentioned above, 'of the king' is rendered as del rey, or del roy, whereas by about 1330 it had become du roi, as in modern French, or du roy.[6][7]

During the 14th century, vernacular French suffered a rapid decline. The use of Law French was criticized by those who argued that lawyers sought to restrict entry into the legal profession. The Pleading in English Act 1362 ("Statute of Pleading") acknowledged this change by ordaining that thenceforward all court pleading must be in English, so "every Man ... may the better govern himself without offending of the Law".[8] From that time, Law French lost most of its status as a spoken language.

Law French remained in use for the 'readings' (lectures) and 'moots' (academic debates), held in the Inns of Court as part of the education of young lawyers, but essentially it quickly became a written language alone. It ceased to acquire new words. Its grammar degenerated. By about 1500, gender was often neglected, giving rise to such absurdities as une home ('a (feminine) man') or un feme ('a (masculine) woman'). Its vocabulary became increasingly English, as it was used solely by English, Welsh and Irish lawyers and judges who often spoke no real French.

In the seventeenth century, the moots and readings fell into neglect, and the rule of Oliver Cromwell, with its emphasis on removing the relics of archaic ritual from legal and governmental processes, struck a further blow at the language. Even before then, in 1628, Sir Edward Coke acknowledged in his preface to the First Part of the Institutes of the Law of England, that Law French had almost ceased to be a spoken tongue. It was still used for case reports and legal textbooks until almost the end of 1600s, but only in an anglicized form. A frequently quoted example of this change comes from one of Chief Justice Sir George Treby's marginal notes in an annotated edition of Dyer's Reports, published 1688:

Richardson Chief Justice de Common Banc al assises de Salisbury in Summer 1631 fuit assault per prisoner la condemne pur felony, que puis son condemnation ject un brickbat a le dit justice, que narrowly mist, et pur ceo immediately fuit indictment drawn per Noy envers le prisoner et son dexter manus ampute et fix al gibbet, sur que luy mesme immediatement hange in presence de Court.

"Richardson, Chief Justice of the Common Bench at the Assizes at Salisbury in Summer 1631 was assaulted by a prisoner there condemned for felony, who, following his condemnation, threw a brickbat at the said justice that narrowly missed, and for this, an indictment was immediately drawn by Noy against the prisoner and his right hand was cut off and fastened to the gibbet, on which he himself was immediately hanged in the presence of the Court."[9][note 1]

The Proceedings in Courts of Justice Act 1730 made English, instead of Law French and Latin, the obligatory language for use in the courts of England and in the court of exchequer in Scotland. It was later extended to Wales, and seven years later a similar act was passed in Ireland, the Administration of Justice (Language) Act (Ireland) 1737.[10]

Survivals in modern legal terminology

The postpositive adjectives in many legal noun phrases in English—attorney general, fee simple—are a heritage from Law French. Native speakers of French may not understand certain Law French terms not used in modern French or replaced by other terms. For example, the current French word for "mortgage" is hypothèque. Many of the terms of Law French were converted into modern English in the 20th century to make the law more understandable in common-law jurisdictions. Some key Law French terms remain, including the following:

| Term or phrase | Literal translation | Definition and use |

|---|---|---|

| assizes | sittings (Old French assise, sitting) | Sitting of the court held in different places throughout a province or region.[11] |

| attorney | appointed (Old French atorné) | attorney-at-law (lawyer, equivalent to a solicitor and barrister) or attorney-in-fact (one who has power of attorney). |

| autrefois acquit or autrefois convict | peremptory pleas that one was previously acquitted or convicted of the same offence. | |

| bailiff | Anglo-Norman baillis, baillif "steward; administrator", from bail "custody, charge, office" |

|

| charterparty | Originally charte partie (split paper) | Contract between an owner and a hirer (charterer) over a ship. |

| cestui que trust, cestui que use | shortened form of cestui a que use le feoffment fuit fait, "he for whose use the feoffment was made", and cestui a que use le trust est créé, "he for whom the trust is created" | sometimes shortened to cestui; the beneficiary of a trust. |

| chattel | property, goods (Old French chatel, ultimately from Latin capitale) | personal property |

| chose | thing (from Latin causa, "cause") | thing, usually as in phrases: "chose in action" and "chose in possession". |

| culprit | Originally cul. prit, abbreviation of Culpable: prest (d'averrer nostre bille), meaning "guilty, ready (to prove our case)", words used by prosecutor in opening a trial. | guilty party |

| cy-près doctrine | "so near/close" and can be translated as "as near as possible" or "as near as may be" | the power of a court to transfer the property of one charitable trust to another charitable trust when the first trust may no longer exist or be able to operate. |

| defendant | "defending" (French défendant) | the party against whom a criminal proceeding is brought. |

| demise | "to send away", from démettre | Transfer, usually of real property, but also of the Crown on the monarch's death or abdication, whence the modern colloquial meaning "end, downfall, death". |

| de son tort | "by his wrong", i.e. as a result of his own wrong act | acting and liable but without authorization; e.g. executor de son tort, trustee de son tort, agent de son tort, guardian de son tort. |

| en ventre sa mère | "in its mother's womb" | foetus in utero or in vitro but for beneficial purposes legally born. |

| escheats | Anglo-Norman eschete, escheoite "reversion of property" (gave the legal French verb échoir) |

|

| escrow | Anglo-Norman escrowe, from Old French escro(u)e "scrap of paper, scroll of parchment" | a contractual arrangement in which a third party receives and disburses money or property for the primary transacting parties, with the disbursement dependent on conditions agreed to by the transacting parties |

| estoppel | Anglo-Norman estoup(p)ail "plug, stopper, bung" | prevention of a party from contradicting a position previously taken. |

| estovers | "that which is necessary" | wood that tenants may be entitled to from the land in which they have their interest. |

| feme covert vs. feme sole | "covered woman" vs. "single woman" | the legal status of adult married women and unmarried women, respectively, under the coverture principle of common law. |

| force majeure | modern French, "superior force" | clause in some contracts that frees parties from liability for acts of God. |

| grand jury | "large jury" (q.v.) | a legal body empowered to conduct official proceedings and investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. |

| in pais | "in the countryside" | out of court, extrajudicial: (1) settlement in pais: voluntary amicable settlement reached without legal proceedings; (2) matter in pais: matter to be proved solely by witness testimony unsupported by any judicial record or other documentary or tangible evidence; (3) estoppel in pais: estoppel in respect of out-of-court statements; (4) trial per pais: trial by jury. |

| jury | Anglo-Norman jurée "oath, legal inquiry" | a group of citizens sworn for a common purpose. |

| laches | Anglo-Norman lachesse "slackness, laxness" | Under English common law, the unnecessary delaying bringing an action against a party for failure to perform is known as the doctrine of laches. The doctrine holds that a court may refuse to hear a case not brought before it after a lengthy period since the right of action arose.[11] |

| larceny | Anglo-Norman lar(e)cin "theft" | theft of personal property. |

| mainprise, mainprize | undertaking for the appearance of an accused at trial, given to a magistrate or court even without having the accused in custody; mainpernor is the promisor. | |

| marché ouvert | "open market" | a designated market in which sales of stolen goods to bona fide purchasers are deemed to pass good title to the goods. |

| mortgage | "dead pledge" (Old French mort gaige) | now a variety of security interests, either made by conveyance or hypothecation, but originally a pledge by which the landowner remained in possession of the property he staked as security. |

| mortmain | mort + main meaning "dead hand" | perpetual, inalienable ownership of land by the "dead hand" of an organization, usually the church. |

| oyer et terminer | "to hear and determine" | US: court of general criminal jurisdiction in some states; UK: commission or writ empowering a judge to hear and rule on a criminal case at the assizes. |

| parol evidence rule | a substantive rule of contract law which precludes extrinsic evidence from altering the terms of an unambiguous fully expressed contract; from the Old French for "voice" or "spoken word", i.e., oral, evidence. | |

| parole | word, speech (ultimately from Latin parabola, parable) | the release of prisoners based on giving their word of honour to abide by certain restrictions. |

| peine forte et dure | strong and harsh punishment | torture, in particular to force a defendant to enter a plea. |

| per my et per tout | by half and by the whole | describes a joint tenancy: by the half for purposes of survivorship, by the whole for purposes of alienation. |

| petit jury | "small jury" | a trial jury, now usually just referred to as a jury. |

| plaintiff | complaining (from Old French plaintif) | the person who begins a lawsuit. |

| prochein ami | close friend | Law French for what is now more usually called next friend (or, in England and Wales, following the Woolf Reforms, a litigation friend). Refers to one who files a lawsuit on behalf of another not capable of acting on his or her own behalf, such as a minor. |

| profit a prendre | also known as the right of common, where one has the right to take the "fruits" of the property of another, such as mining rights, growing rights, etc. | |

| prout de jure | Scots law term; proof at large; all evidence is allowed in court. | |

| pur autre vie vs. cestui que vie | "during the term of another person's life" vs. "during the term of one's life" |

|

| recovery | originally a procedural device for clarifying the ownership of land, involving a stylised lawsuit between fictional litigants. | |

| remainder | originally a substitution-term in a will or conveyance, to be brought into play if the primary beneficiary were to die or fail to fulfil certain conditions. | |

| replevin | from plevir ("to pledge"), which in turn is from the Latin replegio ("redeem a thing taken by another"). | a suit to recover personal property unlawfully taken. |

| semble | "it seems" or "it seems or appears to be" | The legal expression "semble" indicates that the point to which it refers is uncertain or represents only the judge's opinion. In a law report, the expression precedes a proposition of law which is an obiter dictum by the judge, or a suggestion by the reporter. |

| terre-tenant | person who has the actual possession of land; used specifically for (1) someone owing a rentcharge, (2) owner in fee of land acquired from a judgment debtor after judgment creditor's lien has attached. | |

| torts | from medieval Latin tortum "wrong, injustice", neuter past participle of Latin torquo, "I twist" | civil wrongs. |

| treasure trove | from tresor trouvé "found treasure" | treasure found by chance, as opposed to one stolen, inherited, bought, etc. Trove is properly an adjective, but colloquially now used as a noun, meaning a collection of treasure, whether it is legally treasure trove or not. In the UK (except Scotland), the legal term is now simply treasure. |

| voir dire | literally "to say the truth";[14][15] the word voir (or voire) in this combination comes from Old French and derives from Latin verum, "that which is true". It is not related to the modern French word voir, which derives from Latin video ("I see"); but instead to the adverb voire ("even", from Latin vera, "true things") as well as the adjective vrai ("true") as in the fossilised expression à vrai dire ("to say the truth"). | in the United States, the questions a prospective juror or witness must answer to determine his qualification to serve; or, in the law of both the United States and of England a "trial-within-a-trial" held to determine the admissibility of evidence (for example, an accused's alleged confession),[16] i.e. whether the jury (or judge where there is no jury) may receive it. |

See also

- French language

- Norman language

- French phrases used by English speakers

- English words of French origin

- Influence of French on English

- Jersey Legal French

- Franglais

- List of legal Latin terms

- Legal English

Notes

- ^ The macaronic nature of this production can be more easily seen if it is reproduced in a modernized form with the (pseudo) French elements in bold, (pseudo) Latin in italics and bold, and the rest in English: "Richardson, Chief Justice de Common Banc aux assizes de Salisbury in Summer 1631 fuit assaulted per prisoner là condemné pour felony, que puis son condemnation jeta un brickbat au dit justice, que narrowly missed, et pour cela immediately fuit indictment drawn per Noy envers le prisoner et son dexter manus amputée et fixée au gibbet, sur que lui-même immédiatement hangé in presence de Court." Admittedly, many of the English words (assault, prisoner, condemn, gibbet, presence, Court) could be interpreted as misspellings (or alternative spellings) of French words, while justice is the same in French as in English; but even under the most favourable analysis, the note represents poor usage of French, English, and Latin simultaneously. What is perhaps most striking is that Treby could not remember the French even for a concept as familiar at the time as being 'hanged' (pendu). Perhaps even more striking is the use of both the French and English words for "immediately" and the use of Old French ("ceo") and Latin ("fuit") forms of non-legal and, in fact, core vocabulary.

References

- ^ a b Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (24 May 2022). "Glottolog 4.8 - Oil". Glottolog. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ Manuel pratique de philologie romane, Pierre Bec, 1970–1971

- ^ Laske, Caroline (1 April 2016). "Losing touch with the common tongues – the story of law French". International Journal of Legal Discourse. 1 (1): 169–192. doi:10.1515/ijld-2016-0002. hdl:1854/LU-7239351. ISSN 2364-883X.

- ^ Printed in William Stubbs, Select Charters illustrative of English Constitutional History (9th ed., ed. H. C. F. Davis) (Oxford, 1913), pp. 378 et seqq.

- ^ W. F. Dunham (ed.), The Casus Placitorum and Cases in the King's Courts 1272–1278 (Selden Society, vol. 69) (London, 1952)

- ^ "Cotton MS Vitellius A XIII/1". Les roys de Engeltere. 1280–1300. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

Five rectangles of red linen, formerly used as curtains for the miniatures.ff. 3–6: Eight miniatures of the kings of England from Edward the Confessor (r. 1042–1066) to Edward I (r. 1272–1307); each one except the last is accompanied by a short account of their reign in Anglo-Norman prose. 'del Roy Phylippe de Fraunce'

- ^ Many examples in D. W. Sutherland (ed.), The Eyre of Northamptonshire, 3–4 Edward III, A.D. 1329–1330 (Selden Society, vol. 97–8) (London, 1983) (note however that this text also shows instances of rei or rey)

- ^ Peter M. Tiersma, A History Of The Languages Of Law (2012), accessed 2 February 2018

- ^ Legal Language, Peter Tiersma, p. 33

- ^ "Northern Ireland Act 1998 (Amendment No. 1)" (PDF). www.assets.publishing.service.gov.uk. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d Willes, John A; Willes, John H (2012). Contemporary Canadian Business Law: Principles and Cases (9th ed.). McGraw-Hill Ryerson.

- ^ a b Yogis, John (1995). Canadian Law Dictionary (4th ed.). Barron's Education Series.

- ^ Benson, Marjorie L; Bowden, Marie-Ann; Newman, Dwight (2008). Understanding Property: A Guide (2nd ed.). Thomson Carswell.

- ^ "Voir dire". Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School.

- ^ voir dire. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ See, generally, Archbold's Criminal Pleading 2012 (London, Sweet & Maxwell) at 4-357

Literature

- Manual of Law French by J. H. Baker, 1979.

- The Mastery of the French Language in England by B. Clover, 1888.

- "The salient features of the language of the earlier year books" in Year Books 10 Edward II, pp. xxx–xlii. M. D. Legge, 1934.

- "Of the Anglo-French Language in the Early Year Books" in Year Books 1 & 2 Edward II, pp. xxxiii–lxxxi. F. W. Maitland, 1903.

- The Anglo-Norman Dialect by L. E. Menger, 1904.

- From Latin to Modern French, with especial Consideration of Anglo-Norman by M. K. Pope, 1956.

- L'Evolution du Verbe en Anglo-Français, XIIe-XIVe Siècles by F. J. Tanquerey, 1915.