LGBTQ history in Poland

Although homosexuality has been legal in Poland since 1932, the country's LGBTQ rights are among the most restricted in Europe.[1] Homosexuality has been a taboo subject for most of Poland's history; combined with a lack of legal discrimination, this has often led to a lack of historical sources on the subject. Homophobia has been a common public attitude in Poland because of the influence of Catholic Church in Polish public life and widespread social conservatism.[2] Homosexuality in Poland was decriminalized in 1932, but recriminalized by the German authorities following the invasion of Poland in 1939.[3][4]

Early history

Due to a lack of historical sources and censorship by the Catholic Church over the centuries, it is difficult to reconstruct Slavic religions, customs and traditions when it comes to LGBT people.[5]

Many, if not all, Slavic countries that accepted Christianity, adopted a custom of making church-recognized vows between two people of the same sex (normally men) called bratotvorenie/pobratymienie/pobratimstvo—translation of the Greek adelphopoiesis—the "brother making" ceremony. The precise nature of this relationship is still highly controversial; some historians interpret them as essentially a homosexual marriage of men. Such ceremonies can be found in the history of the Catholic Church until the 14th century,[6] and in the Eastern Orthodox Church until the early 20th century.[7][8][9] Indeed, in Polish sources the vows for bratotvorenije appear in Orthodox prayer books as late as the 18th century [10] in the Chełm and Przemyśl regions.[10]

Bolesław V the Chaste never consummated his marriage, which some historians see as a sign of his homosexuality.[11]

Throughout history, homosexuality, be it true or alleged, was often weaponised for use by individuals against their ideological or political enemies, and to defame dead historical figures. Bolesław the Bold was accused of "sodomy" by the medieval historian Jan Długosz.[2] He also attributed the defeat and death of Władysław III, the only crusader king not canonized at the Varna, to the king laying with a man before this decisive battle.[2]

Magdeburg Law, under which many towns were built,[note 1] punished breaking the 6th Commandment ("Thou shalt not commit adultery") by death; however, the actual punishments for adultery given out by the judges in recorded cases included prison, financial fines or being pilloried.[12] Soon the general public's opinion of extramarital sex became more lenient.[2][13] The only known death sentence carried out for "sins against nature" was the case of Wojciech Skwarski from Poznań in 1561. Wojciech was considered male, until doubts in his youth arose and his gender was inspected by officials and mayor of Poznań. They decided Wojciech was female and should be dressed as a woman and known as such by the local community from now on. After running away from Poznań, Wojciech travelled around the country and married, as a woman, three men—Sebastian Słodownik from Poznań, Wawrzyniec Włoszek from Kraków and Jan the blacksmith (married during Wojciech's marriage with Wawrzyniec). The sentence (burning at the stake) took into account Wojciech's other misdeeds such as frequent thefts, hitting (and probably killing) their first husband with a brick during an argument, sleeping with many women (including married women) and having a public house in Poznań.[14][15] The case of Wojciech and their ambiguous sex and gender was described (with case file from 1561 republished) by physician Leon Wachholz in his work on "history of hermaphroditism", which suggest they might have been intersex.[16] The only other sentence for the act of sodomy (public beating and exile) was the case of Agnieszka Kuśnierczanka, in 1642, who dressed as a man and committed "imaginary male courtship".[17] Other judicial documents mention same-sex relationships without using derogatory terminology. They are mentioned in a neutral manner as facts in cases of unrelated crimes, showing that same-sex relationships were silently tolerated and not actively prosecuted.[18]

During the Baroque period the general public ignored homosexuality. It was considered it an exception that came from the "degenerate" West and happened among the nobility who had contacts there and the mentally ill.[19] Turkey was considered one of the places where lesbian relationships originated.[20] 18th century travelers shared those beliefs and praised Poland, contrasting it with its neighbours.[21] Accusations of sodomy were still used as a method to diminish political opponents, as was the case of Władysław IV, Michał Korybut Wiśniowiecki and Jakub Sobieski.[22]

According to the chronicler Marcin Matuszewicz, Prince Janusz Aleksander Sanguszko of Dubno, "kept men for amorous purposes". (His wife, Konstancja Denhoff, returned to her parents "without receiving any marital proof from her husband except for one good morning at dawn and one good night in the evening"). He donated the town of Koźmin and seventeen villages to his lover, Karol Szydłowski.[22] Sanguszko had a string of openly endorsed (and financed by him) favourites until Kazimierz Chyliński, whose father who wanted him to return to his wife, was arrested in Gdańsk and jailed for 12 years.[23] After this incident Sanguszko kept only secret lovers until his father's death, but then returned to past practices. It is worth noting that Sanguszko was unafraid of publicly keeping male lovers while maintaining the public position of a Lithuanian Miecznik (sword-bearer).[22] Similarly, Jerzy Marcin Lubomirski had a young Cossack boy favourite, whom he made rich and noble (buying the status from Poniatowski).[24] The prince, who had four short marriages and numerous female and male lovers, was the subject of a newspaper-reported scandal, when he appeared in women's clothing at a Warsaw masked ball in 1782.[2]

During the Enlightenment period, despite the fascination with antiquity and the intellectual liberalisation, homophobic beliefs did not completely disappear: the medical profession considered "sexual deviations" (homosexuality, incest, zoophilia, etc.) a sign of "mental degeneration".[25]

Partitions

The Napoleonic Code, introduced in the Duchy of Warsaw in 1808, was silent on homosexuality.[2] After 1815, all three countries that partitioned Poland explicitly declared homosexual acts illegal.[26] In Congress Poland homosexuality was criminalised in 1818, in Prussia in 1871 and in Austria in 1852.[26] Russia's new code of law (called Kodeks Kar Głównych i Poprawczych/Уложение о наказаниях уголовных и исправительных 1845 года) in 1845 penalized homosexuality with forced resettlement to Siberia.[27]

In 19th century, due to men being often absent (insurrections, exiles to Siberia etc.), Polish women would often take on traditionally masculine tasks, such as household management.[28] The social norms were more lax on the countryside, allowing women there to have more liberties than in the cities or in the Western Europe.[28] There are known examples of women living together with their long-time female partners, such as the writer Maria Konopnicka and painter Maria Dulębianka, Maria Rodziewiczówna and Helena Weychert or Paulina Kuczalska-Reinschmit and Józefa Bojanowska.[28] Women's rights activist Romana Pachucka (1886-1964) would later mention in her diaries those pairs, noticing that in every couple one of the women would present herself more masculine, and the other more feminine.[29] It is known that Narcyza Żmichowska had an affair with a daughter of a rich magnate, which later inspired her to write a novel titled Poganka ("Pagan Woman").[2] In 1907, another writer, previously known as Maria Komornicka, burned female dresses, announced his new, male name—Piotr Odmieniec Włast— and continued to dress like a man and write under that name.[30]

Second Polish Republic

The magazine Wiadomości Literackie ("Literature News") which published many writers of the period, frequently covered issues that broke Polish sexual and moral taboos, such as contraception, menstruation or homosexuality. The most well known advocates of such topics were Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński and Irena Krzywicka.[31] They were considered propagators of "moral reform (IE deform)" by Czesław Lechicki and others. In 1935 Boy-Żeleński, Wincenty Rzymowski and Krzywicka, among others, established the Liga Reformy Obyczajów (League of Reform of (Moral) Customs).[26]

The taboo-breaking discussions were limited only to literary circles and were ignited by women's emancipation movements, while mainstream (Catholic) society was still prejudiced and viewed homosexuality as a sin. The writers were eager to include gay subplots in their works and to analyze the psyche of homosexual and bisexual characters.[26] Many cultural figures were also out as gay or bisexual in their communities including Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz and Maria Dąbrowska.[26] Examples of gay subplots include the writings of Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, Zofia Nałkowska (Romans Teresy Hennert), Jan Parandowski (Król Życia, Adam Grywałd) and the opera King Roger by gay composer Karol Szymanowski which stirred up a controversy at its premiere.[32] The only draft of his gay novel Ephebos was burned in the apartment of the novel's keeper, Iwaszkiewicz, in September 1939.[28] Lesbian writings also existed, with 1933 seeing publications of three novels with openly lesbian themes: Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness with a preface by Irena Krzywicka, Maria Modrakowska’s Anetka, and Aniela Gruszecka's Przygoda w nieznanym kraju [An Adventure in an Unknown Country]. A testimony of an anonymous Polish-Jewish woman, imprisoned in concentration camp at age 12, who survived because she "wanted to live long enough to kiss a woman" having had read The Well of Loneliness implies that those texts reached and affected the lesbian population.[33]

In late 1920s Warsaw "pederasty" (pederastja) was tracked by 6th Sanitary-Moral Brigade of the city's police, who organized a hunt on local cruising spots in 1927. In 1925 female 1st Brigade joined the task, and was responsible for arresting the cruisers in 1927. A lot of the arrested were working class males who identified as "ciota" (aunty), wearing makeup and using female nicknames and grammar forms.[34]

Homosexual life existed also in the countryside, as the 1925 Suwalki court case of Stefan Góralski and Marjan Kuleszyński shows. The two men met in 1922 going to Kresy, and then moved to Suwałki, having made a secret oath, now interpreted as a "same-sex secret marriage ritual". When the relationship fell apart, Góralski reported Kuleszyński to authorities. During the court case, questioned villagers talked about a lack of “abnormality” or “sexual perversion” in the defendants, indicated they accepted them in the community. In May 1925, Kuleszyński and Góralski were convicted for 3 months of prison under paragraph 516 of the Russian Penal Code of 1903.[35]

In 1932, the laws of independent Poland decriminalised homosexuality, which was legal then, but still a taboo. One of the reasons was protecting higher-class gay men from blackmail,[34] the other was a eugenicist belief of Polish psychiatrists that homosexuality was genetically inherited, and so persecuted gay men would marry women and reproduce their "defect".[35] This It also resulted in there being less historical material (such as police reports or court transcripts) about the gay subculture of the inter-war period than in many other European countries.[26]

Several stories of LGBTI people made it to the press as "sensations", such as a murder of a lawyer Konrad Meklenburg in September 1923, with several newspapers in the country alluding to his "sexual anomaly" and "being seen with young boys" being motifs of the crime, and one newspaper claiming he was sentenced to prison for homosexuality in Germany.[36] Soon, in November 1923 a Warsaw tabloid "Express Poranny", followed by subsequent Warsaw and non-Warsaw newspapers, published sensational informations. accusing an openly feminist and lesbian doctor Zofia Sadowska of seducing female patients (including minors), organizing lesbian orgies with sadistic elements, running a lesbian brothel and administering drugs to women to make them dependent on her (the police investigation did not prove the truthfulness of the charges). These publications began a several-year-long "Ancient Greek (ie lesbian) scandal" related to the person of Dr. Sadowska, and several trials for libel, widely reported in the press and mocked in the cabarets, with several famous people involved. During the trial, questioned by the defense lawyer, Sadowska said that "the accusation of practicing lesbian love is not disgraceful". After the scandal, the figure of Zofia Sadowska as a scientist and doctor has been erased from collective memory.[37] In 1924 the tabloids reported on male-only “ball of fake breasts” in a private apartment in the city center.[35]

Another public figure that came to the press spotlight was a record-breaking athlete Zofia Smętek, whose masculine appearance was a source of many press rumours and cabaret jokes. Smętek, confirmed intersex by doctors in 1937, decided to undergo gender transition to male and sex reassignment surgery, and his press statement caused a further spike in the public interest, even international, with Witold Smętek (post-transition name) giving interview in 1939 to Reuters and becoming a topic of a French book Confession amoureuse d'une femme qui devint homme (Love Confession of a Woman who Became a Man).[38]

World War II

For a long time, it was believed that during the Nazi occupation of Poland in World War II gay and bisexual Poles were not a specifically persecuted category, that unlike gay and bisexual Germans were not punished by Article 175 and that they were only persecuted and killed as Poles.[26] Nowadays it is known that this was a mistaken assumption, and research into persecution of gay, bisexual and transfeminine[39] Poles is made.[40] The most well known Pole persecuted under Article 175 is Teofil Kosiński. Contrary to popular belief, Polish men in relationships with Polish men were also punished, primarily in areas incorporated into Germany.[40] In the General Government, Polish homosexual relations were investigated by the criminal police, who could deport them from Poland or treat them arbitrarily, e.g. with the death penalty.[40] In the camps, Poles sentenced under Paragraph 175 were treated as "political prisoners" and received red triangles.[40] Diaries, such as Z Auszwicu do Belsen by Marian Pankowski, Anus mundi by Wiesław Kielar are testimony to the experiences of gay prisoners during the war.[26]

During World War 2, a later Righteous Among the Nations Stanisław Chmielewski promised to his Jewish partner Władysław Bergman to protect his mother before parting ways. This led him to organize an informal conspiratory network that spun various classes and political affiliations and provided shelters and Kennkarte for several Jews, such as Janina Bauman. According to Gunnar S. Paulsson, the majority of the network consisted of gay men who knew each other before the war.[41]

Polish People's Republic

In 1948, the law set the age of consent for all sexual acts at 15 years of age.[2] Apart from that, the Interwar liberal laws on homosexuality have not changed.[26] The ruling communist party actively censored information about the Kinsey Report, so that the public would not know about its research and its discoveries.[26] The militia (police force) investigated gay subculture (due to it being very hermetic and closed) and tried to determine whether sexual orientation was a factor in criminal activity.[42] The militia's interest did not include lesbian and bisexual women who were "invisible" in public life.[26] According to Lukasz Sculz of the University of Antwerp, gay men in 1980's Poland were often at risk of physical violence from heterosexual men.[43]

As for transgender history, first sex reassignment surgery in Poland was carried out in 1963 in Szpital Kolejowy (Railway Hospital) in Międzylesie (modern day part of Wawer), but SRSs became carried out frequently around 20 years later.[44] First recorded meeting on transgender issues including transgender speakers and listeners took place 10 December 1985 in Department of Sexology and Pathology of Interpersonal Relations, Medical Center of Postgraduate Education in Warsaw. The records of this discussion were published in the book Apokalipsa Płci (Gender Apocalypse) by Kazimierz Imieliński and Stanisław Dulko.[45]

The Catholic Church, now a social force of resistance against the new system and still an important influence on Polish life, became a factor in making homosexuality something scandalous in many social circles and groups. However, Jerzy Zawieyski, who represented Catholics in parliament, was gay and lived with his partner Stanisław Trębaczkiewicz.[46] A gay subculture grew, mostly in areas where there was cruising for sex.[26] In the 70s, gay movements grew in Western Europe and some countries of the Soviet Block—East Germany (DDR) and the Soviet Union USSR—while Polish gay subculture tended to be less activist and more politically passive. This is attributed to the impact of Catholicism on Polish society and to lack of legal penalties for homosexual acts.[26]

The roots of Polish gay movements lie in letters sent to Western organizations, such as HOSI Wien (Austria's LGBT Association), and in reactions to the AIDS crisis.[26] In 1982 HOSI Wien created a sub-unit dedicated to Eastern Europe - EEIP (Eastern Europe Information Pool) [47] and proceeded to carry out pioneering work contacting and assisting the small, newly hatched LGBT groups in Eastern Europe. It also helped to bring them to the attention of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA), dominated by Western LGBT organizations unaware of the situation in Eastern Europe then.[26] Andrzej Selerowicz, who cooperated with EEIP, held conspiratorial meetings of Polish LGBT people in 1983 and 1984, and despite the general shame and anxiety about speaking out about LGBT topics by many of the guests, the meetings kick-started initiatives such as new groups and a samizdat style news bulletin Etap magazine.[48] A 1985 article "Jesteśmy inni" ("We are different") in the prominent weekly Polityka set off a national discussion on homosexuality.[49] In the same year the Ministry of Health established offices of Plenipotentiary for AIDS and a ten-person team of AIDS experts. This was a year before the first case of AIDS was noted in Poland.[26]

The Normal Heart, an autobiographical play by Larry Kramer, received its Polish premiere in 1987 at the Polish Theatre in Poznań where it was directed by Grzegorz Mrówczyński.[50] The Polish cast included Mariusz Puchalski as Ned Weeks and Mariusz Sabiniewicz as Tommy Boatwright, with Andrzej Szczytko as Bruce Niles and Irena Grzonka as Dr. Emma Brookner.[51] The television adaptation débuted on the TVP channel on 4 May 1989, one month before the first free election in the country since 1928.[52][53]

Operation Hyacinth

The government used traditional negative attitudes towards homosexuality as a means to harass, blackmail and recruit collaborators for the intelligence services.[54] The culmination of these practices was Operation Hyacinth launched on 15 November 1985, on the order of the Minister of Internal Affairs Czesław Kiszczak. On that morning, in different colleges, factories and offices across Poland, functionaries of the Służba Bezpieczeństwa (SB) (a secret police force) arrested numerous men suspected of being gay or of having connections with "homosexual groups".[26] Its purpose was to create a national database of all Polish gay men and people who were in touch with them,[54] and it resulted in the registration of around 11,000 people. Officially, Polish propaganda stated that the reasons for the action were as follows:[55]

- fear of the newly discovered HIV virus, as homosexuals were regarded as a group at high risk,

- control of homosexual criminal gangs (as gay subculture has been very hermetic)

- fighting prostitution.

There are suspicions that the operation was a not only means to blackmail and recruit collaborators, but that it was also aimed at developing human rights movements. Gay activist Waldemar Zboralski said in his memoirs the reason gay organizations were targeted was their active correspondence with Western organizations.[56] In 2005 it was revealed that "pink files" of victims of the operations are still held by the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN). Despite letters from LGBT activists asking that they be destroyed, IPN claimed it would be illegal for them to do so.[26]

Warsaw Gay Movement

In the counter-reaction to Operation Hyacinth, The Warsaw Gay Movement was started in a private meeting in 1987, initially only for gay men. The founders were a group of activists, led by Waldemar Zboralski, Sławomir Starosta and Krzysztof Garwatowski.[57] However, lesbians began joining the group during its first month of activity.[58][59]

The first activities of WRH focused on safe sex, anti-AIDS prevention and encouraging gay people to obtain HIV-tests. The reaction of the Polish mainstream media and Ministry of Health to the existence of the Warsaw Gay Movement was positive, unlike the reaction of general Czesław Kiszczak, minister of Home Affairs, who intervened in attempts of legalizing WRH as an organization under Associations Act in March 1988 – it was influenced by the Catholic Church[60]

The Warsaw Gay Movement was mentioned under the name "Warsaw Homosexual Movement" as a politically active group of the Polish independence movement, by Radio Free Europe analyst Jiří Pehe, in his survey published in 1988 and 1989.[61][62]

Third Polish Republic

On 28 October 1989 an association of groups known as Lambda was established, and registered by the Voivodeship Court in Warsaw on 23 February 1990. Among its priorities was spreading tolerance, raising awareness and preventing HIV.[63] With AIDS spreading, in spring 1990, Jarosław Ender and Sławomir Starosta started a campaign called Kochaj, nie zabijaj (Love, don't kill), a "social youth movement aiming for raising awareness about AIDS".[26]

The first issue of Inaczej (Differently), a magazine for sexual minorities or "those loving differently", (which became a common euphemism in Polish), was published in June 1990. The originator was Andrzej Bulski, under the nom de plume Andrzej Bul. He was the owner of Softpress publishing company, which had published several LGBT-oriented and related books in the 1990s.[26] 7 October 1990 was opening day for the club Café Fiolka at Puławska 257 in Warsaw—the first official gay club in Poland. It was closed in 1992 after repeated acts of vandalism.[63] 1991 saw the first Polish gay male monthly Okay (that closed in 1992), distributed nationwide in Ruch newsagent's shops. It was initially redacted by the writer and poet Tadeusz Olszewski, under the pen name of Tomasz Seledyn.[64]

The first official coming out in the Polish media was an article in September 1992 edition of Kobieta i Życie (Woman and Life) magazine about a renowned and well-known actor Marek Barbasiewicz.[65] The first public lesbian coming out was a declaration by Izabela Filipiak in the magazine Viva in 1998.[66]

Despite the birth of LGBT activism, some politicians chose to use fearmongering against LGBT citizens as a strategy to gain popularity. This included Kazimierz Kapera, the vice-minister of health, who was recalled from this position in a phone call from Prime Minister Jan Krzysztof Bielecki in May 1991 after saying on public television that homosexuality is a deviation and a reason for the AIDS epidemic.[26] On 14 February 1993, a group of people associated with Lambda held a demonstration under Sigismund's Column, calling for their "rights to love". It was the first LGBT public manifestation in Poland. In 1998 there was a happening where several LGBT people, including activist Szymon Niemiec, held cards with the names of their occupations while wearing face masks.[63] In the Spring of 1995 Polish immigrants established a group called Razem (Together) in New York, which served Polish LGBT immigrants in contacting the LGBT community in Poland and integrating themselves in America. Razem was a part of the Lesbian & Gay Community Services Center (L&GCSC).[26] In 1996, inspired by Olga Stefania, the OLA-Archiwum (Polish Feminist Lesbian Archive) was established and registered as an association in 1998. Between 1997 and 2000 OLA published eight issues of Furia Pierwsza (Fury the First), a "literary feminist lesbian magazine".[26] The first gay community internet portal Inna Strona (a Different Site) was created in September 1996. It was renamed Queer.pl and is still active. That same year the Polish Lesbians' Site was created.[26] In 1998, the Tęczowe Laury award (Rainbow Laurels), was given out for the first time for promoting tolerance and respect towards LGBT people. Jarosław Ender and Sławomir Starosta were the originators of the idea. Some of the people awarded the prize included: Kora, Zofia Kuratowska, Monika Olejnik, Jerzy Jaskiernia, and the daily Gazeta Wyborcza.[63]

2001 was the year the first Equality Parade was held in Warsaw, attended by over 300 people. This was the first large-scale protest against homosexual discrimination. That same year Campaign Against Homophobia was established.[26] A campaign, Niech nas zobaczą, (Let Them See Us) was held in 2003. It was the first artistic social campaign against homophobia, and consisted of 30 photos by Karolina Breguła. These showed gay and lesbian couples and were exhibited at exhibitions in galleries and printed on billboards, which were often vandalized.[67] In 2004 and 2005 officials denied permission for the Warsaw Pride Parade, citing the likelihood of counter-demonstrations, interference with religious or national holidays, lack of a permit, among other reasons.[68] The parade was opposed by the conservative Law and Justice party's Lech Kaczyński (at the time mayor of Warsaw and later president of Poland) who said that allowing an official gay pride event in Warsaw would promote a homosexual lifestyle.[69] In protest, a different event, Wiec Wolności (Freedom Veche), was organized in Warsaw in 2004,[70] and was estimated to have drawn 600 to 1000 attendees.[71] In response to the 2005 ban, about 2500 people marched on 11 June of that year, in an act of civil disobedience that led to several brief arrests.[72] By entering European Union, Poland had to fully incorporate anti-discrimination laws into its legal structure, including those dealing with discrimination for sexual orientation. On 1 January 2004, a law that included forbidding workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation became part of Polish labour laws.[26]

In 2011 election Poland made history by electing its first out LGBT Members of Parliament—Robert Biedroń, an out gay man, and Anna Grodzka, an out transgender woman, one of the originators of foundation Trans-Fuzja.[66]

Since 2015

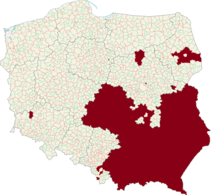

While ahead of the 2015 Polish parliamentary election, the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party took an anti-migrant stance, in the run-up to the 2019 Polish parliamentary election the party has focused on countering Western "LGBT ideology".[73] Several Polish municipalities and four Voivodeships made so-called "LGBT-free zone" declarations, partly in response to the signing of a declaration in support of LGBTQ rights by Warsaw mayor Rafał Trzaskowski.[73][76] While only symbolic, the declared zones signal exclusion of the LGBT community. The right wing Gazeta Polska newspaper issued "LGBT-free zone" stickers to readers.[77] The Polish opposition and diplomats, including US ambassador to Poland Georgette Mosbacher, condemned the stickers.[78][79] The Warsaw district court ordered that distribution of the stickers should halt pending the resolution of a court case.[80] However Gazeta's editor dismissed the ruling saying it was "fake news" and censorship, and that the paper would continue distributing the sticker.[81] Gazeta continued with the distribution of the stickers, but modified the decal to read "LGBT Ideology-Free Zone".[80]

In August 2019, multiple LGBT community members have stated that they feel unsafe in Poland. Foreign funded NGO All Out organization launched a campaign to counter the attacks, with about 10,000 people signing a petition shortly after the campaign launch.[82] 2019 saw a rise of violence directed against Pride marches, including the attacks at the first Białystok Equality March[83][84] and a bombing attempt made at a Lublin march, stopped by the police.[85][86]

In the 2020 Polish presidential election, President Andrzej Duda focused heavily on LGBT issues, stating "LGBT is not people, it's an ideology, which is more harmful than Communism". He narrowly won re-election.[87][88] According to ILGA-Europe's 2020 report, Poland is ranked worst among European Union countries for LGBT rights.[89] On 7 August 2020, 47 people were arrested in the Rainbow Night mass arrest. Some of them were peacefully protesting the arrest of Margot, an LGBT activist, while others were passerby.[90] The Polish Ombudsman criticized human rights violations by the police.[91]

On 27 September, 50 Ambassadors and Representatives from all over the world (included: the Representatives in Poland of the European Commission and of the UNHCR, the First Deputy Director of the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, the Head of Office of the International Organization for Migration, the Secretary General of the Community of Democracies) published an open letter to the Polish authorities called "Human Rights are not an ideology - they are universal. 50 Ambassadors and Representatives agree."[92][93] and giving their support of the efforts of LGBT people equal rights, the respect of fundamental human rights, the need to protect from verbal and physical abuse and hate speech; ending with the text on the bottom:

Human rights are universal and everyone, including LGBTI persons, are entitled to their full enjoyment.[92][94]

On November 11, 2021, while Polish far-right nationalists at a rally in Kalisz attended by hundreds of people yelled "Death to Jews," the rally organizer said: “LGBT, pederasts and Zionists are the enemies of Poland.”[95][96]

On 27 December 2023, Prime Minister Donald Tusk announced that a bill to legalise same-sex unions would be introduced and debated in the Sejm in early 2024, in line with a pledge made during his campaign in the 2023 election.[97] The bill was added to the government agenda on 8 July 2024 and presented publicly by Minister of Equality Katarzyna Kotula in October 2024.[98] It would allow both opposite-sex and same-sex couples to form registered partnerships, affording rights in the areas of inheritance, property, taxation and support, but would not allow registered partners to adopt.[99] Civic Platform and The Left have vowed to pass the bill.[100] In October, the Archbishop of Warsaw, Kazimierz Nycz, expressed his support for civil partnerships and said "that the Church will not interfere in the legislative process".[101] A public consultation process was open until 15 November 2024.[102][103]

On 6 December 2024, nonprofit group Lambda opened Queer Museum in Warsaw, first of its kind in Central and Eastern Europe, showcasing the history of LGBTQ people living in Poland.[104][105][106]

See also

- Rainbow Night – 2020 mass arrest of LGBT rights protesters in Poland

- LGBTQ-free zone

- LGBTQ rights in Poland

- List of LGBTQ politicians in Poland

- Political activity of the Catholic Church on LGBT issues in Poland

Notes

- ^ They were established and governed on the basis of the location privilege known as the "settlement with German law"

References

- ^ Szulc, Lukasz; Springer International Publishing AG (2018). Transnational Homosexuals in Communist Poland Cross-Border Flows in Gay and Lesbian Magazines. Springer. pp. 8, 97. ISBN 978-3-319-58901-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "GLBTQ" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ "Where is it illegal to be gay?". BBC News. 10 February 2014. Archived from the original on 23 February 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ "LGBT Rights in Poland". Equaldex. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Ivakhiv, Adrian (2005). "The Revival of Ukrainian Native Faith". In Michael F. Strmiska (ed.). Modern Paganism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 209–239. ISBN 9781851096084.

- ^ Ebner, Adalabert "Die klösterlichen Gebets-Verbrüderungen bis zum Ausgange des karolingischen Zeitalters. Eine kirchengeschichtliche Studie" (1890).

- ^ Christopher Isherwood, Christopher and His Kind 1929-1939 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976), 137.

- ^ Tih R Georgevitch., "Serbian Habits and Customs," Folklore 28:1 (1917) 47

- ^ M. E. Durham, Some Tribal Origins, Laws and Customs of the Balkans (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1928) 174

- ^ a b Naumow, Aleksander; KAszlej, Andrzej (2004). Rękopisy cerkiewnosłowiańskie w Polsce (PDF). Scriptum. ISBN 9788391981443. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ Fijałkowski, Paweł (2009). Homoseksualizm: wykluczenie, transgresja, akceptacja (in Polish). Eneteia - Wydawnictwo Psychologii i Kultury. ISBN 9788361538080.

- ^ Kracik J., Rożek M., Hultaje, złoczyńcy, wszetecznice w dawnym Krakowie : o marginesie społecznym XVI-XVIII w., Kraków 1986, s. 53

- ^ Tazbir J., Staropolskie dewiacje obyczajowe, s.9

- ^ Pękacka-Falkowska, Katarzyna (31 May 2015). "Bawarski obojnak z "Efemerydów", czyli o tajemnicy płci". www.wilanow-palac.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Oczko P., Nastulczyk T., Homoseksualność staropolska: przyczynek do badań, Kraków 2012, s. 280

- ^ Leon Wachholz, Obojnak przed sądem w Kazimierzu R. P. 1561. Przyczynek do dziejów obojnactwa, „Przegląd Lekarski”, L, 1911, nr 10.

- ^ Oczko P., Nastulczyk T., Homoseksualność staropolska: przyczynek do badań, Kraków 2012, s. 277

- ^ Wiślicz T., Z zagadnień obyczajowości seksualnej chłopów ..., s. 57-58

- ^ Kuchowicz Z., Człowiek polskiego baroku, Łódź 1992, s. 319

- ^ Kuchowicz Z., Człowiek polskiego baroku, Łódź 1992, s. 321

- ^ Tazbir J., Staropolskie dewiacje obyczajowe [w:] "Przegląd historyczny" nr 7/8 1985, s. 13

- ^ a b c "Dlaczego nie chcę pisać o staropolskich samcołożnikach? Przyczynek do "archeologii" gay studies w Polsce" (PDF) (in Polish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ . J. Kitowicz Pamiętniki czyli Historia Polska, oprac. i wstęp P. Matuszewska, kom. Z. Lewinówna, PIW, Warszawa 2005, s. 63-64.

- ^ Kaleta, Roman (1971). Oświeceni i sentymentalni: studia nad literaturą i życiem w Polsce w okresie trzech rozbiorów (in Polish). Wrocław: Ossolineum. OCLC 604024003.

- ^ Tazbir J., Staropolskie dewiacje obyczajowe [w:] "Przegląd historyczny" nr 7/8 1985, s. 11

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z "Queer Studies. Podręcznik kursu" (PDF). Kampania Przeciw Homofobii. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ Prawa mniejszości seksualnych – prawami człowieka, "Biblioteczka Pełnomocnika Rządu ds. Równego Statusu Kobiet i Mężczyzn", zeszyt 5, Warszawa, 2003, s. 59

- ^ a b c d Tomasik, Krzysztof (2014). Homobiografie. Wydawn. Krytyki Politycznej. ISBN 978-83-64682-22-3. OCLC 915574182.

- ^ Kuczalska-Reinschmit, Paulina; Zawiszewska, Agata (2012). Nasze drogi i cele : prace o działalności kobiecej. Zawiszewska, Agata (Wydanie 1 ed.). Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Feminoteki. ISBN 978-83-62206-56-8. OCLC 868987902.

- ^ Maria Dernałowicz (1977), "Piotr Odmieniec Włast", Twórczość, no. 3, pp. 79–95

- ^ Tuszyńska A., Krzywicka. Długie życie gorszycielki, Wydawnictwo Literackie, Warszawa, 2009, s. 18.

- ^ Kydryński L., Opera na cały rok. Kalendarium, tom 1, Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne, 1989

- ^ Pająk, Paulina (2 January 2022). "1933: the year of lesbian modernism in Poland?". Women's History Review. 31 (1): 28–50. doi:10.1080/09612025.2021.1954333. ISSN 0961-2025.

- ^ a b Karczewski, Kamil. "Cioty z placu Napoleona". www.dwutygodnik.com (in Polish). Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Karczewski, Kamil (September 2022). ""Call Me by My Name:" A "Strange and Incomprehensible" Passion in the Polish Kresy of the 1920s". Slavic Review. 81 (3): 631–652. doi:10.1017/slr.2022.224. hdl:1814/75389. ISSN 0037-6779.

- ^ Szot, Wojciech (6 February 2013). "homiki.pl :artykuł : Kto wyśledzi Meklenburga?". homiki.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Szot, Wojciech (2020). Panna doktór Sadowska. Warszawa. ISBN 978-83-65970-41-1. OCLC 1227934496. Archived from the original on 26 July 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Marek Teler (30 November 2020). "Kobieta, która stała się mężczyzną". Replika. Warszawa: Fundacja Replika. ISSN 1896-3617. OCLC 759913113. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ Ostrowska, Joanna. "Publiczne pudrowanie nosa". www.dwutygodnik.com (in Polish). Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d Ostrowska, Joanna (2021). Oni: homoseksualiści w czasie II wojny światowej. Seria Historyczna (Wydanie pierwsze ed.). Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej. ISBN 978-83-66586-58-1. OCLC 1261283578.

- ^ Ostrowska, Joanna (1 April 2022). "Dobry Staś". Replika Online (in Polish). Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ "Poszukiwani, poszukiwane. Geje i lesbijki a rzeczywistość PRL" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ Snijders, Tim Igor. "Communist Poland's hidden queer history". Iron Curtain Project. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ Krzysztof Tomasik (2018). Gejerel : mniejszości seksualne w PRL-u (in Polish). Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej. ISBN 978-83-65853-53-0. OCLC 1050782877.

- ^ Imieliński, Kazimierz; Dulko, Stanisław (1989). Apokalipsa płci. Szczecin: Glob. pp. 202–233. ISBN 83-7007-224-0. OCLC 749261787. Archived from the original on 26 July 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ "Wielcy i niezapomiani: Jerzy Zawieyski". queer.pl. 17 December 2004. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ HOSI, "Inaczej", nr 12, maj 1991 r., s. 7

- ^ Postscriptum do "Wspomnień Weterana", "Inaczej", nr 13, czerwiec 1991 r., s. 3.

- ^ Warkocki, Błażej (2014). "Trzy fale emancypacji homoseksualnej w Polsce". Porównania. 15: 121. doi:10.14746/p.2014.15.10896. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ "AIDS - kronika zarazy". www.e-teatr.pl. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ "Teatr w Polsce - polski wortal teatralny". www.e-teatr.pl. Archived from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ "FilmPolski.pl". FilmPolski (in Polish). Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ "Człowiek, który rzucił wyzwanie AIDS". www.e-teatr.pl. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- ^ a b Zielinska, Iwona. "Who is afraid of sexual minorities? Homosexuals, moral panic and the exercise of social control" (PDF). University of Sheffield. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "What to do with "pink files"?". Queer (in Polish). 14 August 2004. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Wspomnienia weterana, "Inaczej", nr 9, luty 1991 r., s. 3.

- ^ Kostrzewa, Yga; Minałto, Michał; Pietras, Marcin; Szot, Wojciech; Teodorczyk, Marcin; Tomasik, Krzysztof; Zabłocki, Krzysztof; Pietras, Marcin (2010). QueerWarsaw. Historical and cultural guide to Warsaw (whole issue). Translated by Mateusz Urban; et al. Warsaw: Stowarzyszenie Lambda Warszawa. pp. 201–204. ISBN 978-83-926968-1-0. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013. (pages 201-204) Archived 2016-08-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pierre Noël (February 1988). "Nouvelles de Pologne" (in French). Tels Quels Magazine (Belgium). Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ Franz Werner (June 1988). "Pedal in Polen" (in German). Rosa Flieder (Germany). Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ Andrzej Selerowicz (2010). Leksykon kochających inaczej (in Polish). Poznań: Wydawnictwo SOFTPRESS. pp. 19–28. ISBN 978-83-900208-6-0. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ Jiří Pehe (17 November 1988). "Independent Movements in Eastern Europe, page 18, (RAD BR/228)". osaarchivum.org. Blinken Open Society Archives. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

The Warsaw Homosexual Movement. Founded: Date unknown in Warsaw; has been told unofficially that it will be legalized this year as an independent association. Estimated membership: "A few hundred." Objectives: No aims stated. Leading personalities: Waldemar Zboralski.

- ^ Jiří Pehe (13 June 1989). "An Annotated Survey of Independent Movements in Eastern Europe, page 28, (RAD BR/100)". osaarchivum.org. Blinken Open Society Archives. Archived from the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d Tomasik K ., 20 lat polskiego ruchu LGBT, "Replika", 05/06 2009, nr 19, s 17

- ^ "ArtPapier". artpapier.com. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ "Polskie coming outy: Marek Barbasiewicz". Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ a b "O HISTORII RUCHU LGBT W POLSCE". 9 September 2013. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ "Niech nas zobaczą : Homoseksualizm: geje, lesbijki - zobacz ich!". 8 May 2012. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012.

- ^ Townley, Ben (20 May 2005). "Polish capital bans Pride again". Gay.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007.

- ^ Gay marchers ignore ban in Warsaw Archived 20 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News Online, 11 June 2005

- ^ "Krótka historia Parady Równości | Parada Równości". Paradarownosci.eu. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ "Wiec Wolności". Mediateka.ngo.pl. 11 February 2010. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ "Europe | Gay marchers ignore ban in Warsaw". BBC News. 11 June 2005. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ a b c Polish towns advocate ‘LGBT-free’ zones while the ruling party cheers them on Archived 14 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Washington Post, 21 July 2019, reprint at Independent Archived 25 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Gdzie w Polsce przyjęto uchwały przeciw "ideologii LGBT"?" [Where in Poland were the resolutions adopted against "LGBT ideology"?]. Onet Lublin (in Polish). ONET. 23 July 2019. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ Figlerowicz, Marta (9 August 2019). "The New Threat to Poland's Sexual Minorities". Foreign Affairs: America and the World. ISSN 0015-7120. Archived from the original on 25 April 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ Polish ruling party whips up LGBTQ hatred ahead of elections amid 'gay-free' zones and Pride march attacks Archived 14 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Telegraph, 9 August 2019

- ^ Polish newspaper to issue 'LGBT-free zone' stickers Archived 26 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 18 July 2019

- ^ Anti-Gay Brutality in a Polish Town Blamed on Poisonous Propaganda Archived 8 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, New York Times, 27 July 2019

- ^ Conservative Polish magazine issues 'LGBT-free zone' stickers Archived 14 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 24 July 2019

- ^ a b Polish Court Rebukes "LGBT-Free Zone" Stickers Archived 7 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine, HRW, 1 August 2019

- ^ Polish magazine dismisses court ruling on ‘LGBT-free zone’ stickers Archived 27 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Politico, 26 July 2019

- ^ Activists warn Poland’s LGBT community is 'under attack' Archived 26 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Euronews, 8 August 2019

- ^ Santora, Marc; Berendt, Joanna (27 July 2019). "Anti-Gay Brutality in a Polish Town Blamed on Poisonous Propaganda". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Tara John; Muhammad Darwish (21 July 2019). "Polish city holds first LGBTQ pride parade despite far-right violence". CNN. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ "Couple Arrested Over Explosive Device at Polish Pride Parade". Instinct Magazine. 6 October 2019. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ "Poland: as government's anti-LGBTQ+ campaign intensifies, homophobes bring bomb to Pride March". Freedom News. 4 October 2019. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ^ Pronczuk, Monika (30 July 2020). "Polish Towns That Declared Themselves 'L.G.B.T. Free' Are Denied E.U. Funds". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Dellanna, Alessio (15 June 2020). "LGBT campaigners denounce President Duda's comments on "communism"". euronews. Archived from the original on 27 August 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ "Country Ranking | Rainbow Europe". rainbow-europe.org. Archived from the original on 14 May 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ "Polish Stonewall? Protesters decry government's anti-LGBTQ Attitudes". ABC News. Associated Press. 10 August 2020. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Ciobanu, Claudia (13 August 2020). "Mass Arrest of LGBT People Marks Turning Point for Poland". Balkan Insight. Archived from the original on 17 September 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Open Letter - Human Rights are not an ideology - they are universal. 50 Ambassadors and Representatives agree". pl.usembassy.gov. 27 September 2020. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Bix Aliu [@USAmbPoland] (27 September 2020). "Human Rights are not an ideology - they are universal. 50 Ambassadors and Representatives agree" (Tweet). Retrieved 12 March 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ "List ambasadorów. "Wyrażamy uznanie dla ciężkiej pracy społeczności LGBTI w Polsce"". wyborcza.pl. 27 September 2020. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020.

- ^ "Poland: Chanting 'death To Jews,' Far-right Nationalists Burn Book On Jewish Rights". I24news. 23 November 2021.

- ^ Tilles, Daniel (12 November 2021). ""Death to Jews" chanted at torchlit far-right march in Polish city".

- ^ "Tusk zapowiedział ustawę o związkach partnerskich". www.rmf24.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ "Polish government presents bill introducing same-sex partnerships". 19 October 2024.

- ^ "Bill introducing same-sex civil partnerships in Poland added to government agenda". 9 July 2024.

- ^ "Znamy kluczowe założenia ustawy o związkach partnerskich!". Zaimki (in Polish). 25 September 2024.

- ^ "Polish Catholic Church supports civil partnerships, but not equating them to marriage". Polskie Radio. 24 October 2024.

- ^ "Żołnierka: Nikt nie wziął pod uwagę, że mam partnerkę [Ustawa o związkach partnerskich]". OKO.press (in Polish). 9 November 2024.

- ^ "Co dalej z ustawami o związkach partnerskich? Posłanka PSL: nie ma tak wielu różnic". Wiadomości (in Polish). 20 November 2024.

- ^ Villa, Angelica (9 December 2024). "Warsaw Non-Profit Opens First Museum of Queer History in Poland". ARTnews.com. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ Ciobanu, Claudia (17 December 2024). "First Queer Museum in CEE Opens in Poland". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ "Poland's first queer museum opens its door - English Section". Polskie Radio. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

Further reading

- Austermann, Julia (2021). Visualisierungen des Politischen: Homophobie und queere Protestkultur in Polen ab 1980 (in German). transcript Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8394-5403-9.