John William Waterhouse

John William Waterhouse | |

|---|---|

Waterhouse, c. 1886 | |

| Born | |

| Baptised | 6 April 1849 [1] |

| Died | 10 February 1917 (aged 68) |

| Nationality | British |

| Works | Hylas and the Nymphs The Lady of Shalott The Magic Circle Ophelia A Mermaid |

| Movement | Pre-Raphaelite |

| Spouse | Esther Kenworthy Waterhouse |

John William Waterhouse RA (baptised 6 April 1849 – 10 February 1917) was an English painter known for working first in the Academic style and for then embracing the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood's style and subject matter. His paintings are known for their depictions of women from both ancient Greek mythology and Arthurian legend. A high proportion depict a single young and beautiful woman in a historical costume and setting, though there are some ventures into Orientalist painting and genre painting, still mostly featuring women.

Born in Rome to English parents who were both painters, Waterhouse later moved to London, where he enrolled in the Royal Academy of Art Schools. He soon began exhibiting at their annual summer exhibitions, focusing on the creation of large canvas works depicting scenes from the daily life and mythology of ancient Greece. Many of his paintings are based on authors such as Homer, Ovid,[2] Shakespeare, Tennyson, or Keats.

Waterhouse's work is displayed in many major art museums and galleries, and the Royal Academy of Art organised a major retrospective of his work in 2009.

Biography

Early life

Waterhouse was born in the city of Rome to the English painters William and Isabella Waterhouse in 1849, in the same year that the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt, were first causing a stir in the London art scene.[3] The exact date of his birth is unknown, though he was baptised on 6 April, and the later scholar of Waterhouse's work, Peter Trippi, believed that he was born between 1 and 23 January.[1] His early life in Italy has been cited as one of the reasons many of his later paintings were set in ancient Rome or based upon scenes taken from Roman mythology.

In 1854, the Waterhouses returned to England and moved to a newly built house in South Kensington, London, which was near to the newly founded Victoria and Albert Museum. Waterhouse, or 'Nino' as he was nicknamed, coming from an artistic family, was encouraged to become involved in drawing, and often sketched artworks that he found in the British Museum and the National Gallery.[4] In 1871, he entered the Royal Academy of Art school, initially to study sculpture, before moving on to painting.

Early career

Waterhouse's early works were not Pre-Raphaelite in nature, but were of classical themes in the spirit of Alma-Tadema and Frederic Leighton. These early works were exhibited at the Dudley Gallery, and the Society of British Artists, and in 1874 his painting Sleep and his Half-brother Death was exhibited at the Royal Academy summer exhibition.[5] The painting was a success and Waterhouse would exhibit at the annual exhibition every year until 1916, with the exception of 1890 and 1915. He then went from strength to strength in the London art scene, his 1876 piece After the Dance being given the prime position in that year's summer exhibition. Perhaps due to his success, his paintings typically became larger.[5]

Later career

In 1883, Waterhouse married Esther Kenworthy, the daughter of an art schoolmaster from Ealing who had exhibited her own flower-paintings at the Royal Academy and elsewhere. In 1895 Waterhouse was elected to the status of full Academician. He taught at the St. John's Wood Art School, joined the St John's Wood Arts Club, and served on the Royal Academy Council.

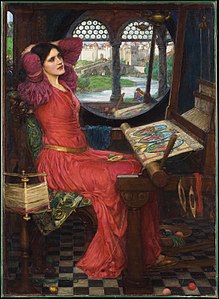

One of Waterhouse's best known subjects is The Lady of Shalott, a study of Elaine of Astolat as depicted in the 1832 poem by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, who dies of a mysterious curse after looking directly at the beautiful Lancelot. He actually painted three different versions of this character, in 1888, 1894, and 1916. Another of Waterhouse's favorite subjects was Ophelia; the most familiar of his paintings of Ophelia depicts her just before her death, putting flowers in her hair as she sits on a tree branch leaning over a lake. Like The Lady of Shalott and other Waterhouse paintings, it deals with a woman dying in or near water. He may also have been inspired by paintings of Ophelia by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais.

He submitted his 1888 Ophelia painting in order to receive his diploma from the Royal Academy. (He had originally wanted to submit a painting titled A Mermaid, but it was not completed in time.) After this, the painting was lost until the 20th century. It is now displayed in the collection of Lord Lloyd-Webber. Waterhouse would paint Ophelia again in 1894 and 1909 or 1910, and he planned another painting in the series, called Ophelia in the Churchyard.

Waterhouse could not finish the series of Ophelia paintings because he was gravely ill with cancer by 1915. He died two years later, and his grave can be found at Kensal Green Cemetery in London.[6]

Gallery

In total, he produced 118 paintings. See List of paintings by John William Waterhouse for an almost complete list.

1870s

-

Undine

1872 -

Gone, But Not Forgotten

1873 -

La Fileuse

1874 -

In the Peristyle

1874 -

Miranda

1875 -

After the Dance

1876 -

A Sick Child brought into the Temple of Aesculapius

1877 -

The Remorse of the Emperor Nero after the Murder of his Mother

1878

1880s

-

Dolce far Niente

1880 -

Diogenes

1882 -

Saint Eulalia

1885 -

The Magic Circle

1886 -

Mariamne Leaving the Judgement Seat of Herod

1887 -

Cleopatra

1888 -

Ophelia

1889

1890s

-

A Roman Offering

1890 -

Danaë

1892 -

Circe Invidiosa

1892 -

Gathering Summer Flowers in a Devonshire Garden

1892-1893 -

A Female Study

1894 -

Ophelia

1894 -

The Shrine

1895 -

Saint Cecilia

1895 -

Pandora

1896 -

Juliet

1898 -

Ariadne

1898

1900s

-

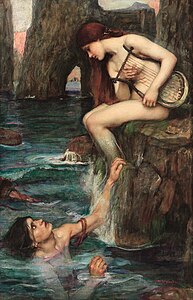

The Siren

1900 -

Destiny

1900 -

The Lady Clare

1900 -

Study for Nymphs Finding the Head of Orpheus

1900 -

Nymphs Finding the Head of Orpheus

1900 -

The Mermaid

1901 -

The Crystal Ball

1902 -

The Missal

1902 -

Windflowers

1902 -

Boreas

1903 -

Psyche Opening the Golden Box

1903 -

Psyche Opening the Door into Cupid's Garden

1904 -

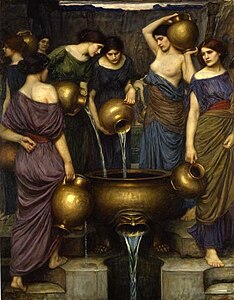

The Danaides, 1906

-

Jason and Medea

1907 -

Isabella and the pot of basil

1907 -

The Bouquet

(a study)

1908 -

Gather Ye Rosebuds or Ophelia (a study)

c. 1908 -

The Soul of the Rose or My Sweet Rose

1908 -

Lamia

(version 2)

1909 -

Thisbe

1909

1910s

-

Ophelia

1910 -

Spring Spreads One Green Lap of Flowers

1910 -

The Charmer

1911 -

Penelope and the Suitors

1912 -

The Annunciation

1914 -

Dante and Matilda (study) (formerly called "Dante and Beatrice")

c. 1914–17 -

Matilda (study) (formerly called "Beatrice")

c. 1915 -

A Tale from the Decameron

1916 -

Tristan and Isolde

1916

References

Notes

- ^ a b Trippi 2002, p. 9.

- ^ Severino, Carlos Mesquita (2019). Representações das Metamorphoses de Ovídio em J. W. Waterhouse (masterThesis). Lisboa: Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa.

- ^ Trippi 2002, p. 4.

- ^ Trippi 2002, p. 14.

- ^ a b Trippi, Peter; Prettejohn, Elizabeth; Upstone, Robert. J.M. Waterhouse: The Modern Pre-Raphaelite Gallery Guide. The Royal Academy of Art. 2009.

- ^ J.W. Waterhouse and the Magic of Color

Bibliography

- Trippi, Peter (2002). J. W. Waterhouse. New York, New York: Phaidon Press. ISBN 9780714842325.

Further reading

- Baldry, A. Lys (January 1895), J. W. Waterhouse and his Work, vol. 4, pp. 103–115

- Bénézit, E (2006). "Waterhouse, John William". Dictionary of Artists. Vol. 14. Paris: Gründ. pp. 668–669.

- Dorment, Richard (29 June 2009), "Waterhouse: The modern Pre-Raphaelite, at the Royal Academy – review", The Daily Telegraph

- Gunzburg, Darrelyn (2010). "John William Waterhouse, Beyond the Modern Pre-Raphaelite". The Art Book. 17 (2): 70–72. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8357.2010.01104.x. ISSN 1368-6267.

- Hobson, Anthony (1980). The Art and Life of J.W. Waterhouse, RA, 1849-1917. Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0-8478-0324-8.

- Moyle, Franny (13 June 2009), "Pre-Raphaelite art: the paintings that obsessed the Victorians [print version: Sex and death: The paintings that obsessed the Victorians]", The Daily Telegraph (Review), pp. R2–R3.

- Simpson, Eileen (17 June 2009), "Pre-Raphaelites for a new generation: Letters, 17 June: Pre-Raphaelite revival", The Daily Telegraph.

- Cartwright, Rob (2021), TURNING THE LIGHT ON J.W. WATERHOUSE, RA – A BIOGRAPHY

External links

- John William Waterhouse.net

- John William Waterhouse (The Art and Life of JW Waterhouse) Archived 14 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine;

- John William Waterhouse (Comprehensive Painting Gallery)

- John William Waterhouse (1849–1917)

- John William Waterhouse Style and Technique

- Waterhouse at Tate Britain

- Echo and Narcissus (1903)

- Ten Dreams Galleries

- John William Waterhouse in the "History of Art"

- Profile on Royal Academy of Arts Collections

- 25 artworks by or after John William Waterhouse at the Art UK site

- Portraits of John William Waterhouse at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Trippi, Peter. "Waterhouse, John William (1849–1917)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/38885. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Waterhouse, John William". Who's Who. A & C Black. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- John William Waterhouse at Library of Congress, with 2 library catalogue records

- Findagrave burial record