Ismail Khan

Ismail Khan | |

|---|---|

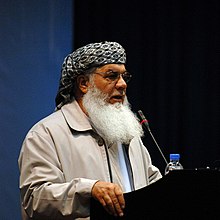

Ismail Khan at the 2010 National Conference on Water Resources, Development and Management of Afghanistan | |

| Minister of Energy and Water | |

| In office 2004 – October 2013 | |

| President | Hamid Karzai |

| Succeeded by | Mohammad Arif Noorzai |

| Governor of Herat Province | |

| In office 2001 – 12 September 2004 | |

| President | Hamid Karzai |

| Preceded by | Mulla Yaar Mohammad |

| Succeeded by | Sayed Mohammad Khairkhah |

| In office 1992–1997 | |

| Succeeded by | Mullah Yaar Mohammad |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1946 (age 77–78) Shindand, Herat Province, Kingdom of Afghanistan |

| Political party | Jamiat-e-Islami |

| Occupation | Politician, former Mujahideen leader |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Afghan Army (1967‐79) |

| Years of service | 1967-2021 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars | |

Mohammad Ismail Khan (Dari/Pashto: محمد اسماعیل خان) (born 1946) is an Afghan former politician who served as Minister of Energy and Water from 2005 to 2013 and before that served as the governor of Herat Province. Originally a captain in the Afghan Army, he is widely known as a former warlord who controlled a large mujahideen force, mainly his fellow Tajiks from western Afghanistan, during the Soviet–Afghan War.[1]

His reputation gained him the nickname Lion of Herat.[2] Ismail Khan was a key member of the now exiled political party Jamiat-e Islami and of the now defunct United National Front party.[3] In 2021, Ismail Khan returned to arms to help defend Herat from the Taliban's offensive, which he and the Afghan Army lost.[4] He was captured by the Taliban forces[5][6][7] and then reportedly fled to Iran on 16 August 2021.[8][9]

Early years and rise to power

Khan was born in 1946 in the Shindand District of Herat Province in Afghanistan and his family is from the Chahar-Mahal neighbourhood of Shindand.

In early 1979 Ismail Khan was a captain in the Afghan National Army based in the western city of Herat. In early March of that year, there was a protest in front of the Communist governor's palace against the arrests and assassinations being carried out in the countryside by the Khalq government. The governor's troops opened fire on the demonstrators, who proceeded to storm the palace and hunt down Soviet advisers. The Herat garrison mutinied and joined the revolt in what is called the Herat uprising, with Ismail Khan and other officers distributing all available weapons to the insurgents. The government led by Nur Mohammed Taraki responded, pulverizing the city using Soviet supplied bombers and killing up to 24,000 citizens in less than a week.[10] This event marked the opening salvo of the rebellion which led to the Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan in December 1979. Ismail Khan escaped to the countryside where he began to assemble a local rebel force.[11]

During the ensuing war, he became the leader of the western command of Burhanuddin Rabbani's Jamiat-e-Islami, political party. With Ahmad Shah Massoud, he was one of the most respected mujahideen leaders.[10] In 1992, three years after the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, the mujahideen captured Herat and Ismail Khan became governor.

In 1995, he successfully defended his province against the Taliban, in cooperation with defense minister Ahmad Shah Massoud. Khan even tried to attack the Taliban stronghold of Kandahar, but was repulsed. Later in September, an ally of the Jamiat, Uzbek General Abdul Rashid Dostum changed sides, and attacked Herat. Ismail Khan was forced to flee to neighboring Iran with 8,000 men and the Taliban took over Herat Province.

Two years later, while organizing opposition to the Taliban in Faryab area, he was betrayed and captured by Abdul Majid Rouzi who had defected to the Taliban along with Abdul Malik Pahlawan, then one of Dostum's deputies.[10] Then in March 1999 he escaped from Kandahar prison. During the U.S. intervention in Afghanistan, he fought against the Taliban within the United Islamic Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan (Northern Alliance) and thus regained his position as Governor of Herat after they were victorious in December 2001.

Karzai administration and return to Afghanistan

After returning to Herat, Ismail Khan quickly consolidated his control over the region. He took over control of the city from the local ulema and quickly established control over the trade route between Herat and Iran, a large source of revenue.[12] As Emir of Herat, Ismail Khan exercised great autonomy, providing social welfare for Heratis, expanding his power into neighbouring provinces, and maintaining direct international contacts.[13] Although hated by the educated in Herat and often accused of human rights abuses, Ismail Khan's regime provided security, paid government employees, and made investments in public services.[14] However, during his tenure as governor, Ismail Khan was accused of ruling his province like a private fiefdom, leading to increasing tensions with the Afghan Transitional Administration. In particular, he refused to pass on to the government the revenues gained from custom taxes on goods from Iran and Turkmenistan.

On 13 August 2003, President Karzai removed Governor Ismail Khan from his command of the 4th Corps. This was announced as part of a programme removing the ability of officials to hold both civilian and military posts.

Ismail Khan was ultimately removed from power in March 2004 due to pressure by neighbouring warlords and the central Afghan government. Various sources have presented different versions of the story, and the exact dynamics cannot be known with certainty. What is known is that Ismail Khan found himself at odds with a few regional commanders who, although theoretically his subordinates, attempted to remove him from power. Ismail Khan claims that these efforts began with a botched assassination attempt. Afterwards, these commanders moved their forces near Herat. Ismail Khan, unpopular with the Herati military class, was slow to mobilise his forces, perhaps waiting for the threat to Herat to become existential as a means to motivate his forces. However, the conflict was stopped with the intervention of International Security Assistance Force forces and soldiers of the Afghan National Army, freezing the conflict in its tracks. Ismail Khan's forces even fought skirmishes with the Afghan National Army, in which his son, Mirwais Sadiq was killed. Because Ismail Khan was contained by the Afghan National Army, the warlords who opposed him were quickly able to occupy strategic locations unopposed. Ismail Khan was forced to give up his governorship and to go to Kabul, where he served in Hamid Karzai's cabinet as the Minister of Energy.[15]

In 2005 Ismail Khan became the Minister of Water and Energy.

In late 2012, the Government of Afghanistan accused Ismail Khan of illegally distributing weapons to his supporters.[16] About 40 members of the country's Parliament requested Ismail Khan to answer their queries. The government believes that Khan is attempting to create some kind of disruption in the country.[1][17]

Assassination attempt

On September 27, 2009, Ismail Khan survived a suicide blast that killed 4 of his bodyguards in Herat, in western Afghanistan. He was driving to Herat Airport when a powerful explosion occurred close to his convoy of vehicles. Taliban spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid claimed responsibility and said Khan was the target.[18]

Testimony requested by a Guantanamo captive

Guantanamo captive Abdul Razzaq Hekmati requested Ismail Khan's testimony, when he was called before a Combatant Status Review Tribunal.[19] Ismail Khan, like Afghan Minister of Defense Rahim Wardak, was one of the high-profile Afghans that those conducting the Tribunals ruled were "not reasonably available" to give a statement on a captive's behalf because they could not be located.

Hekmati had played a key role in helping Ismail Khan escape from the Taliban in 1999.[20] Hekmati stood accused of helping Taliban leaders escape from the custody of Hamid Karzai's government.

Carlotta Gall and Andy Worthington interviewed Ismail Khan for a new The New York Times article after Hekmati died of cancer in Guantanamo.[20] According to the New York Times Ismail Khan said he personally buttonholed the American ambassador to tell him that Hekmati was innocent, and should be released. In contrast, Hekmati was told that the State Department had been unable to locate Khan.

2021 Taliban offensive and capture

In July 2021, Ismail Khan mobilized hundreds of his loyalists in Herat in support of the Afghan Armed Forces to defend the city from an offensive by the Taliban.[21] Despite this, the city fell on 12 August 2021.[22][23][24] After trying to escape by helicopter, Khan was captured by the Taliban.[22][23][24] The Taliban interviewed him shortly after and claimed that he and his forces have joined them.[24][25] After negotiating with the Taliban, he was allowed to return to his residence.[26]

After leaving Taliban custody, as of August 2021 Khan is living in Mashhad, Iran.[27] He said that a conspiracy was responsible for Herat being captured by the Taliban.[9]

Controversy

Ismail Khan is a controversial figure. Reporters Without Borders has charged him with muzzling the press and ordering attacks on journalists.[28] Also Human Rights Watch has accused him of human rights abuses.[29]

Nevertheless, he remains a popular figure for some in Afghanistan. Unlike other mujahideen commanders, Khan has not been linked to large-scale massacres and atrocities such as those committed after the capture of Kabul in 1992.[10] Following news of his dismissal, rioting broke out in the streets of Herat, and President Karzai had to ask him to make a personal appeal for calm.[30]

Notes and references

- ^ a b "Afghan warlord's call to arms rattles officials".

- ^ "Afghan warlord Ismail Khan, known as 'Lion of Herat', detained by Taliban as his city falls to insurgents". 13 August 2021.

- ^ Williams, Brian Glyn (2012). Afghanistan declassified : a guide to America's longest war (1st ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, 2011. pp. 29–30. ISBN 9780812206159. OCLC 793012539.

- ^ "On the front line in Afghanistan with Ismail Khan, the 'Lion of Herat'". Independent.co.uk. 9 August 2021.

- ^ Hassan, Sharif (13 August 2021). "An Afghan warlord who steadfastly resisted the Taliban surrendered. Others may follow his lead". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ "Former Herat governor and Afghan chief Ismail Khan has joined the Taliban with supporters". Nation World News. 13 August 2021. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ "Ismail Khan joins Islamic Emirate with all his supporters and troops – Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan". Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ Jaafari, Shirin (16 August 2021). "Former warlord Ismail Khan led a militia against the Taliban. He spoke to The World days before Afghans lost the fight". The World. Cambridge, MA: Public Radio Exchange.

- ^ a b "The Taleban leadership converges on Kabul as remnants of the republic reposition themselves". Afghanistan Analysts Network - English. 19 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d Ismail Khan, Herat, and Iranian Influence by Thomas H. Johnson, Strategic Insights, Volume III, Issue 7 (July 2004)[1] Archived 2013-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Coll, Steve. Ghost Wars. pg 40. 2004, Penguin Books.

- ^ Johnson, C. & Leslie, J. "Afghanistan: The Mirage of Peace", New York: Zed Books, 2008. p47-69, 180.

- ^ Johnson, C. & Leslie, J. "Afghanistan: The Mirage of Peace", New York: Zed Books, 2008. p180.

- ^ Johnson, C. & Leslie, J. "Afghanistan: The Mirage of Peace", New York: Zed Books, 2008. p69.

- ^ Giustozzi, A. "Empires of Mud: Wars and Warlords in Afghanistan", London: Hurst & Co., 2009. p259.

- ^ GRAHAM BOWLEY (12 November 2012). "Afghan Warlord's Call to Arms Rattles Officials". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ MPs launch signature campaign to summon Khan Archived 2015-05-31 at the Wayback Machine, Pajhwok Afghan News. November 15, 2012.

- ^ "Rocket attack over border kills 4 Afghan children - Yahoo! News". Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ Murphy, Brett (18 June 2006). "Guantanamo Bay detainees not given access to witnesses despite availability". Jurist. Archived from the original on 20 June 2006.

- ^ a b Carlotta Gall, Andy Worthington (5 February 2008). "Time Runs Out for an Afghan Held by the U.S." The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 May 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

Abdul Razzaq Hekmati was regarded here as a war hero, famous for his resistance to the Russian occupation in the 1980s and later for a daring prison break he organized for three opponents of the Taliban government in 1999.

- ^ "Ismail Khan mobilises hundreds in Herat to fight Taliban". www.thenews.com.pk. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ a b Varshalomidze, Tamila; Siddiqui, Usaid. "Taliban claims to have taken Kandahar as onslaught continues". Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Taliban detain veteran militia chief Khan in Afghanistan's Herat - official". 13 August 2021. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ a b c Trofimov, Yaroslav (13 August 2021). "Taliban Seize Kandahar, Prepare to March on Afghan Capital Kabul". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Tariq Ghazniwal [@TGhazniwal] (13 August 2021). "Short Interview of Warlord #Ismail_Khan after his capturing in #Herat" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Taliban captures Afghan commander Ismail Khan after fall of Herat". 13 August 2021. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ Jaafari, Shirin (16 August 2021). "Former warlord Ismail Khan led a militia against the Taliban. He spoke to The World days before Afghans lost the fight". The World. Cambridge, MA: Public Radio Exchange.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Radio Free Afghanistan journalist attacked and expelled from Herat" (Press release). Reporters Without Borders. Archived from the original on 6 October 2013.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Torture and Political Repression in Herat, John Sifton (November 5, 2002)". Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ "Profile: Ismail Khan, BBC News (September 2004)". Archived from the original on 10 June 2004. Retrieved 13 September 2004.