Hypophosphatemia

| Hypophosphatemia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Low blood phosphate, phosphate deficiency, hypophosphataemia |

| |

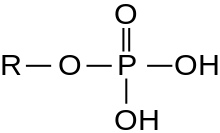

| Phosphate group chemical structure | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Weakness, trouble breathing, loss of appetite[1] |

| Complications | Seizures, coma, rhabdomyolysis, softening of the bones[1] |

| Causes | Alcohol use disorder, refeeding in those with malnutrition, hyperventilation, diabetic ketoacidosis, burns, certain medications[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood phosphate < 0.81 mmol/L (2.5 mg/dL)[1] |

| Treatment | Based on the underlying cause, phosphate[1][2] |

| Frequency | 2% (people in hospital)[1] |

Hypophosphatemia is an electrolyte disorder in which there is a low level of phosphate in the blood.[1] Symptoms may include weakness, trouble breathing, and loss of appetite.[1] Complications may include seizures, coma, rhabdomyolysis, or softening of the bones.[1]

Causes include alcohol use disorder, refeeding in those with malnutrition, recovery from diabetic ketoacidosis, burns, hyperventilation, and certain medications.[1] It may also occur in the setting of hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, and Cushing syndrome.[1] It is diagnosed based on a blood phosphate concentration of less than 0.81 mmol/L (2.5 mg/dL).[1] When levels are below 0.32 mmol/L (1.0 mg/dL) it is deemed to be severe.[2]

Treatment depends on the underlying cause.[1] Phosphate may be given by mouth or by injection into a vein.[1] Hypophosphatemia occurs in about 2% of people within hospital and 70% of people in the intensive care unit (ICU).[1][3]

Signs and symptoms

- Muscle dysfunction and weakness – This occurs in major muscles, but also may manifest as: diplopia, low cardiac output, dysphagia, and respiratory depression due to respiratory muscle weakness.

- Mental status changes – This may range from irritability to gross confusion, delirium, and coma.

- White blood cell dysfunction, causing worsening of infections.

- Instability of cell membranes due to low adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels – This may cause rhabdomyolysis with increased serum levels of creatine phosphokinase, and also hemolytic anemia.

- Increased affinity for oxygen in the blood caused by decreased production of 2,3-bisphosphoglyceric acid.

- If hypophosphatemia is chronic; rickets in children or osteomalacia in adults may develop.

Causes

- Refeeding syndrome – This causes a demand for phosphate in cells due to the action of hexokinase, an enzyme that attaches phosphate to glucose to begin metabolism of glucose. Also, production of ATP when cells are fed and recharge their energy supplies requires phosphate. A similar mechanism is seen in the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis,[4] which can be complicated by respiratory failure in these cases due to respiratory muscle weakness.[5][6]

- Respiratory alkalosis – Any alkalemic condition moves phosphate out of the blood into cells. This includes most common respiratory alkalemia (a higher than normal blood pH from low carbon dioxide levels in the blood), which in turn is caused by any hyperventilation (such as may result from sepsis, fever, pain, anxiety, drug withdrawal, and many other causes). This phenomenon is seen because in respiratory alkalosis carbon dioxide (CO2) decreases in the extracellular space, causing intracellular CO2 to freely diffuse out of the cell. This drop in intracellular CO2 causes a rise in cellular pH which has a stimulating effect on glycolysis. Since the process of glycolysis requires phosphate (the end product is adenosine triphosphate), the result is a massive uptake of phosphate into metabolically active tissue (such as muscle) from the serum. However, that this effect is not seen in metabolic alkalosis, for in such cases the cause of the alkalosis is increased bicarbonate rather than decreased CO2. Bicarbonate, unlike CO2, has poor diffusion across the cellular membrane and therefore there is little change in intracellular pH.[7]

- Alcohol use disorder – Alcohol impairs phosphate absorption. People who excessively consume alcohol are usually also malnourished with regard to minerals. In addition, alcohol treatment is associated with refeeding, which further depletes phosphate, and the stress of alcohol withdrawal may create respiratory alkalosis, which exacerbates hypophosphatemia (see above).

- Malabsorption – This includes gastrointestinal damage, and also failure to absorb phosphate due to lack of vitamin D, or chronic use of phosphate binders such as sucralfate, aluminum-containing antacids, and (more rarely) calcium-containing antacids.

- Intravenous iron (usually for anemia) may cause hypophosphatemia. The loss of phosphate is predominantly the result of renal wasting.

Primary hypophosphatemia is the most common cause of non-nutritional rickets. Laboratory findings include low-normal serum calcium, moderately low serum phosphate, elevated serum alkaline phosphatase, and low serum 1,25 dihydroxy-vitamin D levels, hyperphosphaturia, and no evidence of hyperparathyroidism.[8]

Hypophosphatemia decreases 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG) causing a left shift in the oxyhemoglobin curve.[citation needed]

Other rarer causes include:

- Certain blood cancers such as lymphoma or leukemia

- Hereditary causes

- Liver failure

- Tumor-induced osteomalacia[citation needed]

Pathophysiology

Hypophosphatemia is caused by the following three mechanisms:

- Inadequate intake (often unmasked in refeeding after long-term low phosphate intake)

- Increased excretion (e.g. in hyperparathyroidism, hypophosphatemic rickets)

- Shift of phosphorus from the extracellular to the intracellular space.[clarification needed] This can be seen in treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis, refeeding, short-term increases in cellular demand (e.g. hungry bone syndrome) and acute respiratory alkalosis.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

Hypophosphatemia is diagnosed by measuring the concentration of phosphate in the blood. Concentrations of phosphate less than 0.81 mmol/L (2.5 mg/dL) are considered diagnostic of hypophosphatemia, though additional tests may be needed to identify the underlying cause of the disorder.[9]

Treatment

Standard intravenous preparations of potassium phosphate are available and are routinely used in malnourished people and people who consume excessive amounts of alcohol. Supplementation by mouth is also useful where no intravenous treatment are available. Historically one of the first demonstrations of this was in people in concentration camp who died soon after being re-fed: it was observed that those given milk (high in phosphate) had a higher survival rate than those who did not get milk.[citation needed]

Monitoring parameters during correction with IV phosphate[10]

- Phosphorus levels should be monitored after 2 to 4 hours after each dose, also monitor serum potassium, calcium and magnesium. Cardiac monitoring is also advised.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Hypophosphatemia". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ a b Adams, James G. (2012). Emergency Medicine: Clinical Essentials (Expert Consult - Online and Print). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1416. ISBN 978-1455733941.

- ^ Yunen, Jose R. (2012). The 5-Minute ICU Consult. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 152. ISBN 9781451180534.

- ^ Pappoe, Lamioko Shika; Singh, Ajay K. (2010). "Hypophosphatemia". Decision Making in Medicine: 392–393. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-04107-2.50138-1. ISBN 978-0-323-04107-2.

- ^ Konstantinov, NK; Rohrscheib, M; Agaba, EI; Dorin, RI; Murata, GH; Tzamaloukas, AH (25 July 2015). "Respiratory failure in diabetic ketoacidosis". World Journal of Diabetes. 6 (8): 1009–1023. doi:10.4239/wjd.v6.i8.1009. PMC 4515441. PMID 26240698.

- ^ Choi, HS; Kwon, A; Chae, HW; Suh, J; Kim, DH; Kim, HS (June 2018). "Respiratory failure in a diabetic ketoacidosis patient with severe hypophosphatemia". Annals of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism. 23 (2): 103–106. doi:10.6065/apem.2018.23.2.103. PMC 6057019. PMID 29969883.

- ^ O'Brien, Thomas M; Coberly, LeAnn (2003). "Severe Hypophosphatemia in Respiratory Alkalosis" (PDF). Advanced Studies in Medicine. 3 (6): 347. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-08-15. Retrieved 2011-06-17.

- ^ Toy, Girardet, Hormann, Lahoti, McNeese, Sanders, and Yetman. Case Files: Pediatrics, Second Edition. 2007. McGraw Hill.

- ^ "Hypophosphatemia - Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders - Merck Manuals Professional Edition". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ^ Shajahan, A.; Ajith Kumar, J.; Gireesh Kumar, K. P.; Sreekrishnan, T. P.; Jismy, K. (2015). "Managing hypophosphatemia in critically ill patients: A report on an under-diagnosed electrolyte anomaly". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 40 (3): 353–354. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12264. PMID 25828888. S2CID 26635746.