Hubert Robert

Hubert Robert | |

|---|---|

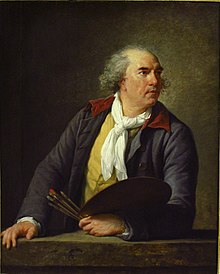

Hubert Robert by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun | |

| Born | 22 May 1733 Paris, France |

| Died | 15 April 1808 (aged 74) Paris, France |

Hubert Robert (French pronunciation: [ybɛʁ ʁɔbɛʁ]; 22 May 1733 – 15 April 1808) was a French painter in the school of Romanticism, noted especially for his landscape paintings and capricci, or semi-fictitious picturesque depictions of ruins in Italy and of France.[1]

Biography

Early years

Hubert Robert was born in Paris in 1733. His father, Nicolas Robert, was in the service of François-Joseph de Choiseul, marquis de Stainville a leading diplomat from Lorraine. Young Robert finished his studies with the Jesuits at the Collège de Navarre in 1751 and entered the atelier of the sculptor Michel-Ange Slodtz who taught him design and perspective but encouraged him to turn to painting. In 1754 he left for Rome in the train of Étienne-François de Choiseul, son of his father's employer, who had been named French ambassador and would become a Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs to Louis XV in 1758.

In Rome

He spent fully eleven years in Rome, a remarkable length of time; after the young artist's official residence at the French Academy in Rome ran out, he supported himself by works he produced for visiting connoisseurs like the abbé de Saint-Non, who took Robert to Naples in April 1760 to visit the ruins of Pompeii. The marquis de Marigny, director of the Bâtiments du Roi kept abreast of his development in correspondence with Natoire, director of the French Academy, who urged the pensionnaires to sketch out-of-doors, from nature: Robert needed no urging; drawings from his sketchbooks document his travels: Villa d'Este, Caprarola.

The contrast between the ruins of ancient Rome and the life of his time excited his keenest interest.[2] He worked for a time in the studio of Giovanni Paolo Panini, whose influence can be seen in the Vue imaginaire de la galerie du Louvre en ruine (illustration). Robert spent his time in the company of young artists in the circle of Piranesi, whose capricci of romantically overgrown ruins influenced him so greatly that he gained the nickname Robert des ruines.[3] The albums of sketches and drawings he assembled in Rome supplied him with motifs that he worked into paintings throughout his career.[4]

He is reported to have carved his name into the walls of the Colosseum in 1767.[5]

In Paris

His success on his return to Paris in 1765 was rapid: the following year he was received by the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, with a Roman capriccio, The Port of Rome, ornamented with different Monuments of Architecture, Ancient and Modern.[6] Robert's first exhibition at the Salon of 1767, consisting of thirteen paintings and a number of drawings, prompted Denis Diderot to write: "The ideas which the ruins awake in me are grand." Robert subsequently showed work at every Salon until 1802.[7] He was successively appointed "Designer of the King's Gardens", "Keeper of the King's Pictures" and "Keeper of the Museum and Councilor to the Academy".[8]

Robert was arrested in October 1793, during the French Revolution.[9] During the ten months of his detention at Sainte-Pélagie and Saint-Lazare he made many drawings, painted at least 53 canvases, and painted numerous vignettes of prison life on plates.[7] He was freed one week after the fall of Robespierre.[10] Robert narrowly escaped the guillotine when through error another prisoner with a similar name was guillotined in his place.[11]

Subsequently, he was placed on the committee of five in charge of the new national museum at the Palais du Louvre.

The Revolution also resulted in the destruction of some of Robert's work; his painting Péché Cardinal (ca.1799) is one that is thought to be lost or destroyed in a fire.[citation needed] Robert had designed the decorations for a little theatre in the new wing at the location of the current staircase Gabriel in the Palace of Versailles. Designed to seat about 500, this theatre was built from the summer of 1785 and opened in early 1786. It was intended to serve as an ordinary court theatre, replacing the Theatre of the Princes Court which was too old and too small, but was destroyed during the time of Louis Philippe. A watercolour of Robert's design is in the National Archives in Paris.[12]

Robert died of a stroke on 15 April 1808.

Style and legacy

The quantity of his work is immense, comprising perhaps one thousand paintings and ten thousand drawings.[7] The Louvre alone contains nine paintings by his hand and specimens are frequently to be met with in provincial museums and private collections. Robert's work has more or less of that scenic character which justified his selection by Voltaire to paint the decorations of his theatre at Ferney.[2]

His work was much engraved by the abbé de Saint-Non, with whom he had visited Naples in the company of Fragonard during his early days; in Italy his work has also been frequently reproduced by Chatelain, Linard, Le Veau, and others.[2]

He is noted for the liveliness and point with which he treated the subjects he painted. Equally at ease painting small easel pictures or huge decorations, he worked quickly using an alla prima technique.[13] Along with this incessant activity as an artist, his daring character and many adventures attracted general admiration and sympathy. In the fourth canto of his L'Imagination Jacques Delille celebrated Robert's miraculous escape when lost in the catacombs.[2]

Robert and picturesque gardens

Enterprising and prolific, Robert also acted in a role similar to that of a modern-day art director, conceptualizing fashionably dilapidated gardens for several aristocratic clients, summarized by his possible intervention at Ermenonville; there he would have been working with the architect Jean-Marie Morel for the marquis de Girardin, who was the author of Compositions des paysages (1777) and had distinct views of his own. In 1786 he began his better documented[14] collaboration at Méréville, with his most significant patron, the financier Jean-Joseph de Laborde, who found François-Joseph Bélanger's plans too expensive and perhaps too formal.

Though documents are again lacking, Hubert Robert's name is invariably invoked in connection with Marie Antoinette's 'premier architecte' Richard Mique through several phases of the creation of an informal landscape garden at the Petit Trianon, and the setting of the petit hameau. Robert's contribution to garden design was not in making practical ground plans for improvements but in providing atmospheric inspiration for the proposed effect.[15] At Ermenonville and at Méréville "Hubert Robert's paintings both recorded and inspired", according to W.H. Adams:[16] Robert's four large ruin fantasies, painted in 1787 for Méréville[17] may be searched in vain for direct connections with the garden. Hubert's paintings of the Moulin Joly of his friend Claude-Henri Watelet render the fully-grown atmosphere of a garden that had been under way since 1754. His set of six Italianate landscape panels painted for Bagatelle[18] were not the inspiration for the formal turfed parterre set in the thinned woodlands, designed by Bélanger; the later picturesque extensions of Bagatelle were carried out by its Scottish gardener, William Blaikie.[19] Robert's commissioned painting of the long-delayed rejuvenation of the park at Versailles, begun in 1774 with the cutting down of the trees for sale as firewood, is a record of the event, resonant with allegorical meaning.[20] Robert was more certainly responsible for the conception of the grotto and cascades of the 'Baths of Apollo,' tucked within a grove of the chateau's park and built to house François Girardon's celebrated sculpture group Apollo Attended by Nymphs.

Gallery

Works on paper

-

Capriccio (ca. 1756), watercolor, 56.4 x 41.3 cm., Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Oval Fountain in the Villa d'Este Gardens, Tivoli (1760), 32.7 x 45 cm., National Gallery of Art

-

The Large Staircase (ca. 1761–65), 45 x 32.3 cm., Pen and ink, wash, watercolor, and chalk, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

-

Young Artists in the Studio (ca.1763-65), re chalk, 35.2 x 41.2 cm., Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Arch of Titus in Rome (1760s), watercolor, 35 x 49.5 cm., Czartoryski Museum

-

Artist Sketching a Young Girl (ca. 1773), red chalk, 25.5 x 33.8 cm., Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Women in Landscape (ca. 1773), ink, wash, & chalk, 36.6 x 28.7 cm., Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Boat Journey (1774), sanguine, 28.9 x 36.5 cm., National Museum in Warsaw

-

Draughtsman of the Borghese Vase (ca. 1775), chalk, 36.5 x 29 cm., Museu de Belles Arts de València

-

Figures in a Colonnade (ca. 1780), ink, wash, & chalk, 58.6 x 44 .7 cm., Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Self Portrait in Prison (ca 1793–94), ink, wash, watercolor and chalk, 17.6 x 23.8 cm., Galerie Coatalem

Oil paintings

-

The Old Bridge (1760), 76.2 x 100.3 cm., Yale University Art Gallery

-

Italian Kitchen (ca. 1760–67), 60 x 75 cm., National Museum in Warsaw

-

Orator in Prison (1760s), 48 x 38 cm., Nationalmuseum

-

The Pantheon with the Port of Ripetta (1766), 119 x 145 cm., Beaux-Arts de Paris

-

The Fire of Rome (ca. 1771), 75.5 x 93 cm., Musée d'art moderne André Malraux

-

École de Chirurgie Under Construction (1773), 76 x 91.5 cm., Musée Carnavalet

-

The Finding of the Laocoon (1773), 119.3 x 162.5 cm., Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

-

The Tivoli Waterfalls (1776), 50 x 74 cm., Petit Palais

-

Studio of an Antiquities Restorer in Rome (1783), 101 x 143 cm., Toledo Museum of Art

-

Flight of Galatea (mid 1780s), 50 x: 42 cm., Hermitage Museum

-

Shipwreck (1780s), 322 x 199 cm., Worcester Art Museum

-

The Fire of the Paris Opera (1781), 123.5 × 171 cm., private collection

-

The Landing Place (1787–88), 255 x 223 cm., Art Institute of Chicago

-

The Fountains (1787–88), 255 x 221 cm., Art Institute of Chicago

-

The Old Temple (1787–88), 255 x 223 cm., Art Institute of Chicago

-

The Obelisk (1787–88), 255 x 223 cm., Art Institute of Chicago

-

The Bastille in the Early Days of Its Demolition (1789), 96 x 135 cm., Musée Carnavalet

-

Neglected Statue (1790s), 40 x 31 cm., Hermitage Museum

-

Girls Dancing Around an Obelisk (1798), 120 x 99 cm., Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

-

Project for the Transformation of the Grande Galerie du Louvre (1796), 115 x 145 cm., Louvre

-

Imaginary View of the Grand Gallery of the Louvre in Ruins (1796), 114.5 x 146 cm., Louvre

-

Roman Capriccio (1798 ), 94 x 117 cm., Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe

-

Architectural Fantasy (ca. 1802–08),114 x 147.8 cm., Rhode Island School of Design Museum

References, notes and sources

- References and notes

- ^ Jean de Cayeux. "Robert, Hubert." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 13 Jan. 2017

- ^ a b c d Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Robert possessed no fewer than twenty-five of Pannini's canvases. (Jean Cailleux, "Introduction to the Method of Hubert Robert"The Burlington Magazine 109 No. 767, February 1967), p. i.

- ^ Sarah Catala, "La matérialité fonctionnelle, Quelques refléxions sur les pratiques de dessin d'Hubert Robert", in exh. cat. Hubert Robert, un peintre visionnaire, Paris, éditions du musée du Louvre / Somogy, p. 65-72.

- ^ Salcedo, Andrea (9 July 2023). "A not-so-brief history of the Colosseum for confused vandals". Washington Post.

- ^ Le port de Rome, orné de différens Monumens d'Architecture ancien et moderne.

- ^ a b c Colin B. Bailey, "Hubert Robert & the Joy of Ruins", The New York Review of Books 63.15 (October 13, 2016), pp. 35–37.

- ^ Dessinateur des Jardins du Roi, Garde des tableaux du Roi, and Garde du Museum et conseiller à l'Academie

- ^ 18 brumaire An II

- ^ He was released 18 thermidor 1794.

- ^ Histoire de Paris, Héron de Villefosse, Editions Grasset (Paris), 1955, pg 181

- ^ A colour print of a detail of the design is mounted in Huisman, p88.

- ^ Hubert Robert Biography, National Gallery of Art https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.1832.html

- ^ Victor Carlson, "Hubert Robert in Rome: Some Pen-and-Wash Drawings" Master Drawings 39.3 (Autumn 2001, pp. 288-299) p. 291.

- ^ Compare the role of Louis Moreau at Bagatelle.

- ^ Adams1979:104

- ^ At the Art Institute of Chicago.

- ^ At the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Joseph Baillio, "Hubert Robert's Decorations for the Château de Bagatelle" Metropolitan Museum Journal 27 (1992), pp. 149–182.

- ^ Paula Rea Radisich, "The King Prunes His Garden: Hubert Robert's Picture of the Versailles Gardens in 1775" Eighteenth-Century Studies 21.4 (Summer 1988), pp. 454–471.

- Sources

- Adams, William Howard, The French Garden 1500–1800 (New York: Braziller) 1979.

- Huisman, Philippe, French Watercolours of the 18th Century (1969) London, Thames and Hudson ISBN 978-0-500-23105-0

- Wiebenson, Dora, The Picturesque Garden in France (Princeton University Press) 1978.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Robert, Hubert". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 402.

- Sarah Catala. Les Hubert Robert de Besançon. Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2013 [catalogue raisonné of drawings from public library and fine art museum of Besançon].

External links

- Joconde - Catalogue des Collections des Musées de France www.culture.gouv.fr (Ministère de la culture et de la communication) — List of the work of Robert (315 entries), French.