History of medicine in the United States

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

The history of medicine in the United States encompasses a variety of approaches to health care in the United States spanning from colonial days to the present. These interpretations of medicine vary from early folk remedies that fell under various different medical systems to the increasingly standardized and professional managed care of modern biomedicine.

Colonial Era

At the time settlers first came to the United States, the predominant medical system was humoral theory, or the idea that diseases are caused by an imbalance of bodily fluids.[1] Settlers initially believed that they should only use medicines that fit in this medical system and were made out of "such things only as grown in England, they being most fit for English Bodies," as said in The English Physitian Enlarged, a medical handbook commonly owned by early settlers.[2] However, as settlers were faced with new diseases and a scarcity of typical plants and herbs used to make therapies in England, they increasingly turned to local flora and Native American remedies as alternatives to European medicine. The Native American medical system typically tied the administration of herbal treatments with rituals and prayers.[3] This inclusion of a different spiritual system was denounced by Europeans, in particular Spanish colonies, as part of the religious fervor associated with the Inquisition. Any Native American medical information that did not agree with humoral theory was deemed heretical by Spanish authorities, and tribal healers were condemned as witches.[4] In English colonies on the other hand, it was more common for settlers to seek medical help from Native American healers. [3]

Disease environment

Mortality was very high for new arrivals, and high for children in the colonial era.[5][6] Malaria was deadly to many new arrivals. The disease environment was very hostile to European settlers, especially in all the Southern colonies. Malaria was endemic in the South, with very high mortality rates for new arrivals. Children born in the new world had some immunity—they experienced mild recurrent forms of malaria but survived. For an example of newly arrived able-bodied young men, over one-fourth of the Anglican missionaries died within five years of their arrival in the Carolinas.[7] Mortality was high for infants and small children, especially from diphtheria, yellow fever, and malaria. Most sick people turn to local healers, and used folk remedies. Others relied upon the minister-physicians, barber-surgeons, apothecaries, midwives, and ministers; a few used colonial physicians trained either in Britain, or an apprenticeship in the colonies. There was little government control, regulation of medical care, or attention to public health. By the 18th century, Colonial physicians, following the models in England and Scotland, introduced modern medicine to the cities. This allowed some advances in vaccination, pathology, anatomy and pharmacology.[8]

There was a fundamental difference in the human infectious diseases present in the indigenous peoples and that of sailors and explorers from Europe and Africa. Some viruses, like smallpox, have only human hosts and appeared to have never occurred on the North American continent before 1492. The indigenous people lacked genetic resistance to such new infections, and suffered overwhelming mortality when exposed to smallpox, measles, malaria, tuberculosis and other diseases. The depopulation occurred years before the European settlers arrived in the vicinity and resulted from contact with trappers.[9][10]

Medical organization

The French colonial city of New Orleans, Louisiana opened two hospitals in the early 1700s. The first was the Royal Hospital, which opened in 1722 as a small military infirmary, but grew to importance when the Ursuline Sisters took over its management in 1727 and made it a major hospital for the public, with a new and larger building built in 1734. The other was the Charity Hospital, which was staffed by many of the same people but was established in 1736 as a supplement to the Royal Hospital so that the poorer classes (who usually could not afford treatment at the Royal Hospital) had somewhere to go.[11]

In the British colonies, medicine was rudimentary for the first few generations, as few upper-class British physicians emigrated to the colonies. The first medical society was organized in Boston in 1735. In the 18th century, 117 Americans from wealthy families had graduated in medicine in Edinburgh, Scotland, but most physicians learned as apprentices in the colonies.[12] In Philadelphia, the Medical College of Philadelphia was founded in 1765, and became affiliated with the university in 1791. In New York, the medical department of King's College was established in 1767, and in 1770, awarded the first American M.D. degree.[13]

Smallpox inoculation was introduced 1716–1766, well before it was accepted in Europe. The first medical schools were established in Philadelphia in 1765 and New York in 1768. The first textbook appeared in 1775, though physicians had easy access to British textbooks. The first pharmacopoeia appeared in 1778.[14][15] The European populations had a historic exposure and partial immunity to smallpox, but the Native American populations did not, and their death rates were high enough for one epidemic to virtually destroy a small tribe.[16]

Physicians in port cities realized the need to quarantine sick sailors and passengers as soon as they arrived. Pest houses for them were established in Boston (1717), Philadelphia (1742) Charleston (1752) and New York (1757). The first general hospital was established in Philadelphia in 1752.[17][18]

19th Century

Thomsonianism and eclectic medicine

In the 19th century the nation was flooded with medical sects promoting a wide range of alternative treatments for all ailments. The medical societies tried to impose licensing requirements in state law, but the eclectics undid their efforts. The most famous of the eclectics was Samuel Thomson (1769-1843), a self educated New England farm boy who developed a wildly popular herbal medical system.[19] He founded the Friendly Botanic Societies in 1813 and wrote a manual detailing his new methods.[20] He promised that even the worst ailments could be cured without any harsh treatments. There would be no surgery, no deliberate bleeding, no powerful drugs. Disease was a matter of maladjustment in the body's internal heat, and could be cured by applying certain herbs and medicinal plants, coupled with vomiting, enemas, and steam baths. Thomson's approach resonated with workers and farmers who distrusted the bloody hands of traditional physicians.[21] President Andrew Jackson endorsed the new fad, and Brigham Young promoted it to the new Mormon movement.[22]

Thomson was a master promoter. He patented his system and sold licenses to hundreds of field agents who gained patients during the cholera outbreaks of 1832 and 1834. By 1839, the movement claimed three million followers and was strongest in New England.[23]

However, in the 1840s it all fell apart. Thomson died in 1843, many patients grew worse after the treatment, while a bitter schism emerged among the Thomsonian agents. The result the sect's sharp decline by 1860. Nevertheless, Thomson's influence still can be seen among people suspicious of modern medicine. Many herbs he popularized, such as cayenne pepper, lobelia, and goldenseal, remain widely used to this day in herbal healing routines. The Thomsonians had been briefly successful in blocking state laws limited medical practice to licensed physicians. After the collapse the MDs made a comeback and reimposed strict licensing laws on the practice of medicine. [24]

Civil War

In the American Civil War (1861–65), as was typical of the 19th century, far more soldiers died of disease than in battle, and even larger numbers were temporarily incapacitated by wounds, disease and accidents.[25] Conditions were worse in the Confederacy, where doctors and medical supplies were in short supply.[26] The war had a dramatic long-term impact on American medicine, from new surgical technique to creation of many hospitals, to expanded nursing and to modern research facilities.

Death and survival in the rival armies

In the Civil War, as was typical of the 19th century, far more soldiers died of disease than in battle, and even larger numbers were temporarily incapacitated by wounds, disease and accidents.[27] Conditions were very poor in the Confederacy, where doctors, hospitals and medical supplies were in short supply.[28][29][30]

Medicine in the 1860s did not know about germs and it tolerated bad hygiene. The risk was highest at the beginning of the war when men who had seldom been far from home were brought together for training alongside thousands of strangers who carried unfamiliar germs. Men from rural areas were twice as likely to die from infectious diseases as soldiers from urban areas.[31] Recruits first encountered epidemics of the childhood diseases of chicken pox, mumps, whooping cough, and, especially, measles. Later the fatal disease environment included diarrhea, dysentery, typhoid fever, and malaria. Disease vectors were often unknown. Bullet wounds often led to gangrene, usually necessitating an amputation before it became fatal. The surgeons used chloroform if available, whiskey otherwise.[32] Harsh weather, bad water, inadequate shelter in winter quarters, poor sanitation within the camps, and dirty camp hospitals took their toll.[33] This was a common scenario in wars from time immemorial, and conditions faced by the Confederate army were even worse since the Union blockade sharply reduced medical supplies; adequate food, shoes and warm clothing were in very short supply.

Army hospitals

The Union had money and responded by building 204 army hospitals with 137,000 beds, with doctors, nurses and staff as needed, as well as hospital ships and trains located close to the battlefields. Mortality was only 8 percent.[34] What was critical in the Union was the emergence of skilled, well-funded medical organizers who took proactive action, especially in the much enlarged United States Army Medical Department,[35] and the United States Sanitary Commission, a new private agency.[36] Numerous other new agencies also targeted the medical and morale needs of soldiers, including the United States Christian Commission as well as smaller private agencies such as the Women's Central Association of Relief for Sick and Wounded in the Army (WCAR) founded in 1861 by Henry Whitney Bellows, and Dorothea Dix. Systematic funding appeals raised public consciousness, as well as millions of dollars. Many thousands of volunteers worked in the hospitals and rest homes, most famously poet Walt Whitman. Frederick Law Olmsted, a famous landscape architect, was the highly efficient executive director of the Sanitary Commission.[37]

States could use their own tax money to support their troops as Ohio did. Following the unexpected carnage at the battle of Shiloh in April 1862, the Ohio state government sent 3 steamboats to the scene as floating hospitals with doctors, nurses and medical supplies. The state fleet expanded to eleven hospital ships. The state also set up 12 local offices in main transportation nodes to help Ohio soldiers moving back and forth.[38] The U.S. Army learned many lessons and in 1886, it established the Hospital Corps. The Sanitary Commission collected enormous amounts of statistical data, and opened up the problems of storing information for fast access and mechanically searching for data patterns. The pioneer was John Shaw Billings (1838-1913). A senior surgeon in the war, Billings built the Library of the Surgeon General's Office (now the National Library of Medicine, the centerpiece of modern medical information systems. Billings figured out how to mechanically analyze medical and demographic data by turning information into numbers and punching onto cardboard cards as developed by his assistant Herman Hollerith. This was the origin of the computer punch card system that dominated computers and statistical data manipulation until the 1970s.[39]

Modern Medicine

After 1870 the Nightingale model of professional training of nurses was widely copied. Linda Richards (1841 – 1930) studied in London and became the first professionally trained American nurse. She established nursing training programs in the United States and Japan, and created the first system for keeping individual medical records for hospitalized patients.[40]

After the American Revolution, the United States was slow to adopt advances in European medicine, but adopted germ theory and science-based practices in the late 1800s as the medical education system changed.[41] Historian Elaine G. Breslaw describes earlier post-colonial American medical schools as "diploma mills", and credits the large 1889 endowment of Johns Hopkins Hospital for giving it the ability to lead the transition to science-based medicine.[42] Johns Hopkins originated several modern organizational practices, including residency and rounds. In 1910, the Flexner Report was published, standardizing many aspects of medical education. The Flexner Report is a book-length study of medical education and called for stricter standards for medical education based on the scientific approach used at universities, including Johns Hopkins.[43]

World War II

Nursing

As Campbell (1984) shows, the nursing profession was transformed by World War II. Army and Navy nursing was highly attractive and a larger proportion of nurses volunteered for service higher than any other occupation in American society.[44][45]

The public image of the nurses was highly favorable during the war, as exemplified by such Hollywood films as Cry "Havoc", which made the selfless nurses heroes under enemy fire. Some nurses were captured by the Japanese,[46] but in practice they were kept out of harm's way, with the great majority stationed on the home front. The medical services were large operations, with over 600,000 soldiers, and ten enlisted men for every nurse. Nearly all the doctors were men, with women doctors allowed only to examine patients from the Women's Army Corps.[44]

Women in Medicine

In the colonial era, women played a major role in terms of healthcare, especially regarding midwives and childbirth. Local healers used herbal and folk remedies to treat friends and neighbors. Published housekeeping guides included instructions in medical care and the preparation of common remedies. Nursing was considered a female role.[47] Babies were delivered at home without the services of a physician well into the 20th century, making the midwife a central figure in healthcare.[48][49]

The professionalization of medicine, starting slowly in the early 19th century, included systematic efforts to minimize the role of untrained uncertified women and keep them out of new institutions such as hospitals and medical schools.[50]

Doctors

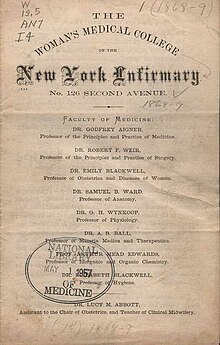

In 1849 Elizabeth Blackwell (1821–1910), an immigrant from England, graduated from Geneva Medical College in New York at the head of her class and thus became the first female doctor in America. In 1857, she and her sister Emily, and their colleague Marie Zakrzewska, founded the New York Infirmary for Women and Children, the first American hospital run by women and the first dedicated to serving women and children.[51] Blackwell viewed medicine as a means for social and moral reform, while a younger pioneer Mary Putnam Jacobi (1842-1906) focused on curing disease. At a deeper level of disagreement, Blackwell felt that women would succeed in medicine because of their humane female values, but Jacobi believed that women should participate as the equals of men in all medical specialties.[52] In 1982, nephrologist Leah Lowenstein became the first woman dean of a co-education medical school upon her appointment at Jefferson Medical College.[53]

Nursing

Nursing became professionalized in the late 19th century, opening a new middle-class career for talented young women of all social backgrounds. The School of Nursing at Detroit's Harper Hospital, begun in 1884, was a national leader. Its graduates worked at the hospital and also in institutions, public health services, as private duty nurses, and volunteered for duty at military hospitals during the Spanish–American War and the two world wars.[54]

The major religious denominations were active in establishing hospitals in many cities. Several Catholic orders of nuns specialized in nursing roles. While most lay women got married and stopped, or became private duty nurses in the homes and private hospital rooms of the wealthy, the Catholic sisters had lifetime careers in the hospitals. This enabled hospitals like St. Vincent's Hospital in New York, where nurses from the Sisters of Charity began their work in 1849; patients of all backgrounds were welcome, but most came from the low-income Catholic population.[55]

See also

Notes

- ^ Jouanna, Jacques. 2012. "The Legacy of the Hippocratic Treatise The Nature of Man: The Theory of the Four Humours" in Greek Medicine from Hippocrates to Galen, edited by Philip van der Eijk, pp. 335-360. Boston: Brill.

- ^ Culpeper, Nicholas. 1666. The English Physitian Enlarged. London.

- ^ a b Robinson, Martha. 2005. New Worlds, New Medicines: Indian Remedies and English Medicine in Early America. Early American Studies (Spring): 94-110.

- ^ Kay, Margarita. 1987. "Lay Theory Of Healing In Northwestern New Spain" Social Science & Medicine 24(12): 1051-1060.

- ^ Rebecca Jo Tannenbaum, Health and Wellness in Colonial America (ABC-CLIO, 2012)

- ^ Henry R. Viets, "Some Features of the History of Medicine in Massachusetts during the Colonial Period, 1620-1770," Isis (1935), 23:389-405

- ^ Bradford J. Wood, "'A Constant Attendance on God's Alter': Death, Disease, and the Anglican Church in Colonial South Carolina, 1706-1750," South Carolina Historical Magazine (1999) 100#3 pp. 204-220 in JSTOR

- ^ Richard H. Shryock, "Eighteenth Century Medicine in America," Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society (Oct 1949) 59#2 pp 275-292. online

- ^ Alfred W. Crosby, "Virgin soil epidemics as a factor in the aboriginal depopulation in America." William and Mary Quarterly (1976): 289-299 online; in JSTOR

- ^ James D. Rice, "Beyond 'The Ecological Indian' and 'Virgin Soil Epidemics': New Perspectives on Native Americans and the Environment." History Compass (2014) 12#9 pp: 745-757.

- ^ John Salvaggio, New Orleans' Charity Hospital: A Story of Physicians, Politics, and Poverty (1992) pp. 7-11.

- ^ Genevieve Miller, "A Physician in 1776," Clio Medica, Oct 1976, Vol. 11 Issue 3, pp 135-146

- ^ Jacob Ernest Cooke, ed. Encyclopedia of the North American colonies (3 vol 1992) 1:214

- ^ Carl Bridenbaugh, Cities in the Wilderness: The First Century of Urban Life in America 1625-1742 (1938) pp 399-400

- ^ Ola Elizabeth Winslow, A destroying angel: the conquest of smallpox in colonial Boston (1974).

- ^ Paul Kelton, Cherokee Medicine, Colonial Germs: An Indigenous Nation's Fight Against Smallpox, 1518–1824 (University of Oklahoma Press, 2015)

- ^ Richard Morris Encyclopedia of American History (1976) p 806.

- ^ Carl Bridenbaugh, Cities in the Wilderness: The First Century of Urban Life in America 1625-1742 (1938) p 401

- ^ John S. Haller Jr., Medical Protestants : the Eclectics in American Medicine, 1825-1939 (1994) pp. 37-55 online. For a fully detailed history see John S. Haller Jr., The People's Doctor: Samuel Thomson and the American Botanical Movement 1790-1860 (2001).

- ^ Samuel Thomson, New guide to health, or, Botanic family physician: containing a complete system of practice, upon a plan entirely new; with a description of the vegetables made use of, and directions for preparing and administering them to cure disease; to which is prefixed A narrative of the life and medical discoveries of the author (1822 edition) online

- ^ James O. Breeden, "Thomsonianism in Virginia." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 82.2 (1974): 150-180 online.

- ^ Linda P. Wilcox, "The imperfect science: Brigham Young on medical doctors." Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 12.3 (1979): 26-36.

- ^ Daniel J. Wallace, "Thomsonians: The People's Doctors." Clio Medica 14 (1980): 169-86.

- ^ Toby A. Appel, "The Thomsonian movement, the regular profession, and the state in antebellum Connecticut: a case study of the repeal of early medical licensing laws." Journal of the history of medicine and allied sciences 65.2 (2010): 153-186.

- ^ George Worthington Adams, Doctors in Blue: The Medical History of the Union Army in the Civil War (1996); Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein, The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine (2012).

- ^ H.H. Cunningham, Doctors in Gray: The Confederate Medical Service (1993).

- ^ George Worthington Adams, Doctors in Blue: The Medical History of the Union Army in the Civil War (1996) online

- ^ H.H. Cunningham, Doctors in Gray: The Confederate Medical Service (1993) online

- ^ James I. Robertson, Soldiers Blue and Gray (1998) pp.145–170.

- ^ For the historiography see Michael A. Flannery, "Medicine and Health Care" in A Companion to the U.S. Civil War ed. by Aaron Sheehan-Dean (Wiley, 2014) pp.592-607 online.

- ^ J. David Hacker, "A Census-Based Count of the Civil War Dead," Civil War History 57#4 (2011), pp. 307-348 at p. 315. online

- ^ Gordon E. Dammann, and Alfred Jay Bollet, Images of Civil War Medicine: A Photographic History (2007) pp. 163–173.

- ^ Kenneth Link, "Potomac Fever: The Hazards of Camp Life," Vermont History, (1983) 51#2 pp 69-88 online

- ^ Adams, pp. 150–153.

- ^ Mary C. Gillett, The Army Medical Department, 1818-1865 (1987)

- ^ William Quentin Maxwell, Lincoln's Fifth Wheel: The Political History of the U.S. Sanitary Commission (1956)

- ^ Justin Martin, Genius of Place: The Life of Frederick Law Olmsted (2011) pp 178-230

- ^ Eugene E. Roseboom, The Civil War Era, 1850-1873 (1944) p 396

- ^ James H. Cassedy, "Numbering the North's Medical Events: Humanitarianism and Science in Civil War Statistics," Bulletin of the History of Medicine, (1992) 66#2 pp 210-233

- ^ Mary Ellen Doona, "Linda Richards and Nursing in Japan, 1885-1890," Nursing History Review (1996) Vol. 4, p99-128

- ^ Breslaw, Elaine G. (March 2014). Lotions, Potions, Pills, and Magic: Health Care in Early America. NYU Press. ISBN 978-1479807048.

- ^ "KERA Think: Health Care in Early America". 2012-10-29. Retrieved 2012-11-01.

- ^ Ludmerer, Kenneth M. (2005). Time to heal : American medical education from the turn of the century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-518136-0. OCLC 57282902.

- ^ a b D'Ann Campbell, Women at War with America: Private Lives in a Patriotic Era (1984) ch 2

- ^ Philip A. Kalisch and Beatrice J. Kalisch, American Nursing: A History (4th ed. 2003)

- ^ Elizabeth Norman, We Band of Angels: The Untold Story of American Nurses Trapped on Bataan by the Japanese (1999)

- ^ Rebecca Jo Tannenbaum, The Healer's Calling: Women and Medicine in Early New England (Cornell University Press, 2002).

- ^ Judy Barrett Litoff, "An historical overview of midwifery in the United States." Pre-and Peri-natal Psychology Journal 5.1 (1990): 5+ online Archived 2018-10-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Judy Barrett Litoff, "Midwives and History." In Rima D. Apple, ed., The History of Women, Health, and Medicine in America: An Encyclopedic Handbook (Garland Publishing, 1990) covers the historiography.

- ^ Regina Morantz-Sanchez, Sympathy and science: Women physicians in American medicine (2005). pp 1-27

- ^ "Changing the Face of Medicine | Dr. Emily Blackwell". Nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- ^ Regina Morantz, "Feminism, Professionalism and Germs: The Thought of Mary Putnam Jacobi and Elizabeth Blackwell," American Quarterly (1982) 34:461-478. in JSTOR

- ^ Angelo, Michael; Varrato, Matt (2011-10-01). "Leah Lowenstein, MD Nation's first female Dean of a co-ed medical school (1981)". 50 and Forward: Posters.

- ^ Kathleen Schmeling, "Missionaries of Health: Detroit's Harper Hospital School of Nursing, Michigan History (2002) 86#1 pp 28-38.

- ^ Bernadette McCauley, Who Shall Take Care of Our Sick?: Roman Catholic Sisters and the Development of Catholic Hospitals in New York City (2005) except and text search

Further reading

Surveys

- Beecher, Henry K., and Mark D. Altschule. Medicine at Harvard: The First 300 Years (1977)

- Burnham, John C. Health Care in America: A history (2015), A standard comprehensive scholarly history excerpt

- Byrd, W. Michael, and Linda A. Clayton. An American health dilemma: A medical history of African Americans and the problem of race: Beginnings to 1900 (Routledge, 2012).

- Deutsch, Albert. The mentally ill in America-A History of their care and treatment from colonial times (1937).

- Duffy, John. From Humors to Medical Science: A History of American Medicine (2nd ed. 1993)

- Duffy, John. The Sanitarians: A History of American Public Health (1990)

- Grob, Gerald M. The Deadly Truth: A History of Disease in America (2002) online

- Johnston, Robert D., ed. The politics of healing: histories of alternative medicine in twentieth-century North America (Routledge, 2004).

- Judd, Deborah, and Kathleen Sitzman. A history of American nursing (2nd ed. Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2013).

- Kalisch, Philip A., and Beatrice J. Kalisch. American Nursing: A History (4th ed. 2003)

- Leavitt, Judith Walzer, and Ronald L. Numbers, eds. Sickness and health in America: Readings in the history of medicine and public health (3rd ed. 1997). Essays by experts.

- Reverby, Susan, and David Rosner, eds. Health Care in America: Essays in Social History (1979).

- Risse, Guenter B., Ronald L. Numbers, and Judith Walzer Leavitt, eds. Medicine without doctors: Home health care in American history (Science History Publications/USA, 1977).

- Shryock, Richard H. "The American Physician in 1846 and in 1946: A Study in Professional Contrasts," Journal of the American Medical Association 134:417-424, 1947.

- Starr, Paul, The Social Transformation of American Medicine, Basic Books, 1982. ISBN 0-465-07934-2

- Stevens, Rosemary A., Charles E. Rosenberg, and Lawton R. Burns. History And Health Policy in the United States: Putting the Past Back in (2006) excerpt and text search

- Warner, John Harley Warner and Janet A. Tighe, eds. Major Problems in the History of American Medicine and Public Health (2001) 560pp; Primary and secondary sources

To 1910

- Abrams, Jeanne E. Revolutionary Medicine: The Founding Fathers and Mothers in Sickness and in Health. New York: New York University Press, 2013.

- Blake, John B. Public Health in the Town of Boston, 1630 – 1822 (1959)

- Bonner, Thomas Neville. Becoming a Physician: Medical Education in Great Britain, France, Germany, and the United States, 1750–1945 (1995)

- Breslaw, Elaine G. (2014). Lotions, Potions, Pills, and Magic: Health Care in Early America. NYU Press. ISBN 978-1479807048.

- Byrd, W. Michael and Linda A. Clayton. An American Health Dilemma, V.1: A Medical History of African Americans and the Problem of Race, Beginnings to 1900 - Vol. 1 (2000) online edition

- Dobson, Mary J. "Mortality Gradients and Disease Exchanges: Comparisons from Old England and Colonial America," Social History of Medicine 2 (1989): 259 – 297.

- Duffy, John. Epidemics in Colonial America (1953)

- Duffy, John. A History of Public Health in New York City, 1625 – 1866 (1968)

- Fett, Sharla M. Working Cures: Healing, Health, and Power on Southern Slave Plantations. (2002)

- Flexner, Simon, and James Thomas Flexner. William Henry Welch and the Heroic Age of American Medicine (1941), around 1900

- Grob, Gerald. The Deadly Truth: A History of Disease in America (2002) online edition

- Haller Jr.; John S. Medical Protestants: The Eclectics in American Medicine, 1825-1939 (1994) online edition

- Ludmerer, Kenneth M. Learning to Heal: The Development of American Medical Education (1985).

- Ludmerer, Kenneth M. "The Rise of the Teaching Hospital in America," Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 38:389-414, 1983.

- Nolosco, Marynita Anderson. Physician heal thyself: medical practitioners of eighteenth-century New York (Peter Lang, 2004)

- Packard, Francis R. A History of Medicine in the United States (1931)

- Parmet, Wendy E. "Health Care and the Constitution: Public Health and the Role of the State in the Framing Era," 20 Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly 267–335, 285-302 (Winter, 1992) online version

- Reiss, Oscar. Medicine in Colonial America (2000)

- Reiss, Oscar. Medicine and the American Revolution: How Diseases and Their Treatments Affected the Colonial Army (McFarland, 1998)

- Rosenberg, Charles E. The Cholera Years: The United States in 1832, 1849, and 1866. (2nd ed 1987)

- Rosenberg, Charles E. The Care of Strangers: The Rise of America's Hospital System (1987)

- Rosenkrantz, Barbara G. Public Health and the State: Changing Views in Massachusetts, 1842–1936 (1972).

- Rosner, David A Once Charitable Enterprise: Hospitals and Health Care in Brooklyn and New York 1885-1915 (1982).

- Shryock, Richard H. "Eighteenth Century Medicine in America," Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society (Oct 1949) 59#2 pp 275–292. online

- Smith, Daniel B. "Mortality and Family in the Chesapeake," Journal of Interdisciplinary History 8 (1978): 403 – 427.

- Tannenbaum, Rebecca Jo. Health and Wellness in Colonial America (ABC-CLIO, 2012)

- Viets, Henry R., "Some Features of the History of Medicine in Massachusetts during the Colonial Period, 1620-1770," Isis (1935), 23:389-405

- Vogel. Morris J. The Invention of the Modern Hospital: Boston, 1870-1930 (1980)

- Young. James Harvey. "American Medical Quackery in the Age of the Common Man." The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, (1961) 47#4 pp. 579–593 in JSTOR

Civil War era

- Adams, George Worthington. Doctors in Blue: The Medical History of the Union Army in the Civil War. (1952)

- Bell, Andrew McIlwaine. Mosquito Soldiers: Malaria, Yellow Fever, and the Course of the Civil War. (2010)

- Cunningham, H. H. Doctors in Gray: The Confederate Medical Service. (1958) online edition

- Flannery, Michael A. Civil War Pharmacy: A History of Drugs, Drug Supply and Provision, and Therapeutics for the Union and Confederacy. (London: Pharmaceutical Press, 2004)

- Freemon, Frank R. Gangrene and Glory: Medical Care during the American Civil War. (1998)

- Green, Carol C. Chimborazo: The Confederacy's Largest Hospital. (2004)

- Grzyb, Frank L. Rhode Island's Civil War Hospital: Life and Death at Portsmouth Grove, 1862–1865. (2012)

- Humphreys, Margaret. Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the American Civil War (Johns Hopkins University Press; 2013) 400 pages; argues that care early in the conflict was better than has been portrayed.

- Lande, R. Gregory. Madness, Malingering, and Malfeasance: The Transformation of Psychiatry and the Law in the Civil War Era. (2003).

- Robertson, James I (ed). The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Broadfoot Publishing Co, 1990-1992 reprint (7 volumes); primary sources

- Rutkow, Ira M. Bleeding Blue and Gray: Civil War Surgery and the Evolution of American Medicine. (2005)

- Schmidt, James M. and Guy R. Hasegawa, eds. Years of Change and Suffering: Modern Perspectives on Civil War Medicine. (2009).

- Schroeder–Lein, Glenna R. The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine (2012)

- Schultz, Jane E. Women at the Front: Hospital Workers in Civil War America. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Since 1910

- Brown, E. Richard. Rockefeller Medicine Men: Medicine and Capitalism in America (1979).

- Harvey, A. McGehee. Science at the Bedside: Clinical Research in American Medicine, 1905-1945 (1981).

- Liebenau, Jonathan. Medical Science and Medical Industry: The Formation of the American Pharmaceutical Industry (1987)

- Ludmerer, Kenneth M. Time to Heal: American Medical Education from the Turn of the Century to the Era of Managed Care. (1999) online edition

- Maulitz, Russell C., and Diana E. Long, eds. Grand Rounds: One Hundred Years of Internal Medicine (1988)

- Rothstein, William G. American Medical Schools and the Practice of Medicine (1987)

- Starr, Paul. The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The Rise of a Sovereign Profession and the Making of a Vast Industry (1982)

- Stevens, Rosemary. American Medicine and the Public Interest (1971) covers 1900-1970

- Stevens, Rosemary et al. eds. History and Health Policy in the United States: Putting the Past Back In (Rutgers University Press, 2006) online

Primary sources

- Warner, John Harley, and Janet A. Tighe, eds. Major Problems in the History of American Medicine and Public Health (2006), 560pp; readings in primary and secondary sources excerpt and text search

Historiography

- Bickel, Marcel H. "Thomas N Bonner (1923–2003), medical historian." Journal of Medical Biography (2016) 24#2 pp 183–190.

- Burnham, John C. What Is Medical History? (2005) 163pp. excerpt

- Chaplin, Simon. "Why Creating a Digital Library for the History of Medicine is Harder than You'd Think!." Medical history 60#1 (2016): 126–129. online

- Litoff, Judy Barrett. "Midwives and History." In Rima D. Apple, ed., The History of Women, Health, and Medicine in America: An Encyclopedic Handbook (Garland Publishing, 1990)

- Numbers, Ronald L. "The History of American Medicine: A Field in Ferment" Reviews in American History 10#4 (1982) 245-263 in JSTOR

- Shryock, Richard H. "The Significance of Medicine in American History." The American Historical Review, 62#1 (1956), pp. 81–91 in JSTOR

Major research collections

- The Joseph Meredith Toner Collection at the Library of Congress

- The Center for the History of Medicine at the Harvard Medical School's Countway Library of Medicine

- The Medical Historical Library at Yale University

- The Library of the Institute of the History of Medicine at the Johns Hopkins University

- The Clendening History of Medicine Library at the University of Kansas Medical Center

- The History of Medicine Division of the National Library of Medicine

- The Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia

- The Ruth Lilly Medical Library of the Indiana University (with collections on the practice of medicine in 19th century Indiana and other Midwestern states)