HMS Lion (1910)

Lion underway

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Lion |

| Namesake | Lion |

| Ordered | 1909–1910 Building Programme |

| Builder | HM Dockyard, Devonport |

| Laid down | 29 November 1909 |

| Launched | 6 August 1910 |

| Commissioned | 4 June 1912 |

| Decommissioned | 30 May 1922 |

| Fate | Sold for scrap, 31 January 1924 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type | Lion-class battlecruiser |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 700 ft (213.4 m) |

| Beam | 88 ft 7 in (27 m) |

| Draught | 32 ft 5 in (9.9 m) at deep load |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4 × shafts; 2 × steam turbine sets |

| Speed | 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph) |

| Range | 5,610 nmi (10,390 km; 6,460 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 1,092 |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | |

HMS Lion was a battlecruiser built for the Royal Navy in the 1910s. She was the lead ship of her class, which were nicknamed the "Splendid Cats".[1] They were significant improvements over their predecessors of the Indefatigable class in terms of speed, armament and armour. This was in response to the first German battlecruisers, the Moltke class, which were very much larger and more powerful than the first British battlecruisers, the Invincible class.

Lion served as the flagship of the Grand Fleet's battlecruisers throughout World War I, except when she was being refitted or under repair.[2] She sank the German light cruiser Cöln during the Battle of Heligoland Bight and served as Vice-Admiral David Beatty's flagship at the Battles of Dogger Bank and Jutland. She was so badly damaged at the first of these battles that she had to be towed back to port and was under repair for more than two months. During the Battle of Jutland she suffered a serious propellant fire that could have destroyed the ship had it not been for the bravery of Royal Marine Major Francis Harvey, the gun turret commander, who posthumously received the Victoria Cross for having ordered the magazine flooded. The fire destroyed one gun turret which had to be removed for rebuilding while she was under repair for several months. She spent the rest of the war on uneventful patrols in the North Sea, although she did provide distant cover during the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight in 1917. She was put into reserve in 1920 and sold for scrap in 1924 under the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty.

Design

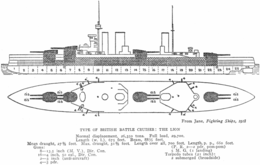

The Lion-class battlecruisers were designed to be as superior to the new German battlecruisers of the Moltke class as the German ships were to the Invincible class. The increase in speed, armour and gun size forced a 65 per cent increase in size over the Indefatigable class.[3] Lion had an overall length of 700 feet (210 m), a beam of 88 feet 7 inches (27 m), and a draught of 32 feet 5 inches (9.88 m) at deep load. The ship displaced 26,270 long tons (26,692 t) at normal load and 30,820 long tons (31,315 t) at deep load.[4]

Propulsion

Lion had two paired sets of Parsons direct-drive steam turbines, each driving two propeller shafts using steam provided by 42 Yarrow boilers. The turbines were designed to produce a total of 70,000 shaft horsepower (52,199 kW), but achieved more than 76,000 shp (56,673 kW) during her trials, although she did not exceed her designed speed of 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph). She carried 3,500 long tons (3,600 t) of coal, and an additional 1,135 long tons (1,153 t) of fuel oil that was sprayed on the coal to increase its burn rate.[5] At full capacity, she could steam for 5,610 nautical miles (10,390 km; 6,460 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[1]

Armament

Lion mounted eight BL 13.5-inch (343 mm) Mk V guns in four twin-gun turrets, designated 'A', 'B', 'Q' and 'X' from front to rear. Her secondary armament consisted of sixteen BL 4-inch (102 mm) Mark VII guns, most of which were mounted in casemates.[6] The two guns mounted above the forward group of casemates were given gun shields during 1913–1914 to better protect the gun crews from weather and enemy action. The starboard forward group of 4-inch guns was removed after April 1917.[7]

She was built without anti-aircraft (AA) guns, but a single quick-firing (QF) 6-pounder (57 mm) Hotchkiss gun on a high-angle mounting was fitted from October 1914 to July 1915.[6] A single QF 3-inch (76 mm) AA gun was added in January 1915, and another the following July. Two 21-inch (533 mm) submerged torpedo tubes were fitted, one on each broadside;[1] fourteen torpedoes were carried.[6]

Armour

The armour protection given to the Lions was heavier than that of the Indefatigables; their waterline belt of Krupp armour measured 9 inches (229 mm) thick amidships. It thinned to 4 inches towards the ships' ends, but did not reach either the bow or the stern. The upper armour belt had a maximum thickness of 6 inches (152 mm) over the same length as the thickest part of the waterline armour and thinned to 5 inches (127 mm) abreast the end turrets. The gun turrets and barbettes were protected by 8 to 9 inches (203 to 229 mm) of armour, except for the turret roofs which used 2.5 to 3.25 inches (64 to 83 mm). The thickness of the nickel steel deck ranged from 1 to 2.5 inches (25 to 64 mm). Nickel steel torpedo bulkheads 2.5 inches thick were fitted abreast the magazines and shell rooms.[8] After the Battle of Jutland revealed her vulnerability to plunging shellfire, 1 inch (25 mm) of additional armour, weighing approximately 100 long tons (102 t), was added to the magazine crowns and turret roofs.[9]

Wartime modifications

Lion received a fire-control director between mid-1915 and May 1916 that centralised the pointing and firing of the guns under the command of the director positioned on the foremast. The turret crewmen merely had to follow pointers controlled by the director to align their guns on the target. This greatly increased accuracy as it was easier to spot the fall of shells and eliminated the problem of the ship's roll dispersing the shells as each turret fired individually.[10]

By early 1918 Lion carried a Sopwith Pup and a Sopwith 1½ Strutter on flying-off platforms fitted on top of 'Q' and 'X' turrets. Each platform had a canvas hangar to protect the aircraft during inclement weather.[11]

Construction and career

Lion was laid down at the Devonport Dockyard, Plymouth, on 29 November 1909. She was launched on 6 August 1910 and was commissioned on 4 June 1912.[12] Upon commissioning, Lion became the flagship of the 1st Cruiser Squadron, which was renamed the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron (BCS) in January 1913. Rear Admiral Beatty assumed command of the 1st BCS on 1 March 1913. Lion, along with the rest of the 1st BCS, made a port visit to Brest in February 1914 and the squadron visited Russia in June,[13] where Lion's officers entertained the Russian imperial family aboard while in Kronstadt.[14]

World War I

Battle of Heligoland Bight

Lion's first action was as flagship of the battlecruiser force under the command of Admiral Beatty during the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28 August 1914. Beatty's ships had originally been intended as distant support of the British cruisers and destroyers closer to the German coast in case the large ships of the High Seas Fleet sortied in response to the British attacks. They turned south at full speed at 11:35[Note 1] when the British light forces failed to disengage on schedule and the rising tide meant that German capital ships would be able to clear the bar at the mouth of the Jade Estuary. The brand-new light cruiser Arethusa had been crippled earlier in the battle and was under fire from the German light cruisers Strassburg and Cöln when Beatty's battlecruisers loomed out of the mist at 12:37. Strassburg was able to duck into the mists and evade fire, but Cöln remained visible and was quickly crippled by fire from the squadron. Beatty, however, was distracted from the task of finishing her off by the sudden appearance of the elderly light cruiser Ariadne directly to his front. He turned in pursuit and reduced her to a flaming hulk in only three salvos at close range–under 6,000 yards (5.5 km). At 13:10 Beatty turned north and made a general signal to retire. Beatty's main body encountered the crippled Cöln shortly after turning north and she was sunk by two salvos from Lion.[15]

Raid on Scarborough

The German Navy had decided on a strategy of bombarding British towns on the North Sea coast to draw out the Royal Navy and destroy elements of it in detail. An earlier Raid on Yarmouth on 3 November had been partially successful, but a larger-scale operation was devised by Admiral Franz von Hipper afterwards. The fast battlecruisers would actually conduct the bombardment while the entire High Seas Fleet was to station itself east of Dogger Bank to provide cover for their return and to destroy any elements of the Royal Navy that responded to the raid. But what the Germans did not know was that the British were reading the German naval codes and were planning to catch the raiding force on its return journey, although they were not aware that the High Seas Fleet would be at sea as well. Admiral Beatty's 1st BCS, now reduced to four ships, including Lion, as well as Vice-Admiral Sir George Warrender's 2nd Battle Squadron with six dreadnoughts, was detached from the Grand Fleet in an attempt to intercept the Germans near Dogger Bank.[16]

Admiral Hipper set sail on 15 December 1914 for another such raid and successfully bombarded several English towns, but British destroyers escorting the 1st BCS had already encountered German destroyers of the High Seas Fleet at 05:15 and fought an inconclusive action with them. Warrender had received a signal at 05:40 that the destroyer Lynx was engaging enemy destroyers although Beatty had not. The destroyer Shark spotted the German armoured cruiser Roon and her escorts at about 07:00, but could not transmit the message until 07:25. Admiral Warrender received the signal, as did the battlecruiser New Zealand, but Beatty did not, despite the fact that New Zealand had been specifically tasked to relay messages between the destroyers and Beatty. Warrender attempted to pass on Shark's message to Beatty at 07:36, but did not manage to make contact until 07:55. Beatty reversed course when he got the message and dispatched New Zealand to search for Roon. She was being overhauled by New Zealand when Beatty received messages that Scarborough was being shelled at 09:00. Beatty ordered New Zealand to rejoin the squadron and turned west for Scarborough.[17]

The British forces split going around the shallow Southwest Patch of the Dogger Bank; Beatty's ships passed to the north while Warrender passed to the south as they headed west to block the main route through the minefields defending the English coast. This left a 15-nautical-mile (28 km) gap between them through which the German light forces began to move. At 12:25, the light cruisers of the II Scouting Group began to pass the British forces searching for Hipper. The light cruiser Southampton spotted the light cruiser Stralsund and signalled a report to Beatty. At 12:30 Beatty turned his battlecruisers towards the German ships. Beatty presumed that the German cruisers were the advance screen for Hipper's ships, however, those were some 50 km (31 mi) behind. The 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron, which had been screening for Beatty's ships, detached to pursue the German cruisers, but a misinterpreted signal from the British battlecruisers sent them back to their screening positions.[Note 2] This confusion allowed the German light cruisers to escape, and alerted Hipper to the location of the British battlecruisers. The German battlecruisers wheeled to the northeast of the British forces and made good their escape.[18]

Battle of Dogger Bank

On 23 January 1915, a force of German battlecruisers under the command of Admiral Franz von Hipper sortied to clear the Dogger Bank of any British fishing boats or small craft that might be there to collect intelligence on German movements. However, the British were reading their coded messages and sailed to intercept them with a larger force of British battlecruisers under the command of Admiral Beatty. Contact was initiated at 07:20 on the 24th when the British light cruiser Arethusa spotted the German light cruiser SMS Kolberg. By 07:35 the Germans had spotted Beatty's force and Hipper ordered a turn to the south at 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph), believing that this would suffice if the ships that he saw to his north-west were British battleships and that he could always increase speed to Blücher's maximum speed of 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph) if they were British battlecruisers.[19]

Beatty ordered his battlecruisers to make all practicable speed to catch the Germans before they could escape. The leading ships, Lion, her sister Princess Royal and Tiger, were doing 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph) in pursuit and Lion opened fire at 08:52 at a range of 20,000 yards (18,000 m). The other ships followed a few minutes later but, hampered by the extreme range and decreasing visibility, they did not score their first hit on Blücher until 09:09. The German battlecruisers opened fire themselves a few minutes later at 09:11, at a range of 18,000 yards (16,000 m), and concentrated their fire on Lion. They first hit her at 9:28 on the waterline with a shell that flooded a coal bunker. Shortly afterwards a 21-centimetre (8.3 in) shell from Blücher hit the roof of 'A' turret, denting it and knocking out the left gun for two hours. At 09:35 Beatty signalled 'Engage the corresponding ships in the enemy's line', but Tiger's captain, believing that Indomitable was already engaging Blücher, fired at Seydlitz, as did Lion, which left Moltke unengaged and able to continue to engage Lion without risk. However, Lion scored the first serious hit of the battle when one of her shells penetrated the working chamber of Seydlitz's rear barbette at 09:40 and ignited the propellant lying exposed. The resulting fire spread into the other turret and burnt out both of them, killing 159 men.[20] Seydlitz returned the damage at 10:01 with a 283-millimetre (11.1 in) shell that ricocheted off the water and pierced Lion's five-inch armour aft, although it failed to explode. However, the resulting 24-by-18-inch (610 by 460 mm) hole flooded the low power switchboard compartment and eventually shorted out two of Lion's three dynamos.[2] Derfflinger scored the most telling hits on Lion at 10:18 when two 305-millimetre (12 in) shells struck her port side below the waterline. The shock was so great that her captain, Ernle Chatfield, thought that she had been torpedoed.[21] One shell pierced the five-inch armour forward and burst in a wing compartment behind the armour. It drove in a 30-by-24-inch (760 by 610 mm) piece of armour and flooded several compartments adjacent to the torpedo flat and the torpedo body room. One splinter put a hole in the exhaust pipe of the capstan engine which eventually contaminated the auxiliary condenser with saltwater. The other shell hit further aft and burst on the six-inch portion of the waterline belt. It drove in two armour plates about 2 feet (0.61 m) and flooded some of the lower coal bunkers.[22] At 10:41[23] a 283 mm shell burst against the eight-inch armour of 'A' barbette, but only started a small fire in the 'A' turret lobby that was quickly put out, although the magazine was partially flooded when a false report was received that it was on fire as well. Soon afterwards Lion was hit by a number of shells in quick succession, but only one of these was serious. A shell burst on the nine-inch armour belt abreast the engine room and drove a 16-by-5.75-foot (4.88 by 1.75 m) armour plate about two feet inboard and ruptured the port engine's feedwater tank.[24] By 10:52 Lion had been hit fourteen times and had taken aboard some 3,000 long tons (3,000 t) of water which gave her a list of 10° to port and reduced her speed. Shortly afterwards her port engine broke down and her speed dropped to 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph).[23]

In the meantime Blücher had been heavily damaged by fire from all the other battlecruisers; her speed had dropped to 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) and her steering gear had been jammed. Beatty ordered Indomitable to attack her at 10:48. Six minutes later Beatty spotted what he thought was a submarine periscope on the starboard bow and ordered an immediate 90° turn to port to avoid the submarine, although he failed to hoist the 'Submarine Warning' flag because most of Lion's signal halyards had been shot away. Almost immediately afterwards Lion lost her remaining dynamo to the rising water which knocked out all remaining light and power. He ordered 'Course Northeast' at 11:02 to bring his ships back to their pursuit of Hipper. He also hoisted 'Attack the rear of the enemy' on the other halyard although there was no connection between the two signals. This caused Rear-Admiral Sir Gordon Moore, temporarily commanding in New Zealand, to think that the signals meant to attack Blücher, which was about 8,000 yards (7,300 m) to the northeast, so they turned away from the pursuit of Hipper's main body and engaged Blücher. Beatty tried to correct the mistake, but he was so far behind the leading battlecruisers that his signals could not be read amidst the smoke and haze.[25]

Lion's starboard engine was temporarily shut down due to contaminated feed water, but it was restarted and Lion headed home at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) when the rest of the battlecruisers caught up with her around 12:45. At 14:30 the starboard engine began to fail and her speed was reduced to 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph). Indomitable was ordered to tow Lion back to port at 15:00, but it took two hours and two tries before she could start to tow Lion, and a further day-and-a-half to reach port at speeds of 7–10 knots (13–19 km/h; 8.1–11.5 mph), even after Lion's starboard engine was temporarily repaired.[26]

Lion was temporarily repaired at Rosyth with timber and concrete before sailing to Newcastle upon Tyne to be repaired by Palmers; the Admiralty did not wish it known that she was damaged badly enough to require repair at either Portsmouth or Devonport Dockyards lest that be seen as a sign of defeat. She was heeled 8° to starboard with four cofferdams in place between 9 February and 28 March to repair about 1,500 square feet (140 m2) of bottom plating and replace five armour plates and their supporting structure.[24] She rejoined the Battlecruiser Fleet, again as Beatty's flagship, on 7 April.[27] She had fired 243 rounds from her main guns, but had only made four hits: one each on Blücher and Derfflinger, and two on Seydlitz. In return she had been hit by the Germans sixteen times, but only suffered one man killed and twenty wounded.[22]

Battle of Jutland

On 31 May 1916 Lion was the flagship of Admiral Beatty's Battlecruiser Fleet which had put to sea to intercept a sortie by the High Seas Fleet into the North Sea. The British were able to decode the German radio messages and left their bases before the Germans put to sea. Hipper's battlecruisers spotted the Battlecruiser Fleet to their west at 15:20, but Beatty's ships did not spot the Germans to their east until ten minutes later. Almost immediately afterwards, at 15:32, he ordered a course change to east-south-east to position himself astride the Germans' line of retreat and called his ships' crews to action stations. Hipper ordered his ships to turn to starboard, away from the British, to assume a south-easterly course, and reduced speed to 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) to allow three light cruisers of the 2nd Scouting Group to catch up. With this turn Hipper was falling back on the High Seas Fleet, then about 60 miles (97 km) behind him. Around this time Beatty altered course to the east as it was quickly apparent that he was still too far north to cut off Hipper.[28]

This began what was to be called the 'Run to the South' as Beatty changed course to steer east-south-east at 15:45, paralleling Hipper's course, now that the range closed to under 18,000 yards (16,000 m). The Germans opened fire first at 15:48, followed almost immediately afterwards by the British. The British ships were still in the process of making their turn as only the two leading ships, Lion and Princess Royal, had steadied on their course when the Germans opened fire. The German fire was accurate from the beginning, but the British overestimated the range as the German ships blended into the haze. Lion, as the leading British ship, engaged Lützow, her opposite number in the German formation. Lützow's fire was very accurate, and Lion was hit twice within three minutes of the Germans' opening fire. By 15:54 the range was down to 12,900 yards (11,800 m), and Beatty ordered a course change two points to starboard to open up the range at 15:57.[29] Lion scored her first hit on Lützow two minutes later, but Lützow returned the favour at 16:00 when one of her 305 mm shells hit 'Q' turret at a range of 16,500 yards (15,100 m).[30] The shell penetrated the joint between the nine-inch turret faceplate and the 3.5-inch roof and detonated over the centre of the left-hand gun. It blew the front roof plate and the centre faceplate off the turret, killed or wounded everyone in the turret, and started a fire that smouldered, despite efforts to put it out that had been thought to have been successful. Accounts of subsequent events differ, but the magazine doors had been closed and the magazine flooded when the smouldering fire ignited the eight full propellant charges in the turret working room at 16:28. They burned violently, with the flames reaching as high as the masthead, and killed most of the magazine and shell room crews still in the lower part of the mounting. The gas pressure severely buckled the magazine doors, and the magazine would probably have exploded if it had not already been flooded.[31] Royal Marine Major Francis Harvey, the mortally wounded turret commander, was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for having ordered the magazine flooded.[32]

At 16:11 Lion observed the track of a torpedo fired by Moltke pass astern, but it was thought that the torpedo was fired by a U-boat on the disengaged side. This was confirmed when the destroyer Landrail reported having spotted a periscope before the torpedo tracks were seen.[33] The range had grown too far for accurate shooting so Beatty altered course four points to port to close the range again between 16:12 and 16:15. This resulted in Lion hitting Lützow again at 16:14, but Lützow hit Lion several times in return shortly afterwards. The smoke and haze from these hits caused Lützow to lose sight of Lion, and she switched her fire to Queen Mary at 16:16. By 16:25 the range was down to 14,400 yards (13,200 m), and Beatty turned two points to starboard to open the range again. However, it was too late for Queen Mary, which was hit multiple times in quick succession about that time, and her forward magazines exploded.[34] At 16:30 the light cruiser Southampton, scouting in front of Beatty's ships, spotted the lead elements of the High Seas Fleet charging north at top speed. Three minutes later she sighted the topmasts of Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer's battleships, but did not transmit a message to Beatty for another five minutes. Beatty continued south for another two minutes to confirm the sighting himself before ordering a sixteen-point turn to starboard in succession.[35]

Lion was hit twice more, during what came to be called the 'Run to the North', after the German battlecruisers made their own turn north.[36] Beatty's ships maintained full speed to try to put some separation between them and the High Seas Fleet and gradually moved out of range. They turned north and then northeast to try to rendezvous with the main body of the Grand Fleet. At 17:40 they opened fire again on the German battlecruisers. The setting sun blinded the German gunners, and they could not make out the British ships and turned away to the northeast at 17:47.[37] Beatty gradually turned more towards the east to allow him to cover the deployment of the Grand Fleet into its battle formation and to move ahead of it, but he mistimed his manoeuvre and forced the leading division to fall off towards the east, further away from the Germans. By 18:35 Beatty was following the 3rd BCS as they were steering east-south-east, leading the Grand Fleet, and continuing to engage Hipper's battlecruisers to their southwest. A few minutes earlier Scheer had ordered a simultaneous 180° starboard turn, and Beatty lost sight of them in the haze.[38] At 18:44 Beatty turned his ships southeast and to the south-south-east four minutes later searching for Hipper's ships. Beatty took this opportunity to recall the two surviving ships of the 3rd BCS to take position astern of New Zealand and then slowed down to eighteen knots and altered course to the south to prevent himself from getting separated from the Grand Fleet. At this moment Lion's gyrocompass failed, and she made a complete circle before her steering was brought under control again.[39] At 18:55 Scheer ordered another 180° turn, which put them on a converging course again with the Grand Fleet, which had altered course itself to the south. This allowed the Grand Fleet to cross Scheer's T, and they badly damaged his leading ships. Scheer ordered yet another 180° turn at 19:13 in an attempt to extricate the High Seas Fleet from the trap into which he had sent them.[40]

This manoeuvre was successful, and the British lost sight of the Germans until 20:05, when the light cruiser Castor spotted smoke bearing west-north-west. Ten minutes later she had closed the range enough to identify German torpedo boats and had engaged them. Beatty turned west upon hearing the sounds of gunfire and spotted the German battlecruisers only 8,500 yards (7,800 m) away. Inflexible opened fire at 20:20, followed almost immediately by the rest of Beatty's battlecruisers.[41] Shortly after 20:30 the pre-dreadnought battleships of Rear Admiral Mauve's II Battle Squadron were spotted and fire switched to them. The Germans were able to fire only a few rounds at them because of the poor visibility and turned away to the west. The British battlecruisers hit the German ships several times before they blended into the haze around 20:40.[42] After this Beatty changed course to south-southeast and maintained that course, ahead of both the Grand Fleet and the High Seas Fleet, until 02:55 the next morning when the order was given to reverse course.[43]

Lion and the rest of the battlecruisers reached Rosyth on the morning of 2 June 1916[44] where she began repairs that lasted until 19 July. The remains of 'Q' turret were removed during this period and not replaced until later. She had been hit a total of fourteen times and suffered 99 dead and 51 wounded during the battle. She fired 326 rounds from her main guns, but can only be credited with four hits on Lützow and one on Derfflinger. She also fired seven torpedoes, four at the German battleships, two at Derfflinger and one at the light cruiser Wiesbaden without success.[45]

Post-Jutland career

She rejoined the Battlecruiser Fleet, again as Beatty's flagship, on 19 July 1916 without 'Q' turret, but then had the turret replaced during a visit to Armstrong Whitworth at Elswick that lasted from 6 to 23 September. In the meantime, on the evening of 18 August the Grand Fleet put to sea in response to a message deciphered by Room 40 which indicated that the High Seas Fleet, less the II Squadron, would be leaving harbour that night. The German objective was to bombard Sunderland on the 19th, with extensive reconnaissance provided by airships and submarines. The Grand Fleet sailed with 29 dreadnought battleships and six battlecruisers.[Note 3] Throughout the 19th, Jellicoe and Scheer received conflicting intelligence, with the result that having reached its rendezvous in the North Sea, the Grand Fleet steered north in the erroneous belief that it had entered a minefield before turning south again. Scheer steered south-eastward pursuing a lone British battle squadron reported by an airship, which was in fact the Harwich Force under Commodore Tyrwhitt. Having realised their mistake the Germans then shaped course for home. The only contact came in the evening when Tyrwhitt sighted the High Seas Fleet but was unable to achieve an advantageous attack position before dark, and broke off contact. Both the British and the German fleets returned home, the British having lost two cruisers to submarine attacks and the Germans having a dreadnought damaged by torpedo.[46]

Lion became the flagship of Vice-Admiral W. C. Pakenham in December 1916 when he assumed command of the Battlecruiser Fleet upon Beatty's promotion to command of the Grand Fleet.[27] Lion had an uneventful time for the rest of the war, conducting patrols of the North Sea as the High Seas Fleet was forbidden to risk any more losses. She provided support for British light forces involved in the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight on 17 November 1917, but never came within range of any German forces. The 1st BCS, including Lion, sailed on 12 December in a futile attempt to intercept the German destroyers that had sunk the convoy en route to Norway earlier that day, but returned to base the following day.[47] Lion, along with the rest of the Grand Fleet, sortied on the afternoon of 23 March 1918 after radio transmissions had revealed that the High Seas Fleet was at sea after a failed attempt to intercept the regular British convoy to Norway. However, the Germans were too far ahead of the British and escaped without firing a shot.[48] When the High Seas Fleet sailed for Scapa Flow on 21 November 1918 to be interned, she was among the escorting ships. Along with the rest of the 1st BCS she guarded the interned ships[49] until she was assigned to the Atlantic Fleet in April 1919 and then placed in reserve in March 1920. Paid off on 30 March 1922, despite a press campaign to have her saved for the nation as a memorial, Lion was sold for scrap on 31 January 1924 for £77,000[50] to meet the tonnage limitations of the Washington Naval Treaty.[1]

Notes

- ^ The times used in this article are in UT, which is one hour behind the time zone now known as CET, which is often used in German works.

- ^ Beatty had intended on retaining only the two rearmost light cruisers from Goodenough's squadron; however, Nottingham's signalman misinterpreted the signal, thinking that it was intended for the whole squadron, and thus transmitted it to Goodenough, who ordered his ships back into their screening positions ahead of Beatty's battlecruisers.[citation needed]

- ^ While no sources explicitly state that Lion was part of the fleet at this time, of the seven Royal Navy battlecruisers then in commission, Indomitable was under refit through August and the only one unavailable for action. See Roberts, p. 122.

References

- ^ a b c d Preston, p. 29

- ^ a b Campbell, p. 29

- ^ Burt, pp. 172, 176

- ^ Roberts, pp. 43–44

- ^ Roberts, pp. 70–76, 80

- ^ a b c Roberts, p. 83

- ^ Burt, p. 179

- ^ Roberts, pp. 109, 112

- ^ Roberts, p. 113

- ^ Roberts, pp. 92–93

- ^ Roberts, p. 92

- ^ Roberts, p. 41

- ^ Burt, p. 180

- ^ "HMS Lion". MaritimeQuest. 22 February 2007. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ Massie, pp. 109–113

- ^ Massie, pp. 333–334

- ^ Massie, pp. 342–343

- ^ Tarrant, p. 34

- ^ Massie, pp. 376–384

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 35–36

- ^ Massie, p. 396

- ^ a b Campbell, pp. 29–30

- ^ a b Massie, p. 397

- ^ a b Campbell, p. 30

- ^ Massie, pp. 398–402

- ^ Massie, pp. 409–412

- ^ a b Roberts, p. 123

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 69, 71, 75

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 80–83

- ^ Massie, p. 592

- ^ Roberts, p. 116

- ^ "No. 29751". The London Gazette (Supplement). 15 September 1916. p. 9067.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 85

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 89–91

- ^ Massie, pp. 598–600

- ^ Massie, p. 601

- ^ Tarrant, p. 109

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 130–138

- ^ Tarrant, p. 145

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 149, 157

- ^ Tarrant, p. 175

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 177–178

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 178, 224

- ^ Massie, p. 657

- ^ Campbell, pp. 30, 32

- ^ Marder, III, pp. 287–296

- ^ Newbolt, pp. 169, 193

- ^ Massie, p. 748

- ^ Marder, V, p. 273

- ^ Burt, p. 183

Bibliography

- Brown, David K. (1999). The Grand Fleet: Warship Design and Development 1906–1922. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-315-X.

- Burt, R. A. (2012). British Battleships of World War One (Revised ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-053-5.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1978). Battle Cruisers. Warship Special. Vol. 1. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-130-0.

- Marder, Arthur J. (1978). From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow, The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 1904–1919. Vol. III: Jutland and After, May 1916 – December 1916 (Second ed.). London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-215841-4.

- Marder, Arthur J. (1970). From Dreadnought to Scapa Flow: The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 1904–1919. Vol. V: Victory and Aftermath (January 1918 – June 1919). London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-215187-8.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-45671-6.

- Newbolt, Henry (1996) [1931]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents. Vol. V. Nashville, Tennessee: Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-255-1.

- Preston, Antony (1985). "Great Britain and Empire Forces". In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 1–104. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Roberts, John (1997). Battlecruisers. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-068-1.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-917-8.

External links

- Account of the battle of Jutland by Alexander Grant, a gunner aboard Lion

- Maritimequest HMS Lion Photo Gallery

- Battle of Jutland Crew Lists Project – HMS Lion Crew List